“Paul Simon called Stax and said, ‘Who are those Jamaican musicians?’ They told him, ‘Those are some white boys from Alabama!’” David Hood on being starstruck by Aretha Franklin, what Otis Redding taught him, and tales from golden age of Muscle Shoals

In this interview from the Bass Player archive, Hood reflects on his career as a ‘Swamper’, playing on hits by Paul Simon, the Staple Singers Aretha Franklin and more

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The “Muscle Shoals sound,” a drum-and-bass-heavy blend of soul, pop, and rock, defined the Golden Age of Southern R&B.

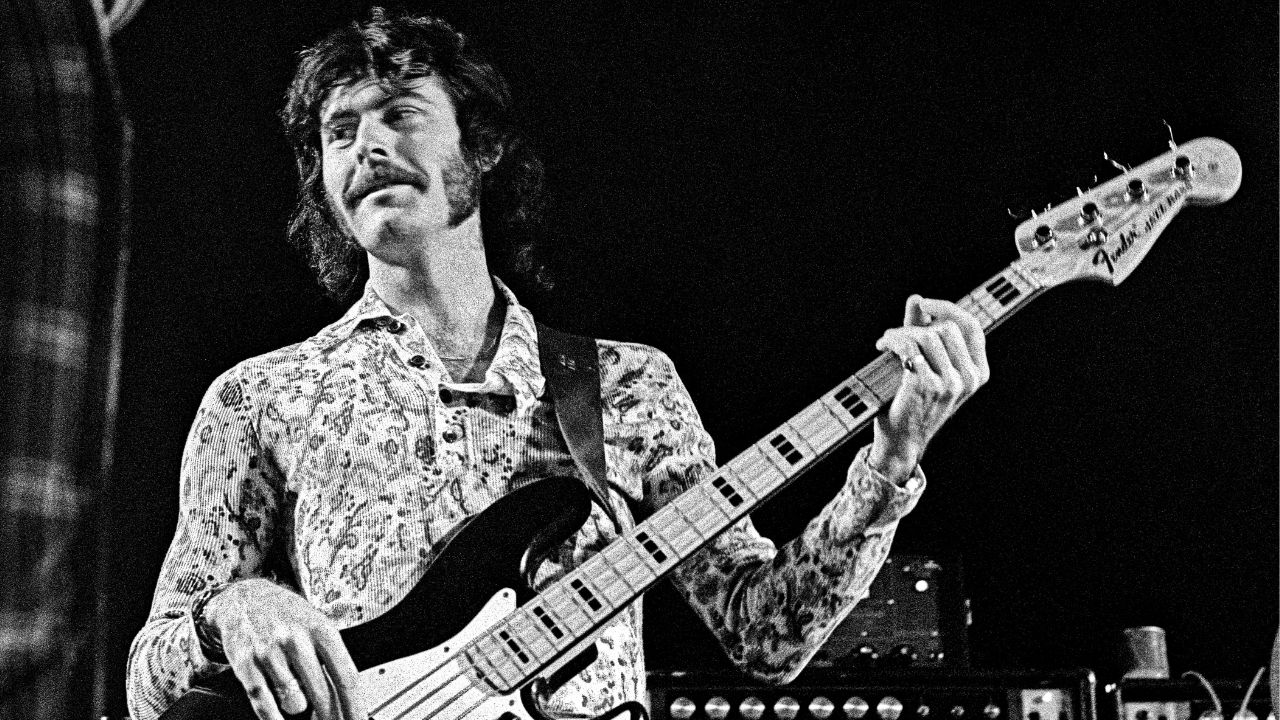

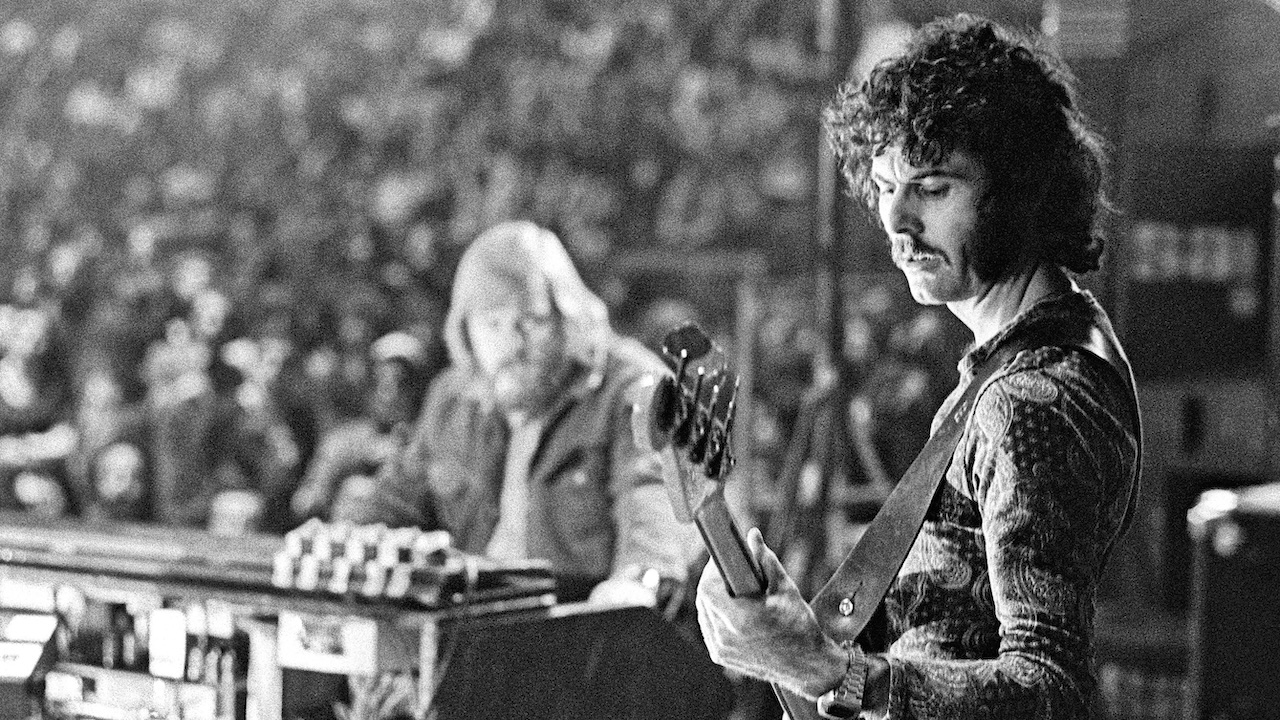

As the creators of that sound, studio strongmen David Hood, drummer Roger Hawkins, and the rest of the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section (nicknamed the Swampers) provided the backbone for a succession of hits from soul acts like Wilson Pickett, and the Staple Singers, as well as groove-loving rockers like Boz Scaggs, Bob Seger, and Jimmy Buffett.

Hood was an Alabama native who mastered the art of delivering more with fewer notes. Throughout the ’60s and ’70s, his Southern-flavored basslines were sought out by legendary artists from Aretha Franklin to Paul Simon to the Rolling Stones, but his singular contribution to the Staple Singers’ I'll Take You There may well be his most famous bassline.

The million-dollar questions for anyone with such an unforgettable body of recorded work is, of course, what was his favourite session?

“I loved all the Staple Singers and Stax stuff,” Hood told Bass Player. “But I’ve been privileged to work with a lot of other great people. There have been some great Atlantic things produced by Jerry Wexler as well as Arif Mardin.”

“I enjoyed working with Phil Ramone, and Tom Dowd, and I got to work with Otis Redding when he was producing. Otis taught me a lot of things about rhythm and feel, like playing on the upbeat when you would normally be playing on the downbeat. His feel was so good, and you can hear it in all of his records – horn lines and everything. You can tell Otis had a hand in that.

“Some of the early Bob Seger stuff was fun, and so was Paul Simon, though he got kind of weird toward the end. He had heard I’ll Take You There, so he called Stax and said, ‘Who are those Jamaican musicians?' They told him, ‘Those are some white boys from Alabama!’

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“When he first came down here he told us, ‘This is the song, I want you all to just do what you do.’ We did and were very successful. But toward the end he figured, ‘Gosh, these guys aren’t musical geniuses or anything – I know more than they do.’ So he started dictating every note, and it didn’t sound as good.”

Do you remember your first session?

