“The guitar was in horrible shape. The paint job was all flaked off, it didn’t have the original tailpiece... at one point, the headstock snapped off”: He's a hitmaker who owned Eric Clapton's “The Fool” SG, produced Meat Loaf, and played with Ringo Starr

He’s a multi-instrumentalist, songwriter, and producer who’s had his own hits and worked with such artists as Cheap Trick, Sean Cassidy, and Meat Loaf, but what Guitar World readers really want to know is…

A lot of what I’ve heard of your new album, Global, is heavily electronic, like your last album, State. Are you moving away from the guitar with your new music? – Craig Williams

“A lot of it depends on what kind of show I’m doing. When I play with Ringo’s All-Starrs, I get to play a lot of guitar for a good part of the year; it’s not lead guitar in that context, though.

“I guess it depends on how motivated I am to write songs with the guitar when it comes time to make an album. I think about what I need to do for a live performance and I tailor it to that presentation. This live show I’m currently doing doesn’t really involve a lot of other players, so I imagined myself as more of a frontman and singer rather than a guitarist.”

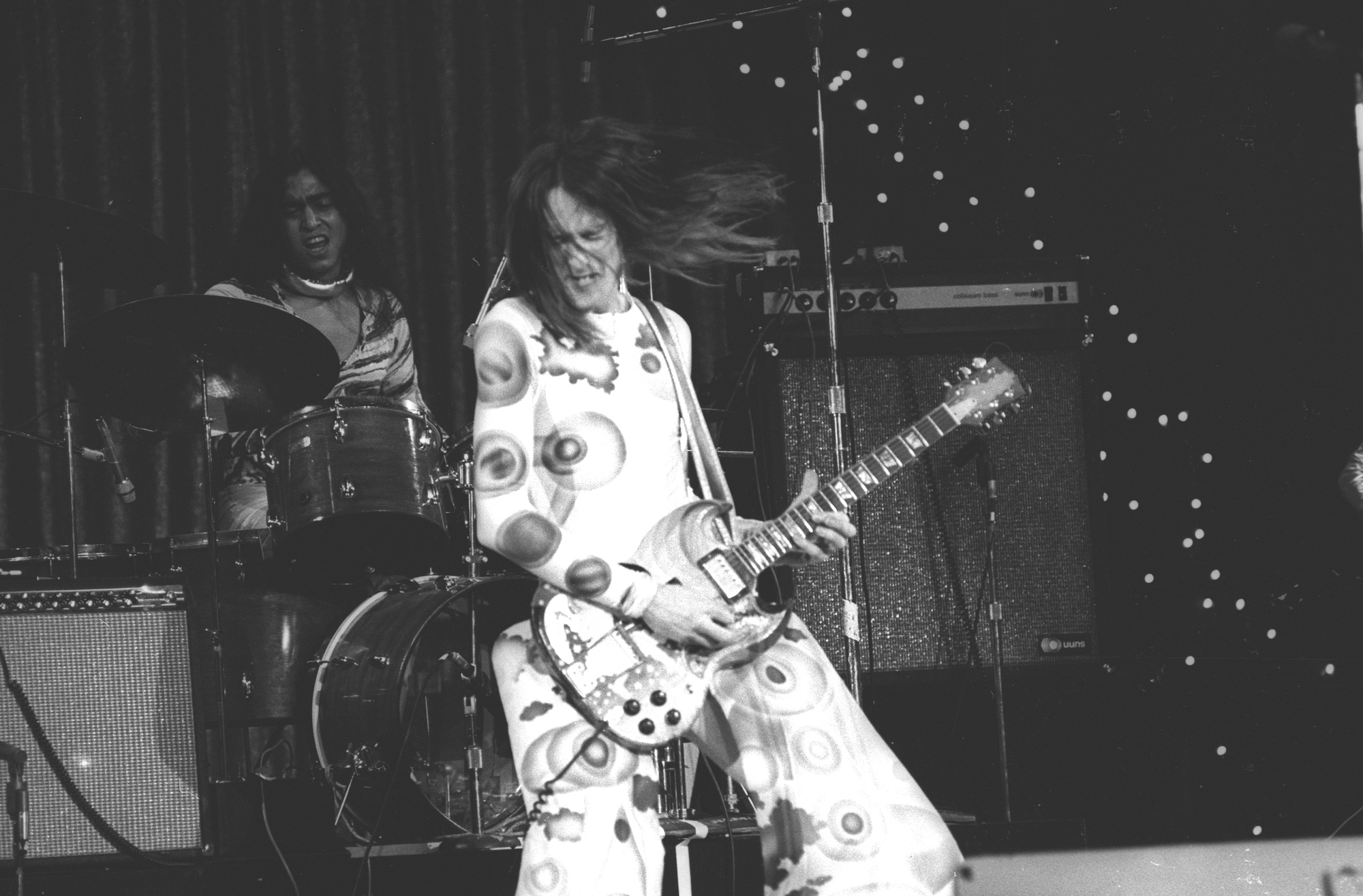

How did you come to own Eric Clapton’s psychedelic SG known as the Fool? Did he ever want to buy it back? – Norman Staller

“I have the feeling that Eric had given that guitar up, because it went through a number of hands before I got it. I think he gave it to George Harrison, and I’d heard that Paul Kossoff from Free owned it, too. I got it from Jackie Lomax, who was signed to Apple. This was when I was up in Woodstock working with the Band.

“The guitar was in horrible shape at the time. The paint job was all flaked off because they never put a sealer on it. It didn’t have the original tailpiece, the neck was a mess – at one point, the headstock snapped off.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I did a lot of work on it. I played it for decades, and I owned it until the mid-Nineties. I owed the IRS a lot of money, so I auctioned it off. But I did get to play it onstage with Ringo – with Jack Bruce, we did Sunshine of Your Love, which I thought was appropriate.”

