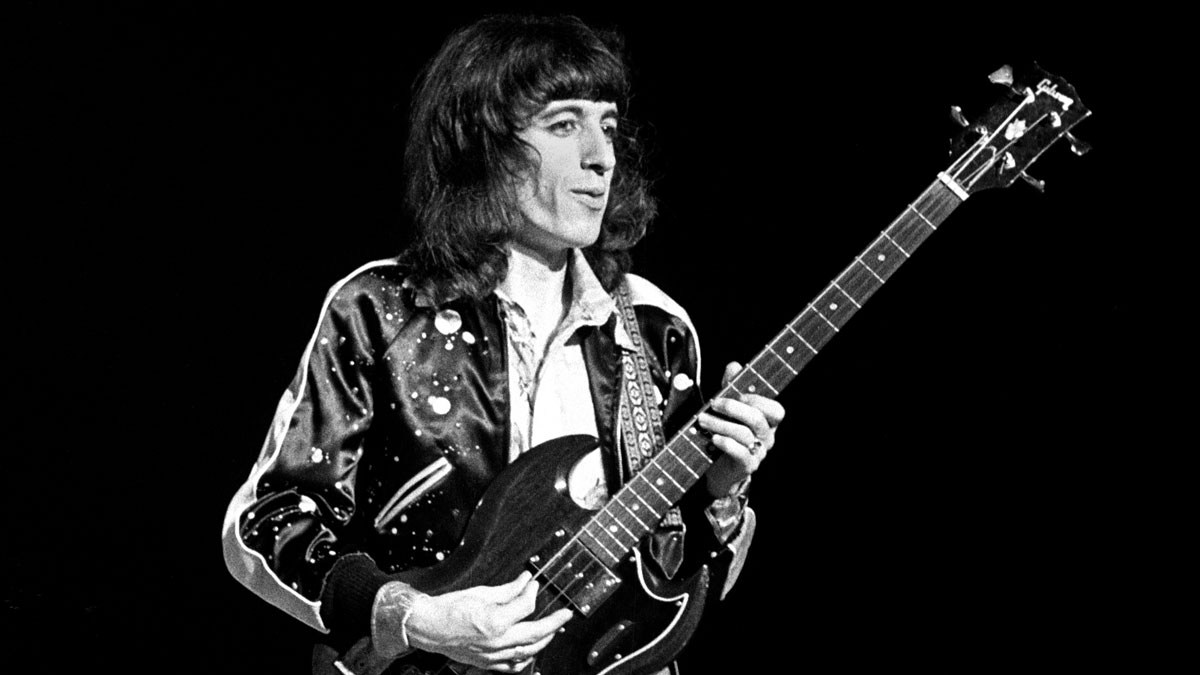

Bill Wyman on making The Rolling Stones' Exile On Main St.

"I used to get fairly disappointed when you couldn’t bloody well hear my bass"

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“That the album ever came out at all was a complete miracle,” marvels Bill Wyman of the 1972 landmark Rolling Stones album Exile On Main St.

Though critics initially overlooked the band’s provocative blend of American roots music with Brit-style rock (“Everybody slagged it off,” Wyman bitterly recalls), the album has since gained recognition as one of the Stones’ most potent statements. This year, Universal has re-mastered the seminal double album, reissuing it with a blistering batch of bonus tracks.

As Wyman intimates, making the album wasn’t easy. The band had fled England to escape the nation’s harsh tax laws (93 percent at the time), and its members were in deep financial trouble.

As the album’s title suggests, the boys felt exiled from their homeland, and slithered off to the friendlier confines of southern France. It was there that they recorded the bulk of Exile in the sweltering basement of Keith Richards’s rented Côte d’Azur mansion in Villefranchesur- Mer, a previous Gestapo headquarters from World War II.

With the assistance of producer Jimmy Miller and 21-year old engineer Andy Johns (whose resume already included three Led Zeppelin albums), the Stones created 18 tracks that perfectly assimilated their fascination with older American music styles—blues, rock, gospel and country—into what has since been hailed as the Rolling Stones ultimate masterpiece.

While previous complaints about the original release stemmed largely from its awful sound quality and abysmal mix (rushed by Johns at Jagger’s insistence), the new release overseen by producer Don Was puts a new sheen on things, while retaining the spirit and grit of the original.

