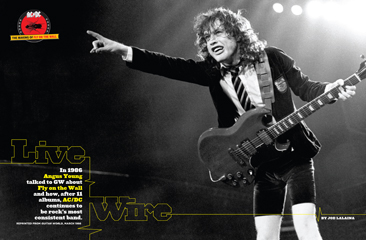

AC/DC: Live WIre

In 1986 Angus Young talked to GW about Fly on the Wall and how, after 11 albums, AC/DC continues to be rock’s most consistent band.

Before you even play the •rst song on any new AC/DC album, you know what to expect. Rarely has a band maintained such a consistent sound as AC/DC—they’ve been pretty much making the same album for the past 10 years. Fly on the Wall, the group’s eleventh release, is no exception. “I’ve heard people say all our music sounds the same,” says soft-spoken lead guitarist Angus Young, “but it’s usually just the people who don’t like us who say it.”

Not true. It’s just that ever since the band’s High Voltage debut back in 1976, AC/DC has been playing the same relentlessly raw and straightforward style on every succeeding album. And that’s the way their fans like it.

“We never go overboard and above people’s heads,” says Angus, who took some rare time out from his recent American tour to discuss musical and other matters. “We strive to retain that energy, that spirit we’ve always had. We feel the more simple and original something is, the better. It doesn’t take much for anyone to pick up anything I play—it’s quite simple. I go for a good song. And if you hear a good song, you don’t dissect it—you just listen and every bit seems right.”

Although this stripped-to-the-bone approach has made AC/DC internationally successful—thirty million albums sold worldwide ain’t bad!— Angus is more concerned with having a good time than with album sales. “We don’t go around the world counting ticket and record sales,” he says, “nor do we glue our ears to the radio to hear what’s trendy at the moment—we’re not that type of band. We do run our own careers, but we leave the marketing stuff to the record company. We make music for what we know it as, and we definitely have our own style.”

Is there anything Angus considers special about his playing style? “In some ways, yeah,” he says. “I know what guitar sound I want right away. And if I put my mind to it, I can come up with a few tricks. I mean, I just don’t hit the strings that my fingers are nearest to. But the most important thing, to me, is I don’t like to bore people. Whenever I play a solo in a song, I make sure that the audience gets off on it as much as I do.”

