“I hadn’t played bass to any great degree before I tried out for Oasis. When I was invited to come out and got on the plane, I didn’t have a bass”: Andy Bell looks back on crafting Ride’s mind-expanding shoegaze sound and playing in Britpop’s biggest band

The ‘90s were good to Bell. With Ride, there were the classic albums Nowhere and Going Black Again. Then there was Oasis. He looks back on a decade that changed everything – and the advice Blur’s Graham Coxon gave him about string bending

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

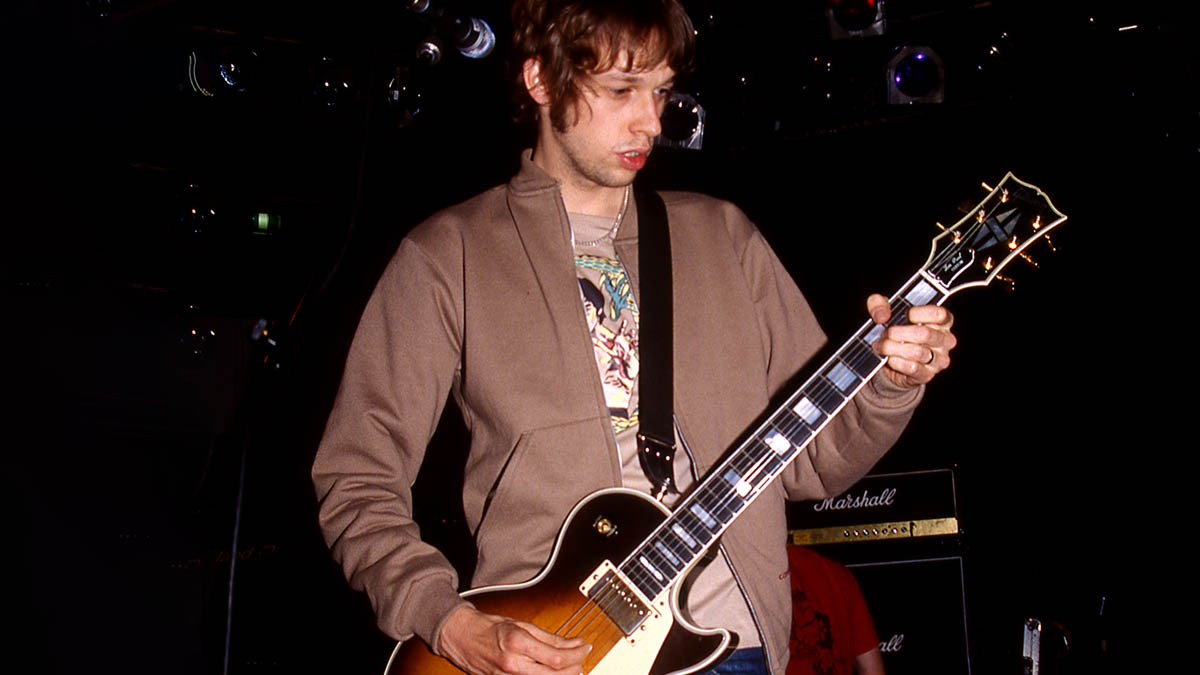

Before Andy Bell strode across grand stages with the U.K.’s most cocksure band, Oasis, he handled six-string duties for Ride, one of the shoegaze genre’s preeminent acts. Bands like Lush and Slowdive linchpinned shoegaze on the other side of the pond, but Ride’s first two records, Nowhere (1990) and Going Blank Again (1992), proved to be high points of the period.

Looking back on those records, Bell tells Guitar World, “I think there’s one moment that I remember that came after we finished Going Blank Again. When we finished that album, and it was mastered, [Ride guitarist] Mark [Gardener] and I drove back to Oxford, and he put it on his stereo at home. When we sat there and listened to Going Blank Again, we didn’t speak; we just listened.