Soul survivor

Born William George Perks in the Lewiston Kent section of London on October 26th, 1936, Bill Wyman had been a Rolling Stone for nearly a decade at the time of Exile’s initial release. Initially inspired by the acoustic walking-bass style of blues legend Willie Dixon, Wyman found equal merits in Donald “Duck” Dunn’s straightforward, uncluttered electric style with Booker T and The MGs. Prior to joining the Stones on December 7th, 1962, he had already designed his own fretless electric bass guitar. At 26, married with a child, Wyman was seven years older than the still teenaged Jagger and Richards, whose more bohemian tastes ran quite differently.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Recalls Wyman, “When I first joined the band, they asked me what kind of music I liked, and who my favorite artists were. When I kind of mentioned certain favorites of mine, they kind of went, “Ugh,” You know, it’s weird looking back now, but they originally hated bluesmen like John Lee Hooker and Lightnin’ Hopkins. They preferred the electric blues of Chicago. They also hated Eddie Cochran, but in the ’80s and ’90s I got them to doing ‘Twenty Flight Rock’ onstage. It was the same with Jerry Lee Lewis. They hated him when I first joined, but later Keith became a mad fan.”

Throughout his thirty year tenure with the Stones, Wyman teamed with drummer Charlie Watts to form one of rock’s most solid rhythm sections, driving such Stones classics as “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” “19th Nervous Breakdown,” “Honky Tonk Woman,” “Brown Sugar,” “Start Me Up,”and “Miss You.” Additionally, Wyman maintains he created the iconic riff used for “Jumpin Jack Flash,” although Richards ended up playing it on the record.

In 1974, Wyman became the first Stone to release a solo album, Monkey Grip. He also became the first one to score a hit single, when “(Si Si) Je Suies Un Rock Star,” became a surprise European hit seven years later. In December of 1992, exactly thirty years after joining, he surprised the music work by announcing his departure just when the Stones were about to sign a huge contract with Virgin Records. The band was undisputedly the world’s richest touring attraction.

Although Wyman claims otherwise, it’s clear that the split was less than amicable. It was generally assumed that when Wyman, 56 at the time of his leaving, and just about to get remarried and begin a new family, wanted to forsake the hectic world of performing, in favor of the serenity accorded to a retired country millionaire gentleman. Yet 18 years later—the eclectic musician turns 75 next year—Wyman maintains a vigorous touring schedule with his band, the Rhythm Kings. True to his earliest musical inspirations, Wyman maintains the same enthusiasm for the roots American music that first caused him to pick up a guitar as a young kid.

Were you asked to do any new overdubs on the newly remastered Exile, as Keith, Mick Jagger, and Mick Taylor did?

No, and neither was Charlie—we didn’t have to. [Co-producer] Don Was was full of compliments about our playing in an article I recently read, which was very nice.

One of the problems on the original album was that your bass was buried in the mix.

Well, they’d always sink me way deep. There would always be separate mixes, and then they’d argue about which ones to use. I didn’t get involved, but yeah, I used to get fairly disappointed when you couldn’t bloody well hear my bass. But they wanted more of Keith’s guitar, or whatever. I suppose I just lived with it.

I also didn’t always get the proper credits I deserved, either. When you read the back of the Exile album, it says someone else is playing bass on songs when it was actually me. Mick would always get the credits wrong, and it was too late to change them. So that was annoying, as well.

Were the recording sessions as chaotic as the legends about them are?

In the studio, we just worked weekdays, and we broke on Saturdays and Sundays. So, on the weekends, if Keith was alive, he would mess about with the guys that were staying in the area, like [saxophonist] Bobby Keyes, [trumpet player] Jimmy Price, and [producer] Jimmy Miller. [Engineer] Andy Johns was living there, so if they felt like going in to record, they could.

Keith went in one weekend and did “Happy” with Jimmy playing drums, and it turned out quite nice, actually. It was quite a pleasant surprise coming in on Monday morning, and hearing it being played back. [Note: Miller had previously played drums on “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” and did the famous cowbell intro on “Honky Tonk Women.”]

What was the studio setup like?

The sessions there were a complete nightmare. The situation where we were recording was a joke, being down in some sort of cellar. Condensation poured down the walls, so you had to be stripped to the waist. The horns were in the kitchen up the corridor. There was no cameras or mics; no direct contact with the mobile studio outside. You had to go up the stairs to talk to anyone. My bass was under the stairs outside one bloody room or another.

In what ways did the primitive recording conditions affect you?

The unfortunate thing was that if I wasn’t there when something was being recorded somebody else played on the original track. So either Keith would lay down a bass with Charlie, or else Mick Taylor would.

