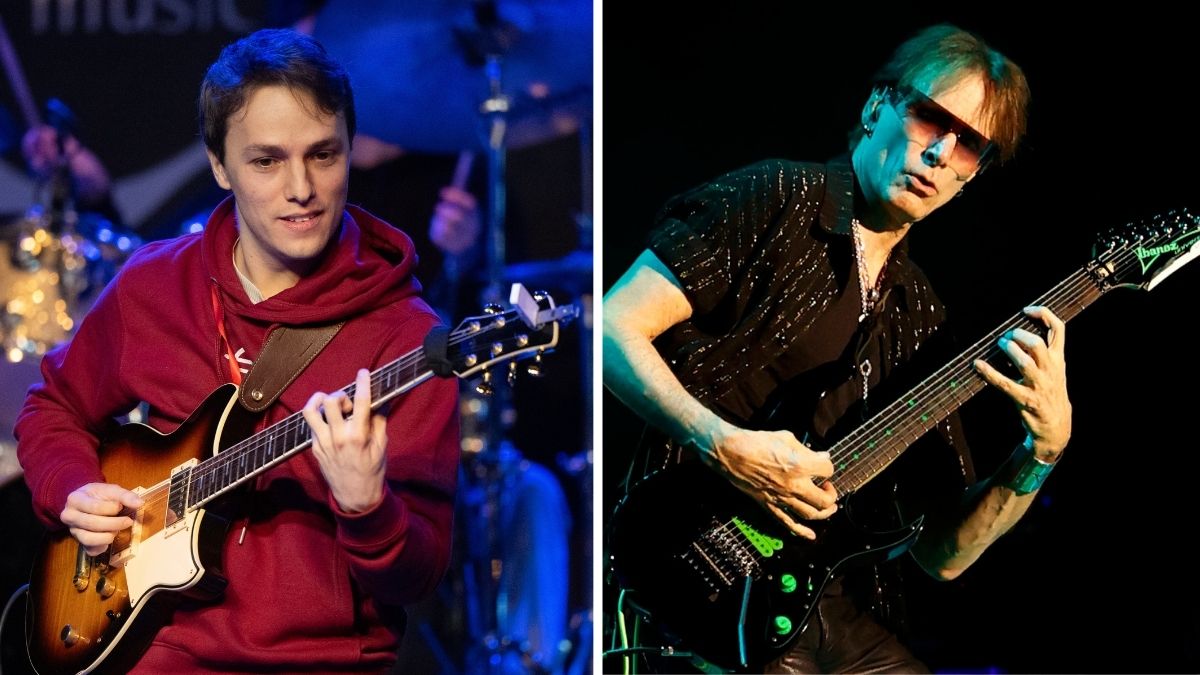

“I always played B.B. King. His style was commercial, not like the gutbucket style”: You may not know his name, but Jimmy Johnson was a contemporary of Buddy Guy – and the ultimate example of a Chicago blues virtuoso who ventured well outside the box

Brother of acclaimed guitarist Syl Johnson, the late Jimmy Johnson was a singular player who was a mainstay of his city's legendary blues scene, and wowed onstage into his 90s

