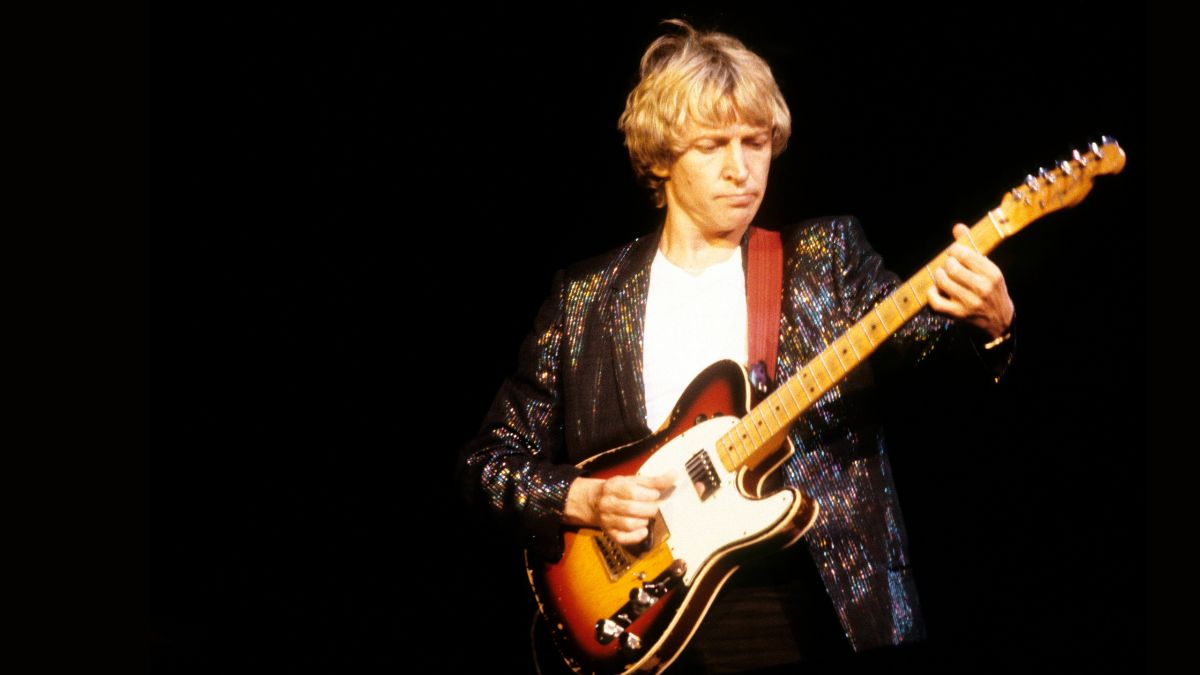

Duane Denison: ”I think a solo should break away from the song itself and bring something improvised… almost like comic relief”

The Tomahawk and Jesus Lizard guitarist on gear, why every band needs space, and bringing bossa nova flavors to a spaghetti-western-rock-metal-whatever sound

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

You can spend the best part of an hour on a Zoom meeting with Duane Denison and still come out the other end no closer to neatly describing Tomahawk’s sound. There’s no one word that will do.

Loved by open-minded metal heads, feted by alt-rock lifers and post-punk fans with adventurous appetites, Tomahawk are a rock band for whom you need adjectives to describe. Even Denison is not too sure, but maybe cinematic rock will do for now.

“It just makes me glad that we put things out and we get a reaction,” he says. “We still have our little niche, our little space in the music world. 20 years ago, when people would ask us how we would describe what we do, we would always say it was cinematic rock, and that might sound pretentious to people but that is kind of what we are doing.”

That niche was staked out in 1999, when Denison and Mike Patton met at a Mr. Bungle show and took it from there. John Stanier, formerly of Helmet, was recruited on drums, with Melvins alumnus Kevin Rutmanison on bass. Rumanison was replaced by another ex-Melvins bassist Trevor Dunn in 2013. Just looking at the roll call, at the personalities involved, Tomahawk was never going to be ordinary.

Tonic Immobility, the band’s fifth full-length studio album, is an album of complex rhythms, left-turns, rock ’n’ roll guitar, aggression and, on occasion, bossa nova. Fans of Patton’s work with Faith No More will recognize the late-90s neo-noir theatricality, the humor. Fans of the Jesus Lizard will recognize the sharp treble skronk from Denison’s guitar, the freakazoid arrangements.

There are moments when they turn you loose to enjoy the cinematic atmosphere, luxuriate in the Corbucci-esque spaghetti-western themes, but, sure as day follows night, Tomahawk spikes that reality and replaces it with a new one.