Of course, when I came back and the bass was already there, what was the point in me overdubbing if it worked well? If Keith or Mick or Mick Taylor weren’t there for something, they were always able to overdub their instruments later. That was the inconvenience of being part of the band’s rhythm section. If Charlie wasn’t there and Jimmy played drums, then Charlie could never be on that track, like the other guys could.

What was a typical recording session like?

It was really stupid, but even more stupid was that nobody ever turned up the same time. On a Monday, Mick Taylor, Charlie, and I might arrive. Keith would be upstairs sleeping, never appearing at the session. We’d all traveled from God knows where. Charlie was five hours away from where he stayed at my house. Piano player Nicky Hopkins often stayed by me, and when you’d get there, you’d find out that Mick Jagger had gone off partying with some local celebrities.

So, we’d just mess about, and then the next time, Mick Taylor wouldn’t be there. It would just be me, Keith and Charlie, and Mick Jagger wouldn’t turn up again, because he’d gone to Paris or someplace to buy rings for his wedding [to Bianca Perez Morena de Macias]. Then the day after that, Mick would turn up with Charlie and me, but Keith wouldn’t be there, and neither would Mick Taylor. It was like that day after day. It was bollocks—it’s a miracle that record ever came out, because it was all done in bits. The whole band was hardly ever there at the same time. It was really madness.

Being that Keith’s heroin consumption was quite heavy at the time, how on top of things was he?

I shouldn’t be talking about this, but a typical example of things was that you’d break for the weekend. You’d finish the session at like ten in the morning, drive all the way back through the crowds, going to the beaches, get home about midday, have some lunch, go to bed, and then on Sunday there’s be a phone call saying, “Um, some people broke into Keith’s house when everyone was watching television and stole all the guitars and a saxophone. People just came in and cleaned out all the instruments. [Note: Reportedly, drug dealers to whom Keith owed money were responsible for the heist.]

Absurd things like that were going on, and it was just a complete joke. But being that is was Keith’s house, he was quite happy to work at any odd hours he cared to. We were all obliged to being there when it suited him more than anybody else.

You’ve stated in the past that one reason you stayed away from many of the Exile sessions—including those for “Tumbling Dice” and “Happy”—was the drug use, which you didn’t want to be around.

I suppose. There were problems there that stayed with us right straight through the ’70s, and as I was not the least interested in taking drugs, but suffered the same consequences as the others—airport checks, etc.—and I wasn’t very happy about it. Everybody else got into problems. It was a real nightmare.

During your time with the band, beside not being formally credited with coming up with perhaps the best Stones riff ever, for “Jumping Jack Flash,” there must have been many other instances where you weren’t officially credited, as a co-songwriter.

There were lots, because all of the songs were created in the studio. You know, Keith would come in with a riff. That’s all, and over the course of a week we would come up with a song. Then Mick would write the lyrics, and it would come out on an album credited as “Jagger-Richards.” That would happen all the time.

I did get a bit disheartened that they weren’t generous enough to share, like many other bands do. Like the way the Beatles gave room for Ringo Starr and George Harrison to do their thing, and how the Who gave John Entwhistle a chance to write stuff. Where other bands shared things, the Stones didn’t. We just had to live with it or leave. So I went on and did solo albums and movie music, and I produced other artists. I got satisfaction in that way.

What do see as some of your most unheralded contributions to their music?

I loved recording “Paint It, Black,” when I laid on the floor and pumped the organ pedal with my fist, because I can’t play with my feet. That rhythm kind of made the record, because it was lacking something before I suggested doing that. I suppose you could also say I created what was happening on “Miss You,” you know, the walking bass, that octave bass thing. After that, just about every band in the world took that idea at the time and used it in a song. Rod Stewart used it, and a lot of funky bands did, also.

What was your most memorable moment with the Stones?

The best one for me was the Hyde Park concert in 1969, on the 5th of July, two days after Brian Jones died. I loved playing live— that was kind of magical.

Which was the band’s best tour?

They were all great. They all kept getting better. I mean, the ’69 tour was fantastic until Altamont. [Note: that concert was marred by a fan fatality.] We had a fantastic tour with Chuck Berry, Terry Reid, Ikeand Tina Turner, and B.B. King—I loved that tour. Japan in 1990 was also fantastic, when we did ten shows in a row, between 45,000 and 52,000 for each show. No one ever did something like that.

Did you feel when you left the band two years later; that its best music was in the past?

I think the best music was done between ’68 and ’72. Never mind about when I left in ’92.

When was the last time you saw the Stones in concert?

