Jack White Breaks Down His Ambitious New Album, 'Boarding House Reach'

Given Jack White’s well-documented obsession with the number three, it was a sure bet that his third solo album would be a genre-busting magnum opus. Boarding House Reach is all of that and then some—a cataclysmic mash-up that sets the disruptive cadences of EDM, hip-hop and musique concrete against White’s heart-on-sleeve, homespun core of blues, country, gospel, folk and, yes, rock and roll. As always, White’s woolly-mammoth guitar riffs and plaintive, edgy vocals anchor the proceedings. But Boarding House Reach is nonetheless a challenging disc. Then again, when has White been anything but challenging?

“This is probably the album that sounds most like how I was actually imagining these songs in my head,” says White. “I’ve attempted to do that on records in the past, but you get as close as you can and then say, ‘Well, that’s about as good as it’s gonna get. Time to move on.’ But this was more of a scenario of, ‘No, that’s not the right tone, or the right reverb. Let’s keep pushing till we get there.’ So I knew that was going to make the record a lot stranger. ’Cause I know my brain isn’t as simplistic as the songs I’ve put out in the past in my life.”

Now there’s an understatement. The disconnect between the simple lineaments of garage rock and the byzantine labyrinth of White’s hyperactive imagination is what fueled the White Stripes’ early 2000s emergence as the great red-and-white hope for the future of rock and roll. It was like an ocean of emotion and an avalanche of ideas all straining to pass through the eye of a needle—in this case the primordial garage rock triumvirate of guitar, drums and vocal. The power of that creative tension propelled a pair of misfits named Jack and Meg White onto the mainstream charts with hits like “Seven Nation Army,” “Fell in Love with a Girl” and “Icky Thump.”

“‘Seven Nation Army’—that was me trying to write a song without a chorus and still get people’s attention,” White confides. “At the time, I thought it was just a little experiment that not many people would care about. It was just a challenge to myself: ‘I’m not gonna have a chorus in this song. See if I can get away with it.’ And on that one, we really did get away with it! Other times, it’s harder.”

If White challenges his listeners, he challenges himself even more ardently.

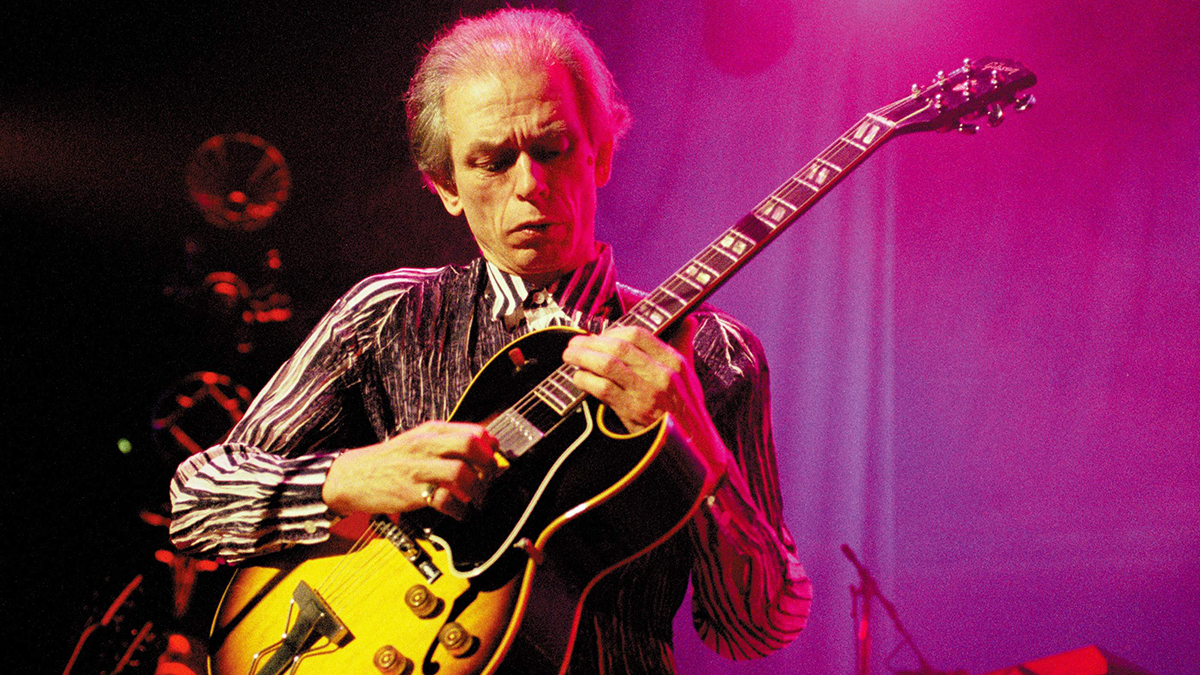

From his earliest days in Detroit’s underground rock scene, he seems to have understood that something beautiful, if brutal, comes out of an artist’s struggle with self-imposed limitations. That’s why he opted for thrift shop guitars like the Montgomery Ward Airline and mid-century Kay archtops. It can be difficult to play or coax a decent tone from yesteryear’s budget-line guitars. But with these humble tools, White forged a fuzzedout, Whammied-down new rock guitar aesthetic for the 21st century.

