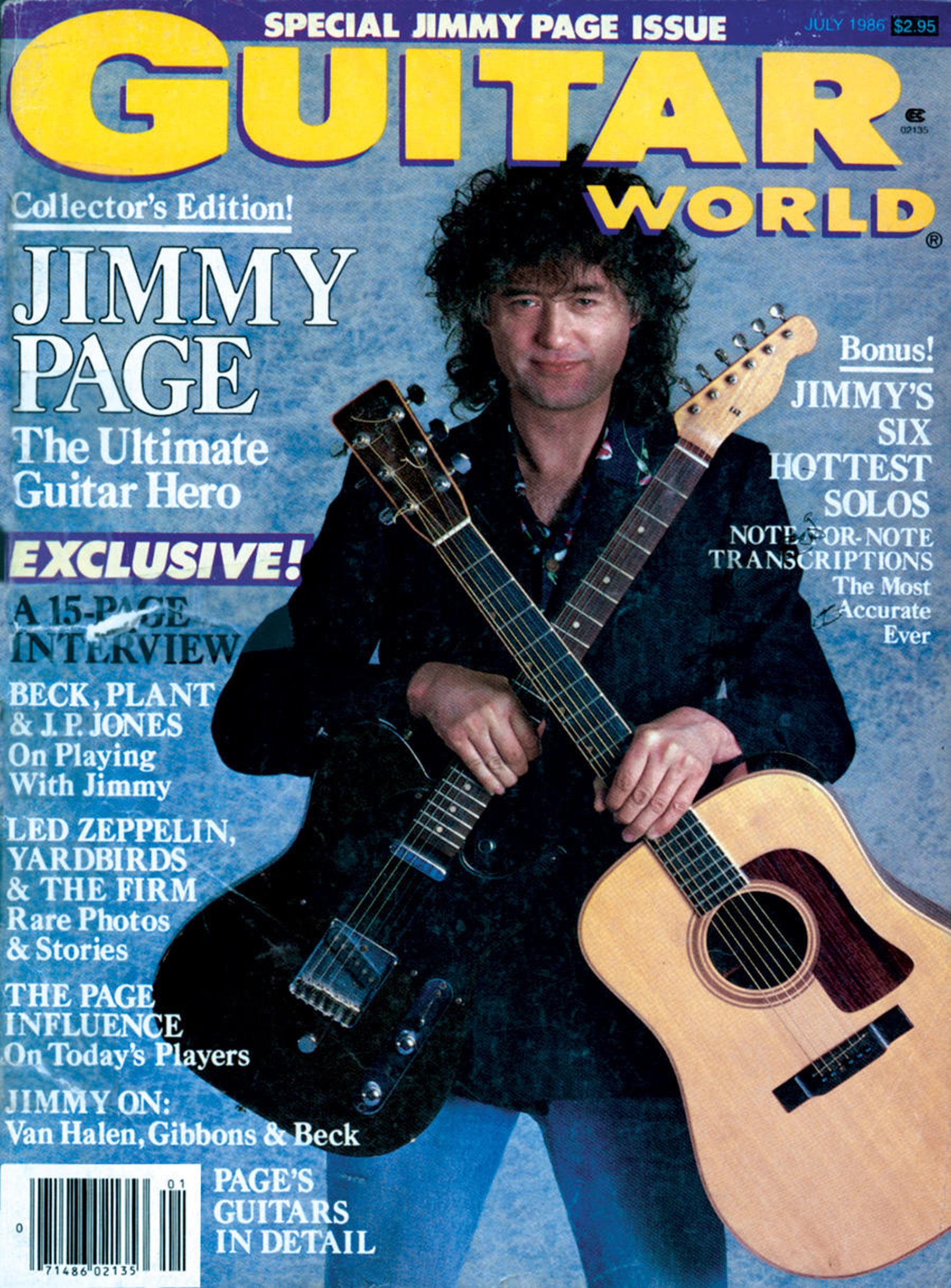

Jimmy Page in the Eighties: The Firm Guitarist Talks Teles, ARMS Concerts, Live Aid and Eddie Van Halen in 1986 Interview

The following classic interview is from the July 1986 issue of Guitar World, better known among longtime GW fans as "the Jimmy Page Issue."

The weekend had all the earmarks of a lost one. Sleepless nights spent wondering if the next day would produce the promised sitting with guitarist and composer Jimmy Page. There were words of illusory wisdom containing hope but having little to do with reality: “It looks like it’s going to happen tomorrow,” as espoused by Firm manager Phil Carson. But after a delay of two days (a mere trifle really when one considers I waited five days to see him when I interviewed Page in 1977), the meeting took place.

Jimmy looked tired but spry. He smiled, exchanged greetings and looked at a photo he and I had taken during our first encounter nearly 10 years ago. Remembering that tête-à-tête, his body seemed to relax. Phil Carson had explained Page’s usual aversion to interviews as a reaction to past “hatchet jobs.”

As I sat down to talk with Jimmy, I realized that I must have passed some kind of security check. Jimmy’s personal guitar technician, Tim Marten, was always close by. His presence was welcome and a stabilizing influence.

Page eyed the list of questions and after I explained that our talk would revolve around more of an overview of his work with the Firm and Led Zeppelin than an in-depth probe into playing techniques, guitars and such (this would be handled by Marten), he took a swallow of his gin and tonic and we were on our way. I took a long swallow myself—of oxygen—let out a deep breath and tried to calm the thundering of my heart. I couldn’t.

After going out on so many tours and putting together so many stage productions, what is it about it the business that still excites you? Where does the energy come from?

Well, just generally being able to play the guitar. But really it’s for the people who have followed, for instance, Zeppelin. Actually I’ve been quite overwhelmed with the way people have showed me their warmth. It’s fantastic.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

It must feel good.

It bloody well does, sure it does. In fact, it’s just great to be playing again and to be with a band as well.

How different is this second Firm tour from the second Led Zeppelin tour? What has changed?