What is your most prized guitar, and why? – Sally Foote

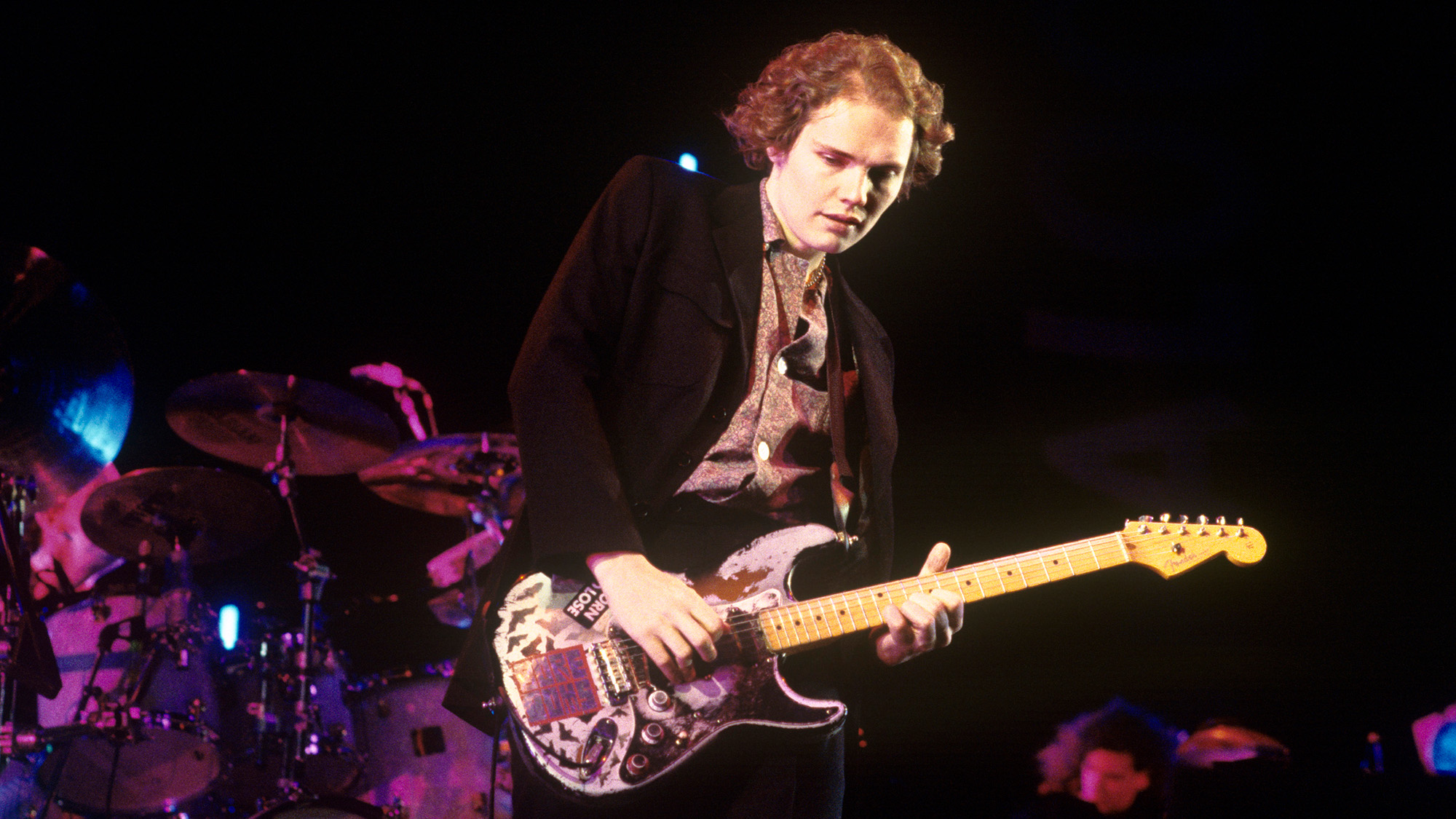

“I’ve put a lot of karma into Foamy, that green Fernandes guitar I’ve been seen with so often. It’s still my main guitar when I go out with Ringo. Whenever I do solos, or if I do something especially heavy or twinkly, I use that one. It gets a good range of sounds, particularly with my Line 6 equipment. I would miss that one if it disappeared.”

Your recent collaborative album with Hans-Peter Lindstrøm & Emil Nokolaisen, Runddans, was done by sending files back and forth between Hawaii and Oslo. Do you find spontaneity in that kind of arrangement? – “Big” Bob MacAdoo

“There is spontaneity because you’re not there to witness the evolution of music at the other end. This project went through so many versions and iterations, so I never knew what I was going to get. At one point, it was all one song that ran for an hour and a half.

“It was always interesting when I’d get something new, but sometimes it took months before that would happen. So it always felt fresh to jump in and contribute. I’d do my thing, send it back, and then a couple of months later, I’d get another version of something. You can’t help but feel spontaneity with a process like that.”

What makes you always want to try new stuff and keep pushing the envelope? Genre-wise, you seem to do it all. – Kevin Pasternak

“I bristle when people refer to me as a ‘rock star.’ I’m not a star; I’m a musician. Way back when, I wanted to know how music worked and how to play instruments. I started on the guitar, and as soon as I had access to a piano, I learned how to play that – and I went from there.

“Some people come to the realization that they want to get into music to live a certain lifestyle: They want to be in a band and play a certain kind of music, have fun, get paid, get laid – the musician’s lifestyle.

“My commitment to music was different. It’s what I wanted to do, and I knew that I wouldn’t be happy doing anything else. I suppose the continued exploration of that is simply because I get bored playing the same thing all the time. [laughs] Let’s change it up.”