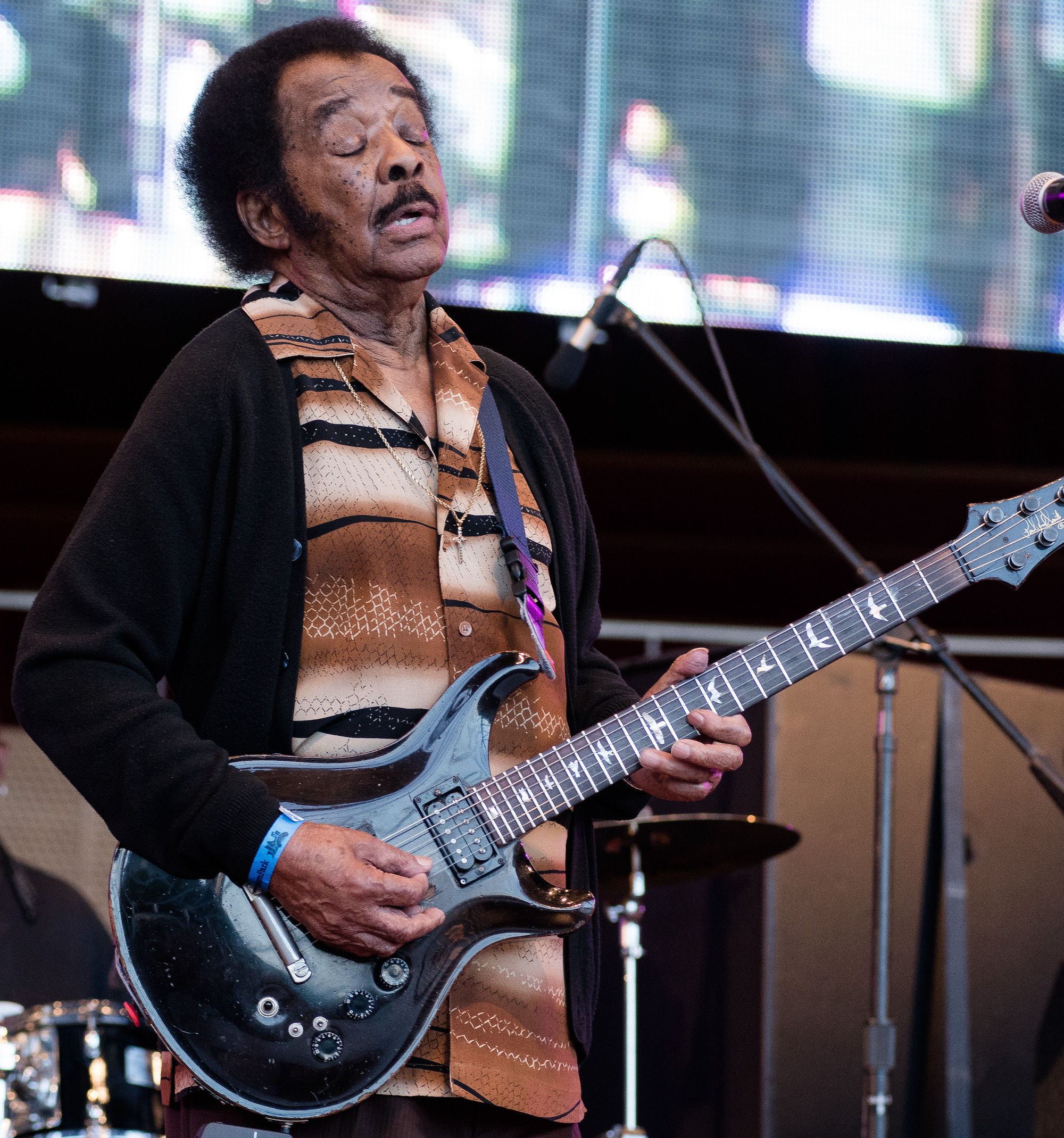

Chicago blues guitarist Jimmy Johnson is one of a rare species threatened with extinction.

As we move torridly into the 80's with the newer, younger voices in rock exploring the roots of their music and simplifying their presentations, Jimmy Johnson serves as a vibrant link to the past.

His music is a direct extension of the basic blues tradition that godfathered rock. Johnson serves the role especially well; he is old enough to have been there when the golden age of blues was happening, and is young enough to keep it happening.

Chicago is a town that oozes great blues. During the '40s and throughout the '50s, Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Jimmy Reed, Chuck Berry, and B.B. King all made their names in the Midwestern capital. If one place had a pivotal position in the birth and dissemination of rock, it was Chicago.

Today, the Chicago blues scene remains healthy.

Dotting the city are dozens of clubs that cater to the various audiences that exist and the even greater variety of blues stylists that the city produces. In Chicago, you can find many of the elder statesmen still getting down, plus a new breed of strong players.

Jimmy Johnson is curiously in between. He is 51 years of age, but as he says, “I have a body like a 35-year-old.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

He is one of a handful of blues artists to come along in the last decade and develop a national reputation, along with Albert Collins, Luther Allison, and Son Seals.

The small national audience that exists for the blues these days is monopolized by legendary players like Muddy Waters and B.B. King.