As Denison tells it, Tomahawk is many things, but above all dynamics. “You want tension and release," he says. “I think you want parts that are busy and active and full, then parts that are more spacious, and it gives the chance for things to be set up. To me, just having this relentless, overwhelming thing all the time becomes just as boring as when there is nothing happening. It is always trying to balance between those two.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

We live in an age of compression; with the tenor of the 24/7 news feed alerting us to global emergencies by the devices in our pockets; with the hyper-spectacle of contemporary cinema; with popular music mixed and mastered to dominate the airwaves and accommodate the spec of cheap ear-buds; with the rise of ambient TV, Netflix shows that can sit in the background while we check our phones, cook dinner, finish this article.

Everything is maxed out at ten. At the risk of over-playing it, maybe Tomahawk is a band for this era. Tonic Immobility has been heavily sauced with surprise. It’s an album to escape into. Not everyone will get it. But, above all, it’s the antithesis of ambient. Press play and you’ll have to stop what you are doing or turn it off until you are ready. There are no half-measures.

Duane, let’s begin with a confession. This album had to go off the first time because there is no multi-tasking when it is on. It commands full attention at all times. Was that by design?

“Music has become kind of a lifestyle accessory. It is always on in the background, and in some ways that’s fine. I’m like other people. I’ll have music on when I’m driving. I’ll have music on when I’m exercising, working out. I can understand that.

A good piece of music is like a movie or anything else. It should command our attention. It should pull you into its little sound world

“But at the same time, a good piece of music – a good album – is like a movie or anything else. It should command our attention. It should pull you in to its little sound world willingly, and there are different ways of doing that.

"One thing that we did with this album, and something that I have always tried to do – but I think we accomplished it on this one – is I want to get people’s attention but not just clobbering them, overwhelming them with parts and sounds, and guitar fireworks.”

Yes, dynamics. They are in short supply.

“On this album there is a fair amount of space. There are parts where not everything is going at the same time. Besides the fact that it gives you breathing room and you can hear what’s going on, and appreciate when everything comes in together, I feel that you give the listener’s imagination to participate with what they are listening to.”

Is there a little bit of the frustrated screenwriter in you? It sound like you game out the song for these different atmospheres – there is almost this dramatic tension to them. Listening to Doomsday Fatigue, it has this nocturnal quality…

“It should be evocative. The success of a song should be evocative – as soon as you hear it, it pulls you into that world and it is like you visualize things, you picture it. Absolutely. We have always kind of done that.

It's riffs, beats and vocals, but at the same time it has a soundscape to it, and it suggests a visual element

“Sure it’s riffs, beats and vocals, but at the same time it has a soundscape to it, and it suggests a visual element. Now, to be honest, I don’t always think in terms of visuals when writing.

"Usually, it starts off with a musical idea, and then it takes on its own life. It comes from the music rather than the other way around.”

That is one of the pleasures of music. Much of the work is done by the audience.

“I have always thought that was one of the things I like about rock music and rock as a genre. If you think about it, you’ve got all the different art forms tied into one. Obviously, you have sound and music, you’ve got the verbal side with lyrics and things, you’ve got the visual side with artwork, videos, live performances, and then you tie it all together so it makes a very powerful statement.

“You take any one thing by itself and people get bored. People get bored of just going to the symphony, or just reading books at the library, going to a museum and looking at art. But when you have got it all together happening at once, it’s fun and exciting. That to me is what rock should be.”

Your sound is so different, so challenging, we talk about it being avant garde or whatever. But your tone is fundamentally rock ’n’ roll. When you strip everything back, it comes back to this clean twang that’s not so far from Duane Eddy.

“Absolutely. I have always tried to straddle those worlds, between the artistic sort of avant garde or modern art side of the guitar world – and I have a degree in music – but at the same time there’s the rock.

Sonically, with guitars, I always like a certain amount of twang and a certain amount of crunch, and going between the two

"I love rockabilly. I love early rock guitarists, whether it was Scotty Moore or Eddie Cochrane, Chet Atkins, people like that, and to me, it all comes back to energy and excitement, and being evocative of that world. That never changed.

"Sonically, with guitars, I always like a certain amount of twang and a certain amount of crunch, and going between the two. That is what it all comes back to.”

And it never goes out of style.

“Electric guitar, it just seems like every four or five years there is a quantum leap with what people are doing. And I have been at it so long, that when I see some of the new guitar players, like Tosin Abasi playing seven-string and just doing things that are almost beyond my comprehension. How are they doing that?

I respect innovative things, but I still like a certain amount of the old traditional things, where it is all about the simplicity of the idea

“On the one hand, I respect the innovative things, but I still like a certain amount of the old traditional things, where it is all about the simplicity of the idea, and always trying to balance between those two.”