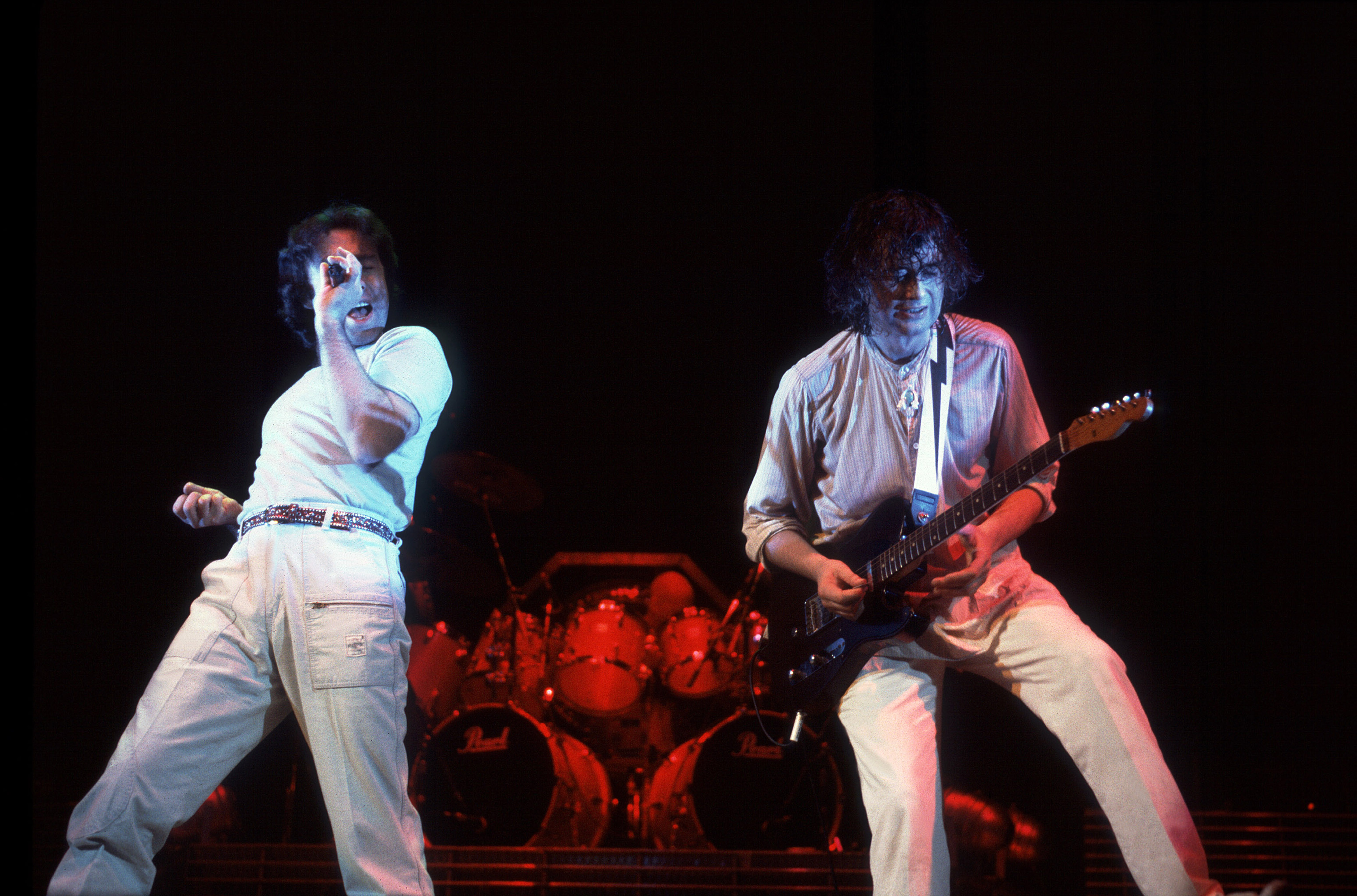

About 20 years! Well, what would you think has changed? I think everything would be bigger and more difficult to put together. And more pressure, possibly. Well, obviously, yeah. Yes, it is a bit like that, of course...if one thinks of it like that. When the Firm first got together, Paul and I both wanted to play in front of an audience. It’s quite difficult in a way to be able to do something in the correct perspective to be truthful. It’s like Robert [Plant] and Jonesy [John Paul Jones] and I wanted to have a play together and suddenly you’re touring before you’ve even got any choice. Do you know what I mean? So when you say bigger, bigger, bigger—yeah. And certainly this is not supposed to be bigger than anything. In fact, it’s supposed to be quite scaled down.

What new direction has Paul Rodgers brought to your music? Was he good for you?

Well, he was certainly good for me and I’ve been good for him, too. Purely because the way that we got together, publicly anyway, was the ARMS Tour. Because of the ARMS Tour and the fact he volunteered to come forth, so to speak, I respected that.

Is it a different approach working with Paul than it was working with Plant?

Well of course it is. After you’ve been with someone, Zeppelin and Robert, for that amount of years—I don’t know how many years it was now—you get to know each other in a band very, very well. It can almost be an ESP type of thing. With Paul, his phrasing is totally different [from Robert’s]. I would think that Robert was like a vocal gymnast. And Paul, I’ve never heard him sing a wrong note; he’s such a technical singer. He really is. And yet he has a quality within his voice that on the ballads he does is really caressing. And yet it’s really vibrant in a way.

Were you a fan of Free?

Yes, I did like Free.

Did you ever play any shows with them in the early days?

No, no we didn’t. We never did. Zeppelin were doing their first gigs right around the time Free were doing theirs. No, but we never actually crossed paths. It wasn’t until SwanSong and Bad Company.

Does Paul’s playing a second guitar bring something new to the music?

Well, it’s good to have another instrument there, yeah. The keyboards are good. The thing is, he can do that so it’s good.

One would imagine that playing over keyboard parts and voicings might open up your playing in different ways.

