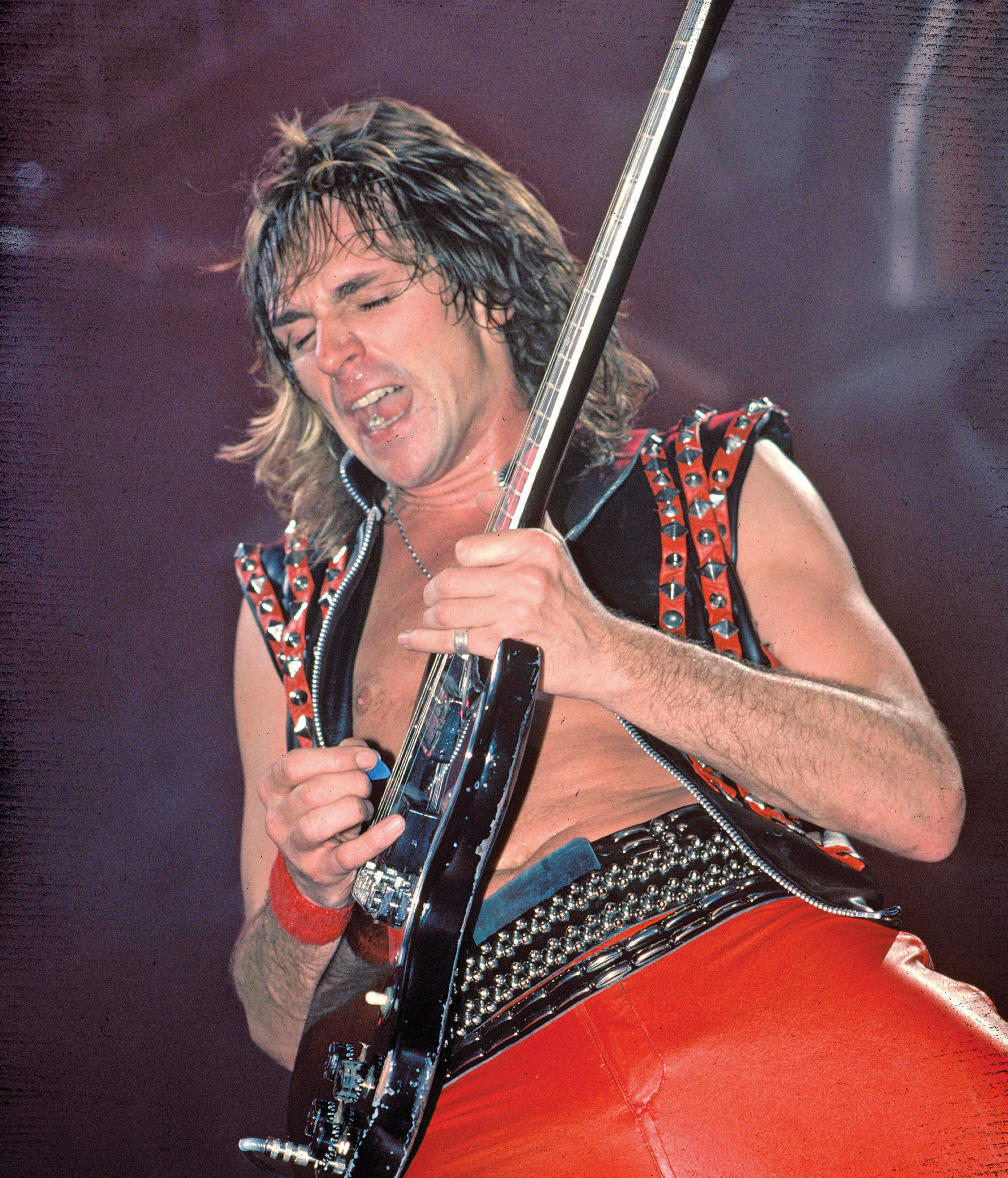

Judas Priest Legend Glenn Tipton Speaks Candidly About His Struggle with Parkinson's Disease

The last 15 years have been filled with ups and downs for Judas Priest, and especially guitarist Glenn Tipton. Following Angel of Retribution, the band’s 2005 comeback with Rob Halford—his first with Priest since 1990’s Painkiller—the band crafted the poorly received 2008 concept double-CD Nostradamus.

After a lengthy tour, they strived to redeem themselves with 2014’s Redeemer of Souls, but they had to write without longtime guitarist K.K. Downing, who quit in 2011 and was replaced by the nimble-fingered Richie Faulkner. From the start, it was clear that Richie was musically gifted, but no one knew how he would perform in the studio.

As preoccupied as any band member would have been under the circumstances, Tipton was confronting an even more daunting issue. The metal veteran was experiencing problems with coordination that impaired the speed and accuracy of his playing. He visited a neurologist, who confirmed Tipton’s worst fears. The guitarist had Parkinson’s disease.