Everybody else had been playing longer than me, and I always felt like I was a little behind

“The band I played in booked the session – the lead singer’s father put up the money. We rehearsed the song and just went in and played it. I wasn’t scared or nervous, because I didn’t know I should be. It was only after I started working for other people that I got nervous.

“Everybody else had been playing longer than me, and I always felt like I was a little behind. Back then it was all mono, so if you messed up it was stop and start all over again – there was no punching in.

“That was a bloodbath at first, because Rick Hall was a taskmaster who didn’t mind embarrassing you in front of everybody. That’s when I learned to just cancel my feelings and put everything out of my mind except the job at hand. I loved the job, though – I was learning new things and getting paid. Even though it wasn’t a lot of money, it was better than working at the tire store.”

You played on countless hits in the ’60s and ’70s. How many tracks would you cut in a a typical week?

“Sometimes we would cut 50 tracks in a week. The producer would run in these songwriters, we would record their track, they would leave and finish it, and we would never know what it was. Later on it would come out, and I’d say, ‘Is that us? It sounds familiar.’

“For a while we were a track factory, and we were really good at it. We could make them all sound good and different enough. But it’s hard over the long run. You start to burn out.”

How would you stay focused during a session?

“I don’t have a secret to staying focused; I just have to shut out everything else and go into this state of mind where there’s nothing but the music. When you’re doing that and you lock into a real good thing, it’s almost like you’re floating – your body’s doing it without you having to think about it. That’s a great thing, and I don’t think it happens with rhythm sections that are just thrown together.”

Were any of the sessions particularly challenging?

“I’d hate it when something didn’t work on a session, but I soon learned you can’t force things; if it’s not working one way you just try something else. Usually it helps to simplify. I’m not a real technical player anyway, so I’m more comfortable playing less.

“Having a good sound and playing in tune and in time is much more important than chops. You’re not playing for yourself or for other bass players – you’re playing to make a song come out. It’s not brain surgery. It’s all about entertainment. If you’re not pleasing someone you’re wasting your time.”

Did you and drummer Roger Hawkins have a routine for working out parts?

“Sometimes we work out some little pattern ahead of time, and other times we just start playing and fit together somehow without saying anything. For me that's because I was the last one to come into the scene, and I had to listen to everybody and make sure I was doing the right thing. I had to learn to lock in rather than to lead, because I was the new guy.

“Most of the drummers I've worked with say they like working with me because I don't fight with them. So if I'm working with a good drummer I sound good, and if I'm working with a bad drummer I sound bad.”

Have you been in many sessions where something just doesn't work?

You're not playing for yourself or for other bass players – you're playing to make a song come out. It's not brain surgery. It's all about entertainment

“Yeah, a lot – and I hate it. It's your whole soul on the line. Plus, after all these years I have a reputation to live up to. But I've learned you can't force things; if it's not working one way you just try something else. Usually it helps to simplify. I'm not a real technical player, anyway, so I'm more comfortable playing less.”

“Having a good sound and playing in tune and in time is much more important than chops. You're not playing for yourself or for other bass players – you're playing to make a song come out. It's not brain surgery. It's all about entertainment. If you're not pleasing someone you're wasting your time.”

“Don't get me wrong, though – I love for somebody to give me a challenging line. Even if I don't nail it exactly, it's fun to do my version of it. I get tired of sessions where nobody has any suggestions; that's not any fun. I know what / know, so it's fun to get outside ideas.”

Were you ever starstruck by an artist?

“In the beginning I was starstruck by artists, and Aretha Franklin was one of them. I had a Columbia record called Trouble in Mind that I thought was wonderful.

“On those first sessions I played trombone, but later I got to play bass with her, and that was fun. She’s such a great vocalist and piano player that you can just pattern your part after what she’s doing.”

Nick Wells was the Editor of Bass Guitar magazine from 2009 to 2011, before making strides into the world of Artist Relations with Sheldon Dingwall and Dingwall Guitars. He's also the producer of bass-centric documentaries, Walking the Changes and Beneath the Bassline, as well as Production Manager and Artist Liaison for ScottsBassLessons. In his free time, you'll find him jumping around his bedroom to Kool & The Gang while hammering the life out of his P-Bass.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.