It depends on what the number is, really. I see what you’re saying but usually if Paul is playing an instrument, you can bet your life it’s one of the songs he wrote because he’s written it on that instrument. If it’s his song and he’s written it himself, obviously the best thing I can do is try to complement it with the guitar. And if I weren’t like that, I guess I wouldn’t be in the band.

You started this conversation by saying how overwhelmed you were to the response you were receiving on this tour. How does it make you feel that a magazine such as Guitar World is dedicating an entire issue to you?

How does make me feel? I’m honored that that’s the case.

What I mean is, there is so little that you haven’t done in terms of guitar exploration...

There’s so much that can be done on the guitar. I’ve only done a few bits and pieces, really, considering what can be done. Alright, let’s go from one extreme to the other. The gut-strung guitar, the classical guitar, that is a whole different world on its own. And we’re talking to guitar players here so they know that. It’s really fine within its horizons. And then you get into the steel-strung acoustic guitar and the electric guitars as such. When you think what the guitar can do and what every individual player does with a guitar, everyone has their own identity coming through the guitar. And then to talk about exploration and what I’ve done, there’s so much that can be done on the guitar. And that’s what is so good about the guitar—everyone can really enjoy themselves on it and have a good time, which is what it’s all about. Right?

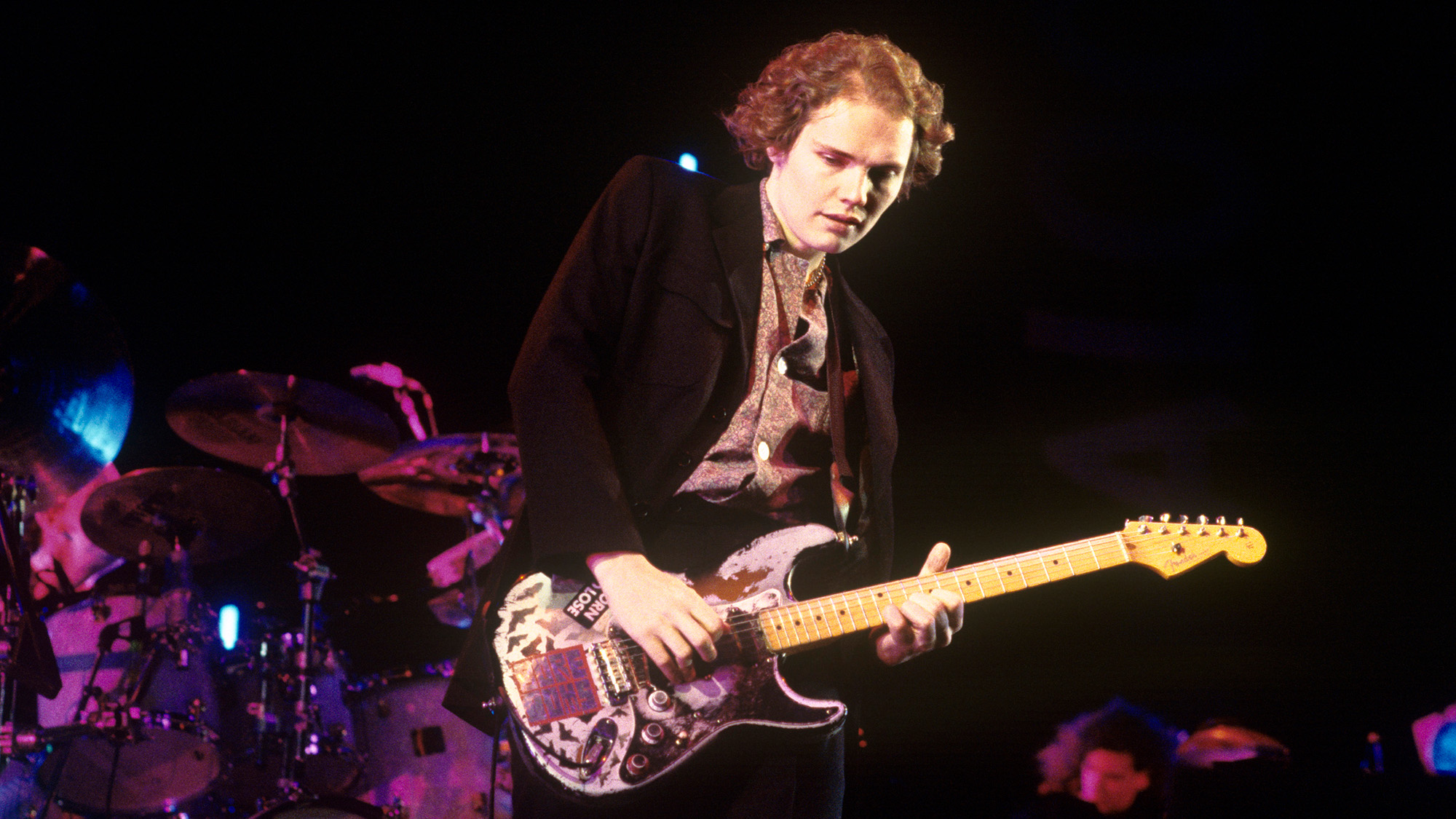

Lately, you’ve been playing the Telecaster far more than the Les Paul. With Zeppelin you rarely used the Fender and yet with the Firm that’s just about all you use. Do you think your style has changed?

Of course it’s changed. I mean you’ve changed from 15 years ago and who hasn’t? But the Telecaster has the StringBender mechanism what took me about two years to come to terms with [laughs]. No, not really, but I’d say it took a year, honestly. Considering it’s only moving [changing the pitch] two frets or whatever, you can see how slow it is for me to get things together [more laughter]. To be truthful, it was difficult to work through it—up the neck, so to speak. But it came to the point that as it was such a good thing to cheat with... [hearty laughter] Alright, go on.

Initially, where did the idea come from to even try a StringBender? Was it a feeling of “Well, let’s just try this?”