Over the years, White has continued to grow by placing himself in new contexts, sometimes outside his comfort zone. From the Raconteurs to the Dead Weather, this approach has produced consistently stellar results. And White is perhaps the only person in musical history who could produce standout recordings with everyone from Loretta Lynn to Beyoncé. His solo albums, starting with 2012’s Blunderbuss and continuing with Lazaretto in 2014, have been a platform for some of his most daring sonic exploration.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

But Boarding House Reach takes things to a whole new level. In sessions that took place in New York and L.A., White surrounded himself with players who’d performed on his previous solo discs, including drummers Carla Azar and Daru Jones, bassist Dominic Davis and violinist Fats Kaplin—instrumentalists White describes “master musicians that I knew, who were country, rock and roll, folk and bluegrass-based people.” But to this familiar mix he added a slew of newcomers, including bassist Charlotte Kemp Muhl from the Ghost of a Saber Tooth Tiger, bassist NeonPhoenix who has worked with Kanye West, Lil Wayne and Jay-Z, drummer Louis Cato who has backed Beyoncé, Q-Tip, John Legend and Mariah Carey, percussionist Bobby Allende and synth players DJ Harrison and Anthony “Brew” Brewster.

“I really wanted to be in a room full of people I’ve never played with before,” he explains, “who are totally from farther away, musically. I wanted to get deeper into using EDM musicians and experimental noise band musicians. Perhaps down the road I’ll get more into that. But at this moment, the type of musician I was looking for was hip-hop musicians who could play onstage live behind someone like Jay-Z. I think that calls for a particular type of musician, who can groove and understand that kind of drum beat and those kind of samples, and bring them alive.”

White’s squalling, rambunctious, post-Zeppelin, post-modern blues guitar work shines through the complex mixes. The grainy, gargantuan riffs that power tracks like “Why Walk a Dog?” and “Over and Over and Over,” not to mention the wildcat soloing on “Respect Commander,” could only come from the heart, soul and fingers of Jack White—even though he did it all on an Eddie Van Halen Wolfgang signature model guitar throughout.

And however far afield the sessions ventured, they were all grounded in a set of simple four-track demos that White created in a small apartment he’d rented in his adopted hometown of Nashville—away from the distractions he has as a family man and head of the multifaceted Third Man Records label.

“It was a great way to go someplace else in town, lock the door, and I was there by myself with no phone,” he says. “There was no way anyone could get hold of me. I was there only to work on music. There was no other choice. There was nothing else to do. That’s a really great feeling—to force yourself into something that’s almost a prison cell. ’Cause I’ve often fantasized about that. ‘Oh, going to prison, man. It would be nice if they let you have a guitar. But, God, what if they didn’t let you have a guitar? Oh man, that would be really difficult.’ ”

Fantasizing about going to prison? Welcome to the mind of Jack White. Speaking from Third Man HQ in Nashville, White let Guitar World in on the tortuous processes behind the making of Boarding House Reach.

What was your working method like in the tiny apartment where you laid the foundation for Boarding House Reach?

I basically tried to write melodies and lyrics without instruments. On one track, I was playing kick and snare on a drum machine with my left hand while I was singing directly onto the second track. I had to do it all very quietly so I wouldn’t bother the neighbors. So I had a vocal with a timed click and a drum machine. I could add other instruments later. And it was great, because I didn’t even know what key I was singing in. I didn’t know what the chord changes would be like. I figured I would make them into songs backward. In other words, I usually write on piano or guitar. I write some music and then try singing along with it to turn it into a song. So it was backward for me to start with the vocals first.

There aren’t a lot of chord changes on some of the tracks. They just groove along on the tonic, basically.

Every song on the album goes somewhere different. So, yeah, some of them are very groovy. I like that, because I spent a lot of time on past records really filling up every second with a verse or a chorus, so that there’s never more than three or four seconds without any vocals happening. And that doesn’t give the band much time to breathe. So I wanted to do more of that with these songs. Let people get into a groove. In the past, I was usually trying to get songs down to under three-and-a-half minutes. This time I wasn’t so concerned with that—although I had a condensing job with some of these songs anyway. Some were 30-minute jams that had to be taken down to some kind of length where I could fit a lot of songs on the album. Because I didn’t want to do a double album.