It was at London’s O2 Arena in 2007 or 2008. I don’t hear the Stones the same way now as when I was in the band, because in those days, it was all sort of dangerous and loose. Now, it’s like a machine. It’s like they’re playing to click tracks, which we never did. The music has become more machine-like than I would like, and that’s not the way it was when I was with them.

Considering even just all of the millions you could have earned with them over the past 18 years, do you have any regrets over leaving “The World’s Greatest Rock and Roll Band?”

Are you serious? [Laughs.] Not one iota—I never have. I enjoyed my time there, and I’m still mates with everyone. Except for Charlie, they didn’t understand my leaving at the beginning. So there were bad vibes and nasty comments going out in the press. But then they were all right with my decision. I got married, and they understood what was happening with me. We still send each other birthday and Christmas presents. We’re still family, but I don’t want to see them every day of the week—once in a while is okay.

Will we ever see Bill Wyman grace the stage with The Rolling Stones again?

If they did one big final live performance that was broadcast all over the world—and they asked me to do it—I probably would do it for the fans. But at the moment, it doesn’t interest me. I’ve had my time.

Flashback

Here’s what was on Wyman’s mind when Bass Player last caught up with him in 1998....

On His Novel Approach With The Stones

I was one of the first bass players in England to understand I had to play along with the bass drum. Jazz musicians and Americans were doing it, but we didn’t think like that in England. Luckily the band learned all these little tricks very early.

On His Rock & Roll Peers

I heard these incredible, magical bass players—Jack Bruce, John Entwistle, John Paul Jones, and Felix Pappalardi. I totally admired their technique, but I couldn’t stand the way they played; they were all too busy. It’s like another guitar—there’s nothing underneath. Ronnie Wood plays like that, too. He’d play on a Stones song if I wasn’t in the studio, and he’d always ask me later, “What do you think of that, Bill?” I’d always say, “Bloody horrible! Where’s the bass?” [Laughs.]

On The Stones’ Musicality

We were all quite naïve—everything we did came from inside. We felt it.

On Slow Grooves

I always enjoyed playing the slower songs; I was often able to be a bit more melodic.

On “Paint It Black” Needing Two Coats

When we were finished, the boys thought the bass needed to be a bit more ballsy. I suggested organ pedals, but then realized I didn’t know how to play them! So I laid on the floor and punched the pedals with my fists.

On Tracking Tricky Arco Bass

On “Ruby Tuesday,” my stretch was a problem. I knew where the notes were, but I wasn’t able to get it together. I finally said, “Maybe someone else can bow while I finger the notes.” Keith said he would, so we ran through it once to show him what to play. It worked perfectly.

On His First Electric Beast Of Burden

I was playing in an R&B band in 1961 when I bought it. Until then I’d been playing on a detuned guitar, so I was glad to finally have a "real" bass. Unfortunately it was bloody horrible!

On Giving His Bulky Bass A Shave

I’d seen Gibson and Fender basses in pictures, so I drew a shape like that on the back of the bass and had my neighbor saw it down. I beveled the edges, took off the paint, and put in a Baldwin pickup. But it rattled with every note because the frets were so worn. I pulled out the frets—figuring I’d replace them when I could afford it—and when I did, the bass suddenly sounded good. I used it on every Stones album up to 1975. Even without an amp, it sounds wonderful— it’s got the sound.

On Touring With Framus Star Basses

They were the only basses with necks as narrows as my fretless. And the boys liked the sound of them onstage; they cut through, but were still boomy. I moved on to use a smaller Framus, shaped like a Les Paul bass and with a wood-grain finish.

On His 1965 “Signature” Vox Bass

They never approached me beforehand. They just appeared with this awful, spoonshaped thing and said, “We want to call it the Bill Wyman Bass—we’ll give you 5%.” I never saw any money from them, and I never liked their bass.

On Keith’s Fender Benders

Keith loved James Jamerson, and he’d always be saying, “You should play a Fender—they get such a good sound in the studio.” But they’re simply too big for me. I tried a couple Jazz Basses, but I ended up giving them away. When I heard about the short-scale Mustang, I thought I’d finally be able to manage a Fender—and please Keith at the same time! [Laughs.] It wasn’t too bad. I used it onstage a bit, but it never felt quite right.

On His Stubby Steinberger L-2

No one in the band liked the looks of it, but the sound was really good. The problem was that with no headstock, I had nowhere to put my cigarette! We ended up gluing a pen cap to the end of the neck—it was a perfect fit!