All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

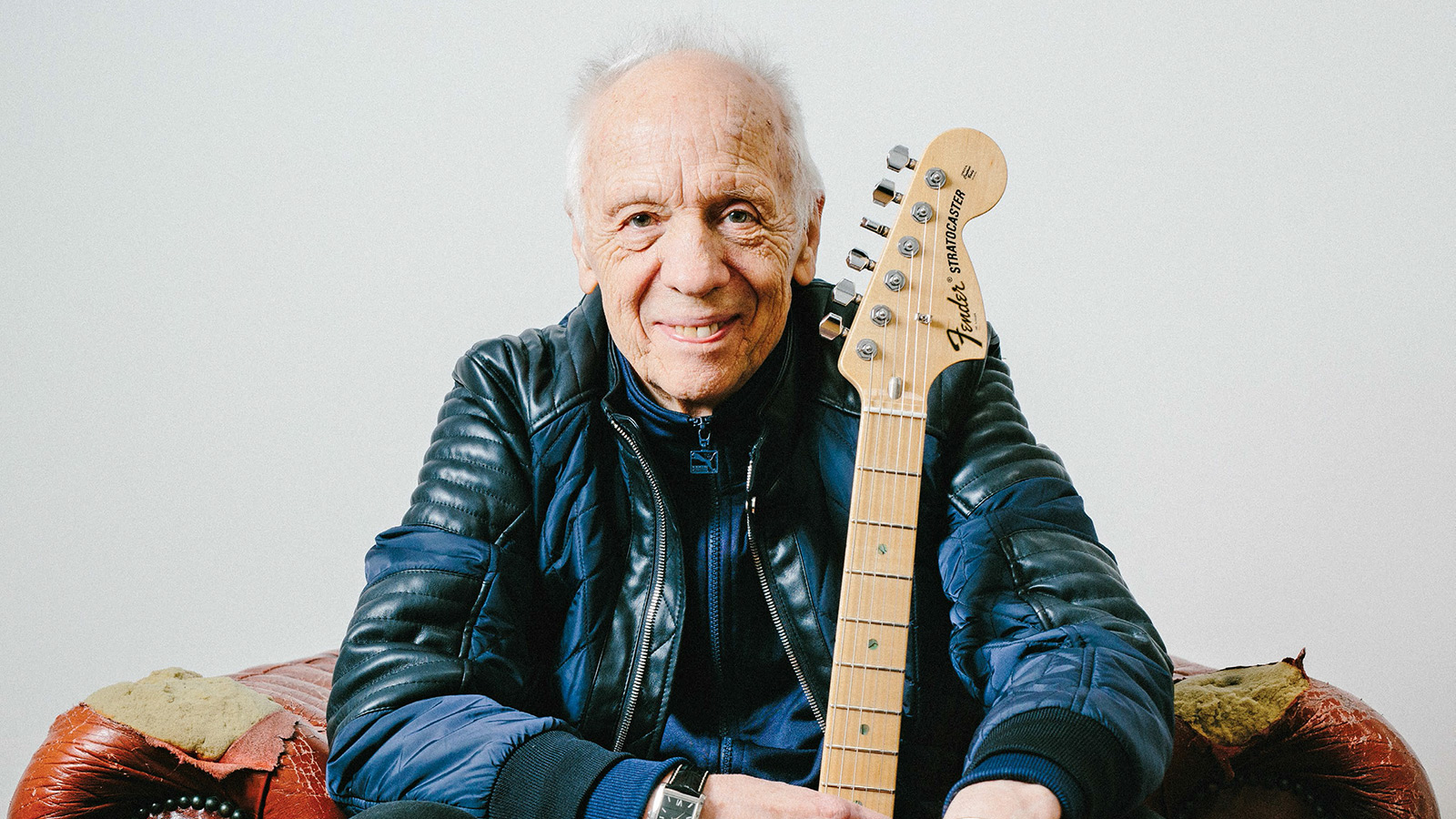

"Musicians of my generation had the best of times,” says veteran British guitar master Robin Trower. “I look around now at how the music business operates, and I would hate to be a young guitarist trying to get heard. There’s so much out there taking up people’s attention, and that’s the problem — nobody’s paying attention. When I was coming up, there were just a few radio stations. If your record got played, you were in. You became famous, and you were making money. It was fabulous!”