“It was upsetting, but I wasn’t really shocked because I sort of thought it was Parkinson’s. I probably hoped it wasn’t but the doctor said it was,” the soft-spoken Rock and Roll Hall of Fame nominee tells Guitar World in his first interview since revealing his condition in mid February.

Not only was Tipton diagnosed with Parkinson’s, he was told by the doctor that he had likely already had the disease for between 10 and 15 years. Rather than greeting the news with despair, he tried to be optimistic. “Hearing that I already had Parkinson’s for a long time made me even more determined to fight,” he says. “I could still play, so I just continued recording and touring.”

Stocked with prescription medication, Tipton worked with Faulkner to write and record the solid, if predictable, Redeemer of Souls and toured for the album. Then, after some time off, Faulkner and Halford met Tipton at his home studio in the Midlands in England to work on Firepower. The guitarist’s condition had gotten worse.

“I was with Glenn for all of his guitar work, and he worked really, really hard,” Halford told Fox Radio. “Imagine, this guy in the 10th year of Parkinson’s. I’ve never seen anybody so brave in the fact that every song was a challenge for him to make it work, but he did—consistently, day after day.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

When they were done, Judas Priest had recorded their strongest, most consistent album since Angel of Retribution and Tipton had laid down some of his most fluid and versatile guitar lines in years. He planned to join Priest on the Firepower tour and even began rehearsing with the band. Then, about a month before the opening date, Tipton realized he could not guarantee that he would be able to execute an energetic, precision performance with the band night after night.

“I decided that it was really going to be too much for me,” he told Guitar World over the phone from his home in the Midlands, 10 days before the release of Firepower. “With the medication and the time zone changes and everything else, I realized it was time to retire—from touring at least. I don’t ever want to compromise Judas Priest. It’s too big a part of my life.”

Two weeks before Judas Priest flew to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, for the first date of the Firepower tour, Tipton opened up about his long struggle with Parkinson’s and exactly what triggered his decision to stop touring. He also discussed why no one outside the band’s inner circle knew about his health problem and what role he might play in Priest during the Firepower tour and beyond.

It’s pretty amazing that you were able to write and record some pretty complex guitar parts for Firepower considering you’ve been struggling with Parkinson’s.

Yeah, obviously it’s something that has gotten worse as the years went on. I wasn’t exactly struggling with things that I could play in my sleep, but I knew that there were restrictions governing my speed. The fluency and coordination weren’t there. On an album, of course, you can always redo something if you don’t play it right, so there was never a problem there. But you don’t have that option onstage.

You originally planned to tour for Firepower but backed out just 33 days from the first scheduled date.

I wanted to do it. The band have been very supportive and my ability as a guitar player got me through. Even up to the rehearsal stage, I was capable of playing 99 percent of everything, but you can have good days and bad days with Parkinson’s, and I didn’t want to go onstage with that possibility looming. I wanted to go onstage with total confidence if I was going to do it.

Have the medications you’ve been taking slowed down the progression of your ailment?

You can never tell, really, because you have to take such a cocktail of medications. And when you’re out on the road, just being in that environment can affect you and you can have a bit of trouble there that affects your playing. So I don’t know if you can put it down to 80 percent Parkinson’s and 10 percent travel and whatever percent medication.

In a press release, you mentioned you were still a member of the band and would continue to write and record.

I haven’t at the moment decided to leave the band, but I shan’t be touring 18 months at a time anymore. I’ve always felt strongly about my music and every aspect of Priest. You’ve got performance and you’ve got recording and you’ve got songwriting. Creativity-wise, the Parkinson’s has never affected my songwriting or my ability to play and produce songs as part of the writing team.

Would you like to work on another studio album with Judas Priest when they return from the Firepower tour?

I’ll see how the band feels when they finish the tour. With regards to writing, I sincerely hope I maintain a contribution to the band in terms of songs and composition.

Was there a song in particular or a solo that kept tripping you up and made you realize you could no longer perform at your peak ability onstage?

No, it wasn’t any one particular song. It’s just that my life’s gotten to the point where I’ve got to put my health before the band. I’ve always put the band before my health, as would any other member of Judas Priest. It was a difficult thing to do, but I decided enough’s enough. I’ve got to make a decision one way or another.

Did you have hand tremors, muscle stiffness or balance issues—all of which are symptoms of Parkinson’s?

I don’t suffer too much from tremors. It’s more coordination and getting up to speed. It’s almost like you’ve got a governor sitting at the speed you can go to and you can’t go through the barrier. And if you’ve seen Priest onstage, with the adrenaline rushes, you can see why that might be a problem.

When you were first diagnosed, did you figure that this was going to change your life dramatically or were you determined to fight?

I had a desire to overcome it and always will. Every now and again, I had to revise the way I play guitar and rethink and revamp things. I’d play in a slightly different way to compensate for the drawbacks.

Did you change the way you fingered or fretted the notes?

Yeah, I had to reinvent how I played the guitar in various ways. And that was part of the challenge for me that I enjoyed. I liked taking the challenge and overcoming it.