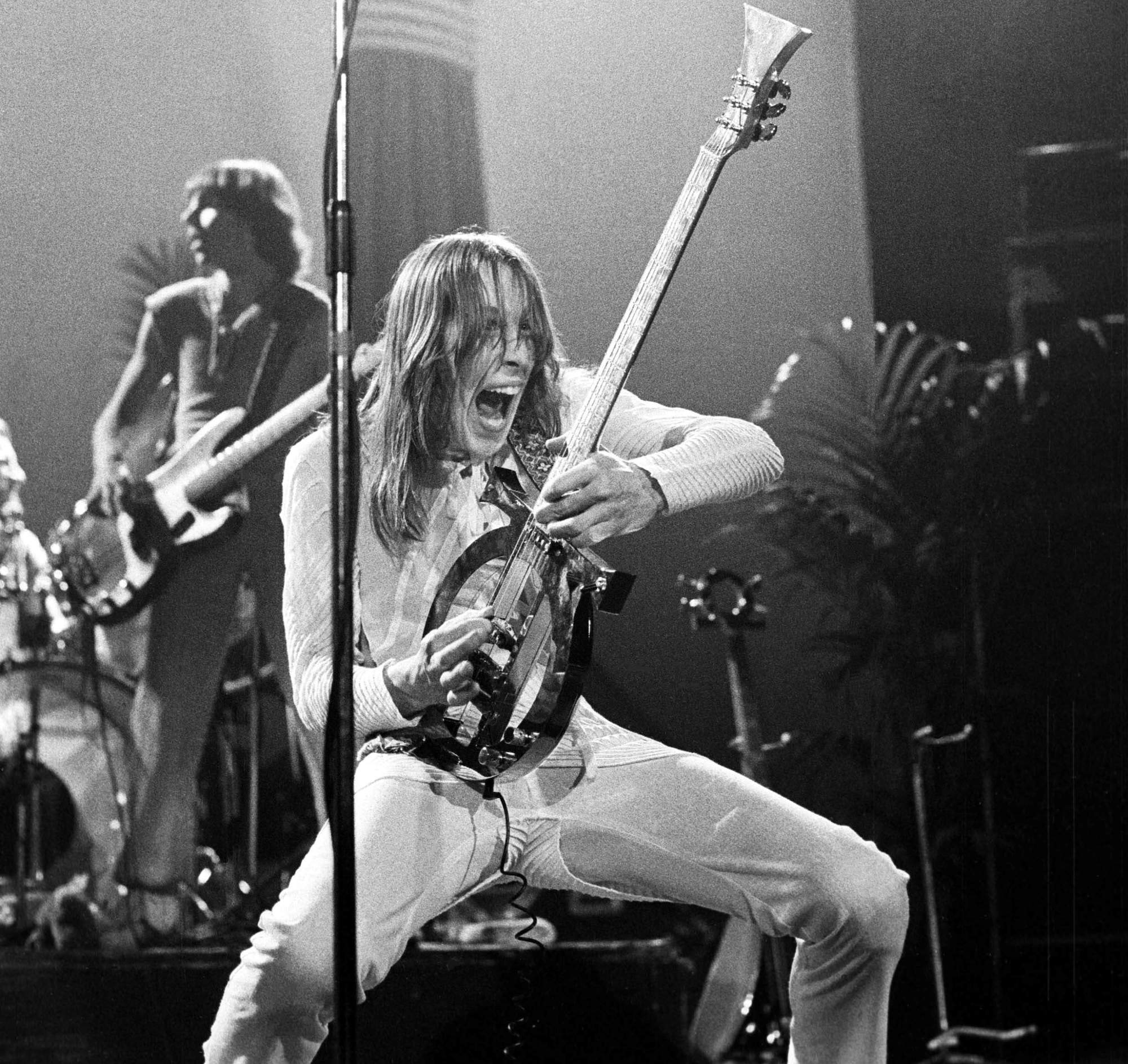

I saw a video on YouTube of you playing a fantastic guitar solo on the song Black Maria. How do you rate yourself as a soloist, and who were your inspirations, solo-wise? – Edie Sancore

“There was a time when I rated myself, but I was pretty young then. At a certain point, you realize that there are so many ways to play guitar and so many other great players out there, so it becomes a fool’s errand to put yourself in competition with everybody else. I just try to sound like myself.

“Everybody for a while patterned themselves after George Harrison, and so did I. He played such concise, accessible, and memorable solos that worked perfectly with any song.