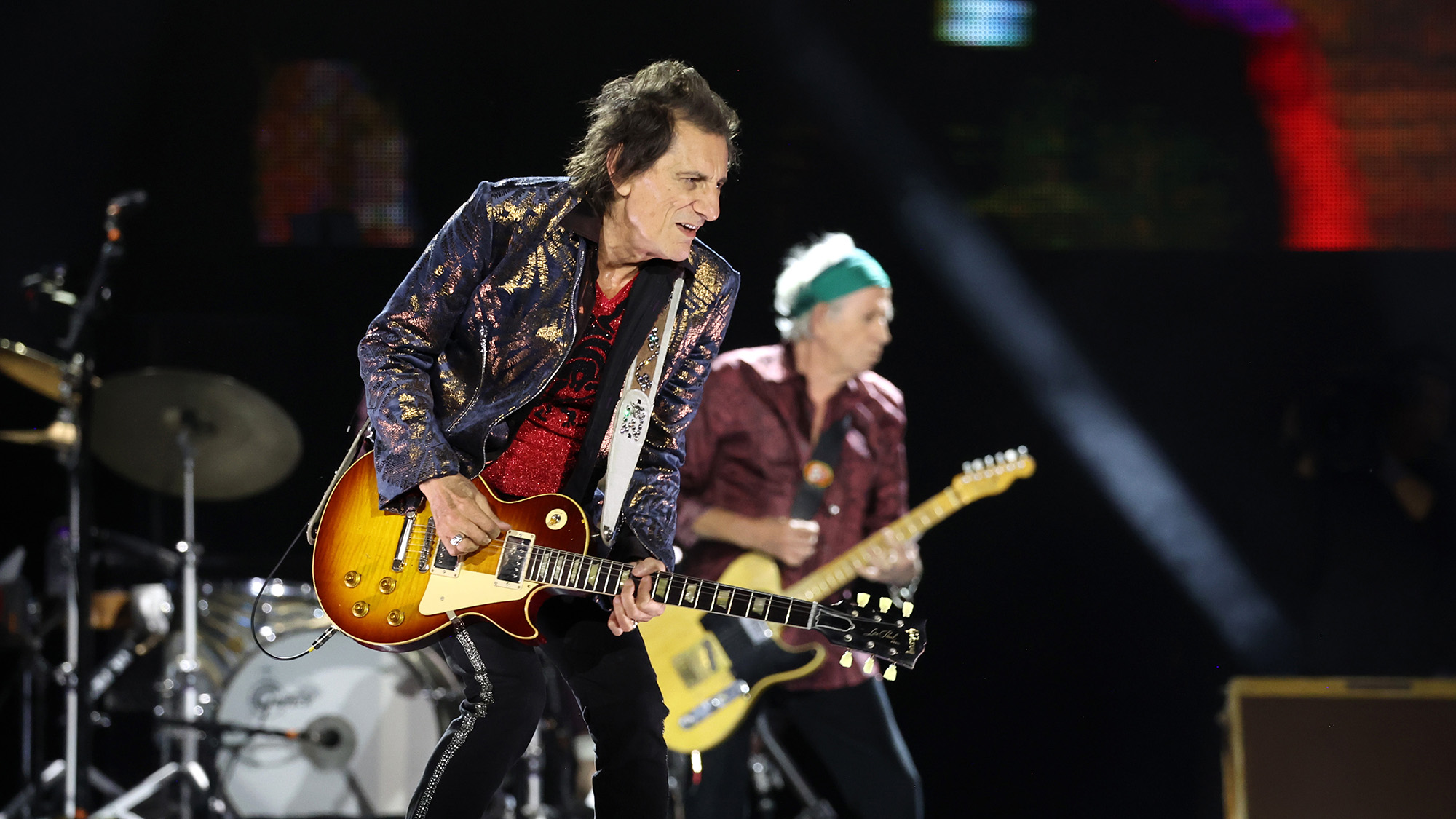

Angus exerts more energy in the course of one song than most guitarists do in an entire show. “I’m always very nervy when I play,” he says. “I usually settle down after the first few songs, but it’s hard for me to stand still. I suddenly realize where I am—onstage in front of thousands of people—so the energy from the crowd makes me go wild. I’m always very careful, though. If you bump an arm or twist an ankle, there’s no time for healing on the road. You can’t tell the crowd, ‘Hey, people, I can’t run around tonight, I have a twisted ankle.’ ”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Malcolm Young, AC/DC’s rhythm guitarist and Angus’ older brother, would rather just stand in one spot and bang out the beat with thuddingly repetitive chord structures. “Malcolm makes the band sound so full,” says Angus, “and it’s hard to get a big ego if you play in a band with your brother—it keeps your head on earth. Malcolm is like me—he just wants the two of us to connect. Although he lets me take all the lead breaks, Malcolm’s still a better guitarist than Eddie Van Halen.

“Van Halen certainly knows his scales, but I don’t enjoy listening to very technical guitarists who cram all the notes they know into one song. I mean, Van Halen can do what he does very well, but he’s really just doing finger exercises. If a guitarist wants to practice all the notes he can play, he should do it at home. There’s definitely a place for that type of playing, but it’s not in front of me.”

Angus would much rather listen to old-time players like Chuck Berry or B.B. King. “Those guys have great feel,” says Angus. “They hit the notes in the right spot and they know when not to play.

“Chuck Berry was never a caring person. He didn’t care whether he was playing his tune, out of tune, or someone else’s tune. Whenever he plays guitar, he has a big grin from ear to ear. Everyone always used to rave about Clapton when I was growing up, saying he was a guitar genius and stuff like that. Well, even on a bad night, Chuck Berry is a lot better than Clapton will ever be.

“Clapton just sticks licks together that he has taken from other people—like B.B. King and the other old blues players—and puts them together in some mish-mashed fashion. The only great album her ever made was the Blues Breaker album he did with John Mayall, and maybe a couple of good songs he did with Cream. The guy more or less built his reputation on that. I never saw what the big fuss was about Clapton to begin with.

“There are guys out there who can play real good without boring people. Jeff Beck is one of them. He’s more of a technical guy, but when he wants to rock and roll he sure knows how to do it with guts. I really like the early albums he did with Rod Stewart.”

If there’s one thing Angus really hates, it’s when people call AC/DC a heavy metal band. “It’s a cheap tag,” he says, “and it’s been stamped on us mainly from a media point of view. It’s an insult to be slapped in with hundreds of other bands. We look at it this way: we’re a rock and roll band. We don’t mind being called that—at least you’ve got a bit of individuality. Calling AC/DC heavy metal is like saying the Police is a reggae band, even though they may have a bit of that style. We’re just as individual. I mean, we don’t sound like Scorpions.

“Although we don’t consider ourselves heavy metal, I’m sure a lot of kids will jump out and say, ‘Yeah, AC/DC is heavy metal. They’re so heavy they can sink through the floor.’ But that comes from youth more than anything—the kids want to be a part of something.”

The kids who attend AC/DC concerts are, for the most part, teenage males—fans who would rather get drunk and rowdy than just rock out and enjoy the show. “We’re not a pop band,” explains Angus, “so there’s usually more guys than girls who come to our shows. Girls are more into the pretty side of things, like the Duran Durans of the world. We don’t go onstage with fancy haircuts and flashy clothes; we just go onstage and rock and roll.”

Born in Scotland, in 1959, Angus and his family emigrated to Australia in ’64. “There was a lot of unemployment in Scotland at the time,” remembers Angus, the youngest of seven brothers, “so my father took everyone to Sydney in search of work. He managed to find a job as a laborer.”

Although Angus had been messing around on a banjo in Scotland since he was five years old, it wasn’t until his early teens that he began playing guitar. “A kid down the road had an electric guitar,” he explains, “and I just picked up the thing and was able to play it. I don’ t know why and I don’t know how.”

