“If I were to strum a full barre-chord voicing for each chord, it would feel too ‘chunky.’ Instead, I do what Nile advised me to do”: Cory Wong on the most important technique you can learn from Nile Rodgers

This month, I’d like to talk about the paramount importance of the right, or pick, hand – how it’s the keeper of time and the thing that gives us the groove while we play.

I’ll demonstrate some examples and practice tips for you to work on to help develop your strumming technique.

When it comes to strumming, I subscribe to the “steady motor” method, keeping my hand in perpetual motion, in an unbroken down-up “pendulum” pattern, most often in a 16th-note rhythm, even when I’m not hitting every 16th note.

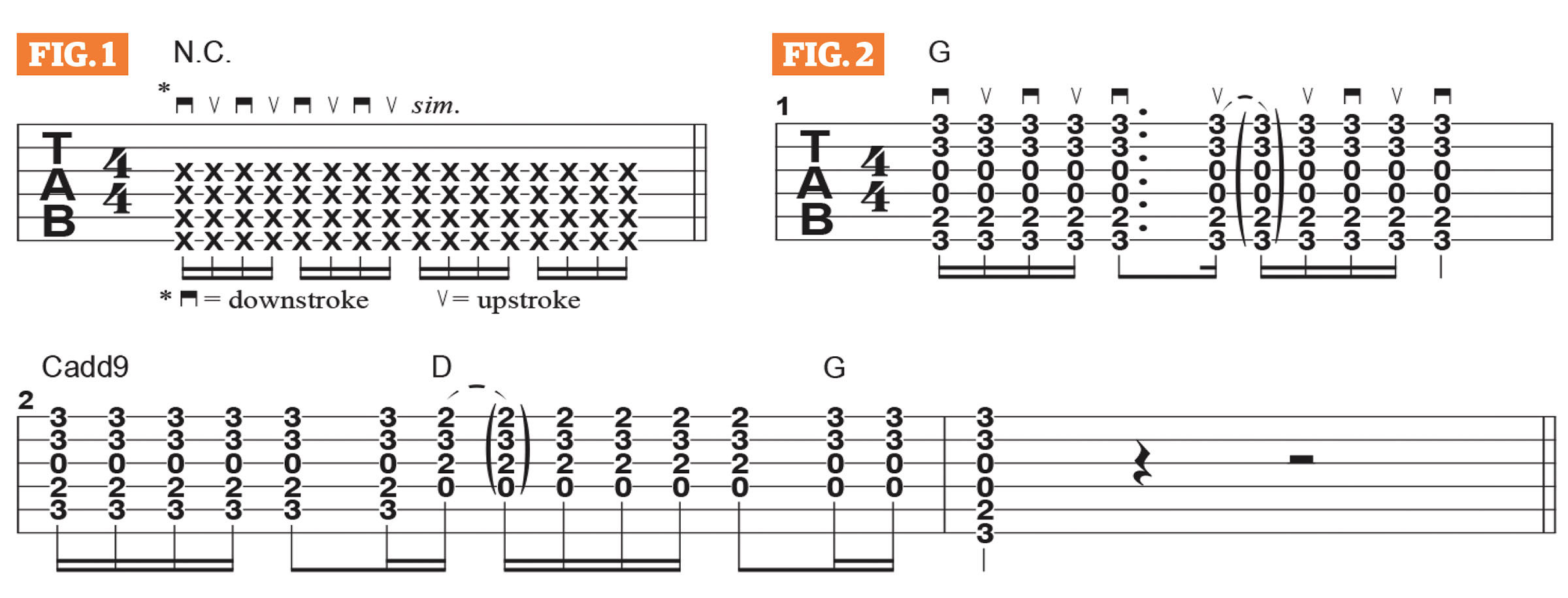

As shown in Figure 1, I’m strumming steady 16ths in an alternating pattern while dampening all of the strings with my fret hand.

In Figure 2, I apply this strumming technique to a chord progression. Notice that, in bar 1, on beat 2, I strum G5 and let it ring for the equivalent of three 16th notes as my hand keeps moving before striking the chord again. In bar 2, I switch to eighth-note accents on beats 2 and 4.