“After I while, I started listening to the Yardbirds – they expanded the guitar solo in both length and character. Jeff Beck became my idol at that point. I wanted to play like him, which is another fool’s errand, because nobody plays like Jeff Beck.

“Then when I heard Eric Clapton with the Bluesbreakers, I said, ‘I wanna play like that guy, and if I can’t, I’ll kill myself.’ I tried and got technically close, but I got distracted by other players. I think, in the long run, I do something that’s derivative, but it’s sort of my own style.”

Some of your songs, like Bang on the Drum All Day and Hello, It’s Me, have been used for commercials and by sports teams. Have you ever heard a song of yours used in a certain way and went, “Ouch. I don’t like that”? – Hugh LaRose

“There was a time when I thought that the way I heard a song was the only way it was supposed to be. The Isley Brothers did a version of Hello, It’s Me, and at first I thought, ‘Wow, that’s weird.’ The more I heard it, I felt it was just as legitimate as mine.

“I’ve heard songs of mine and didn’t even know what they were at first. I was in a supermarket once and I heard Hal Ketchum’s version of I Saw the Light. I said, ‘I know that song, but that’s not me.’ It took me a minute to figure out what it was, a country version of my song. I like what other people do with my stuff – and, of course, there’s royalties.” [laughs]

I’ve always loved Utopia’s Beatles-influenced album Deface the Music. During any of your tours with Ringo, did he ever bring it up? – Michael Drewber

“I brought it up to him during the first tour I did with him, I think, in 1993. He seemed amused by the idea, but I don’t think he went out and listened to it. I’m not sure if he even listened to the Rutles [The Beatles parody band masterminded by Monty Python's Eric Idle].

“He gets assaulted with so much Beatles stuff, and I think he’s pretty tired of talking about it. I read the interview he did with Rolling Stone, and I think the interviewer was petrified to even bring up the Beatles.”

Is there anybody you would have liked to have produced, or is there anybody you still want to get in the studio with? – E.L. Ashton

“I’ve always felt that it was dangerous for the producer to take the lead in forming a relationship to make a record. It’s a big responsibility being in the producer’s chair, and sometimes you can be at odds with an artist. They want to do what they want, but sometimes you have other ideas about how to make their music better. So in that regard, I’d rather have an artist come to me and ask me to help instead of the other way around.

“That said, there have been some opportunities I wish I could have taken advantage of and some I wish could have come to fruition.

“The Talking Heads asked me to produce them, but I was already committed to the Tubes. They ended up hiring Brian Eno, which was kind of a turning point for them. I heard from Pete Thomas that I was on the list to produce Elvis Costello, and Pete Townshend told me that I was under consideration to produce the Who. I would’ve done those records in a second.”

I love your production of Grand Funk’s We’re An American Band, but please tell me it wasn’t your idea for them to pose nude on the inside sleeve of the album. – Bobbi Fenton

“Did they do that? [laughs] Wow, Okay. I wasn’t in charge of the packaging; in fact, that was all done before I even got involved. The management team and Lynn Goldsmith, the photographer, were in charge of building the band’s image. All of that stuff had to be done long before we even went into the studio. So no, I can’t claim any credit for that one.”

Knowing what you know now, what advice would you give to your younger self just starting out in the Sixties? – Danny Dameo

“‘Don’t take it all so seriously. Everything’s gonna work out.’ But maybe the fact that I took it seriously is why it worked out. You know, I got lucky, and you can’t advise against luck. I was in a certain point at the right time, doing the right thing. We couldn’t capitalize on it the way we wanted, but it did take me from amateur to professional status.

“What I did was, I never waited for something to happen – I just went out and did it. I didn’t wait for acclaim or affirmation or anything like that. I always kept myself busy and wrote music.

“Some people think that success only comes through the front door, so they’re waiting at that door. Truth is, sometimes it comes in the back door, so don’t worry about it. Just keep busy and do what you’re meant to do. If you do that, it’ll all come together.”

This feature was originally published in the August 2015 issue of Guitar World.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.