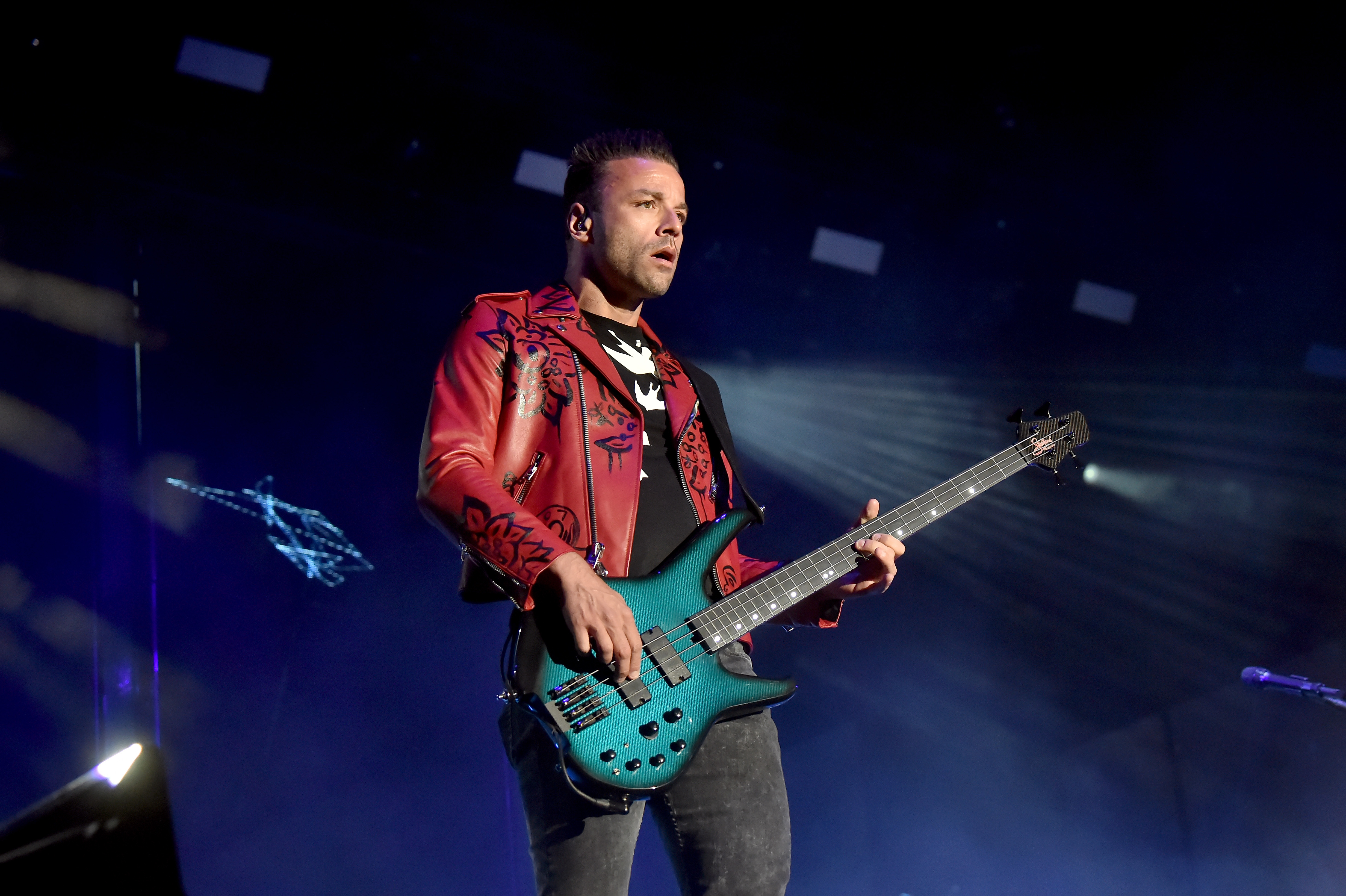

Too much is never enough: Muse’s Chris Wolstenholme reinvents art-rock bass for the 21st century

Muse's bass master on The Resistance, riffs and how he gets his tone

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A well-worn cliché about the Brits is that they're serious, understated, subtle, and—heavens, no—certainly not silly or anything like that. Well, Muse’s Chris Wolstenholme is having none of it, musically or otherwise. “There’s always been this thing with English bands where it’s a bit shoe-gaze-y, you know what I mean? British bands find it hard to just let loose and rock out sometimes. Back in the ’70s, British bands were great; they had a certain over-the-top-ness. It’s almost like bands are scared to do stuff like that now.” Not so for the members of Muse: “We just think, Fuck it, you know?”