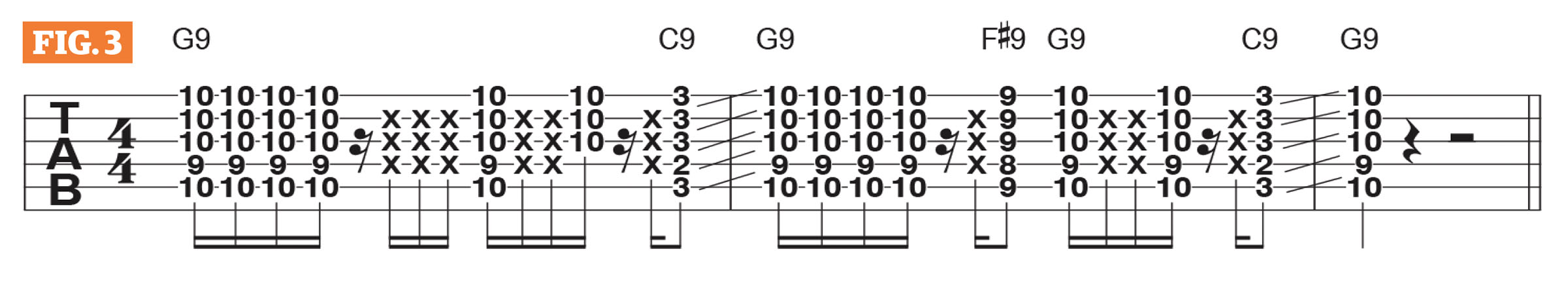

In Figure 3, the technique is applied in a funk context. Here, I repeatedly strum a G9 voicing, interspersed with muted-string accents.

In all three examples, my right hand is doing the same thing, moving down-up-down-up in 16th notes, which may be counted “1-ee-and-uh, 2-ee-and-uh, 3-ee-and-uh, 4-ee-and-uh.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Any note or chord that falls on a downbeat (“1,” “2,” “3” or “4”) or eighth-note upbeat (“and”) is sounded with a downstroke, and anything that falls on the second or fourth 16th note of the beat (“ee” or “uh’) is caught with an upstroke. This way, I never have to think about my strokes, as the continuous motion will make those decisions for me.

Are there times when I’ll change my strumming approach for a unique musical situation? Absolutely – this is just a general guideline.

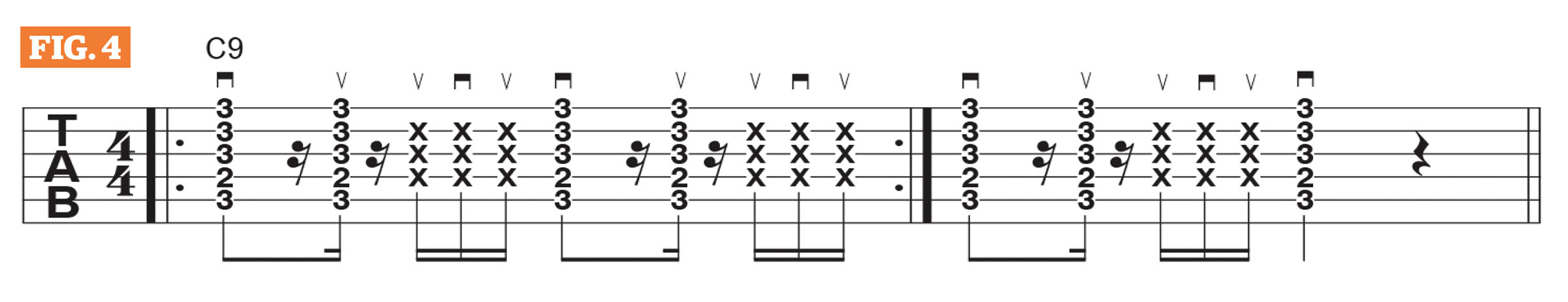

When moving my hand like this, I don’t always strum the strings, even though the down-up motion is constant. There are three sounds that you can get: a chord (or note), a muted-string accent (“x”), or nothing at all – silence. In funk-style music, the most effective rhythm parts combine notes, chords and dead-string accents with space, which together create the desired syncopated rhythms.

Figure 4 illustrates an example of this. On beats 1 and 3, I sound C9 on the downbeats and on the last 16th-note upbeat (“uh”). On beats 2 and 4, the downbeats are silent while the muted-string accents through the rest of the beat are strummed in steady 16ths. In those holes of silence, my right hand is swinging over the strings without touching them.