He pauses reflectively, then adds, “Of course, we had to get lucky to score a record deal, but even so, we had it better than new bands today. They have to get really lucky to get anywhere. I don’t know how they do it. I feel very fortunate to have come up when I did.”

Fortune smiled on Trower early on in his career. In 1967, thanks to a brief stint in the R&B covers band the Paramounts, he was seen as one of Britain’s hottest young guitarists. At 22 he joined the pop/progressive rock band Procol Harum right as they were invading AM radios everywhere with their moody, classical-meets-soul debut single, “A Whiter Shade of Pale.” Although Trower didn’t play on that cut, he made his presence felt on six of the band’s albums during his four-year tenure with the group, and his forceful, Strat-driven, psychedelic-tinged blues solos quickly spread his name across the globe.

“Looking back on it now, it seems like such an incredible time,” he says. “You had the Stones, Cream, Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix, and we came out in the middle of it all. There was this explosion of talent that will never happen again. In retrospect, you’d call it a musical renaissance, but the funny thing is, we didn’t think anything of it. It all seemed so natural. We weren’t really thinking about it. We were just doing it, you know?”

After leaving Procol Harum, Trower embarked on a solo career that has proved remarkably sturdy, recording a staggering 22 albums that count among them a fair number of classics, such as Bridge of Sighs (1974), For Earth Below (1975), In City Dreams (1977) and What Lies Beneath (2009). Along the way, he teamed with bassist Jack Bruce and drummer Jack Lordan for the short-lived band B.L.T., and he even loaned his talents out to singer Bryan Ferry for a trio of albums between 1993 and 2007.

Trower is 74 now, and he admits it’s a funny age to be. “You spend a fair amount of time thinking about your past,” he says. “Let’s face it — I have a lot more years behind me than in front of me.” He’s called his newest album Coming Closer to the Day, but he insists there’s nothing morbid about the title. “I’m not thinking about dying — far from it. What I’m saying is, ‘If I’m nearer the end than the beginning, then I’ve got to get going.’ So many people my age back off the pedal and coast, but I’ve got no time for that. I have to work harder than ever. In terms of writing and playing the guitar, I want to do my best work, and the time for that is now.”

As he has done on his past few albums, Trower played all the instruments on Coming Closer to the Day except for the drum tracks, which were handled by the guitarist’s longtime sticksman, Chris Taggart. Whereas his last disc, 2017’s Time and Emotion, was built around structurally adventurous compositions, the new album features leaner and tighter arrangements that offer cleaner canvases for the guitarist’s unbridled soloing. “I go back and forth sometimes in how I write,” Trower explains. “Sometimes I think people want more from a song than just the sound of my guitar, and other times I say, ‘Well, I’m a pretty good guitar player, so I should just have at it.’ The key is to marry both worlds — good songs and good playing. That’s always been my objective, and I think I’m coming along.” He laughs, then adds, “And I can always get better.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You say you can still get better on the guitar. I’m curious — at this stage in your career, what do you need to improve?

Well, I don’t know if I can be specific about that. The thing is, with every new song I write, I need to come up with a certain way to play the guitar that suits the music. That’s what’s so fascinating about the guitar — those new wrinkles that occur as you play. It’s not like I sit down and say, “I’m going to learn something new today.” A lot of times, it happens by accident. But you won’t have those accidents if you don’t play a lot.

During the Seventies, you were compared to Jimi Hendrix quite frequently.

I certainly was.

Did you ever find it funny that writers never mentioned B.B. King? You often cite him as your biggest influence.

That was strange, yes. B.B. King completely changed the way I looked at playing the guitar. Before I heard him, I was doing more of your stock rock ‘n’ roll playing — nothing bad about it, but it was pretty much like everybody else. B.B. came along and started doing these really soulful melodies with bends and vibrato. He was so expressive and creative. That really had a tremendous impact on me. And then I heard Albert King and Hendrix, so I absorbed their styles. Whenever I play, I can definitely hear the three of them — B.B., Albert and Jimi.

Several years ago, you said you found it hard to listen to Bridge of Sighs. You didn’t like the fast vibrato and how you were bending notes up. Have you come around to the album yet?

No, it still bothers me. I don’t listen to it, to be honest. There’s certainly stylistic things about the lead work that really annoy me. I know my fans like that record, but I just can’t get past that fast vibrato.

