West African grooves: energize your guitar playing with new rhythmic colors and concepts

Learn the fundamentals of African guitar approaches with this in-depth lesson

The rhythms of West Africa helped shape 20th-century music, and continue to inspire today’s artists. In this extended lesson, we go back to source, exploring two of the region’s great traditions - the kora harp playing of Malian jali musicians, and polyrhythmic Ewe drumming from Ghana.

Most of today’s music has direct ancestry in the intricate rhythms of West Africa. Some such links are readily apparent - it’s not hard to guess at the African roots of Latin America’s percussion instruments, and blues fans are well-aware of the genre’s origins in the spiritual songs of Transatlantic slaves. Blues, in turn, is a parent of rock, jazz, funk, and virtually all other popular music styles of the modern era.

Much of West Africa’s vast imprint still goes unheralded, and the contributions of African musicians are all-too-often written out of the history books.

But much of West Africa’s vast imprint still goes unheralded, and the contributions of African musicians are all-too-often written out of the history books. How often is it mentioned that that J.S. Bach’s canonic sarabande dances have origins in Berber dance rhythms from the Sahara? Or that Brian Eno’s looping electronic innovations were in part inspired by an obsession with powerhouse Nigerian drummer Tony Allen? Or that Indo-African folk fusion has been around for centuries, created through waves of Bantu migration to the Subcontinent’s Western coast?

This lesson gives a rhythmic taste of two extraordinary traditions from West Africa - the kora harp playing of Mali’s jali lineage, and Ghana’s polyrhythmic Ewe drumming. Placing non-guitaristic ideas on the fretboard always helps to catalyze fresh creative imagination, and these exercises also foster new connections with songs we already know. How could learning the deep roots of modern genres do anything but enhance your appreciation for them?

All music is in some way a profound reflection of its circumstances. So to better understand the sounds, we will also explore some of the human lives, routines, and beliefs behind them. Cross-cultural borrowing must always come from a place of open-minded respect, and musical ideas will only yield their full blossom when connected to their real-world contexts.

Offbeat phrasings, rhythmic flurries: Kora harp playing from Mali

Malian music is one of Africa’s ‘breakout’ traditions. Or rather, set of traditions - the country is vast and diverse, with 12 official languages and dozens of ethnic groups.

Mali’s music is a limitless source of ideas for the open-minded guitarist. Here, we will turn to the kora, a 21-stringed harp-like instrument played with a hypnotic two-handed fingerstyle. It is popular in the country’s Western region as well as in nearby Guinea, Senegal, and the Gambia.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Like the guitar, the strings of the modern kora are often made from nylon, giving a loose, percussive snap on impact. But the resonance that follows is weightless, with a gentle, evenly balanced texture

Like the guitar, the strings of the modern kora are often made from nylon, giving a loose, percussive snap on impact. But the resonance that follows is weightless, with a gentle, evenly balanced texture. There is no fretboard to worry about, and musicians use the corresponding one-note-per-string constraint to explore a fascinating range of rhythmic-melodic articulations.

Kora music is inseparable from the region’s jali tradition (also known as the griots), a lineage of multi-skilled performers who also draw on poetry, storytelling, oral history, and a range of other creative forms.

Listen to Toumani Diabaté, the instrument’s greatest living master, perform Kaouding Cissoko, named for a revolutionary Senegalese kora player who died far too young in 2003. Diabaté’s tribute features rapid solo lines, but also leaves plenty of space for the notes to blend into one another.

A kora’s strings, like those of the Western harp, will continue to vibrate unless deliberately muted - listen to how many of the notes just fade gradually into silence, giving a calming, ethereal quality even in passages of high density. The resonances effectively creating a ‘moving harmonic average’ of the melody, smoothing its colors like light refracting through water:

First, just aim to lose yourself in the flow. Then, start paying conscious attention to the role of three key ideas - the offbeat melodic phrasings, florid rhythmic outbursts, and static ostinato ‘bassline’. Such is Diabaté’s two-handed virtuosity that you sometimes have to remind yourself that he’s the only one playing.