“Over-the-top-ness” is a good way to describe the bombastic blend of decade-associated styles brought to bear on Muse’s fifth studio album, The Resistance [Warner Bros.]. From the ’70s, Muse unabashedly draws on operatic, classically influenced art-rock bands for epic tunes like “Eurasia”; the bass-synth-inspired, totally ’80s new wave groove in “Uprising” sounds like a cross between Gary Glitter and Gary Numan; and it’s all powered by the hard-rock rhythm sections of Wolstenholme’s coming-of-age decade, the grungy ’90s. Try to imagine mashing up Queen, Depeche Mode, and Rage Against The Machine, and you can understand why Chris has taken the attitude he has. “Sometimes,” says the 30- year-old, “it’s good to be silly.”

Guitarist/lead singer Matt Bellamy, drummer Dominic Howard, and Wolstenholme have been working on sound—both individually and as a group—for 15 years. Instead of merely taking up space, Wolstenholme has always had to take up the right kind of space to match Bellamy’s sonic and melodic choices. The result of his life’s work is a multi-layered, righteously distorted panoply of bass tone (with a signal path for the ages) that not only anchors Muse as a band, but perhaps is a new standard for sonic creativity in rock bass.

Muse is certainly a long way from the tiny town of Teignmouth in Devon, England, where Chris first met Matt and Dom in their early teens. Wolstenholme had been playing guitar and drums with a different group when they invited him to join their cover band. “I’d not really played bass before. So I said I’d go along for a couple of rehearsals and see how it went. But then once I started playing bass, I really enjoyed it, and I felt more comfortable than I did on the other instruments. Fast-forward 15 years and they’re rehearsing for a world tour at their own custombuilt studio in northern Italy, where The Resistance was tracked. When they depart they’ll be selling out arenas and opening for U2 in select stadium shows across the U.S. this fall. Not a bad call for a teenager!

The only real band Wolstenholme has ever been in has also served as his music school. Matt, Dom, and Chris essentially taught each other how to play and how to play together. Whether it’s the lack of formal training, or just an innate sense of reckless musical abandon, the irresistible bass lines sprinkled throughout Muse’s catalog are a testament to what’s possible when an interesting bass line and serving the song aren’t mutually exclusive. And while there are certainly some mellower bass moments on the new record—like the three-part “symphony” that closes the album—those familiar with Wolstenholme’s signature sounds and lines will have plenty to process from The Resistance.

In recording The Resistance, what has changed for you as a player since you made Black Holes and Absolution?

In the past, if one of our songs didn’t have a great bass line, I found it hard to enjoy playing it. Now, it doesn’t bother me so much what I’m playing as long as I can enjoy the music as a whole. And I think that’s something that we’ve all learned to appreciate—that it’s not about the individual, or massaging your own ego. It’s about creating music that sounds good when you’re playing together. There are some tracks where the bass lines alone are great to play, and some, like the symphony at the end, that an inexperienced bass player could easily play. And I’m fine with that. Sometimes that’s the stuff that I enjoy playing more now, because I don’t have to worry too much about what I’m playing. I can just lose myself in the music.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

What was the writing process like for this record?

Matt generally comes up with the basics of the song. Sometimes that idea is finished in his head before Dom and I have even heard it. Other ideas he brings to us are very raw—just a chord structure and a melody—and in those environments, we’d get in a room together and just keep playing it over and over again, and wait for some magic to happen. Because sometimes it can just be one tiny little thing that somebody does, and it will influence an entire verse, or an entire chorus, or whatever.

Even though Matt is the songwriter, he’s always been very open to me and Dom having as much influence as possible. And I think he’s been looking for that, because he knows that a chord structure and a melody are not always enough to pull a song off. You need a bit of magic from somebody else. So quite often he’s looking for things like that to come from me and Dom.