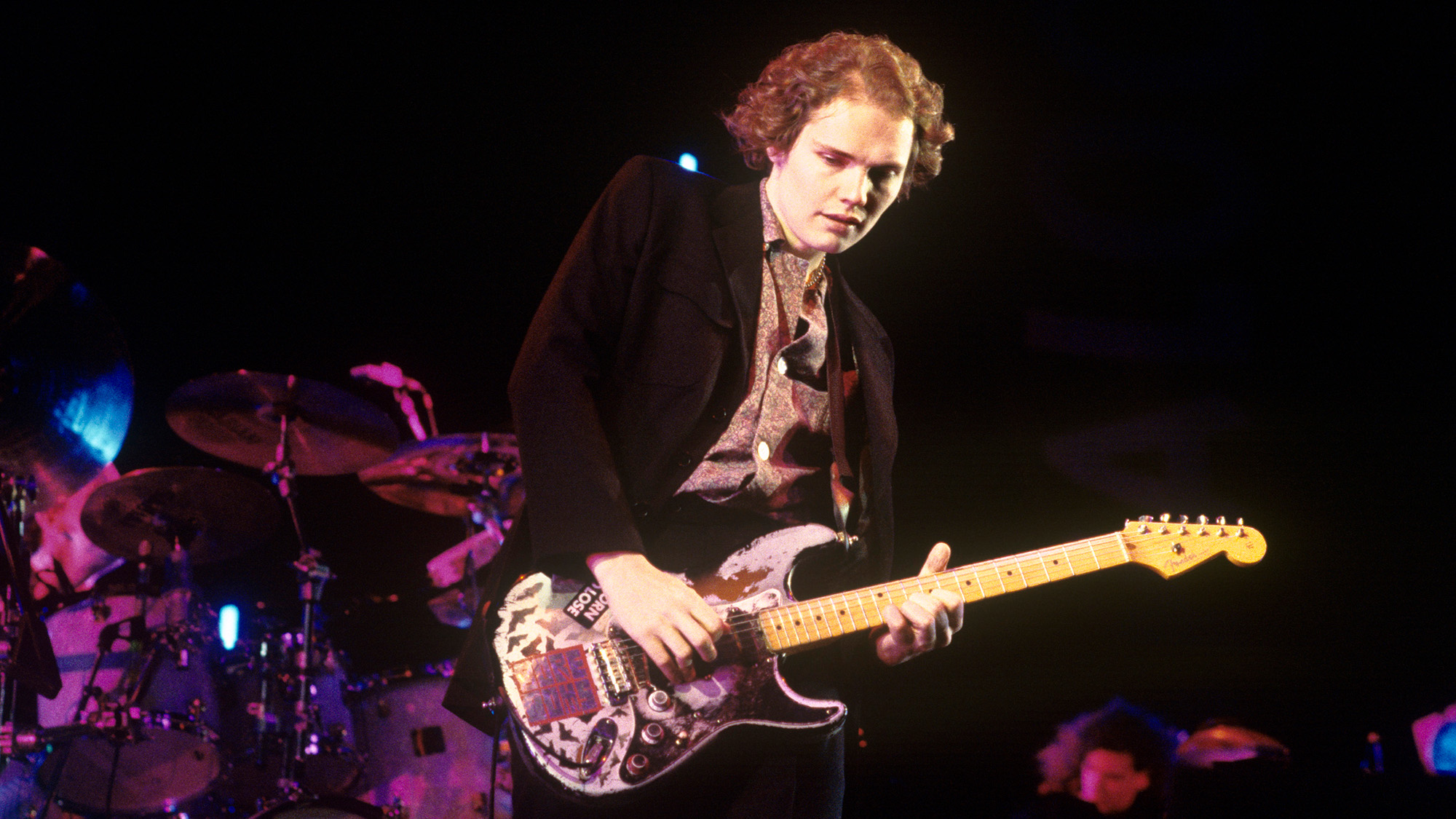

I learned a lot about rhythm guitar from listening to and watching Nile Rodgers and Prince play, and also chatting with Nile about rhythm guitar techniques.