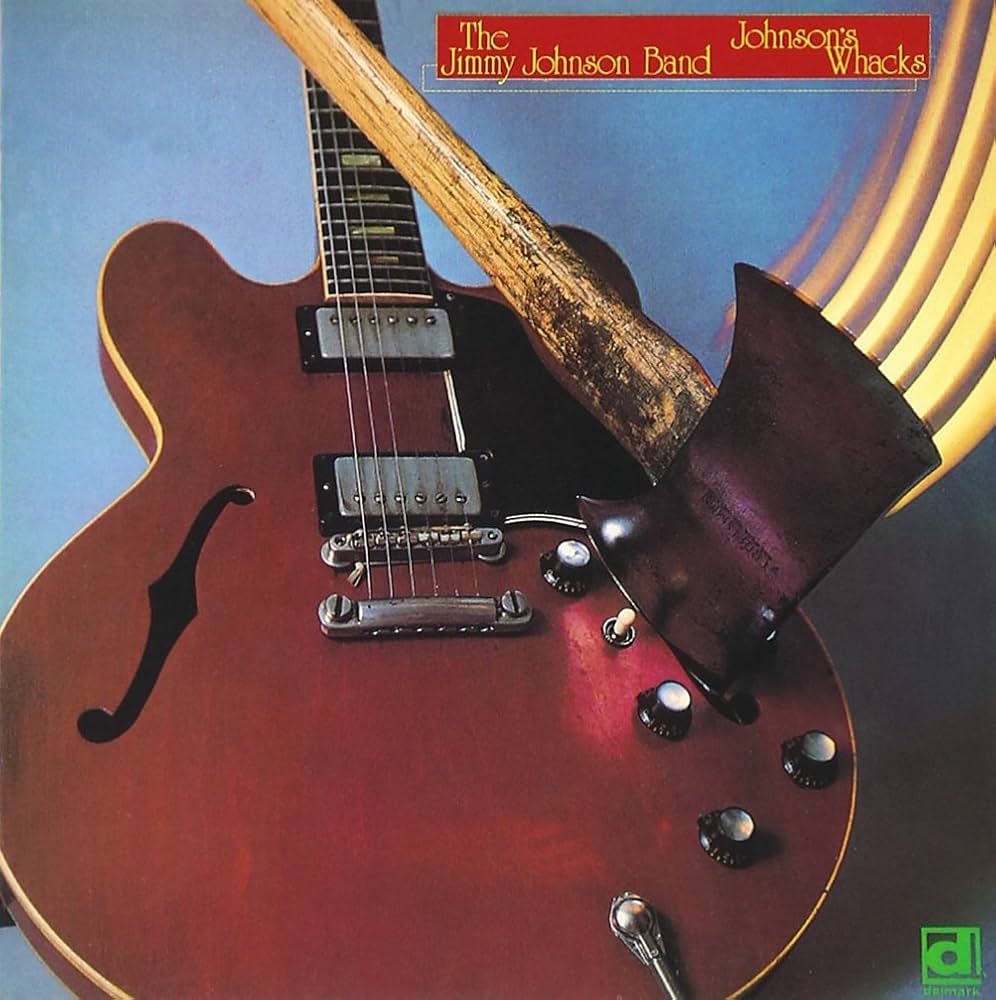

Jimmy Johnson's first solo American album, Johnson's Whacks, recently caught my attention. I can't exactly say why, but when Johnson's Whacks hit the turntable, my bedroom began to jump, and my sneakers took a fateful turn toward destruction.

Johnson's Whacks is an infectious mixture of blues styles. Jimmy Johnson goes from a slow ballad style blues to an uptown shuffle version of Dave Brubeck's Take Five.

When Jimmy came to New York recently, he and I sat down to talk in a tacky luncheonette which served marvelously as the backdrop for the tale of blues I heard that day.

Jimmy Johnson never started out to be a musician.

“Clear through my twenties,” he told me, “I didn't pay no attention to music. You see, when you're a young cat, the main thing that you want is a set of wheels.

“I had a good gig when I was in my twenties. I was making like 60-70 dollars a week, which at the time was a lot of money. I would buy convertibles and deck them out; spare tire on the back, drop down behind, spotlights, and all sorts of shit. That's what I was into, and chasing a lot of girls. I didn't think about no music.”