Does Angus think he would be a better player nowadays had he taken lessons when he was younger? “Nah,” he says. “A lot of guitarists tend to throw their technique on you, which is a lot of crap, really. I’ve always thought that if you can clap your hands and stamp your feet in time, anyone can play guitar. I don’t think one needs to take lessons to learn how to play the thing. You give someone a chance to develop their own technique. If someone tells you how to play something, it could easily mess up your talent and corrupt your life. Everything you play should be done how you feel like doing it—very naturally. Playing guitar is like doing anything else—you’ve got to be able to think for yourself.”

Angus left school when he was fifteen. “Malcolm was putting together a band at the time,” recalls Angus, “and I joined. After a few rehearsals, I was really impressed. Malcolm said to me: ‘We’re just gonna have a good time and play what we want to play—very tough rock and roll, no pretty stuff.

“At first it was hard to find guys who thought like us. One guy we auditioned was a singer, but we told him, ‘We don’t want a singer, we want a screamer. You’re not the guy for us.’ But after a while we found some people and put together a good band.”

Two things happened: AC/DC was formed, and Angus’ short-pants routine came into existence. “It was my sister who suggested I play in the band with my school shorts on,” he explains. “After school I would go straight to rehearsals. I didn’t have time to go home and change if I wanted to get some solid playing in. Once day my sister told me, ‘Hey, it would be a great idea if you played in the band with your school outfit on—no one has ever done it before.’ It was such a great idea, I decided to do it. I was always one for something a bit original and different.”

To this day, Angus continues to play in shorts every show. However, a lot of AC/DC fans say it’s a worn-out routine. “I guess it depends on which fans you talk to,” counters Angus. “To me, it’s comfortable. If I took the stage and dressed like any other guitar player, I don’t think I would be able to be myself. The shorts are as much a part of me as my guitar.

“When I first started playing in shorts, it was a challenge. People would say, ‘Hey, this guy’s a clown—here comes Peepo or something.’ As a result, it made me work harder to prove to the people that I really did know how to play guitar. I just plugged it into the amp and played. I never used any of those ‘wangy’ bars or stuff like that.”

In fact, Angus hates tremolo units. “Those things never appealed to me,” he says. “If I want to get a similar kind of sound, I just de-tune the strings. Cliff Richards used to have this guy in his backing band, Hank Marvin, who used that thing on almost every note. He was like a Buddy Holly clone—he used to do these silly little steps. Guys like Hank set the music world back 20 years. I couldn’t believe guitarists like Beck looked at him as inspiration. Whenever I saw guys like Hank Marvin, I would always go in the complete reverse of what they were doing. Consequently, whenever I hear a tremolo, I can only think of him.”

Angus says his biggest musical inspiration was his brother George Young, who together with Harry Vanda produced the first few AC/DC albums. Vanda and Young, you may recall, were the guitarists in the Easybeats, one of the most successful Australian pop bands of the late Sixties. “We learned a lot from George,” says Angus. “He was the first one who said to us, ‘To be different, you must do everything your own way.’ When he first heard us, he was impressed with the fact that we could take someone’s song—an old standard like ‘Lucille’ or something—and make it sound like a new song altogether. George just let us do what we wanted. He didn’t make us put nice melodies in. If anything, he made us toughen our music up.

“Although George had more experience as a guitarist and a songwriter, he was also a good producer. A lot of people call themselves producers, but in fact they may be more of an engineer, since they know more about sound than about songs or arranging. 52 guitar legends ing. George knew about everything. A lot of producers can’t even tell you if your guitar is out of tune.

“George was great to work with in the studio,” adds Angus. “He always said that since we’re a rock and roll band, the less gimmickry, the better. The last album he did with us was our live album back in ’78, If You Want Blood You’ve Got It. I remember George saying ‘This is the last AC/DC album I’m gonna produce, since you guys already know enough about the type of sound and songs you want.’ ”

After considering a few producers (whom Angus says he would rather not name) AC/ DC settled for Robert John “Mutt” Lange, who produced the band’s next three albums— Highway to Hell, Back in Black and For Those About to Rock We Salute You. Of these, Back in Black was the most successful, becoming one of the best-selling albums of all time. “That album is our biggest selling album in America,” acknowledges Angus, “but our European fans preferred our early albums. A lot of the sounds on Back in Black are very much like the sounds you hear on the radio these days.”

Could this be why AC/DC decided to produce their last two albums themselves? “Not really,” says Angus. “We went from working with Mutt to producing ourselves simply because we wanted to. All the material was ready before we went into the studio on the three albums we did with Mutt. He left the music to us because he knew what we wanted. But the difference between us and any other band he’s worked with is that he likes to spend a lot of time in the studio—we don’t. I mean, he’s a good producer and he’s good at getting a great performance out of a band, but he spends too much time recording. We can’t stay in the studio for six months to a year working on an album—that’s ridiculous.”

Is Angus happy with how Fly on the Wall turned out? “We think we’ve done a good job and we achieved what we wanted. We just wanted to make a tough and exciting rock and roll record. And that’s what we made.”