Oh, no. I tried to play pedal steel guitar years back and that was a totally different situation within itself. I did like the idea of the pedal changing the intonation of the string. I heard Clarence White as a guitarist on the Untitled LP by the Byrds and all the stuff he was doing I thought was quite amazing. And there were parts that I couldn’t physically do as far as trying to do it on the guitar. And I heard that there was this mechanism within the guitar which was the Gene Parsons/Clarence White StringBender. And I was lucky enough at one point in time to see the Byrds play, though I saw them many times, at a hall in Dallas. And at the end of a very, very pleasant evening hearing them playing and talking to the members of the band, Gene Parsons made up one of these StringBenders for me.

[At this point there is discussion between Page and guitar tech Tim Marten about the StringBender patent and Parsons’ involvement with Fender.]

I suppose it’s just like a tremolo arm for all the guys that play a Strat. Of course, it is. It’s a gadget but you work with it accordingly. I must admit it took me a year to get used to but it wouldn’t take me a year to get used to a tremolo arm.

The StringBender has become such a big part of the Firm’s sound.

I’m just bending the second string [laughs].

An identifiable part.

Maybe so, maybe so. It’s a certain thing you can do within that mechanism that you can’t do with an ordinary guitar. I guess that’s it.

And you haven’t played much Stratocaster in recent years, really.

No, not really. I’ve used it every now and again. Usually for the tremolo arm—that whole chord sink down and rise up sort of thing. That’s what I use the tremolo arm for. Anyway, that’s the only time I ever got to use it because I always used the Les Pauls. In the early days I used a Telecaster. But once I got into the Les Paul, that was that really because it’s such a fine instrument to play. And it also doesn’t have a tremolo arm. Yeah, it was much later on that I started using the Stratocaster.

Do you listen to someone like Edward Van Halen and the way in which he uses a tremolo arm?

I am extremely aware of him, actually, and I take my hat off to him for working out that technique [referring to Van Halen’s pioneering of the hammer-on technique]. You know, you talk about what I’ve done on the guitar and that’s what he’s done on the guitar. As far as it goes, it’s an incredible technique for what he does. I must say that. I can’t do it. I can’t smile like him either. It’s a really good technique but as I said I can’t play like that. That’s what we were talking about earlier: we’re talking about extremes now. That’s what’s so good about guitar players.

I was just curious if you had heard what he’d done with the tremolo or were familiar with his records.

No, I don’t even know what it is you call this thing he does.

Hammer-ons.

Hammering-on with the right hand? I’ve heard that but as far as his tremolo arm work goes I don’t think it’s that different from anybody else’s within the context of a solo. Anyone who plays a Stratocaster—although I know he doesn’t play a Strat—is going to tend to sound like that. I’ve only seen their videos and you have to remember that we don’t have MTV in England, as far as seeing people and what’s going on.

On the radio at the moment in England, all you would hear, I suppose, is Top 40. All those sort of synthesizer bands. So you don’t hear guitar a lot really. You don’t. Certainly not when you’re talking about somebody like Van Halen or anybody else you care to mention from America. If I don’t have the record, I don’t have a chance of hearing them in England. When you’re in a situation like you are over here, you’re used to seeing MTV and hearing fine music on the radio stations. It’s difficult to really put yourself in another situation—of course, you get video shows on television—but nor to the degree you do over here. Actually I’d like to do a market research and see how many hours of videos you get per week. I bet you get 30 minutes of them per hour. So consequently, I don’t get to see what guitars people play and everything else.

I would imagine that the studio would be some sort of playground for you?

No. The thing is, for whatever I did in production, the equipment I used I knew what to do with. But there was a whole time I was out of the studio, out of the recording situation for possibly three or four years, and things started moving very fast [snapping fingers] as far as the technology of things went. And whereas maybe I would link two or three pieces of equipment together, now you could just push one button and there it is. I mean I had an automated console and that sort of thing prior to going in with Julian Mendelsohn [an engineer who has been working with the Firm], but I just really wanted to see what [the studio] was like and check it out.

Was it a learning experience for you?

Yeah, a lot actually. To be honest, as far as the new concepts in recording, he used the automated console and linking up effects. That was pretty much the way you would have done it in the past, except there’s so many new things you don’t know. As I said, I haven’t been in the studio for years; I know it sounds crazy but it’s true. But nevertheless, it’s knowing how to wire one thing into another. And I would like to have been—and I haven’t yet—laying down some of the recording with a Synclavier. I would just like to see how it works—I’ve never actually used one.

But you have done a let of playing on the Roland guitar synthesizer? The Death Wish II soundtrack?

Yes. Given a situation, I’ve tried to get the most out of the Roland guitar synthesizer. Both versions but the second one [GR-700] was a better one. As far as it goes, I must admit that I went with Tim [Marten, guitar tech] to a demonstration of the SynthAxe and it was just absolutely terrifying. It was great, it was fantastic. I knew that the Roland didn’t track properly but you can adapt to it in a way. But it’s life and limb, really, to get one of those [synthAxe]. I’d have to sell me Les Paul. It’s just that it’s so expensive and all that sort of stuff. But it’s just like when synthesizers first came out, it was a fortune for nothing. It was just monophonic but you could have a polyphonic keyboard with whatever tone and triggering you were getting from that synthesizer for like ten percent of the price. So, do you see what I’m saying about the guitar synthesizer? I could see the difficulty in getting a string to trigger. It’s difficult because they’re touch-sensitive like a keyboard. That is always going to be the problem with guitar synthesizers. But as far as I can see, this SynthAxe is the best.

It’s very interesting, actually; its neck is at a different angle. I haven’t actually had a chance to play on it and get used to it. And of course, you have to get used to all the guitar synths, as such. I was so impressed with the demonstration of the SynthAxe that it’s difficult to even see what faults it might have. You need to have one to know. And I’m not going to knock Roland.

When you were approached to write the soundtrack for Death Wish II, did you think that would be a chance to work closer with the guitar synthesizer?