That was in the early '50s, when he had moved from the South where he was born, raised, and spent his teens flirting with women and poverty.

Holly Springs, Mississippi was home for Jimmy then. He worked beginning at an early age along with his family in a situation that essentially was an extension of sharecropping.

“Milkin' cows, raisin' cotton, corn, peas, potatoes, and all kinds of stuff like that. I was really pickin' cotton. It wasn't no joke. I was farming everyday from ‘kin till kan't,’ from when you can see until you can't.”

“We were kind of poor. My father left us [eight children] when most of us were still young and unable to work. It was hard on my mother, but she was always there to teach me right from wrong. Now me being a kid, I didn't know any different, but living in poverty was a pain in the ass.

“I don't want to step on anybody's toes, but some of the white men down there at the time didn't care about you, and they would be beating you. You live on this white man's land and you would pay him so much for the rent for the house. They would take that out from whatever you raised.

“He didn't care about you going to school either. All he wanted you to do was work. As a matter of fact, they would say that it was better if you didn't go to school.

When my uncle would turn his back, I would play some blues. He wouldn't have that kind of music in his house

“The government made schools for us, but I had a hard time going. I had to walk maybe four or five miles a day to go, and I really didn't have sufficient clothes to wear. I finished school, though, because I knew I had to. I knew that you had to know something.”

Still in his teens, Jimmy made the big jump. He moved on from Holly Springs, first off to Memphis, where work was hard to find, and then on to Chicago, where things began to pick up.

“I worked in a sheet metal factory where you make stuff like kitchen cabinets, hot water heaters, desks, tables, things like that. I worked there until 1959, which is when I started playing professionally.”

Jimmy's musical abilities did not appear by magic in 1959. They had been an integral part of his life. He just never had taken a disciplined approach to his talents. Music came naturally.

“When I was going to high school, I started playing the piano. When we would have recess for an hour, instead of going outside and playing with the rest of the kids, I would go upstairs in the auditorium where there was a piano on the stage behind the curtains. I would go behind there and play.

“When I came up to Chicago I continued to play. I lived with my uncle, who was a preacher. We lived above his church, which had a piano in it. I would go down to the church and play on that piano. I got to know the notes and some fingering. I would play for the Junior Choir and things like that. I always loved music.

“When my uncle would turn his back, I would play some blues. He wouldn't have that kind of music in his house. The blues and soul ain't nothin' but gospel. Blues, though, was dirty music. In gospel, you're singing about God. It's often the same melody, but in blues you're singing about your woman.”

I wondered what music Jimmy had been listening to up until this point.

“You never went out and bought a record,” he said. “A record was a rare thing. If you found someone that had a record player, you were lucky.

“I remember knowing someone that had a wind-up Victrola, and I used to hear Louis Jordan, Sonny Boy Williams, Arthur 'Big Boy' Crudup, John Lee Hooker, and then Muddy Waters and B.B. King.”

The imposing Chicago blues scene soon made its way into Jimmy's life.

“In the late 50's I first started listening to music, because I started meeting all these cats. I met Junior Wells and Buddy Guy, John Lee Hooker, and Otis Rush. These were good musicians, and it began to dawn on me what music was all about.”

If you learn music, harmony, and theory, it's much easier to play anything that you want to play. There are some famous cats who can't play those different kinds of things because they don't know anything but their own sound

At the same time, two of Jimmy's younger brothers were playing regularly. His brother Syl played guitar and sang with Junior Wells. He appears on some of Wells' recordings of the 50's. Jimmy's brother Mac played bass and appeared often with Magic Sam.

“Magic Sam lived next door to us. He was a young kid, about 14 or 15. He had an old guitar that he played and he began to do little gigs and stuff. I'd go see Sam play and it looked like so much fun. I said to myself, ‘Man! I can do that,’ but there were no gigs for piano players.

“I knew that the guitar was the quickest way up. Everybody wanted to hear the guitar. It was big time music, the guitar and the harp. People would always come out to hear a good singer, too.

“I was a good singer, and that helped me to do so well so fast. People liked to hear me sing, and if I couldn't play something when I was first starting out I could always sing it.”