How do you choose what kind of fuzz, drive, and edge to use? Do you have templates for choosing sounds?

A lot of it depends on what Matt is doing. You don’t want the guitars and the distortion of the bass to become one. You want them to be separate. And that’s a very hard thing to do, because you need to pick a bass pedal that doesn’t work in the same frequencies as the guitar. Matt has a lot of weird stuff going on as well—he’s got four different heads and several different distortion pedals, all of which sound completely different. So I’ll try a number of different pedals, and work out which one fits better where you can still hear it amongst the guitars. Because sometimes you hear a great bass sound … and then as soon as the guitar comes in, it’s kind of swallowed up. The important thing is to make sure those guitar frequencies don’t clash, and that they both stand up in their own way.

n pulling it off live, are you switching pedals yourself, or do you have automatic triggers or assistance for combinations of pedals?

My bass tech, Shane Goodwin, does it all live now, which is great because a lot of the time I’m singing as well. With each album, the backing-vocal load has become bigger and bigger. So it’s nice to not worry about that side of things; there are so many pedal changes, I kind of found myself tied to the pedalboard the whole gig, and it frustrated me because I didn’t feel free to perform.

Pulling off the fast 16th-notes in the bridge of “Resistance” from the new CD, or “Assassin” or “Stockholm Syndrome” from earlier albums—are you fingering them or picking them?

On “Resistance” and “Stockholm” it’s fingers. “Assassins” is a pick. But unless the pick offers a sound that’s different, I generally play with fingers because I just don’t like the sound of a pick that often. You lose a lot of bottom end and fatness with it. So whenever possible, I stick with the fingers.

Who were your favorite bands growing up?

Mostly early-’90s American hard rock— Nirvana, Sonic Youth, Smashing Pumpkins, Rage Against The Machine … they were the songs we were playing in the cover band. Sonic Youth had a lot of noise going on; at the time we weren’t particularly good players, so we made up for that by making our guitar sound as horrible as possible. Those kinds of bands gave us the passion to want to get onstage.

Who are your three biggest influences as a bassist?

I’ve never really been into bass players, as such. A lot of players are technically incredible, but it doesn’t feel very emotional. Les Claypool, for instance. When I was growing up he was a massive hero, because what he does is just stupid, you know? Listening to Claypool definitely increases your technical ability, because when you’re growing up, you want to play like the people you’re listening to. But when you’re in a band and you’re trying to make songs that are emotional and passionate, it’s hard to incorporate that style of playing. But sometimes it can go too far the other way, where people play with real attitude and emotion but don’t have the technical ability to pull it off.

I’ve always respected Flea. I’m not a huge Chili Peppers fan, but Flea is one of these guys who’s technically very good, but he still plays with emotion and so much feeling, and a real sense of harmony and melody. Also, some of the bass lines that Brian Wilson wrote [for the Beach Boys] were incredible—in songs like “Sloop John B” and “God Only Knows,” the bass is very unusual and not obvious, rarely hitting any root notes, but still unbelievably melodic.

Who has influenced you most as a songwriter?

I think as a band; a lot of the influences come from outside of rock music. The way that Matt and I try to play, it’s more from a harmony point of view, like a string section would play together, where it’s not just a bass plugging away with root notes the whole time. In a song like “Hysteria,” for instance, there isn’t really a single point in that song where the bass sits on a root note. The bass is playing is one melody, the guitar is playing another melody, and you can almost imagine violins and cellos going. So there are a lot of times when the bass is as much of a lead instrument as the guitar is.

How has the “power trio” core of Muse affected the way you approach the bass?

Being a three-piece, combined with the way Matt plays guitar, have given me more freedom than a lot of bass players have. I don’t think there’s anywhere where he’s just banging away playing power chords. From a sonic point of view, the bass has to fill a much bigger area than what would be normal, almost like a rhythm guitar. It’s given me the opportunity to try loads of effects and distortions, and to try to create something that sounds new on the bass.

There is a lot of space to fill. Sometimes things sound great with space, but sometimes you just want to fill them up as much as possible.

Talk about your relationship with drummer Dominic Howard.