Do you think the way you played then was due to your young age? You were all high on adrenaline and out to prove yourself.

I think that’s exactly it. That high-energy style of playing was down to how young I was and I was all hyped up. At the time, I thought I was playing soulfully, but that’s all relative, isn’t it? That’s what I’ve been working on over the years, trying to make every note soulful. So now when I play material from that album, I try to adjust my vibrato and dig in more, without losing the potency of the music as it was written. My technique is quite different and much better now.

You’ve been playing the bass yourself on your recent albums. Why is that?

I just want the bass parts that I come up with. I could probably get a better bassist than myself, but I like my playing — it’s kind of dirty. I prefer the bass to be simple, but it’s gotta have that pulse. It’s more about feel than notes, and I know the kind of feel I want. I can’t explain it to a bassist, so I just do it.

Chris Taggart has been your drummer for some time now. How much leeway do you give him in the studio to flip your tunes around?

He doesn’t really change songs from the way they’re written. I always have a pretty good idea of what the beat is and what the fills should be. And Chris is very, very good at delivering what I want. He’s got such great feel. Sometimes he plays to a click track, but other times it’s us playing live in a room together.

Your guitar sound on record is as powerful as when you play live. Are you recording at full volume?

Oh, yeah. Volume is a big part of it. I never turn the amps up on high because then it starts to turn to mush. I would say they’re mostly on seven or eight. I like to play in front of the amps — you can respond better to what’s coming out of them. It can be a little overwhelming sometimes, so that’s when I’ll go into the control room and play. You want a loud sound, but if it’s uncomfortable that really affects what you’re doing.

Out of all your new songs, “Truth or Lies” is more R&B than rock-blues. Do you approach something like that differently as a player?

That’s an interesting one. It gave me a hard time in the studio — I had to cut it a few times to get the right feel. It is more R&B, but I didn’t want it to sound traditional; I still wanted to do my own thing with it. It wasn’t so much phrasing or note choices; it was more the weight of the thing, the overall feel. I wanted it to sound like “heavy R&B,” if that makes any sense.

You sound like you’re having a blast on “The Diving Bell.” In the second solo, you’re not going for melody, per se — you are poking and attacking the strings.

That was a fun one, yes. It was very free-form. I was just messing around but still trying to stay in the pocket. I don’t really plan my solos; I have a sense of what I want to do, but I don’t cut them on demos and re-create them note for note. Solos have to be spontaneous.

The title track is built around a simple recurring riff, but there’s sparkly little chord textures underneath it. Can you play both live?

Oh, no. I don’t think I could do that song live, to be honest. When it gets to the lead, you need those chord changes underneath. Without those chords, the whole thing falls apart. I decided a couple of albums ago that I wouldn’t hold back a track in its development just because I need to play it live. Besides, I have lots of good songs I can play on stage. I can’t do ’em all. [laughs]

