All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Many years ago, I had a band called Greg Koch and the Tone Controls, and in 1993 we released our first album, eponymously named. The music that we played was primarily blues-based, but we generally tried to push the ball down the field a little bit by adding some unexpected chord changes and harmonic devices. A good example is the song Mean Streak, which will be the focus of this lesson.

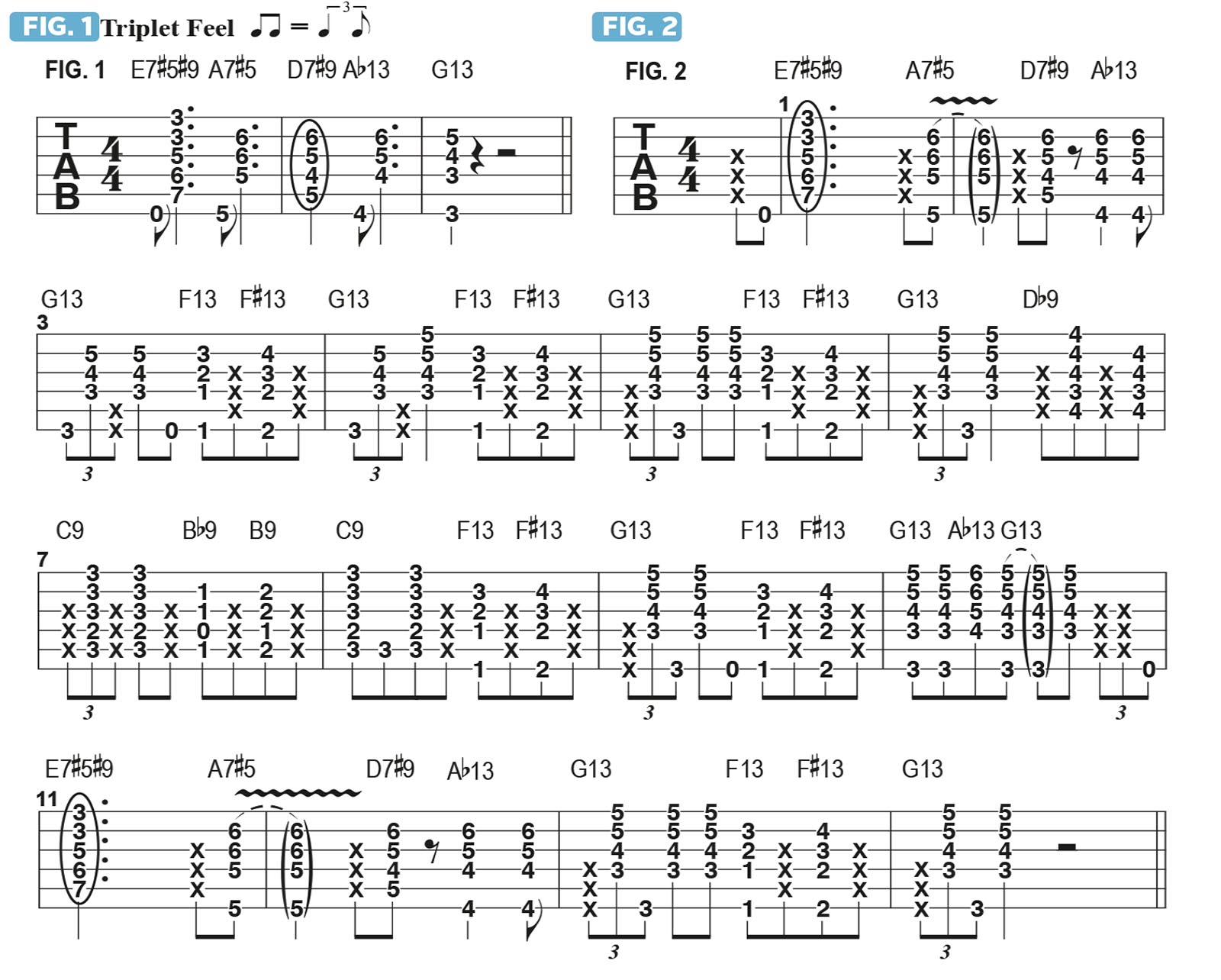

Mean Streak is a funk shuffle in the key of G that stays within the “blues changes” parameters, before venturing into a more unusual and harmonically challenging turnaround, as shown in Figure 1.

Across this two-bar phrase, I begin with E7#9#5, voiced with a wide stretch that spans the 3rd-to-7th frets, followed by A7#5 – D7#9 – Ab13. As you can see, a high F note resides at the top of these last three chords, serving as a common tone while the inherent harmony develops underneath it.

In Figure 2, I demonstrate how this turnaround functions within the structure of the tune across the full 14-bar form.

Following the turnaround, the song settles into a shuffle groove that essentially moves from the I chord, G13 – which I embellish with a repeating chromatic ascent, from F13 to F#13 to G13 – to the IV chord, C9 (more chromaticism included via the Db9 – C9 descent, as well as the Bb9 – B9 – C9 ascent). This is followed by a return to F13 – F#13 – G13, and then a restatement of the turnaround.