So did anything from the apartment demos make in onto the final recording?

A few things. There are keyboards on “Connected by Love” that are from that room, and the entire recording of “Ezmerelda Steals the Show” was done completely by me in that room. It’s kind of nice to have one song that was created in that room make it all the way to the pressing plant unchanged. To be able to do every step of the process, all the way to owning the pressing plant—that’s real DIY! I was very proud of that.

For you, how does the guitar fit into this new, expanded, somewhat electronic soundscape that you’ve forged on this record? Did you find yourself modifying your approach to the guitar?

Very much so. Because there was so much complicated stuff going on with this record, I really wanted to find, ‘What’s the easiest guitar out there to play?’ I’ve been playing the most difficult guitars to play all my life. But with all the changes I had to deal with—people I never played with before, two days of sessions in New York, two in L.A.—I didn’t have time to monkey around with antique guitars in that moment.

I was looking around, and I saw this interview with Eddie Van Halen about this Wolfgang guitar of his. He said, “I wanted a guitar that didn’t fight me, at all.” I said, “That’s the magic word.” I immediately went out and got one of those to try. And, oh my God, I just couldn’t believe how easy it was to play. People don’t know what it’s like to play a piece of plastic onstage and have to keep it in tune with a whole band around you. I knew it was hard, what I’d been doing. But I didn’t know how hard until I played something like that Wolfgang guitar. You can go crazy and bend the tremolo arm all the way down and it completely stays in tune. That’s absolutely insane. It was what I needed at this point in time to push myself as a guitar player into a new zone, and also just to displace some of the pressure.

And that’s put you on a kind of signature model binge?

