“People were saying, ‘You’re not gonna make it.’ We just kept going. It took us six years”: The Smithereens’ Jim Babjak on how they went from broke to touring with Tom Petty – and became Kurt Cobain’s tonal reference for Nevermind

It’s only taken 45 years for the Smithereens to have hit the big time. Yes, they’ve bagged gold records and have toured the world, but recently they’ve hit what is surely the pinnacle of success with the propagation of Smithereens tribute bands.

There’s Broken Pieces, Blood & Roses and Dead Äire, among others, and if the trend continues, guitarist Jim Babjak just might get in on the act. “I was joking to my manager, ‘These tribute bands are probably making more money than me,’” he says. “Maybe I should form a Smithereens tribute group and be in it.”

He might have a hard time with that, as the actual Smithereens’ touring dance card has been full as of late. That the band is performing at all is something of a miracle, as many assumed that the untimely passing of lead singer and songwriter Pat DiNizio in 2017 spelled the end of the beloved New Jersey-based pop rockers.

“You get knocked down, but you’ve got to find ways to keep going,” says Babjak, who a year earlier suffered the loss of his wife to pancreatic cancer. “Before she died, she said to me, ‘You’ve got to live your best life.’ That struck a chord with me. The fact is, people still want to hear these songs, and I want to play them because I put my heart and soul into them.”

Babjak and drummer Dennis Diken, who formed the band with DiNizio in 1980, are usually joined on tour by co-founder and bassist Mike Mesaros, but occasionally the bass slot is occupied by onetime member Severo “The Thrilla” Jornacion or longtime Joe Jackson bassist Graham Maby.

Their frontman position is also a fluid situation. For the past few years, it’s alternated between Marshall Crenshaw and Gin Blossoms singer Robin Wilson, but recently John Cowsill (best known for his work as singer and drummer with the pre-Partridge Family band the Cowsills) has assumed the post.

“It all feels pretty natural now,” Babjak says. “Because Marshall plays dates on his own and Robin is busy with the Gin Blossoms, we needed a third guy. John Cowsill has been a friend for a long time, and he called us up and said, ‘Do you need a singer?’ And he was perfect.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“See, we know these people. After Pat died, people were telling us, ‘Listen to my tape. I sound just like Pat.’ That was creepy to me. Playing with people we know, it’s more like the band is just continuing with the same heart and soul we grew up with.”

For Babjak, whose tough and tuneful ways with riffs and solos have fueled a fleet of three-minute corkers like A Girl Like You and Sorry, working with Diken is a constant source of inspiration.

“Every time I get on stage with him, I think, ‘This is what I live for,’” he says. “We feed off each other, and I benefit so much from the exchange. When I met Dennis, he was drumming like a pro – he could play like Keith Moon. I was just trying to keep up with him. But that’s the secret. I tell young people all the time, ‘If you’re forming a band, work with musicians who are better than you. They’ll make you better.”

When I met Dennis, he was drumming like a pro – he could play like Keith Moon. I was just trying to keep up with him

You, Dennis and Mike were already playing together when you guys hooked up with Pat. Did you know right away that he was the guy?

“Oh yeah. We fit right in with Pat. We were looking for a lead singer who could write songs. I was trying to write, but I wasn’t good at the time. We tried a few singers before we met Pat, but when we found him, it was all right there. We got a singer, and he got a band ready to go.”

Did it take some time for you and Pat to get your guitar sound together?

“That’s the thing; we didn’t really talk about it – it just happened. His demos were very basic, so I would try to fill the songs out and do interesting things. For instance, Blood and Roses has a C chord, but I would lift my index finger on the B string. I don’t know what that’s called – I just knew it sounded good. My forte was coming up with opening riffs and solos. When I played chords, I’d try to play differently from Pat, whether it was strumming or picking.”