As with all the other exercises, we’re aiming to absorb some of the music’s distinctive, essential elements rather than to copy it exactly. But even a liberal kora-to-fretboard translation will teach us a lot about what we might have been missing on our own instrument.

We guitarists are too fond of wandering around the same old physical shapes - turning to the music of other instruments forces us to take a more expansive view of our fretboard’s geometry (the process effectively forces you to find new ‘snakes and ladders’).

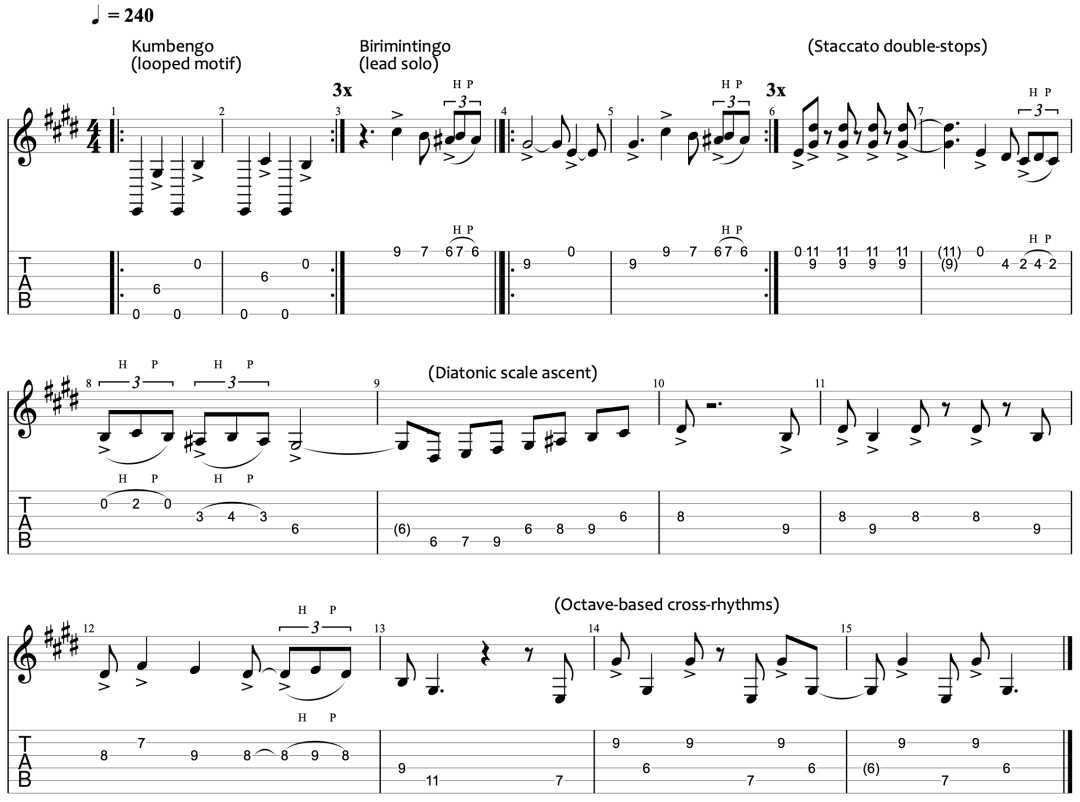

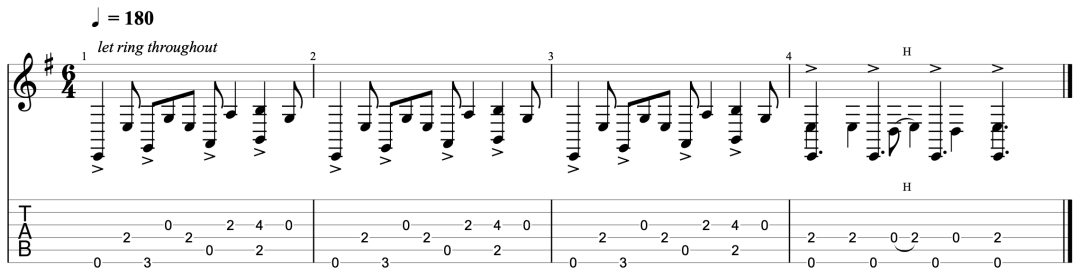

The short study below draws on ideas from Diabaté’s captivating sound. Underneath we have a static four-note ‘bassline’ loop (known as a kumbengo), notated in bars 1-2, with a lead line (birimintingo) to go over it, notated from bar 3 onwards. The solo showcases a few quintessentially kora-like ideas, including:

- Triplet note flurries (bars 3, 5, 7, 8, 12) - use confident hammer-pulls

- Staccato double-stop interjections (bar 6) - make them really abrupt

- Unbroken diatonic scale runs (bar 9) - hit the final note hard

- Octave-based cross-rhythms (bars 14-15) - maintain steady dynamics

- Pure pitches (throughout) - avoid vibrato, slides, and bends, which are all unplayable on the fretboard-less kora

Ex 1 - Kora-style study composition (both layers)

Approach it openly, by playing/singing along and then using the ideas as the basis for your own improvisations. See which picking approach fits you best - you can fingerpick, use a plectrum, or mix both (maybe try out a pick-and-fingers hybrid for the final two bars).

Here are two kumbengo backing loops to practice over, at a slow 145 and then the full 240bpm. It takes some time to get the triplets down at speed:

I find that using a hard plectrum quite aggressively near the neck can capture some of the kora’s attack patterns even on a light-gauge Strat, but real fingernails and a nylon-string guitar are by far the most convincing combination.

(Listen to classically-trained guitarist Derek Gripper’s fantastic kora reworks to see how far this has been taken - and he has a 15-minute lesson on it.)