Combining the shuffle groove with the eighth-note syncopation and the chromatic accent of F – F# – G is something I picked up from the classic John Mayall tune Suspicions (Pt. 2), which I discovered via a great compilation album, Looking Back, that was released in 1969.

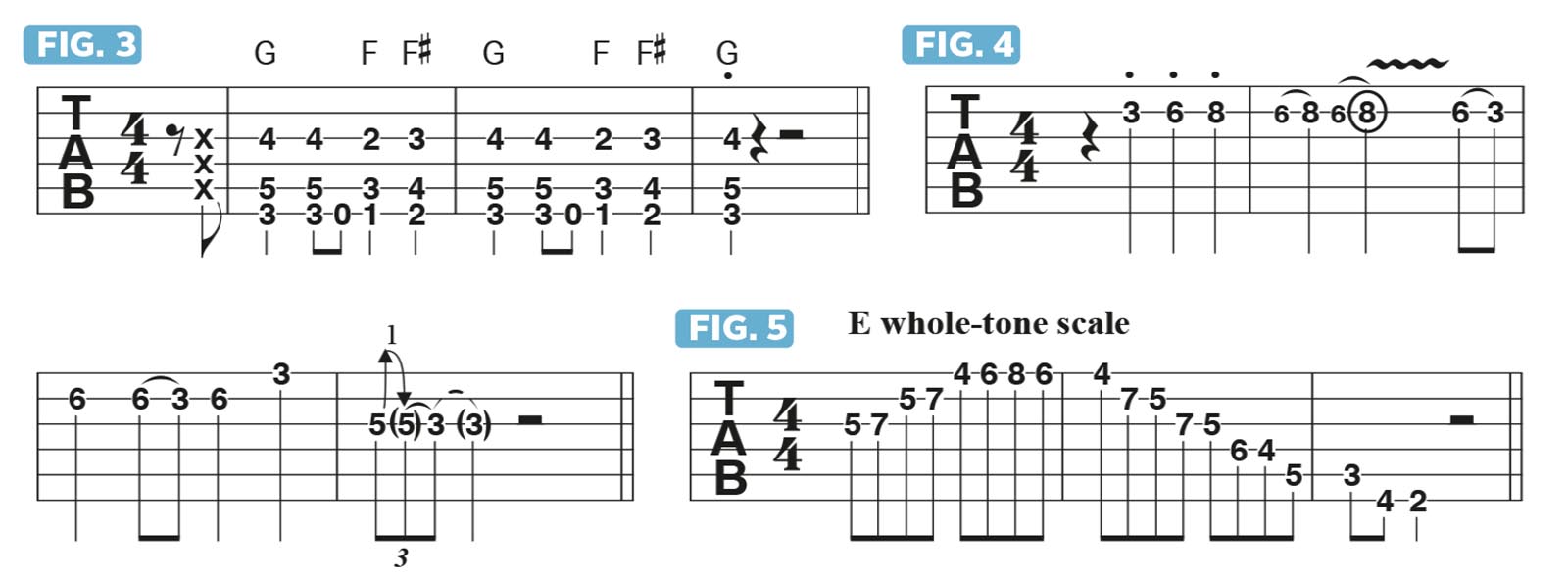

Figure 3 illustrates a rhythm part along the lines of Suspicions (Pt 2), and Figure 4 represents a similar melodic line played over the basic groove.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

I “funked up” the approach here by expanding the basic dominant 7th chords to 13ths. When fretting these grips, I’ll often hook my thumb over the top of the neck to fret the sixth-string root notes. If this unconventional technique feels uncomfortable or arduous, you can of course form the chords in the normal way, with the index finger fretting all 6th-string roots.

There are, of course, many different options one can take when soloing over this turnaround, but one tried-and-true approach is to play the E whole-tone scale (E, F#, G#, Bb, C, D) over all of the chords

When soloing over the “bluesy” part of the tune, I’ll generally rely on typical minor pentatonic-, blues scale- or Mixolydian-based phrases. However, when soloing over the turnaround, the more-complex inherent harmony invites a broader scope for note choices.

There are, of course, many different options one can take (which we will explore in depth in another column), but one tried-and-true approach is to play the E whole-tone scale (E, F#, G#, Bb, C, D) over all of the chords.

Although some of the notes may clash a bit with specific chord tones across the progression, I find that the ear “accepts” this twisted angle if you can devise effective ways to make it work. For me, there is virtually an endless variety of ways to travel through whole-tone ideas, so I encourage you to check out this multi-purpose scale.

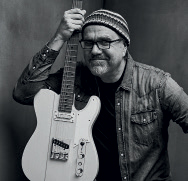

Greg Koch is a large human who coaxes guitars into submission in a way that has left an indelible print on the psyches of many Earth dwellers. Visit GregKoch.com to check out his recordings, instructional materials, signature musical devices and colorful hats.