I thought it was quite a luck of timing to have the chance of doing that film music. As far as it goes, you’ve got visual and vocal sequences that you are asked to put the music to. And you’ve got your cues and everything. But if you’ve seen it a couple of times you get an atmosphere about what is going on and you just work accordingly. I didn’t purposely just want to use the guitar synthesizer but in certain places it just worked with that. Actually Death Wish II was about the most I’ve used the guitar synthesizer.

I know that instrumental music has always held a fascination for you.

I probably feel more at home with just instrumental music. Of course I do. I do hope to be part of something; it’s nice to be a catalyst in a situation or whatever complements the situation as well. But let’s not get totally philosophical about it. But seriously, that is it.

You did the music for Lucifer Rising [a film by Kenneth Anger]?

Yeah, but you don’t have to hear that. That’s alright. It’s not that good.

Does the guitar synthesizer make you play in a different way? Do the sounds trigger ideas in you?

Well, of course it does. It’s just like what I said about the StringBender; within the scope of the guitar, if you start to use it you come up with things that you build around it. Whereas, with the guitar synthesizer, as I’ve learned them anyway, it comes to the point where you do virtually work with what you’re getting out of it.

There are problems with them and I’ve said that. You can re-adjust the sound and whatever but I’ve not heard or played one yet (and I must admit I haven’t played the SynthAxe but I’d really like to) that I’ve really liked. I remember when the ARP came out, you’d have your manual out and you’d go through the instructions. And you’d set it up and it would say: “Possibly it’s your technique or possibly it needs to be and back to square one again. You went around in a circle and it was $1,500 for junk really.

However, the day when you can get $1,500 worth of good guitar synthesizer which is relative to keyboards, the guitarist will be able to kick ass on the keyboard players. But at the moment I can’t talk about the SyntheAxe because I don’t know it yet. But I must admit that seemed the closest to what the keyboard players could do.

[Tim Marten, sitting quietly in a corner, offers: ‘‘It’s not really like a guitar, is it?’’]

It is, that’s it. It’s like taking a new thing up, a pedal steel or whatever.

[Marten adds: “It may be what it’s like to play a keyboard”]

Quite possibly, I don’t know. I will remember that but I don’t know until one’s approached the darn thing. The neck is a different angle and it’s symbolic within itself.

When we talked last (in 1977 during Led Zeppelin’s North America tour), you spoke of the “guitar army” where you built guitar tracks in a classical fashion. To my ears, you’ve carried on with this style in the Firm.

When you say “in classical fashion,” that’s just orchestration. Guitar overdubs is really what it means. It’s just a more flamboyant way of putting it [laughter].

I had a chance to talk with Chris Huston (engineer) and he spoke of your ability to overdub, and the energy of Led Zeppelin II.

I was into ambience on the first album, I’ll tell you that. I was into it on the first album. Hearing drums sounding like drums. And that’s all there is to it. If you close-miked them, they sounded like cardboard boxes. Distance makes depth. If you take the mikes up you get more of the sound. He was the resident engineer at Mystic Sound and it had wooden walls, so consequently it’s going to bounce [claps hands] and sound live. Ambience ... it was a small room. Richie Valens [“La Bamba"] recorded there. Bobby Fuller [“I Fought the Law”]. If you listen to “La Bamba,” for instance, you listen to the overall sound of a room where they were recording. You know? You can hear it. Which is what it’s about I think anyway. Even if you’re using multi-track, it's still down to trying to capture that.

Let’s put it this way, when you listen to the records of the Fifties, there is a room sound there. It’s obvious; they were recording in tiny rooms. Like garages. But the overall energy of it comes through. There’s no doubt about it.

Chris Huston said in those days making a record was more simply just trying to document a performance.

He said that because he only did a few tracks with us; he didn’t do any mixing or anything. So I don’t know what his idea of looking at things is. But as far as I see it he’s saying it’s documenting. Well, sure it’s documenting a sentiment, an emotion. It is documenting a performance but you can make yourself sound very bland by that. But that’s where you were at that point in time.

Your guitar sound on the second album was really extraordinary but it was quite different from the sound you got on the Mean Business album. Which goes back to something else we talked about in 1977 when you mentioned trying to achieve different sounds so you “don’t have the same guitar effect all the time.”

It’s very difficult but you have to try. The guitar to me, from the classical/gut-string guitar right through to Hendrix, et cetera, has all this range. Within those six strings it is incredible what one can get sound-wise. It’s just down to imagination, really. You were talking earlier on, relative to what I was saying, about how everyone sounds like Eddie Van Halen. He worked out his own technique on the guitar and it’s just down to the imagination. Obviously you have to have the technical ability because there’s a lot of times you have the imagination to do something but the technical ability may not be there.

That’s where the discipline comes in. From the classical guitar right through to the furthest electrical experiments and everything in-between, it’s amazing what the guitar can actually do. I mean, when one thinks about sounds, I’ve gotten sounds out of the guitar with a bow where there was no other way you could do it. It’s still the six strings and it’s very basic—just applying a bow to the guitar.

At times, the sounds you create with the bow and the wah-wah [his main effect during the hewing sequences] and the Les Paul seem to be generated by a guitar synthesizer.

Yeah, that’s it. Except it’s immediately controllable like that [snaps fingers] with a wah-wah. Obviously it’s a hit-and-miss approach sometimes with the bow—it doesn’t always react if there’s humidity in the hall, which is a bit of a drag but you can keep rosining it [the bow]. Obviously, it’s not an arched neck like a violin or a cello, but sometimes you can come close to hitting a full chord with it. And that’s alright. But if it’s a humid atmosphere, it doesn’t. I’ve never spoken to a violinist about it actually; whether the humidity can affect the rosin to the bow to the strings. I’m sure it must, though.

The Les Paul lends itself better to the bowing than the Telecaster or a Stratocaster?

It works on them all, really.