With me and Dom, it’s almost like we’re the same instrument. And it’s quite weird onstage—if Dom makes a mistake, I make a mistake right after him, and if I make a mistake, he makes a mistake. I broke my wrist in the States about five years ago, and we had a festival in England the next week, and I couldn’t play—so we had to get another bass player in. He’s actually the guy who plays keyboards for us now [live], and he’s very good, but Dom just couldn’t play with him, because we never really played with anybody else. We learned our instruments together. And the way I play is probably a direct result of the way Dom plays, which I just connect to when I’m playing.

Twenty years from now, what would you like people to think when they hear Muse and your playing?

It would just be nice to be remembered at all! If in 10 or 20 years’ time we’re not going anymore, it would be nice at least to still be respected as a good band—if people said, “You know, I still haven’t seen a concert like Muse in 2004.”

What’s your best advice to a bassist just starting out?

Be very open. A lot of people pigeonhole the bass, particularly in rock music. Listen to as many types of music as you can, outside of rock music and contemporary music as well. There’s a lot to learn about bass lines from things like classical music and jazz. And you don’t have to be a total geek about it—it’s just nice to acknowledge things outside of your comfort zone, because if you want to improve as a musician in general, you need to be educated by different types of music. There’s only so much you can learn from listening to rock bands.

And to a band of 15-year-olds out there right now dreaming of selling out Wembley Stadium?

You have to love what you do. If you’re making music for financial gain, or for celebrity status or whatever, that’s not good enough. A big part of the reason we got to where we are is because, at the end of the day, the band is based on a friendship between three people who love making music together. We’ve been together in this band for half of our lives, and the reason for that is not because we’re great musicians— it’s not because of the songs. We’re three guys who love each other as friends, and really love what we do.

Two Supermassive Bass Lines

Chris Wolstenholme's manic riffing first appeared in Bass Player in September ’04, when the hyperpowered, overdriven, all-16ths line from “Hysteria” showed folks what he was made of. Since then Chris has made a nifty habit of knocking out relentless lines consisting of deftly deployed octaves and chromatic passing tones that are way too much fun to play.

In “Unnatural Selection”, from The Resistance, Chris tunes down not just the E string (to D) but also the A to G for a rocking unison riff that flies off the fingers once you get the hang of the open G. “I think I originally played it with just the drop D, but I like to play riffs like that with open strings as much as possible. I get a much nicer sustain doing that, rather than struggling higher up the fingerboard. So I tuned the A to G and the E to D. And you suddenly realize it’s a hell of a lot easier to play.”

Next we revisit “Supermassive Black Hole” (Black Holes and Revelations) for a slower, grindier study in Muse-ology. No tricks or alternate tunings here—just an exercise in keeping the octaves and string-skipping nice and legato. Watch out for that tricky fourth ending.

Currently Spinning

The Beach Boys, Pet Sounds [Capitol, 1966]; Does It Offend You, Yeah?, You Have No Idea What You’re Getting Yourself Into [Almost Gold, 2008]

Chris Wolstenholme Muses About Muse’s Music

Showbiz [Warner Bros., 1999] “For a long time I couldn’t really listen to that album because we felt very detached from that, like the band had moved on. And it had this weird naiveté that I found hard to listen to for a number of years. But now I can appreciate it—I can almost listen to it like it’s a different band. That album was good for what we were trying to achieve at the time.”

Origin of Symmetry [Warner Bros., 2001] “This felt like the first proper record we made, where Showbiz was more of a compilation of the best songs we’d written before we got signed. It was the first time where we came off a tour and actually went to a studio to make an album. And I think that was the album where we became recognizable as what we are now.”

Absolution [Mushroom, 2003] “Absolution was more of a continuation of Origin, where we knew what we wanted to do, and we’d found our feet a little bit, and we felt comfortable with what we did.”

Black Holes and Revelations [Warner Bros., 2006] “That was probably the first album where we really felt comfortable in the studio, and it gave us the opportunity to experiment with more instruments, more synths, and things like that. We became a lot more familiar with the gear in the studio as well, because up until that point, it was easy to ask a producer or an engineer to do something for you if you didn’t understand it enough. With Black Holes we made an effort to get into the science behind everything, and we became very comfortable with that—to the point when we made The Resistance, we bought all our own gear, installed our own studio, and felt very comfortable doing it like that.