Jimmy Johnson's ambition led him to a couple of guitar teachers with the hope of solidifying the success he had right off.

“I went to a school for a while to learn music. It was called the Boston School of Music. I wanted to learn the real way of playing the guitar instead of just banging the blues. I went there for about eight or nine months, but I really didn't like what the cat was teaching me.

“I then started going to this cat named Reginald Boyd. He did a lot on the Chess label and you see his name all over the place on that label. He started teaching me like jazz kind of stuff, which is what I wanted to do. I went to him for a couple of years. He would teach me how to make chords and which note goes with which note.

“If you want to play music, you can play a lot of bad sounding things if you don't know what note to play when. If you learn music, harmony, and theory, it's much easier to play anything that you want to play. There are some famous cats who can't play those different kinds of things because they don't know anything but their own sound.”

Jimmy clearly respects musicians who are versatile. He especially admires jazz musicians.

His version of Dave Brubeck's Take Five on the Johnson's Whacks album represents an attempt to play jazz. It misses some of the melodic and rhythmic inflections that were part of the early 60's original, but there is something about Jimmy's version that is even more electrifying than that classic take. Jimmy's version is unabashedly soulful.

Johnson confesses, “I really like jazz but I am not good enough to make a living at playing jazz. If I was a real good jazz cat I would be happy doing that.

“On our record we play Take Five, but I know that ain't up there with those cats. But there is a lot of feeling in blues so I like to play that. Your soul can be revealed in blues. I wouldn't be happy playing R&B or disco. I would feel like a dog doing that.”

Jimmy speaks his feelings for the blues. “It will never go. It's the beginnings of Black music – that along with gospel.

“It's the truth, the people's music. Its place as the original will never go. Blues came before jazz. You see rock and soul, it all came from the blues and when you look at it, it ain't nothin' but hopped up blues. There are different directions, but it will always be the blues.”

When Jimmy first began playing as a professional in Chicago, it was his meal ticket. The blues, however, has many shades to it, and Jimmy offers a feeling for the many styles that exist and their place in the Chicago club scene around the time he was starting out.

“I would always play B.B. King. His style had always been commercial, not like the gutbucket style. I would never play Muddy Waters, that's a different thing altogether – Muddy Waters, Jimmy Reed, Little Walter, and Elmore James.”

“We had never heard of Albert King up until that point. He came out in the mid-60's. Today, I still don't do that real down home blues. I practice it a lot because I want to get that feeling. Well, I'm just greedy though, I want to learn to play anything.”

The word “greedy” really hits you in the heart. The man is anything but. Although he spent so much of his youth toiling for survival, and as a man in his middle years is conscious of the relative exclusion of blues artists from the profits of commercial music, Jimmy Johnson seems content.

“What makes all those rock people make all that money, it's promotion. The man on the radio says what is hip, and you don't want to be no square, so you go out and buy it. Blues, I don't think, will ever sell five million copies like a rock record, but I have no hostile feelings for nobody.”