Also hear how there isn’t really a definitive root note. While the open E string provides an unchanging, rhythmic drone, the ambiguous phrase resolutions and offbeat syncopations can tempt us into hearing B as the melodic ‘centre of gravity’.

This dual modality brings a sense of suspension, suggesting both low E Lydian and a higher B Major (the former has a stronger root, but we are more familiar with the latter’s scale shape). You don’t have to choose which ‘key’ it’s in - just think about the rises, falls, and pauses, and consider where each phrase is headed.

Mathematics of life: Ewe polyrhythms from Ghana

Polyrhythm is perhaps West Africa’s most distinctive musical concept. The idea of layering two rhythms against each other is far from unique to the region, but few other cultures have applied it with more power than the Ewe drummers of Ghana, Togo, and the surrounding area. A five-million-strong ethnic group, the Ewes have long given percussion a central place in community life, with huge ensembles accompanying everything from dances and weddings to funerals and war marches.

Let Ladzekpo guide you through the core patterns of Ghanaian polyrhythm, in a workshop with students in Berkeley, California.

Again, start by just getting into the immediate flow of the sounds (how do they make you want to move?). This is the only route to the music’s inner essences - in his words, Ewe drummers “don’t think... in terms of beats, and numbers, and the mathematical, and these things...we hear emotions”.

Aim to process the sounds intuitively, sampling the vocab rather than fretting about the details. Tap along with your hands before getting too far into the analysis, which we will cover later - once your mind is well-versed with the shapes, the theory will fall into place.

Ex. 2a - The basic 3:2 ‘building block’ of Ewe rhythm

We will now focus in on the basic 3:2 polyrhythm, described by Ladzekpo as the “foundation of our music”. A three-cycle is played over a two-cycle so that both occupy the same total time period, creating a concise ‘building block’ that can then be looped, stretched, cut up, and permuted in all manner of other ways (Ewe drumming isn’t so far from sample-based electronic music in this respect).