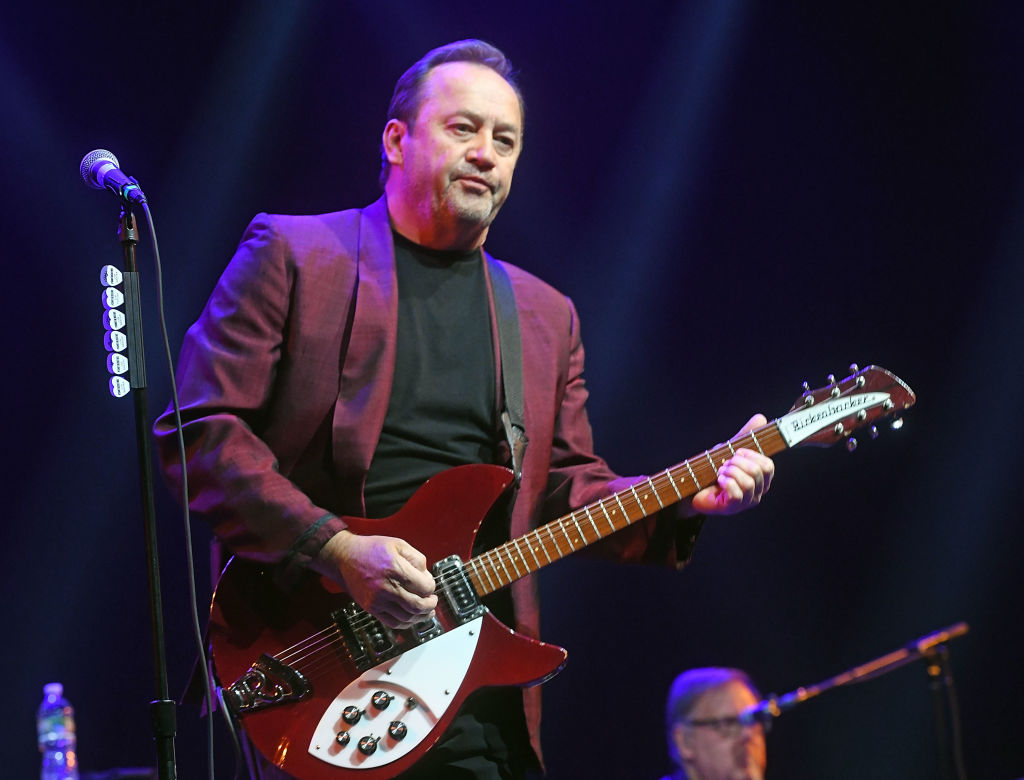

How did you come to pair your Rickenbackers and Telecasters with Marshall amps?

“Actually, I was using a Music Man early on. My brother, who’s seven years younger than me, bought a Marshall JCM800 100-watt head. I plugged into that thing and was like, ‘I’m keeping this.’ Ever since 1983, I’ve been using the Marshall, and it’s become my sound. It’s got perfect feedback that I can control.”

Given your love of Pete Townshend, I would think you might have tried Hiwatt amps.

“I never had the money. That Marshall of my brother’s? I had to trade him a ’71 Strat and my original Rickenbacker 12-string.”

Pat played mainly Strats and Jazzmasters…

“That’s right. He put those through a Mesa Boogie.”

You called Pat’s demos “basic.” How much so?

“They were pretty basic. Sometimes he’d play a song live. At this point, we were rehearsing in his basement with no PA. With some songs, we didn’t know what the words would be. He’d have a title, but he would wait until the last minute to finish the lyrics. One thing I always liked: If a song sounded happy and jangly, the lyrics would be depressing. I thought that made the songs unique.”

You guys played your fair share of New Jersey dives. There was the Dirt Club in Bloomfield…

I kept telling myself we’d make it, but in my heart I thought we wouldn’t. Things got very tough

“Yeah, I used to love that place. The owner’s wife kicked us out – twice. She thought we were too loud, and she didn’t like Pat’s voice. But there were some cool bands that played the Dirt Club. I remember the Catholic Girls got signed, and we were like, ‘Oh, cool! That means the Dirt Club is on the radar.’

“Of course, nothing happened with us. We didn’t give up, though. I didn’t get a job so I could devote my time to the band. I got some insurance money after my car got stolen, so I used that to open a record store. That way, I could be my own boss and do whatever I needed to stay in the band. Dennis and I opened a T-shirt store, which I let him keep.

“He was his own boss, too. Mike and Pat both lived at home. We were lucky to have the time to keep pursuing a stupid dream even though people were saying, ‘You’re not gonna make it.’ We just kept going. It took us six years to get anywhere.”

Were there times, though, when you thought, “We’re not gonna make it”?