“At the end, we were just like, ‘That is so good.’ But I don’t have a similar memory with Nowhere because, at the end, it was so stressful because we were hammering up against a deadline. The last days of Nowhere’s recording were chaotic; we worked night and day to mix it.

“But the guy who was supposed to mix it had a breakdown, which led us to call [producer] Alan [Moulder] to save the day. I don’t really remember having that same pleasurable playback moment with Nowhere where I said, ‘Ah, that’s a great record.’ I remember it being stressful.”

Stressful as it was, Ride’s greatness was painfully obvious, making it even more shocking that they didn’t last long. The group’s third record, Carnival of Light (1994), was a departure. And their fourth album, Tarantula (1996) – the final nail in the coffin before Ride’s breakup – while reminiscent of their earlier efforts, wasn’t enough to save the band in the face of dodgy relations and the looming shadow of Britpop.

Thinking back on Tarantula, Bell says, “I don’t think the songs on that album have the same feeling as the first two. But I’ll say this: Tarantula was an attempt to bring back the vibe of the earlier records. We started the Tarantula sessions soon after the Carnival of Light sessions because we were searching to get our vibe back. We could feel it slipping away; it was a last-ditch attempt to try and cook something up.

“A lot of those songs were not quite as ready as they should have been, but we wanted to try and capture a moment of spontaneity. But unfortunately, we didn’t. And I suppose those sorts of ideas can work, but they didn’t this time. And it wasn’t enough to save the band because it had already gotten away from us.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Not long after Ride’s demise, Bell formed Hurricane #1, which he recalls as “The first time I was in a band that had very defined roles,” before revealing that “it was like a rebound,” where the objective was “to do the opposite”. And while Hurricane #1’s two albums – Hurricane #1 (1997) and Only the Strongest Will Survive (1998) – were memorable, when the call came to join his old friends Noel and Liam Gallagher in Oasis, Bell didn’t hesitate.

“It was interesting,” he says. “Because when Guigsy [bassist Paul McGuigan] and Bonehead [guitarist Paul Arthurs] left Oasis, it’s not like it was something I was privy to. There were no prior discussions leading up to that point. I had been reading about it in the music press like everybody else. So when the offer came about, it came completely out of the blue.”

After a quick audition and reorientation from guitar to bass, Bell was off and running with Oasis. Thankfully, though, his first shows as part of the band’s new lineup – now with Gem Archer on guitar – were smaller, allowing Bell to break in gently.

“I seem to recall [my first gig with Oasis] was in the States, although I don’t know exactly where,” he says. “We did a short tour at the end of ’99, where there were maybe four or five shows. It was a sort of radio-promoted tour or something to that effect. It was Oasis, Blink-182 and a few other bands. I can’t remember much more than that. But I know it was quick, and we only played maybe five songs in the set.”

For the next 10 years, Bell, along with the rest of the members of Oasis outside of Noel and Liam Gallagher, weathered critical, commercial and interpersonal storms. And while it wasn’t always easy, unlike most before him, Bell managed to earn the respect of his bandmates and became a steady contributor across Oasis’ final three studio records.

Of course, Oasis have been gone for nearly 15 years, while Ride are back together and stronger than ever. Beyond that, Bell has his solo work and his latest project, Mantra of the Cosmos.

“I don’t feel pressure to amalgamate my history into what I’m doing now,” Bell says. “We make tracks and look to find freedom in the music. And we also think people should be able to dance to it. Being creative and moving forward is essential to me. The alternative, I guess, is making music that’s not meaningful, which is not an option.”

He concludes, “But I don’t have anything against nostalgia, to be honest. When the time is right, I love the opportunity to celebrate an old album. Ride recently played Nowhere in full, and we did Going Blank Again, too. But I guess I’ve always had a forward-moving approach in life that always has me embracing the chance to play. Life is too short, and outside of family, the greatest satisfaction I get is doing different things, finding different lineups and getting out there with my friends again.”