Riffing On The Resistance

Wolstenholme’s Takes On Tones From The New Record

“Uprising” That song was influenced quite a lot by [British electronica band] Goldfrapp. We wanted to create that kind of synth-y sound, without using synthesizers. With a lot of bass lines in the past, we combined distorted basses with synths to create a newsounding thing, but we made a conscious decision that the rhythm section had to be real, so we wanted to come up with a bass sound that almost sounded like a synth, but wasn’t.

“Unnatural Selection” I think we just wanted it to be fat as fuck! Even though it’s a heavy track, when you just strip it back to the guitars themselves, they’re not really overdriven. They’re sort of more crunchy. So we knew that the power of that song had to come from the bass. It was a case of just switching all the amps on, and switching both Big Muff pedals on, and both Animatos, and seeing what came out of it.

“Undisclosed Desires” It’s actually slap bass!We knew that that song wanted to go down the electronic route. Because we were going more R&B, we thought we’d go for a real chubby, plectrum-y bass sound. So we tried that and it didn’t work. I tried playing it fingerstyle, and that didn’t work. And then just as a joke, somebody said, “Why don’t you just try playing slap bass?” So I did it, and initially everyone was laughing their asses off. Then we went back and listened to it, and we thought, “If we make the sound edgy enough, it could actually sound quite cool.” So we put a Hematoma pedal on it. I had a very slight, top-endy distortion to crunch it up a little. Obviously the danger with slap bass is if you go for that super-clean, twangy, “nice” bass sound, it ends up sounding like Level 42. So we just dirtied it up.

“I Belong To You” The wah/synth is actually an acoustic/electric bass with the Akai Deep Impact pedal. We took a DI from it, and we miked it as well. I think that song had a kind of comical sound to it, and we wanted to push that a bit further. So we tried loads of stuff, and we tried electric basses with synth pedals, and nothing seemed to sit right with the piano. So we had this cheap, semi-acoustic bass that was just sitting around the studio. I’d not played it for years. It sounded quite unusual, because you don’t associate acoustic/ electric basses with synths.

Tone Generator

Basses Fender American Standard Jazz Bass, ’73 Fender Jazz Bass, Status Series II Headless, Gibson Grabber, Gibson Ripper, Noah Guitars Excalibur Bass, Pedulla Rapture, Rickenbacker 4001 and 4003

Live rig (amps, cabs) Three rigs: (1) Marshall DBS 7400 into Mills 115B bass cab; (2) Marshall DBS 7400 into Mills 410B bass cab; (3) same as (2). All three rigs are stacked sideby- side on floor behind stage, and miked. Stage monitoring is achieved with in-ear monitors plus subwoofer sidefills.

Effects Three distinct effect loops; Loop 1 goes to all three amps: Electro-Harmonix Octave Multiplexer, T.C. Electronic G-Major multieffects unit, Electro-Harmonix Big Muff p, Akai Deep Impact SB1 Bass Synth. Loop 2 goes to amp 2 only: Big Muff, Human Gear Animato Distortion, HBE Hematoma Bass Overdrive, Crowther Audio Prunes & Custard, Z.Vex Wooly Mammoth. Loop 3 goes to amp 3 only: Big Muff, Animato, Line 6 FM4 Filter, Electrix Filter Factory, DigiTech Synth Wah, Electro- Harmonix Q-Tron.

“Most of the time there’s at least two amps going at once. The only time I ever use one amp is when I’m going for just a pure, clean sound—the idea being that, when you use distortion, you lose a lot of bottom end. So, apart from things like delays and octavers, we try to avoid using distortions on amp 1, so it’s always running clean and we keep the bottom end. And then any distortions are brought in on top of that. Sometimes the Big Muff goes over the whole thing, but most of the time I just try to keep the Big Muff on amp 2. My normal, most-used sound would be amp 1 being clean, amp 2 with the Big Muff, and amp 3 with the Animato pedal.

Studio (typical signal chain) Same as live rig, plus a clean DI for backup/re-amp purposes

Strings DR Stainless Steel Hi-Beams, .045–.105 (Medium)—new strings applied on every bass for every show

![Muse - Supermassive Black Hole [Official Music Video] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/Xsp3_a-PMTw/maxresdefault.jpg)