“I kept telling myself we’d make it, but in my heart I thought we wouldn’t. Things got very tough. But then we recorded five songs on a low budget – we knew the engineer at the Record Plant, and he snuck us in after midnight – and we sent tapes around. All the major labels turned us down, but there was a small label in California, Enigma; they liked us and signed us. They put us together with Don Dixon, and we recorded the other six songs for $5,000.”

That was the 1986 album, Especially for You.

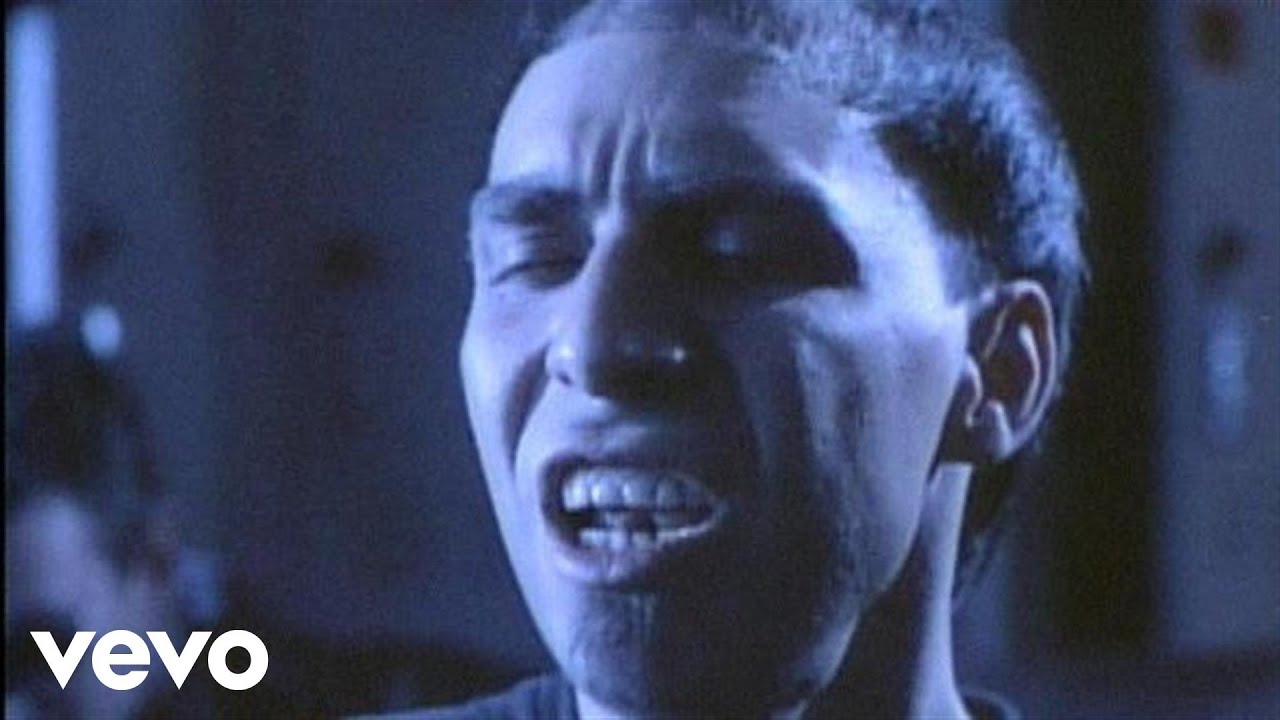

“Yeah. I thought it was good, but I didn’t think that many people would like it. I never thought Blood and Roses was a single. We buried it on the second side as an album cut. Then it got in a movie and our video got on MTV. Scott Muni at WNEW started playing it, and then other radio stations picked up on it. Suddenly, it was like, “Holy shit, people like this!”

What was it like when you guys realized you had finally made it?

“It didn’t happen for a while, and it kind of happened over time. You hear this from a lot of bands when they start selling records: I didn’t see any money from it. I remember at one point I was living in an apartment and we were opening for the Pretenders – three nights at Radio City. A guy living upstairs from me looked outside and saw me with a guitar case that said ‘Smithereens’ on it.

“He was surprised that I lived there. But opening acts would get, like, $500. Slowly, our price went up, but we were still traveling in a van. On the tour for Green Thoughts [1988], we got a Winnebago, and that seemed kind of dangerous. We didn’t get a bus until halfway through that tour.

“Most of the money I’ve earned has been from the road. We made videos that cost a fortune; each time we did one, it was $50,000 to $100,000, and of course, it all got charged back to us. We made some great videos that didn’t get much play on MTV.