What is more impaired, your left or right hand?

My left hand. Sometimes the coordination just isn’t there the way it had been.

In a press release, the band said you might be joining them onstage at some shows.

The band have asked me if I’ll get up and do some of the shows and do some encores with them. And that’s fine. There’s part of me that knows I could get through a set. But to do an 18-month world tour is being optimistic.

Are there any particular cities where you’d like to take the stage?

No, I’m not sure yet. I have to go over and see the lads and we’ll talk it through. There’s a strong possibility I’ll do a few shows. But at the moment, I’m still coming to terms with the fact that, as far as world tours go, that’s the end of the road for me.

Do you think retiring from touring is a way for you to go out on top?

Well, I don’t want to compromise the band in any way and I’d like people to remember me as a notable guitar player, not someone who is struggling to get through the set.

You’ve done so much recording and touring during the 10 to 15 years that you’ve been afflicted with Parkinson’s disease, and you’ve always risen to the occasion. That’s not only admirable, it creates hope for fans who may be struggling with Parkinson’s or have friends or family with the condition. In that respect, you’re a different kind of a role model than most veteran guitarists.

That’s one of the things that I hope will come out of this. I have inspired a lot of people musically, and I hope I can inspire some of them physically and mentally. If anyone out there has got any problems, hopefully I can inspire them to adopt a very positive attitude and overcome it.

You could very easily have said you didn’t want to tour so you could be at home with your family. You never had to reveal that you were suffering from Parkinson’s disease. Why did you decide to tell fans that you have this condition?

Because it’s the truth. There’s no need to fabricate and try to avoid the issue. I don’t like to lie about things, so I thought it was the right thing to do. And I’ve gotten some wonderful messages in the last couple of weeks and that makes me feel a lot better.

Conversely, why didn’t you tell fans about your situation years ago and show them you could still perform as well as anyone?

I didn’t want to walk onstage with a sympathy vote. I wanted to walk onstage and do my job as a guitar player with Judas Priest. I didn’t want people to say, “Oh, Glenn’s got Parkinson’s. It’s a shame for him.” I didn’t want anyone to feel sorry for me. It’s not me. So, I’ve just worked hard at overcoming and adopted a very positive attitude. And for a long time, that’s worked for me.

What’s been the greatest challenge of having Parkinson’s beyond the playing obstacles?

I’ve had some pretty down days. Parkinson’s can do that to you. Obviously, you’re not on top of the world. Some of the depression comes from thinking, God, I’ve been a part of Priest for 50 years or so and I’ve got to let go. It’s very difficult but I’ve tried to be strong and positive. I always try to make a joke of it: “It’s very difficult when you’re on the road to eat peas and Chinese food [with chopsticks].” But really, I’ve got no regrets. Now was the time to let go.

Andy Sneap, who played professionally in the bands Sabbat and Hell, seems like a good choice for a fill-in. And whatever happens after the tour, Richie Faulkner seems ready to carry the torch as the band’s main lead guitar player.

Richie’s a phenomenal guitar player. He’s brought so much strength to the band. And he’s helped me so much get through some hard times. He’s a great guy and fits right into Judas Priest so well. If anybody could carry the torch, it would be Richie.

You’re 70 years old, which is older than a lot of metal musicians who have left the business.

I’ve had such a great a great run. I’ve enjoyed myself so much with Priest. It’s been a major part of my life. I’ve said it before in interviews when people would ask, “You know, you’re getting on a bit in age. How long will you keep doing this?”

Would you be interested in producing other bands or working in the music industry in some capacity?

I’ll see what happens. It’s early days yet. Up until a month ago, I was going out on tour. So I’ve got to put some thought into the future and my family and my loved ones. At some point there’s gotta be an end to it.

Jon is an author, journalist, and podcaster who recently wrote and hosted the first 12-episode season of the acclaimed Backstaged: The Devil in Metal, an exclusive from Diversion Podcasts/iHeart. He is also the primary author of the popular Louder Than Hell: The Definitive Oral History of Metal and the sole author of Raising Hell: Backstage Tales From the Lives of Metal Legends. In addition, he co-wrote I'm the Man: The Story of That Guy From Anthrax (with Scott Ian), Ministry: The Lost Gospels According to Al Jourgensen (with Al Jourgensen), and My Riot: Agnostic Front, Grit, Guts & Glory (with Roger Miret). Wiederhorn has worked on staff as an associate editor for Rolling Stone, Executive Editor of Guitar Magazine, and senior writer for MTV News. His work has also appeared in Spin, Entertainment Weekly, Yahoo.com, Revolver, Inked, Loudwire.com and other publications and websites.

![[L-R] Joe Satriani wears dark shades and smiles as he solos on his Ibanez JS signature model; Ian Anderson strikes a pose as he plays the flute; Yngwie Malmsteen pulls his aviators down to give the camera some eye-contact in this portrait from 2019](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/qpBDNvdaGjWXpBHjWdQG7S.jpg)