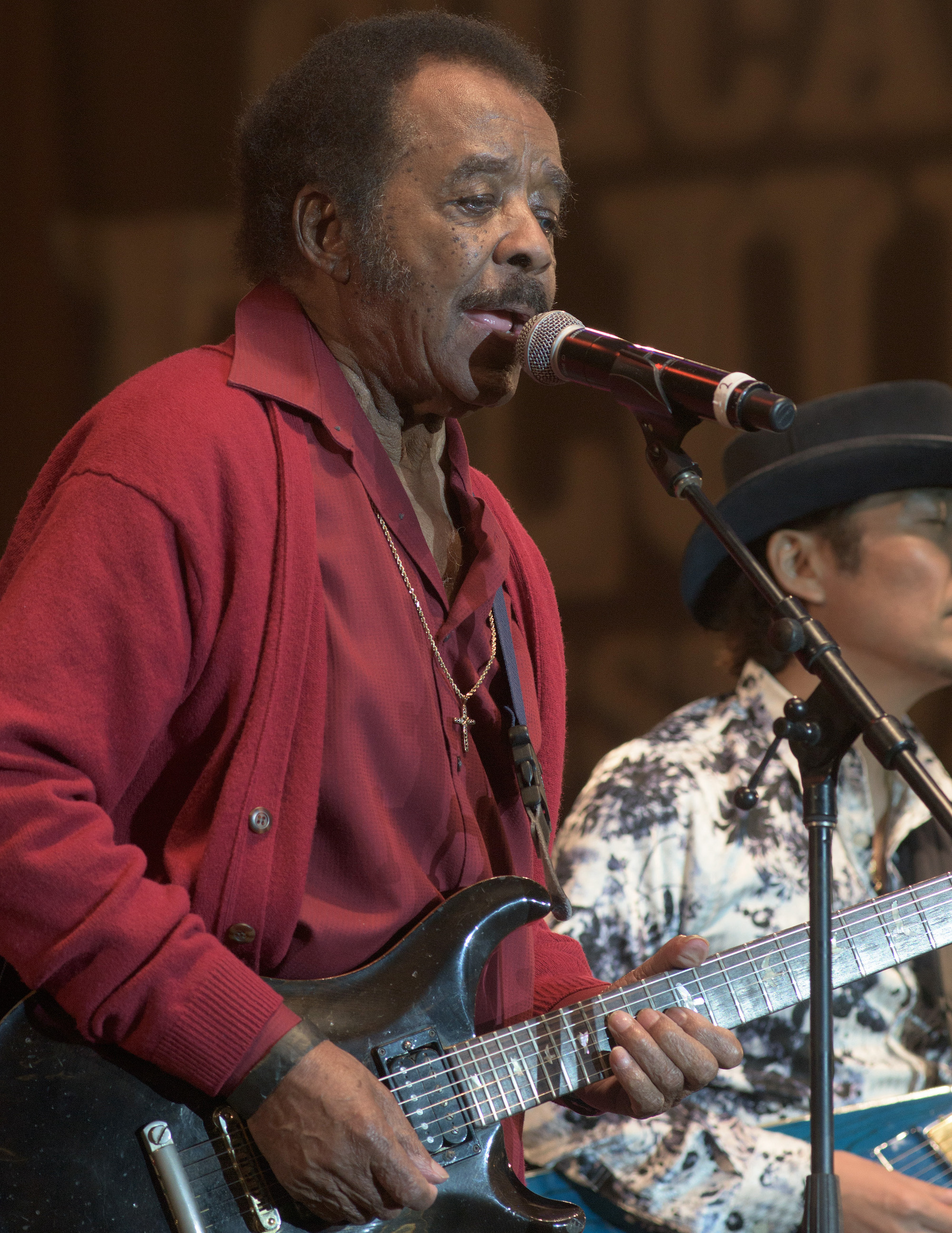

Today, Jimmy shows the same passion for his guitars that he once lavished on cars.

“I got a new guitar now. It's a Gibson model 347. It's got a neck like a 335, a fine-tuning bridge, and a stock tail piece. I have a bypass switch on it so I can cut the humbuckers off and make it sound like a Fender. I have a master volume switch on it, too. I need that for controlling things while I am singing and moving between pickups.

“The 335 you see on the album cover is in the shop now. The frets got all worn down to the neck. I couldn't play it anymore.”

“I have always used Fender amps and still own a Super Reverb, but now I'm using a Music Man amp. I think they are the best now.”

As we reached the present tense in our conversation, it was time to get on to that night's gig at the club Tramps. Jimmy and the rest of the band were happy to pile into my van (no seats) for the short ride down from the hotel to the club.

I was psyched for the show and was in no way disappointed. Jimmy's steaming band and his stinging lines had the crowd screaming.

One story Jimmy told me that day stuck in my mind. It seemed incongruous with the subtle pride this man exuded. It seems as though Jimmy's real last name is Thompson, but that on a recording his brother Syl had made for Bee-Hive records (in the early 60's) they printed his brother's name, mistakenly, as Johnson.

At the same time, Jimmy had always been known as Syl's brother, and as more and more people called his brother Syl Johnson because of that record, Jimmy became Jimmy Johnson.

I asked him why he didn't correct people and maintain his original name. Jimmy replied, “What's the difference, you ain't nobody anyway.”

- This interview with Jimmy Johnson first appeared in the September 1980 issue of Guitar World. Subscribe and save.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.