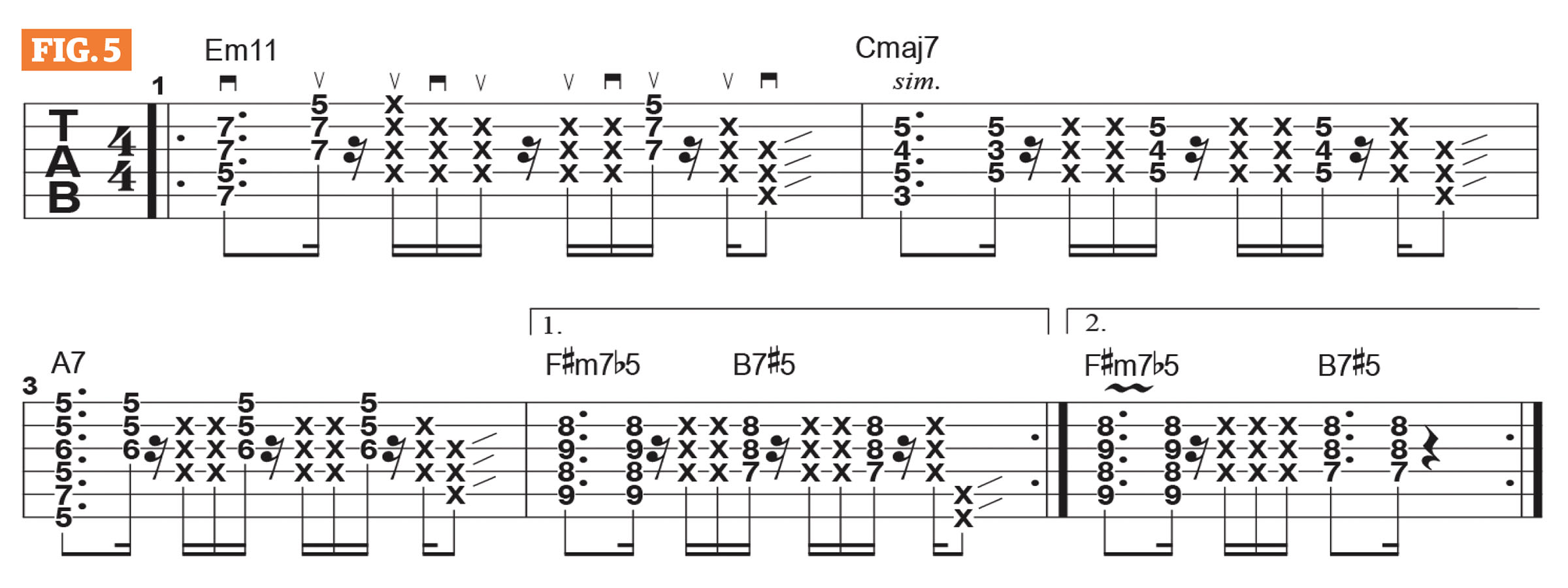

Figure 5 offers an example of a chord progression played in Rodgers’ rhythm style. For my tune Cosmic Sans, the main chord progression is Em11 - Cmaj7 - A7 - F#m7b5 - B7#5.

If I were to strum a full barre-chord voicing for each chord, it would feel too “chunky.” Instead, I do what Nile advised me to do – “Fret the whole chord form, but only sound parts of it at certain times, moving your right hand from the lower to the higher strings; that will add clarity and definition.”

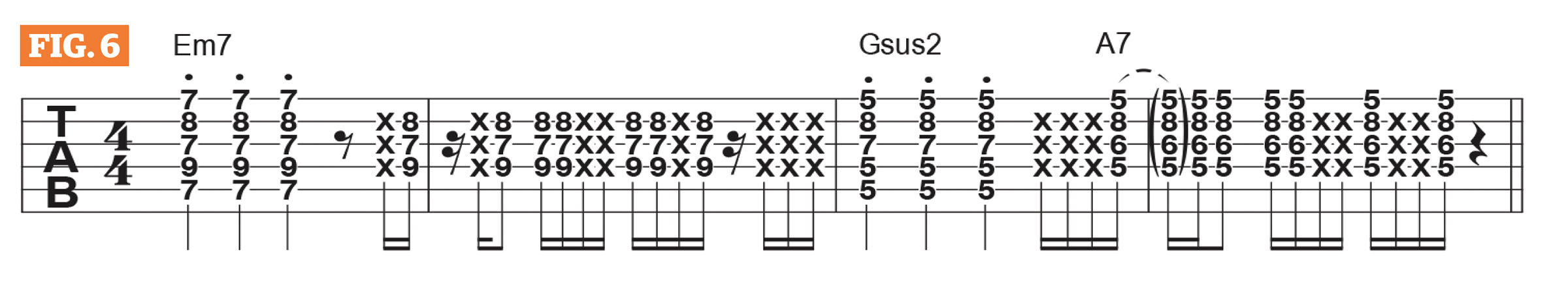

Nile will often move back and forth between full chords and smaller voicings, as in Figure 6. His tunes Good Times and Le Freak are great examples of this.

- This article first appeared in Guitar World. Subscribe and save.

Funk, rock and jazz pro Cory Wong has made a massive dent in the guitar scene since emerging in 2010. Along the way, he's released a slew of quality albums, either solo or with the Fearless Flyers, the latest of which are Starship Syncopation and The Fearless Flyers IV, both from 2024.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.