Considering the success of Ride’s reunion – and Bell’s willingness to bridge gaps via song – one can’t help but wonder if he’d be up for hitting the stage with Oasis should their long-awaited reunion come to pass.

“Oh, absolutely,” Bell enthuses. “If that happens, I’m there for it, mate.”

As soon as I started playing Vapour Trail, I said, ‘Guys, listen to this. This is really good.’ And my next thought was, ‘How the fuck am I gonna remember it?’

After the release of 1990’s Nowhere, the media labeled Ride “the brightest hope for 1991”. Did that sort of pressure register at all?

“My reaction was, ‘Yeah, you’re fucking damn right we are.’ [Laughs] But we were full of confidence by the end of 1990. We’d only been going for around a year by that point and had really put the right foot forward with the three EPs we did, and then Nowhere.

“The songs we were writing were great, and we’d just been on an American tour, so we were cooking with gas. So we finished 1990 on a high note, and I remember seeing a lot of positive press about us, which fueled us going into the second album, Going Black Again.”

People often attribute Ride’s songs to Mark Gardener, but you wrote a ton, one being Vapour Trail, which, for my money, might be the best song on Nowhere. How did you put that together?

“Vapour Trail was one of those songs that came together very fast. The guitar line stands out; I remember exactly how it was written. We were on tour in the U.K., playing in small venues and staying in bed-and-breakfast hotels with a series of beds in the same room.

“All four of us were sleeping in dormitory-style rooms, and after the gigs, we’d sit around with a couple of guitars, having a smoke or drink. I remember sitting there with a guitar while hunched over the bedside, and that’s when I came up with the four chords that make up Vapour Trail.”

Did you immediately know you were onto something?

“As soon as I started playing it, I said, ‘Guys, listen to this. This is really good.’ And my next thought was, ‘How the fuck am I gonna remember it?’ Because we didn’t have any way of recording it while sitting in this room as we were. I just went to bed thinking, ‘I’ve got to remember this riff, and if I can remember it in the morning, then it’ll be cemented in my head.’ And luckily, in the morning, I grabbed my guitar and picked up where I left off the night before. I was like, ‘Right, cool, that’s locked in now; it’s recorded in my brain.’”

Did the lyrics come just as quickly?

“The phrase Vapour Trail and the lyrics that follow came from a friend of mine who ended up moving into my house in Oxford. He was dating this girl and had written a card to her and was trying to think what to write in it, and he wrote this message to his girlfriend, ‘Your vapour trail in a blue sky…’ and I thought, ‘That’s cool. I’m having that. I’m gonna put that into a song.’”

Going Blank Again features heavy doses of distortion, wah and feedback. How did that progression take place? Was it natural, or did you seek to apply that approach?

“Personally, the progression from Nowhere to Going Blank Again was pronounced because I had bought a 12-string Rickenbacker in between the two albums. And I had become friends with Graham Coxon of Blur, who I’d see often as they’d just become popular.

“I loved Graham’s fluid, bendy guitar style. That sort of elastic guitar playing appealed to me, and I remember saying to him, ‘How are you getting that sound?’ And Graham said, ‘It’s really simple; it’s just a Les Paul,’ and then he said, ‘See, you’re playing a 12-string Rickenbacker; the strings are not going to bend. You’ll kill your fingers trying to bend on that guitar.’”

So the Les Paul was the key to your sound on Going Blank Again?

“Yes! Graham telling me that was what made me get my first Les Paul. And when I did, I took it to the studio and started talking to Alan Moulder about the string-bending thing I wanted to do. That’s when Alan showed me the classic, cliché Jimi Hendrix string bend where you bend the third string up, which matches the second string’s note [commonly referred to as a unison bend – Ed]. You know what I mean? He showed me that, and then, if you listened to Leave Them All Behind, you can hear that I immediately adopted it and played my own version of what Graham was doing in Blur.”

By the time Carnival of Light came out, Britpop was in full swing. How did the success of bands like Oasis and Blur affect what Ride were doing?