“o yes, we made it in a way, but our gratification came from the audiences at the shows. We’re used to not getting noticed. I remember 11 [1989] sold a lot – A Girl Like You was on it. I’d pick up Rolling Stone and go to the concert listings, and we were never in it. I’ve lived with being under the radar all my life. Fuck it.”

Don Dixon and Ed Stasium are two of the more notable producers you’ve worked with. What are their differences when it comes to recording guitars?

“With Don, our albums sounded a bit more jangly; he might have sweetened us up a bit. Ed sweetened us up, too, but not as much. I think we were trying for a heavier sound with Ed. I remember when we recorded A Girl Like You, he had me play the riff eight times, and he said it had to be exactly the same each time.”

Of the cover albums the band has done, Meet the Smithereens! and The Smithereens Play Tommy are beautifully played and recorded. Tommy is a strikingly clean recording.

“Those records were done at the House of Vibes in [Highland Park] New Jersey; Kurt Reil [of New Jersey band the Grip Weeds] engineered and co-produced it with us. Pat didn’t play guitar on those; I did all the guitar work.

“On the Tommy album, I used a Les Paul with P90s that I borrowed from Kurt’s wife, Kristen. I wanted to keep it simple and use only one guitar, make it more Live at Leeds. I played bass on Tommy Can You Hear Me? That’s me playing a Hofner with a pick.”

Did you hear from either Paul McCartney or Pete Townshend?

“No, no, no… I once had an opportunity to meet Pete Townshend. We were rehearsing at SIR in New York, and he was in the next studio with the people from the Tommy play. My guitar tech ran in and said, ‘Hey, you want to meet Pete?’ I was too scared. I heard he could be a real curmudgeon so I didn’t want to ruin it.”

You mentioned being under the radar, but a lot of people were paying attention. It’s been said that Kurt Cobain cited the Smithereens’ sound when Nirvana was cutting Nevermind.

“Butch Vig told me about that. Before Capitol dropped us, they had us do Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer for a Christmas sampler. We were thinking of using Butch for our next album – which never happened – so we hired him to do the Christmas song. He told us about how they would be in the studio A/B-ing my guitar sound; they were trying to get these production ideas and stuff. I thought that was really cool.”

Another big fan was Tom Petty, who in 2013 selected the Smithereens to open for him and the Heartbreakers.

“Oh, man, that was so cool. I saw him in the hallway at one of the shows we were opening for him, and I actually asked him, ‘Did you really ask us to be on this leg of the tour, or is that bullshit?’ And he said, ‘No, man. I love you guys.’ He had heard our song Sorry, and he loved it. He said, ‘I wanted you guys on the tour.’

“I was like, ‘Thank you!’ Suddenly, I was talking to him about Del Shannon – we were friends with him. It’s sad I didn’t get more time to talk with Tom. People were coming up and doing photos – that sort of thing. And then, of course, he passed away. God, what a great songwriter he was.”

When Pat started to experience health problems, did the band ever talk about breaking up?

“No, never. Pat couldn’t play guitar anymore, so we functioned as a three piece. In a way, it harkened back to the Live at Leeds thing Dennis and Mike and I did. Mike came back for a good solid two years, and the band sounded great. Pat’s voice was great, too. He was a fighter. He’d been sick for five years – it was a slow decline.

“He could sing up to the last day of his life. We were even trying to work on new material. The last show we did, he had to sit in a chair, and that was really sad. After that, we thought, ‘We need to take a break and assess the situation.’ He died soon after. There wasn’t much of a gap between that and us continuing.”

The band is working on a new album. What can we expect?

“Dennis and I laid down maybe six tracks, but I’ve got about 20. He’s got some ideas, too. I have some songs earmarked for Marshall to sing and some for Robin to sing. If they want to contribute a verse or a bridge or something, they can, and we’ll go from there. I don’t want to rush it or put a deadline on it.

“The other thing is, we have another 14 songs or so with Pat that were unfinished. He’s singing and playing acoustic guitar on them. They’re really good demos; they’re not really finished, but they have full lyrics. There’s drums on them, and last year Mike put bass on them. I’m on them, too. There won’t be any AI involved; it’s just us. It’s going to be another ‘lost’-type record. I’m really looking forward to it.”

- This article first appeared in Guitar World. Subscribe and save.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.