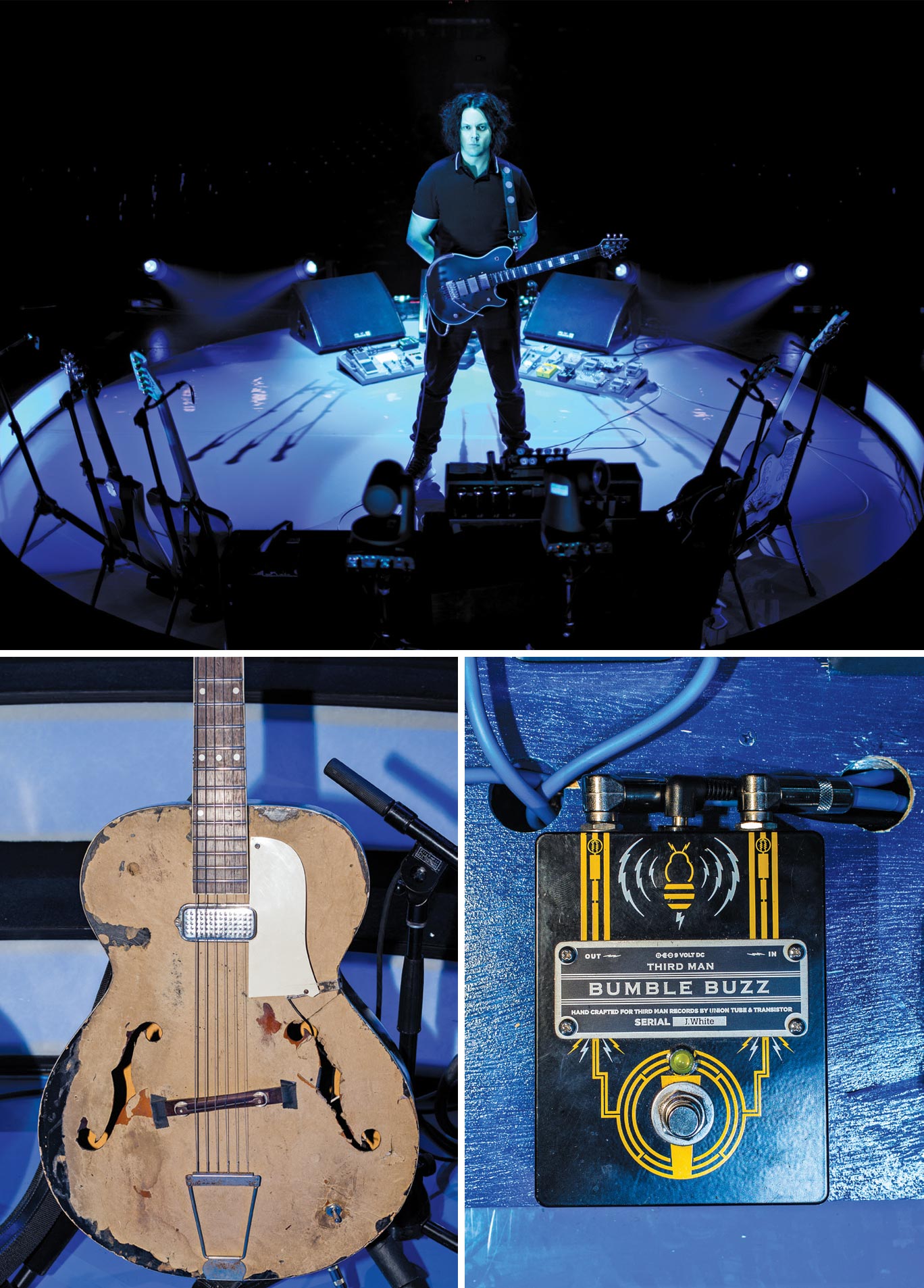

I thought, On this tour, I want to take three guitars that were designed by other guitar players and add my own twists to them—my own accoutrements that make sense for what I’m trying to achieve. One was Eddie Van Halen’s Wolfgang. The next one was St. Vincent’s signature model for Ernie Ball, which is designed for women, which I think is amazing. So I thought it would be kind of interesting for me to play that. And then there’s this guitar Jeff “Skunk” Baxter designed for Gibson—a Firebird. It has three mini humbuckers that can be switched to single-coil. I liked that because I had done that on the guitars I had designed—these Triple Jet Gretsches I’ve been using for years.

So I asked Gibson if they would make me that Firebird in the style of their Fort Knox Les Paul. They had given me a Fort Knox Les Paul for a Grammy event I did with them. They asked me to pick out a guitar and I thought of the Fort Knox. I don’t really like gold, but this is so over-the-top gold I figured I’d love it. So I said, “Thank you very much, I’ll take that one.” They sent over a Fort Knox Les Paul and a Fort Knox Flying V they made for me as an extra present. Which was really nice. But I revolve everything around the number three. So now I had a conundrum. I needed a third Fort Knox guitar. I told them. “I’ll pay for it, but would you be able to make me this Skunk Baxter guitar in the Fort Knox style, with a maple neck?” It’s the heaviest guitar that I’ve ever lifted, and the sustain is outstanding. You could murder a badger with it.

So what’s the common denominator that links Van Halen, St. Vincent and Jeff “Skunk” Baxter?

I feel like each of these players really had a lot to do with the design of their guitars. They didn’t just put their names on something that someone else had designed. Also, these were guitars I could take and add my own twists to.

Are all three players that you admire?

I really do admire all of them. I don’t know that much about Skunk Baxter, beyond his work with Steely Dan and the Doobie Brothers. I don’t know as much about him as I do about St. Vincent and Eddie Van Halen. I think St. Vincent is one of the best guitar players out there today. I think she doesn’t get enough credit for how incredible her guitar playing is. It’s very angular and very inventive. And Eddie Van Halen, of course. It’s absolutely insane the things that he invented that we take for granted today. And I know he’s always been a guy like me, who likes to work in the garage and mess with things. So I know his style of design was coming from the garage. That inspired me.

The idea of gendered guitar design is interesting. Given that St. Vincent designed the guitar for women to play, does it feel comfortable for you to play?

It’s kind of tiny on me. I definitely look gigantic holding it. You’d have to ask her what her design specifics were—hand size or whatever. It’s a very unique body style. It’s hard to come up with a new body shape, man. Everyone’s tried over the decades. You can see the trail of the dead. But the St. Vincent guitar looks great and sounds great. She gave me that guitar. She sent it to me as a present. That was really kind of her. I put these blue aluminum Lace sensor pickups on it, and an interrupter switch so I can turn the whole guitar on and off and get the kind of effects that I try to accomplish. And I put a black neck on it.

Are all three guitars heard on Boarding House Reach?

No. The record is only the Wolfgang. That’s all I had on the record—just that one guitar.

You also tried the Van Halen 5150 amp, but that didn’t work out?

It’s a great sounding amp, but it wasn’t really what I’m used to. My magic thing, for what I do, is 15-inch speakers and the combination of Fender and Silvertone amps mixed together. Over many years of working with Fenders and Silvertones, the key was really finding that 15-inch speaker. Somewhere around Icky Thump I started using that. And if you look through history, you’ll find a lot of guitar players like Duane Eddy and Stevie Ray Vaughan using 15-inch. In the early days of the White Stripes, I had an 18-inch speaker with a gigantic magnet on it. I put it into a Silvertone myself, and it was the wrong ohmage and shit. But it broke up in a really great way.