[Tim Marten interjects that it relates to the ‘Physical aspects of the curvature of the bridge.” To this end, Marten sawed the Les Paul bridge to create a more violinesque-type housing and raising the strings to allow for more accurate bowing.]

Yeah, he did that. And it was purely because it was so hit-and-miss. Sometimes it would be dead on and then you wouldn’t change a thing and it wouldn’t work. Last night [referring to the Firm's performance at the Ocean Center in Daytona Beach, Florida] I didn’t think it came off at all. Not as well as it should have done. It’s almost like pulling at it and that’s alright but when the bow just goes right across the strings it doesn’t work. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t—but you’ve got to try it.

The sound that you have created with your Les Paul...

And what about Eric? That’s where it started.

I know. You talked about that in our last interview. But I feel the sound you’ve produced is, for want of a better description, classic.

What about Jeff Beck then?

And Jeff is there, too.

Fucking, he better be. I’ve heard so many guitarists sound like Jeff it’s not true. Which is great, you know? That is Jeff, that is Jeff’s personality, and people relate to that. They’re emulating it, not imitating. But that is a classic. Van Halen, with what you said, created a technique which is totally personal and if anyone wants to follow along with that they can. But it’s still Van Halen’s technique. You’re talking about a sound but nevertheless that sound is very tactile.

All I’m trying to say is there are a few guitarists like Beck and Clapton and Van Halen and when you say people emulate someone like Edward.

I didn’t say emulated Edward, you did. I didn’t say that at all, you did. Do you want to run the tape back and check what I said right now? What I said was with Jeff’s sound. Do you want to turn this off right now or what? Because I can go through it again.

I wouldn’t write down anything you didn’t say. I just made a mistake.

No, listen, I don’t care what you put down, I want you to try and lift things up. What I’m trying to say is you’ve got so many guitarists who come to the forefront as figures like Jeff, and Edward, obviously you being a great friend of his, and McLaughlin, all of them. But the ones who you immediately think of when you say “guitarists” and if you’re hard-pressed to come up with names, these are the people you’ll think of. And if you’re playing guitar at home, one of those may be the guitarist you relate to. So when you say “classical” I don’t know whether you meant Eddie Van Halen or what? Classic, maybe, not classical.

I feel that guitarists from the late Sixties had such unique styles and were so easily identifiable.

Yes, of course. It occurs to me that contemporary guitar players haven’t done anything that hasn’t already been done. That is where the guitar synthesizer might come in but I wouldn’t take it on. But there is far more sensitivity in acoustic guitar players than could ever be compared to any synthesizer. No way. That’s a personal point of view but that’s the way I see it. I think that’s what it’s all about. The drive, the fire, the passion—it all comes out on the guitar.

Do you think guitarists in bands like Ratt and Motley Crue show sensitivity? Do those names mean anything to you?

Yeah, I’ve heard the names. I saw one Motley Crue video the other night. Someone asked me once about Van Halen and I didn’t know if it was a group or what and they said, “Oh, you’re kidding? You’re putting me on?” And I said, “No, I don’t know, I’ve never heard of them.” This was in England and a radio interview and it wasn’t until much later, “Jump” and all that business, that I heard of them. This was three years beforehand. Mind you the guy did say, “Do yourself a favor and go and buy his album [laughs].”

I can only pass comments on what I’ve really sort of heard. And it’s not fair to do so if you don’t. And that’s the truth. I just wondered when you asked me the question about Van Halen if you knew what I’d said on radio. That was said once and if you thought I was putting you on, I wasn’t.

I only asked you about Van Halen because he is a friend...

Well, I told you that…

... And I think he’s an extraordinary guitar player.

He is. He’s developed a technique which is really good. As far as pushing the guitar onwards, yeah, great. That’s what it is all about.

Moving on to other things, was the ARMS show in fact the first time you and Paul Rodgers performed together?

Yes, absolutely.

Was there an intention at that time to put a band together?

No. I didn’t have a singer and I needed one and it was like an SOS really because Steve Winwood was singing at the Royal Albert Hall show in England but he wasn’t coming to the States. So there I was without me fig leaf, so to speak. I had played with Paul a few times at his house, we had a couple of jams. I had been to his house and there were these bits and pieces but that was well prior, six or nine months prior, to the ARMS thing.

Were you nervous appearing at ARMS after not having played for so long in public?

That’s an understatement. Of course I was. I was terrified but I wanted to do the whole thing. It was funny because I said, “Yeah, I’ll do it, I’ll do it, yeah, great!” but at the last moment I thought, “Oh, God, what am I gonna do!” It’s the truth. It’s funny but it’s true because everyone else had notable solo careers. Like Steve Winwood, fuck, he’s had enough solo albums, and Eric, and Jeff [starts laughing]. But the fact was everyone was working so tightly together. Not for themselves but for the cause of it which was great. I’ll tell you, I don’t think any promoter could get those three guitarists doing that. Do you know what I mean? But for the right reason they’re there.

Did it feel good playing with Beck and Clapton again?

Oh, yeah. Yeah! The three of us have never played together. We’ve never played together as the three of us. I’ve played with Jeff and Jeff has played with Eric and I’ve played with Eric but never the three of us.

Does the fact that you brought back “Stairway to Heaven” at the ARMS concert say that you saw it as one of the more important pieces of music you’ve written?

I wouldn’t bring it back because I consider it’s always there and not just purely as a vocal number. As a piece of music and as far as my writing end of it—absolutely. But the lyrics are as important as the music so it’s a really a fine fusion between the two things. The fact is, when you’ve got twenty or twenty-five minutes of music to come up with in that ARMS thing, I didn’t really have anything. I was certainly not going to turn my back on the past as such as far as my own personal contribution went. If we had known at that time that it was going to be Steve Winwood in London and Paul over here I wouldn’t have insulted anybody by mentioning it. But if you can see it as the fact of someone singing it, yeah, sure, it would be absolutely wrong. But just by playing the music on the guitar I thought it was the right thing to do.