First, we will familiarize ourselves with it by ear - listen to the following loop and tap along until you can comfortably keep the pattern up. There’s no need for a guitar at this stage, as we’re just aiming to internalize the flow. (Advanced level: learn to hold a conversation at the same time - maybe a basic courtesy if, like me, you’re going to annoy your housemates by impulsively tapping on your desk all the time).

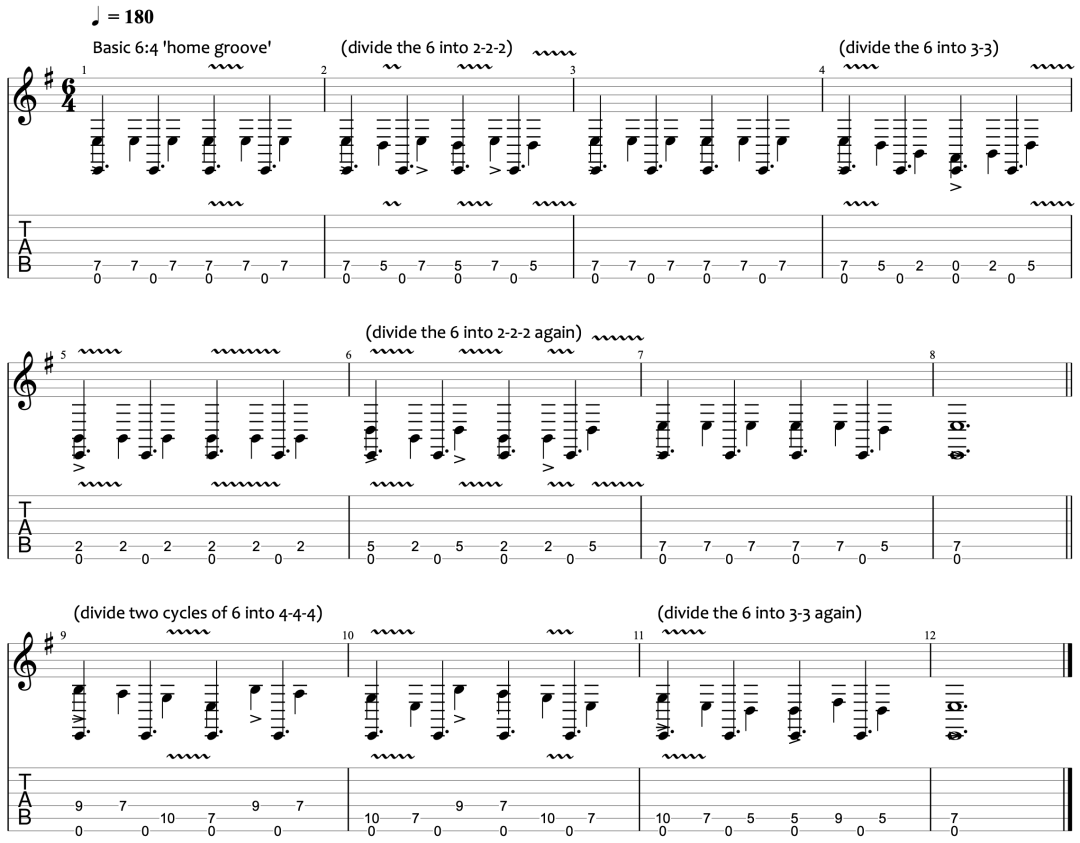

Ex. 2b - Subdividing 6:4 polyrhythms on the guitar

Now, we will place these ideas on the fretboard, and try out a few ways of dividing up the 6 layer. For this exercise, the 3:2 is turned into a 6:4, simply by playing it twice and counting across both. Conceptualizing things as a 6 gives us more flexibility, with a longer overall pattern to play with (‘more Lego bricks’).