We need balance between those fundamental pillars and the new outposts that challenge them.

“You could look at Chet Atkins and Buckethead. For me, at this point, I can only do so much. I can only practice so much, and I don’t worry about trying to keep up with the latest shredder.

“When I was first learning guitar, the shredders of my day were the prog guys and the fusion guys – Robert Fripp or Steve Howe, Jan Ackermann, people like that. Those guys were the heroes when I was teenager, then punk rock came along, and the post-punk thing, and this more minimalist, stripped-down mentality came along, and that was a big influence, too. That’s where I’m coming from.”

When you become the player that you are, you don’t have to chase the latest techniques.

“If you look at anyone who has been around for a while, whether it’s Chuck Berry – well he’s not around anymore – or David Gilmour, whoever, you strike a balance. You become known for a certain thing, and you have a certain sound, certain techniques, and it is your style, and so over time you develop it and refine it but you don’t stray too far from it because that is who you are. That is what makes you unique.

You have to stick with what you've got, and then try to add new things

“It’s like you said: every time someone new comes along, you keep copying them and you end up being a bad version of them. Every so often someone would come along – whether it was Hendrix or Van Halen – who just upsets everything, and it makes you rethink, but you can’t copy them.

"You have to maintain a balance between defining your style and not repeating yourself too much. It’s about trying to stick with what got you here, what it is you like, what people like about what you do, and then trying to add new things a little bit at a time.”

We can talk about gear and so on, but sometimes the best effect a guitar player can have is a vocalist to bounce off. Has playing with Mike and David changed your style?

“Yes, absolutely. For instance, there is a little bit of difference between the Jesus Lizard and Tomahawk. With the Jesus Lizard, it was a little bit more of a stripped-down, four-piece band – guitar, bass, drums and vocals, and with a very raw singer, who’s not singing beautiful melodies every song.

"In a situation where it is fairly stripped down and raw, to have a really processed guitar sound would just sound awful. It would sound ridiculous and out of place, so I kept the guitar as stripped down and straightforward as possible.

There is a reason guitars are here and it's not to recreate keyboard sounds

“For years, I had a Travis Bean I plugged straight into a Hiwatt and that was that. Also, we would play these gigs that were sheer mayhem onstage, and if you had a pedalboard it was going to get destroyed.

"With Tomahawk, Mike is more of a singer, where he can hit melodies and intervals and notes more consistently. He’s using a sampler and electronics, so I felt like I was free to start introducing more and more effects.”

Such as?

“It’s funny, I always comes back to the same ones, the ones that came out in the '50s – reverb, tremolo, slap-back, and then slowly, then different types of delay, gated delay, duck delay, maybe a touch of chorus here and there If you listen to the new album, that’s pretty much it.

“There are things I really like. The Line 6 Helix. I still like the TC Electronic G-Force which I have had for a long time, and so between those two I can get pretty much any sound I want.

"There comes a point for me when it doesn’t even sound like a guitar anymore, then I ask myself, ‘Why am I doing this? If it sounds like something you could do on another instrument why are you doing it on a guitar? There’s a reason guitars are here and it’s not to recreate keyboard sounds.”

The journalist’s perspective on this is that it causes great angst trying to work out whether something is really a guitar, and, if so, how is it being done?

“Sometimes it is cool. I use a Fernandes Sustainer in a guitar, and you can do cool things with that, and I know there are people who use those so that you can’t actually tell whether it is a guitar or not – and there is an art to that, too. It’s just that, for what I do, no matter what effects are there, it’s an electric guitar and that is what it should be.”

There are some Hiwatts sitting behind you, but what did you use on the album?

“I used my Hiwatt, Fender Supersonics, which I am a fan of, and I used a Marshall JCM, and I used a Blackstar HT-Stage 60. A lot of times, when we play, especially when going out of the country, we have to rent things, and I just started using the Marshall JCMs because they were so good and consistent.

"I’m not saying the Hiwatts weren’t consistent, but I tend to play around with different tubes and certain sounds, and when I use rentals they don’t sound the same. I had good luck with Blackstar, too. I think they are quality, reasonably priced.”

Blackstars seem to be having this conversation with themselves, with the ISF function and what to do with the mids…

“I typically take midrange out no matter what amp it is. Not completely scooped but definitely pulled back. I prefer brighter, sharper high-end and a tight bottom. That is what I’m always going for. It’s funny, I saw some video footage of myself playing in a band from the 1980s, a band called Cargo Cult in Austin, Texas. And it sounded exactly the same!

Guitar players will sit in a practice room by themselves and tweak their sound, and then you mix it in with other things and it is not going to sound like that anymore

“I was using a Lab Series L5 with a little bit of reverb, a little bit of chorus and crunch. Nothing has changed. I don’t want it too fat or chunky, or opaque. Too much midrange and the chords and riffs tend to get muddy, and I want those to jump out. It also depends on guitars and strings, too.”