“I can only talk about my own experiences at the time, but I think it did. We started on Carnival of Light not too long after Going Blank Again, and it definitely was more of a retro-sounding record.

A lot of people were listening to ’60s music around that time, and you can hear that with us; bands like Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd and other late-Sixties and early Seventies prog rock bands

“A lot of people were listening to ’60s music around that time, and you can hear that with us; bands like Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd and other late-’60s and early-’70s prog rock bands were being embraced. Whereas with Oasis and Blur, they went down a route that was more like the Kinks.

“I know a lot of people linked them to the Beatles, but when I first heard Oasis, I didn’t think of the Beatles. I heard the Kinks and the Sex Pistols way more than I heard the Beatles in the earlier stuff.”

You became friendly with Noel and Liam Gallagher somewhere between Carnival of Light and Tarantula, right?

“Yeah, well, it was just before Carnival of Light. I remember going to see Oasis at a Creation Records showcase that Alan [McGee] took us to, and that’s when I was introduced to Liam. I told him, ‘You guys are amazing; we’ll have to get you out on tour with us,’ which was me naively thinking that Oasis would be supporting Ride on the Carnival of Light tour. Little did I know that Oasis’ first single would come out a few months later, and they’d be bigger than Ride overnight. They just exploded.”

We had made two great albums, but we were starting to flounder because of the direction we were going in with Carnival of Light... We were cleaning up our sound when other bands were getting dirtier

The overnight success of Oasis, Blur and other Britpop bands undoubtedly changed the state of music in the U.K. How did that affect Ride’s fortunes?

“We had our own stuff going on as well. We had made two great albums, but we were starting to flounder because of the direction we were going in with Carnival of Light. Looking back, that direction didn’t particularly suit Ride very well. We were cleaning up our sound when other bands were getting dirtier.

“There’s a real dirtiness to Oasis’ first album, Definitely Maybe, which was punky and aggressive. That sound was a lot like the early Ride sound, but we’d moved away from that and became cleaner and more polished.

“It felt like by the time Carnival of Light came out, what we had moved toward was sort of irrelevant. But there was also stuff happening where things weren’t working well anymore. It wasn’t long before we broke up, maybe a year or so later.”

When you joined Oasis in 1999, what was the directive?

“I hadn’t played bass to any great degree before I tried out for Oasis. So when I was invited to come out, when I got on the plane, I didn’t have a bass. So I couldn’t even try to learn anything before I got there. But I knew the chords to the songs, and I did my best to play the root notes; but I have to say, I probably wasn’t that good on the first run-through.

“The other thing was that I was playing bass with my fingers, and Noel said, ‘Guigsy played with a pick. Try it that way.’ And when I did, I found I could attack the bass in a way that sounded a lot more like Oasis.”

I hadn’t played bass to any great degree before I tried out for Oasis. So when I was invited to come out, when I got on the plane, I didn’t have a bass

How steep was the learning curve from there?

“I did enough in the audition to get me into the band, and then I went away and learned the catalog. I literally spent hours every day over the Christmas holiday learning all the tracks inside out so that I could nail it.

“And that was a massive education for me; being in that band, in general, was such a learning experience. To get inside a new instrument and feel the way drummers and bass players work together through that dynamic within a band was brilliant.”

Was being in a band with Noel and Liam Gallagher as tumultuous as it’s been made out to be?

“I would have to say yes. [Laughs] I’ve been in many bands over the years, but that was my first brush with true greatness on a worldwide scale. And that’s not meant to put Ride down because I love Ride. That’s what I identify with most because they’re my school friends.

“But in terms of global superstars of music, being in Oasis was just so huge. To be in a band with those guys was a huge learning experience. And their charisma – it’s a real thing. It was another level. And later, one of my proudest moments was that Oasis would start its set with a song I wrote called Turn Up the Sun. That was just unbelievably cool.”

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.