Did you ever have any sort of desire to pursue a solo career as such? Maybe make a solo record of hits of music you had been collecting over the years?

Yeah, I know what you mean. Yes, now. But you see you’ve got to realize, I was with Zeppelin and as far as my end as a guitarist, the dream was to play with those sort of people that are that good and everything seems to be going on. Ever onwards and outwards. But I think when anyone forms a band or is part of a band. . . it was a privilege to be part of Zeppelin, obviously. I know everyone would say they were part of that. And the chemistry was so good.

How did Live Aid feel?

Hmmm, OK, well... [smiles]. Live Aid felt like one hour’s rehearsal which we all had after not having played together for seven years. [Page exaggerates the time period, it was closer to five years]. But it was great to be part of it, really. At one point I was almost forgetting why I was really there. I was so worried about forgetting this chord and that chord because I hadn’t played the numbers for years. But to be part of Live Aid was wonderful. It really was.

And you mentioned that you had been doing some writing with Robert?

Yeah, we have been. We’ve been playing together, yeah.

What does it feel like?

Well, it feels like playing with old friends so it’s good. It’s good therapy, too, because everyone is in their own direction one way or the other. Well we all know everyone is into different things. And it was interesting. I must admit at first it was kind of odd. Not odd but a big smile and slightly tense the first day. The second day was great and we were all close together. It was great, fantastic. You’re talking from the last time we played it’s been years.

How did you like the Honeydrippers record?

It was good. I think it’s good for you to do that sort of thing. Robert sings that sort of thing good and he’s really at home in that sort of music. And he sounds good, too.

And what about John Paul Jones’ solo album?

Scream for Help? I haven’t heard the record as such but he’s quite an amazing musician when he’s writing that classical stuff. He has an Arts Council Grant to do so. I mean he was telling me about some of his ideas and what he was going to do and it was fantastic, brilliant, as far as that goes, but he’s a rock and roller. If his record just came our recently, we’ve been on the road pretty much all the time and I haven’t had a chance to get it. But if it’s the soundtrack for Scream for Help, which I presume it to be—it was really good. Varied writing, which is really great, and it shows how he is on the synthesizer.

Obviously, Coda was not the last album you wanted to make with Led Zeppelin.

Of course not, no. But if you knew how many bootlegs there were out on Zeppelin, those were the only studio tracks that were left. Actually there were some tracks that weren’t on because they’d gone actually [laughs]. Good tracks. They sort of disappeared in New York or somewhere. But those were all the studio recordings left from amassing all the Zeppelin tapes. And that’s only relative to the bootleg situation.

And what about In Through the Out Door, the last real Zeppelin studio album?

It was the last album as such where we were all together in the studio to be playing. What can I say? It’s a tragedy that John Bonham passed away. I think that at that point in time In Through the Out Door could have been a very interesting transitional stage to what would have been happening after that. I think it really would have been interesting to see what came after that. But I don’t know, maybe we would have split up. I don’t know, I don’t think so.

Does any of the music of the Firm contain bits and pieces that you may have written for Zeppelin?

Oh, of course, everything. Of course because that’s me. To have been part of a band like that and limited within what our boundaries are, I know what my limitations are—you’re pushing yourself nevertheless all the time. So I would say yes, of course. By pushing yourself all the time, you’re putting your own character into that band. And that is it. You’re still pushing onward [referring to the Firm], but you’re still identifiable as yourself. Do you know what I’m saying? You can hear Paul’s voice and you know it’s Paul. It’s the same thing when you hear Eddie Van Halen—you know it’s him.

That’s the only thing I can do in life is play guitar. It’s a commitment to the guitar.

Did you read what was written about Zeppelin in Hammer of the Gods?

No; I read bits. I couldn’t read it all through because it was crap. What did you want to know about that?

I was just curious if you’d read it and what you thought about it?

Well, it’s someone trying to make a buck out of Zeppelin, isn’t it?

In your conversation with William Burroughs years ago in Crawdaddy, you talked about laser notes which “cut right through.” Do you think you’ve managed to play any of those notes over the years?

Thanks a lot [laughs]. That was a good idea at the time but I don’t know about now. I remember that actually; that was great meeting William Burroughs.

I think you’ve probably played one or two of those notes at one time or another?

Maybe, yeah.

Does making videos as an art form appeal to you?

Making them, yeah, but not appearing in them. I like the idea of it. I don’t know how to explain [to someone else] the techniques of it. I can’t even mime the bastards properly and that is a drag [laughs]. But all I can say to you is if you’ve seen ZZ Top’s latest one [“Rough Boy”] then you could see how I’d say to somebody, “I have this idea but I don’t know how it’s done." There are techniques which I’ve been away from for a long time and I wouldn’t know. I’m determined to find out how some of that [ZZ Top] video was done.

Are you a fan of ZZ Top’s music?

I think that’s what rock ‘n’ roll is all about. They really are incredible. They have great music, really fine playing, really solid, and they have a sense of humor as well. They’re damn fine. And everyone is enjoying it and they’re enjoying themselves. As far as their videos go, every one has been a winner, hasn’t it? But I must admit I haven’t had that much to do with videos.

Talking about the new album, it sounds like Mean Business has more of the drama, that dark side of the Zeppelin music, than the first Firm album had. The first record seemed a bit more tentative.

It would appear like that in retrospect, yeah. Yeah, it would appear like that—but it wasn’t. The material is a lot stronger on this album. And then again the band had been playing together for at least a year prior to doing it. I must admit it would have been good to have done certain tracks on that first album again at that point but that’s all I’d got. It’s a statement of where you are at that point in time.

Were you looking for a certain kind of rhythm section for the band? When you heard Tony Franklin and Chris Slade did you know they were right for the band?

I wanted to get a couple of hooligans, yeah. They’re good guys and damn fine musicians [bassist Tony Franklin had been playing with Roy Harper for the past three years and it was during a Harper gig that Page and Franklin met; drummer Slade has played with an array of bands and on the same day he received the call from Jimmy he was phoned by David Gilmour for his solo tour—he was determined to undertake both ventures and he did].