And your bandmates…

“That’s another mistake that guitar players and bass players make. They’ll sit in that practice room by themselves and tweak their sound endlessly and get it just right, and then you mix it in with other things and it’s not going to sound like that anymore.”

For guitars, were you on Kevin Burkett’s aluminum-necked guitars?

“I used the Electrical Guitar company, all aluminum. I used the one with P-90s a lot on this record. Then I pulled out the Gibson ES-335 for a few things. That and, believe it or not, a Schecter Solo II Special that was given to me, and you know, I plugged it in and thought, ‘There is nothing wrong with the way this sounds.’”

Schecters are underrated. What they lack in the cultural kudos they make up for with performance.

“The necks are so slim! At first I was like, ‘This is built for a child!’ But it is pretty comfortable, and it feels pretty great. We put it on a track and it sounded really good. What is not to like about it?”

Everyone who uses an EGC guitar loves them. Why aren’t they a lot more popular?

“I don’t know. They are not the first to use aluminum for necks and bodies. I had a Kramer back in the late '70s and then I had Travis Bean through the '90s, and now I have these, and each generation gets better.

"To me, the most important thing about a guitar is the feel, because you can change the way it sounds or change the way it looks in any number of ways but you can’t change the way it feels.

The most important thing about a guitar is the feel, because you can change the way it sounds or the way it looks, but you can't change the way it feels

“A humbucker pickup set in an aluminum frame is just a wonderful thing, because you’ve got the high output and the chunkiness, the natural thickness of a humbucker, but when it is in a metal frame it gives it more focus, a little more clarity, and a brighter sharper edge. It lends itself to a certain style of music and that’s why people like me tend to play them.”

How did you write the solo for Fatback?

“You try to think what is right for that one particular song. It’s funny, that main riff is in 13/8 time, and that was deliberate. I thought, ‘I am going to write the most evil riff ever.’ But then the chorus and the chords around the solo are in 4/4.

"Because it has got this sort of busy, chugging line, the first half of that solo I am almost playing one note the whole time, or one note with embellishments, and then it cuts loose.

I think of the solo when you break away from the song itself, and you bring in something that almost should be improvised and almost like a comic relief

“I honestly don’t spend much time thinking about them. I almost think of the solo when you break away from the song itself, and you break away from what the vocals did, you break away from the riff, and you bring in something that almost should be improvised and almost like a comic relief.

“I used the same idea on the second song, Valentine Shine, where there are some parts where it is just noisy, linear, crazy stuff and it is meant to just be a diversion while the singer catches his breath and gets ready to give you more propaganda.”

Let’s talk a little bit about the spaghetti-western influence, because those Corbucci-esque soundtrack moments come and go and they are a delight.

“Some things show up regularly on an album. There is always that spaghetti-western, Morricone-meets-whatever kind of vibe, and there has always been this touch of Latin stuff here and there.

"Maybe not quite as obvious, but on Howlie, it was almost bossa nova-meets-flamenco – but not like the Gypsy Kings, like some virtuoso crazy thing but on the side, in an atmospheric way.

“There are elements of prog rock in there, too, like on Tattoo Zero, where it has that long instrumental section in the middle. Like anything, you can overdo it. If you do too much of something, and it sounds like a parody or a caricature, or starts to sound stale, the trick is to always find some new thing to mix in with it to freshen it up.”

Absolutely, adjust the seasoning and take it from there. There are what sounds like ska rhythms on some of these parts.

“I’m a big fan of dub and reggae and ska. I like that style where it’s choppy and rhythmic, and effects are used to create atmosphere. On Recoil, the rhythm guitar is very much based on RnB and reggae guitar… Ernest Ranglin is one of the great guitar players, though he is not strictly a reggae player – he does jazz and calypso as well.

I don't want to copy my influences. It's internalizing them and having this unconscious thing come out in a different way

“I listen to a lot of different types of guitar styles, whether that’s some of the different African guitarists out there, like D’Gary or Touré. It goes in the ear and maybe you process it with your own thing.

"I don’t want to copy them. I don’t want to present a whitewashed version of them. It’s internalizing them and having this unconscious thing come out in a different way.”

And hope it all makes sense…

“It’s funny, you work really hard to come up with a unique, original style, but then from a commercial standpoint, you have to find a way to balance that out with something that is a little more familiar and common to listeners, otherwise it won’t connect with people.”

Tomahawk’s new album, Tonic Immobility , is out on March 26 via Ipecac.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to publications including Guitar World, MusicRadar and Total Guitar. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.