In the first bar, we explore one way of playing the basic 6:4 ‘home groove’. Again, there are a variety of effective picking approaches. Fingerpicking with the index and thumb will give a more metronomic, ‘snapped to the grid’ feel, whereas playing with a pick is rougher, with a dynamic unevenness and slight time delay between any pair of notes played at the same time (you can’t literally hit two strings at once with a plectrum).

I prefer a pick, which maximizes power and volume - even unamplified, Ghanaian percussion can be loud enough to resonate through an entire town (kind of like an all-acoustic radio station).

I haven’t noted which exact ornamentations to use - this should come from you - but consider sprinkling in some slides, vibrato, and hammer-pulls to humanize the sound. West African percussion ensembles often feature singers, pitched drums, and tuned bells, giving the music a vocal quality. See how much life you can draw from the ratios with your own embellishments.

As the exercise progresses, we encounter a few different ways of dividing up the rhythm’s top layer. In bar 2, the 6 becomes a 2-2-2 - bring this out by really emphasising the first beat of each pair.

In bar 4 it becomes a 3-3, with both these patterns being reprised later on. In bars 9-10, the 6:4 is doubled into a 12:8 (four times the original 3:2), allowing for even greater subdivisory freedom - 12 is a ‘highly composite number’, divisible by 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and itself (we divide our clocks into 12 hours for similar reasons).

Here, we subdivide the 12 into 4-4-4, bringing an ambiguous momentum:

Feel how polyrhythms such as these open up completely unique dimensions of musical tension. Many describe the sensation in terms of having your mind pulled in two different directions at once, although it’s more accurate to say that your mind is being pulled in the same direction at two different speeds. Either way, there really is no other perceptual experience quite it.

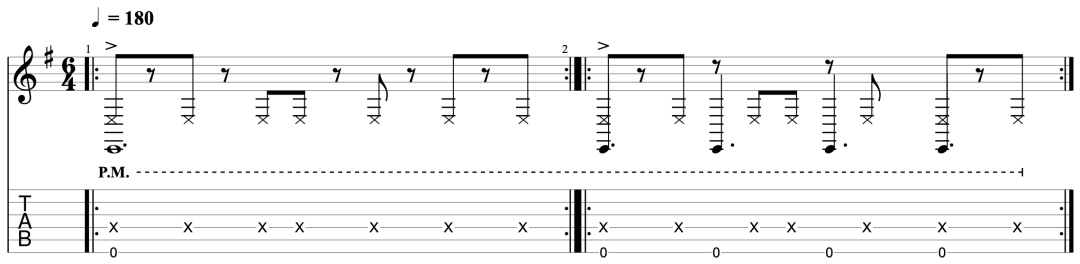

Ex. 2c - The 12-beat Ewe ‘Standard Pattern’

Now, we will add in the 12-beat Ewe ‘Standard Pattern’, first introduced in Ladzekpo’s masterclass. Its idiosyncratic, irregular shape, often looped on the gankogui bell, is core to Ewe rhythm. Listen to it ‘pure’ in the following short clip, again preparing yourself to play it on the guitar by tapping along:

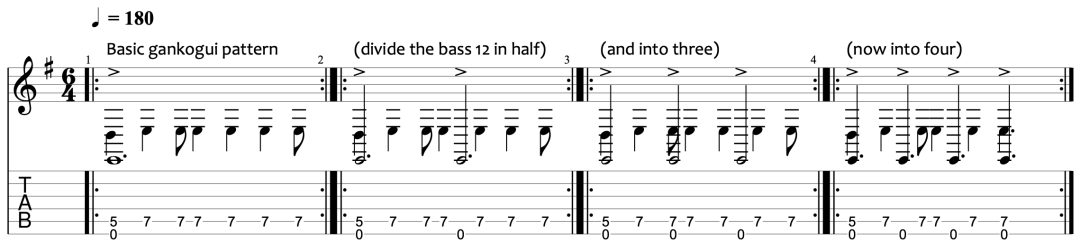

Ex. 2d - Subdividing the Standard Pattern

Next, we will combine the Standard Pattern with rhythmic stabs on the 6th string. This is deceptively difficult to nail down. Loop up each bar at will - this one is just vocab rather than a structured composition (try mixing and matching later on).