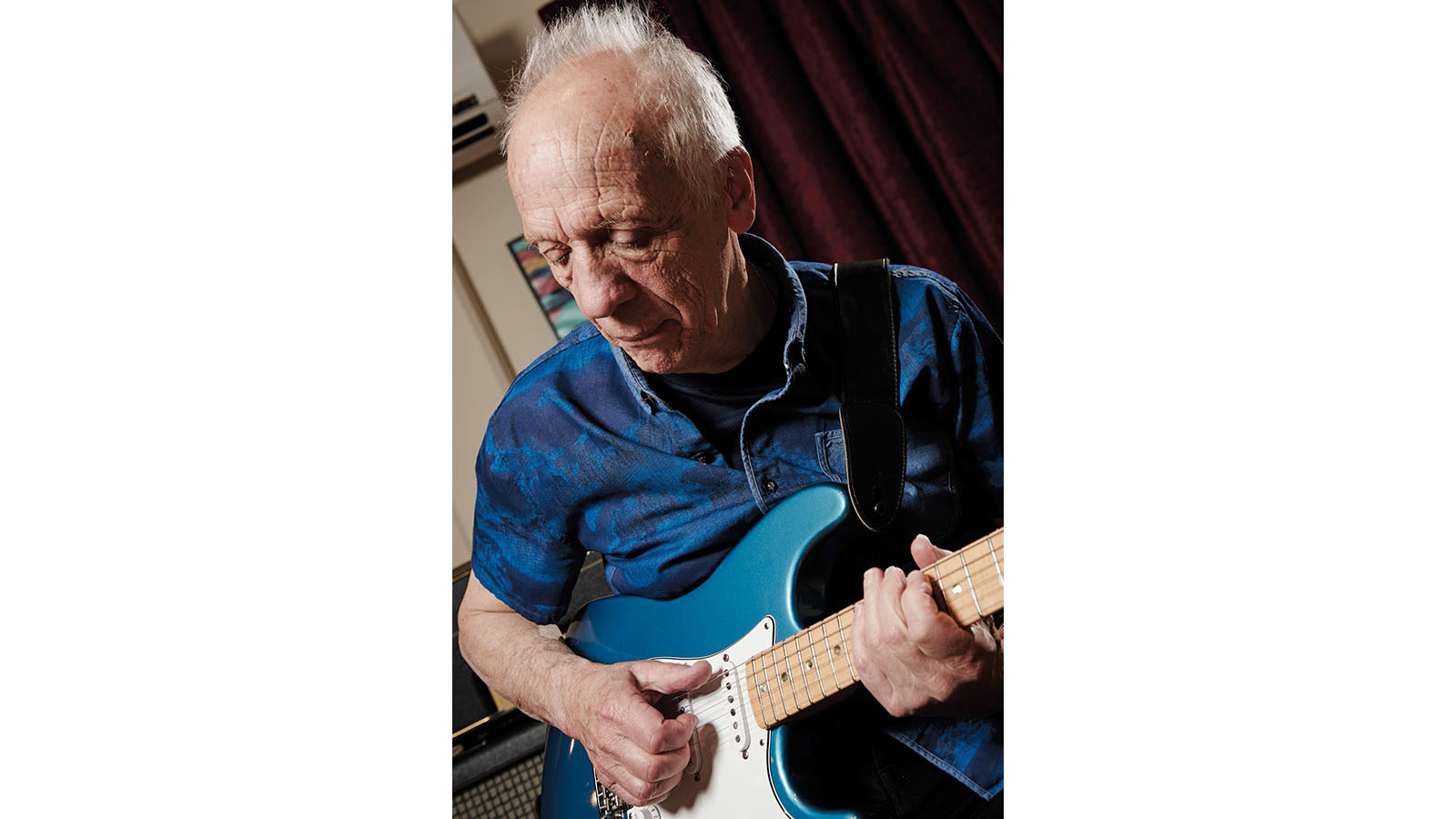

I probably don’t have to ask, but I will: Did you play anything other than Strats on the album?

Oh, no! No, they’re all Strats — my signature models. Why would I use anything else?

You never get the temptation to try out a different sound or feel? You never pick up a Tele or Les Paul?

I could, but the pickups in my Strats give me every tone I could ask for. I put a Strat into my own [Fulltone] Deja Vibe, and I get so many sounds. I’m quite happy with what I use.

Do you own anything other than Strats?

Nope. All Strats.

So if we went into your house, all we would find is Strats?

I think so. Oh, wait… I do have a Martin acoustic upstairs, but I never play it.

A couple of years ago, you started using Marshall ’62 Bluesbreaker combo reissues. Are you still using them?

I am, but I’m also using Marshall JCM 800s. I tried them out and thought they were extraordinary. I put those amps into Marshall 4x12s with [Celestion] Greenbacks — they’re great. The 800 is a very loud amp, but it’s got a such a sound. So I go back and forth between the combos and heads.

You come from a time when guitarists made such radical advancements. Is there anybody you’ve heard over the last 10 years who has made a real impression on you?

I must admit, I don’t really listen to new stuff. I don’t even know where I’d hear them. There’s so much out there — I wouldn’t know where to look. The guys I grew up loving are still my favorites: B.B. King, Scotty Moore, Cliff Gallup, Otis Rush, Jimi Hendrix. I admire Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck as players, but the music isn’t my cup of tea.

So you stick to what you know and love.

Kinda. Well, there’s Billy Gibbons. He’s not “new” new, but he’s later than the others I mentioned. I like what he does. But you know how it is — when you’re doing it, you don’t have time to listen like everybody else. I’m too busy playing to absorb it all. I guess if I stopped playing, I could spend more time to be a listener, but I don’t think I’ll do that anytime soon.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.