So my thing now is really the Fender Vibroverb 15 with the 100-watt Silvertone. When I was younger, it was hard to find a 100-watt Silvertone. Now you can find them on Reverb and eBay in two seconds. Back in the Nineties, I had the 50-watt Silvertone and I was looking everywhere for the 100-watt. I thought maybe it was a myth—didn’t really exist. But when I finally found one, it changed the whole thing for me. There’s six 10-inch speakers in that, so I really did need the large, 15-inch speaker to go with it. So when I put that Silvertone and the Vibroverb 15 together, everybody in the band was like “Holy shit!” They could immediately hear that it was great. When everyone in the band says something like that, you know it’s not just you obsessing over tiny details that no one else will notice.

So what’s behind that super-low sound for the guitar solo in “Why Walk a Dog?”

[Laughs] Everybody asks that! The best one was when I came back in the control room after I played it and the engineer said, “What the hell was that?” This is a pedal made by Mantic, and it’s called the Flex. My company, Third Man, is going to be releasing a version of this pedal in collaboration with Mantic. It’s just an amazing thing. And for the main riff on another song from the album, “Over and Over and Over,” I used a pedal from another company that Third Man distributes, Union Pedals in Vancouver, called the Bumble Buzz. I had tried recording that song many times for the past 13 years, and for some reason it never worked out. And when I tried this Bumble Buzz pedal, I thought it wasn’t gonna work either. But that was the tone I was waiting for this whole time.

The lyrics in “Over and Over and Over” reference the Greek myth of Sisyphus, who was condemned to roll a boulder up a hill for all eternity, only to have it roll back down the hill each time. So is the song some kind of statement of existential angst on your part?

Well, I’d recorded the song so many times. And I never wrote lyrics for it, because I thought the song was never gonna happen. But when it finally came together for this record, I thought, Oh shit, now I gotta write vocals for this. And yeah, the first thing that popped up in my head was Sisyphus, pushing that rock up the hill and having it roll down and pushing it back up again—over and over and over. So it’s funny that it’s called “Over and Over and Over.”

Another thing about Boarding House Reach is that you’re exploring spoken word, as opposed to singing, more than you have on any past record.

Definitely. I’ve said in the past that all the things we do with melody, singing, guitars, drums and rhythms…all these things are just to get a story across. But if you rewind that all the way down to just the words, it’s a real challenge whether you can keep people’s attention with that. So I was challenging myself with that a bunch. And also playing with the idea of what they’ve done with hip-hop music—how the words get spoken, or spoken in a cadence, or in a semi-melody. And that goes all the way back to folk tradition. Bob Dylan’s songs in the Sixties like “Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues.” And going back to the talking songs of Woody Guthrie, like “Talking Dust Bowl Blues.” Hank Williams did a lot of talking in his songs, too. There’s a lot of different ways you can do that. Sometimes it’s called rap, sometimes it’s called poetry. Sometimes it’s street poetry, sometimes it’s called spoken word.

There are also more classically structured melodic, verse/chorus songs on the album. “What’s Done Is Done,” for instance, is kind of a country song with some gospel overtones.

Yeah. That was written in that apartment too. I just wrote the vocals first by themselves. Then I added things to it and it became countryish. The singer on there, Esther Rose, said, “This almost sounds like a classic Patsy Cline kind of a song.” It really does, and that immediately made me want to use a lot of modern equipment on it. So we used drum machines and synthesizers instead of acoustic instruments—a really big juxtaposition there. You almost don’t notice it for a second. And then when the solo kicks in, all the acoustic instruments kick in—acoustic drums, electric guitar… standard stuff. Then it goes right back to synthesizers and drum machines again. So it’s sort of interesting. I almost wanna play that song at the Grand Ole Opry with just a drum machine and synthesizer and the girl singing. It would be interesting to see if they would be able to handle it! [laughs]

Speaking of interesting experiments, how did you create that loop that runs through “Hyper-misophoniac”?

Not to sound like I’m plugging products here, but there’s this company Critter and Guitari that made a synthesizer called a Septavox during the time I was working on the record. Third Man is co-distributing that as well. And that’s what I used on that track. Only I don’t know where the beep in there comes from. I think maybe the battery was dying as I had this loop happening. So I recorded it and asked the band if they could play along with it. And the band was just, like, “Uh, how are we supposed to play along with this?” That got me excited. I actually rubbed my hands together and said, “Ooohh, this is going to be good.”

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.