Ex. 2e - Arpeggiating the Standard Pattern

You can ‘hide’ the gankogui pattern in other styles of music, exploring different aspects of its flow in each setting. For the final exercise, we apply it to some familiar guitaristic territory, working around an open Em7 chord.

It almost sounds like a folksy, singer-songwriter riff, but is rhythmically comprised of nothing but the Standard Pattern over a four in the bass. Fret the 4th string with your middle finger:

Ewe polyrhythms such as these have captivated Western musicians for decades. Steve Reich’s canonic minimalist work Drumming was inspired by a five-week stay in Ghana, studying under master Ewe percussionist Gideon Alorwoyie.

Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers backed their leader’s solos by playing the Standard Pattern on sticks and bells, visibly shocking audiences of the early 60s with their powerful polyrhythmic soloing (at the very end Blakey hits his cymbal so hard it falls off its stand).

Cream’s late firebrand drummer Ginger Baker was addicted to West African music (amongst other things) for virtually all his career.

Polyrhythmic symbolism

What is the human significance of these sounds? What, in the end, is West African polyrhythm really all about? In Ladzekpo’s words, “the main scheme [4 layer] is symbolic of your own purpose in life, and the way you’re supposed to maintain it - to be strong, and dynamic...nothing can push it away...The other beats [6 layer]...become some kind of obstacles. So you have your purpose in life, and crashing against it are all these obstacles.”

It goes without saying that this lesson is just a taster, designed to spark some new ideas and fresh approaches to the guitar, while also introducing you to the cultures and traditions behind them.

Broadening your musical toolbox will allow you to express yourself more freely - and why not look beyond the instrument’s established repertoire in your search? This way, you will never run out of ideas.

Ghanaian polyrhythm: further listening and learning

—Drums of Death: Field Recordings in Ghana, showcasing a wide range of Ewe and Ashanti funeral rhythms, is for me one of the most astonishing percussion albums ever recorded. Funeral drumming is a distinctive facet of Ewe culture, with dozens of performances captured respectfully on YouTube. Watch the call-and-response of the Wa people, the warlike lamentations of the Agbadza style, and the massed drum ensembles at the procession wake of Osabarima Dotobibi Takyia Ameyaw II, the late Chief of Techiman.

—Demo lessons don’t get much better than Ladzekpo’s Principles of Polyrhythm from Ghana series. We watched Part 2 above - see here for the full 4-part series (45 mins total). Also check out bassist-composer Adam Neely’s rundown of 4:3 Polyrhythms in top 40 pop music (5 mins), and Peter Magadini’s Polyrhythms for the Modern Drummer.

—Renowned Ghanaian musicologist Kofi Agawu argues that Ewe rhythm (and perhaps all rhythm) is best understood through through the lens of spoken language. He discusses his work in this superb Library of Congress lecture, comparing different forms of rhythmic expression in Ewe life including dance, drumming, song, poetic narration, and everyday conversation (1hr 40mins).

—You cannot truly steal a musical pattern, but those of us who duplicate the ideas of disparate traditions for our own purposes must represent them properly, and inspire others to investigate their fuller origins. Watch rapper-scholar Akala - who in 2008 travelled to Mali to collaborate with Gambian, Ghanaian, and Moroccan musicians - eloquently discuss cultural appropriation in this short video, covering his own upbringing and the erasure of black artists from Western accounts of music history (7 mins).

George Howlett is a London-based musician and writer, specializing in jazz, rhythm, Indian classical, and global improvised music.