The fretless bass is an interesting texture.

Oh, Christ, yes. Tony is amazing. Watch out for Tony because he’s a fine musician and a fine writer. A couple of years and everyone will know what it’s all about.

Is it true you were also interested in Pino Palladino [Paul Young’s bassist]?

That’s right, yeah. Purely because he and Chris had played together before.

Without trying to be too inquisitive...

You can be as inquisitive as you want in the right areas providing you only print those areas.

OK. Is there any other information you can give about your work with Robert Plant and John Paul Jones?

Well what do you want to know?

Will Led Zeppelin get together?

Is that what you wanted to know? OK, fair enough. The guys, the band is getting back together and playing maybe every six months or every year. That’s all. If I can do so without it being public knowledge that would be great. But I can’t do it obviously. That’s the truth, too. It’s so difficult or it appears to be. It would be nice to play together just as friends.

Or maybe just make some music together.

Just as friends, that’s it. I mean, who knows? I think everyone has their own thing going on separately. If you’ve had a friendship in the past, there’s no reason why you shouldn’t get together. I played with Robert in the Honeydrippers thing and I’m playing with John on the Scream for Help album. So why not? Why shouldn’t the three of us get back together and see what happens? And have a good smile at the end of the day, hopefully, and that’s it.

I get the impression that you would have felt comfortable as a street musician on some corner, say, in Morocco.

Maybe not quite on a street corner or whatever, but certainly to a degree where you could have a play somewhere and not have a big hoohah follow you. Just to be able to have a play with other guys and not have a to-do about it. That’s relative to a street musician and minstrel singers as well.

I just started playing the guitar. If I’d never played the guitar I’d probably be a juvenile... well, I wouldn’t be a juvenile delinquent at 42, would I? I don’t know what would have happened if I hadn’t played the guitar. Mass murderer.

Do you practice the guitar?

No, I couldn’t do that. It’s usually the acoustic guitar for a start and it’s usually in a tuning. I sort of change tunings around a bit and I’m searching for new chords and shapes and things. I don’t just sit down and play scales and things. I should have done but I never did. I can’t play a scale. You think I’m kidding but I’m not. I can’t. Well I can, I can play the notes but it’s true though. I can’t play a bar chord. It’s true. It’s unbelievable, isn’t it [much laughter]? It’s true though. It’s just try to do whatever you can do on an instrument and give it 100 percent of what you can do with the time you have to do it. I push myself as far as I can go within the instrument at that point in time.

You’re not the type of player who would take a Floyd Rose and put it on an instrument. Rather, you’d work with the stock mechanism, as an example, and make that work for you.

What’s that [referring to the Floyd Rose]? Is that one of those things where you can’t change the string if it breaks? I don’t have one of them. Whatever guitar you’ve got, at that point in time you work it so it’s right for you. It’s like a marriage, isn’t it? I think so. It’s therapy.

Do you have any interest in producing other bands?

Yeah, well I wouldn’t mind. If I felt comfortable in the situation, yeah, sure. If it was something which really grabbed my imagination, sure I would.

Do you feel that you could continue working within the Firm and working with Paul? Are you comfortable musically?

Yeah, I could continue playing with Paul, sure. All of us, I’m sure, will have our own solo projects. Obviously, Paul has made solo albums before and I’ve got a few projects I want to do. Not singing. I won’t talk about it. I think the best thing to do is not talk about it because usually when you outline ideas sometimes they don’t come off. It’s a pipedream. But it might be playing the guitar as such, instrumental stuff. But I don’t want to outline some of the ideas because they might sound far more interesting than what they may really be.

Would you mind talking about some of the specific tracks from the albums? What are the effects you’re doing at the beginning of “Cadillac” [from the Mean Business album]?

What do you want to know? The effects at the beginning? It’s trying to make the guitar sound as dirty as fucking possible, that’s what it’s trying to do.

[Tim Marten offers. “The strings are slack and then you pull it up (imitates ascending in pitch).”]

As far as that version of “Cadillac” goes, we were lucky to get it because it was a live number and you can’t do that in a room with a couple of takes because it has to be live.

The second Firm album was recorded after the band had been on the road and the second Zeppelin album was recorded...

... while the band was actually touring. [Lifts sheet of questions from the table and pauses while interviewer changes tape and interview winds down]. We were on the road and it was during the first couple of years of the band. There’s going to be a different type of energy relative to touring. But I think there was an energy on the fourth album and Physical Graffiti and whatever. You talk about the energy on the second album, what energy is more important than “Stairway”?

[Page is looking over the questions].

I’m just trying to tie up the loose ends.

Does the first Firm album hold any of the emotion that the first Zeppelin did?

Obviously, there was an emotion as far as my end of it went but, as you see, it may not be as intense as far as the reception of it. But, nevertheless, it’s exactly the same emotion.

On the first album you cover "You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling.” Was Phil Spector’s music something you listened to?

Yeah, but I’ve never met him. We went to Gold Stone once with Zeppelin, which is where he recorded. It was amazing. It was as funky as you’d expect it; it was fantastic.

Did Motown hold that attraction for you?

I think Motown had that attraction for Phil Spector, didn’t they? Popular classics really.

You obviously liked what Les Paul did [there is a picture of Page and Les Paul in a glass frame sitting on a shelf in the hotel room]?

More than anything I appreciated enough of his playing, but to meet him and see how natural he was was amazing. Apart from the fact he’s a genius, he’s such a warm person. I’ve never had the chance to actually play guitar with him at the same time. I’ve been to his house and we’ve had a chat. He’s the father of everything.

And he made the first headless bass.

Yes, he’s incredible.

Would you ever bring the theremin back?

No, I don’t think so. Come on, last two questions.

Do you plan to make another Firm album following the tour?

I don’t have any plans at the moment.

OK, that’s great. Thank you so much.

OK? That was only one question.