“I get fingers pointed at me. I get told, ‘You’re the guy who tried to kill Randy Rhoads.’ I laugh it off. He needed to be with better people. How could our split ever be friendly?” Kelly Garni founded Quiet Riot – but it ended with shots fired

They went to school together, started Quiet Riot together and then had a drunken fight involving a gun that ended Garni’s musical career. 25 years later, he came back to the bass

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

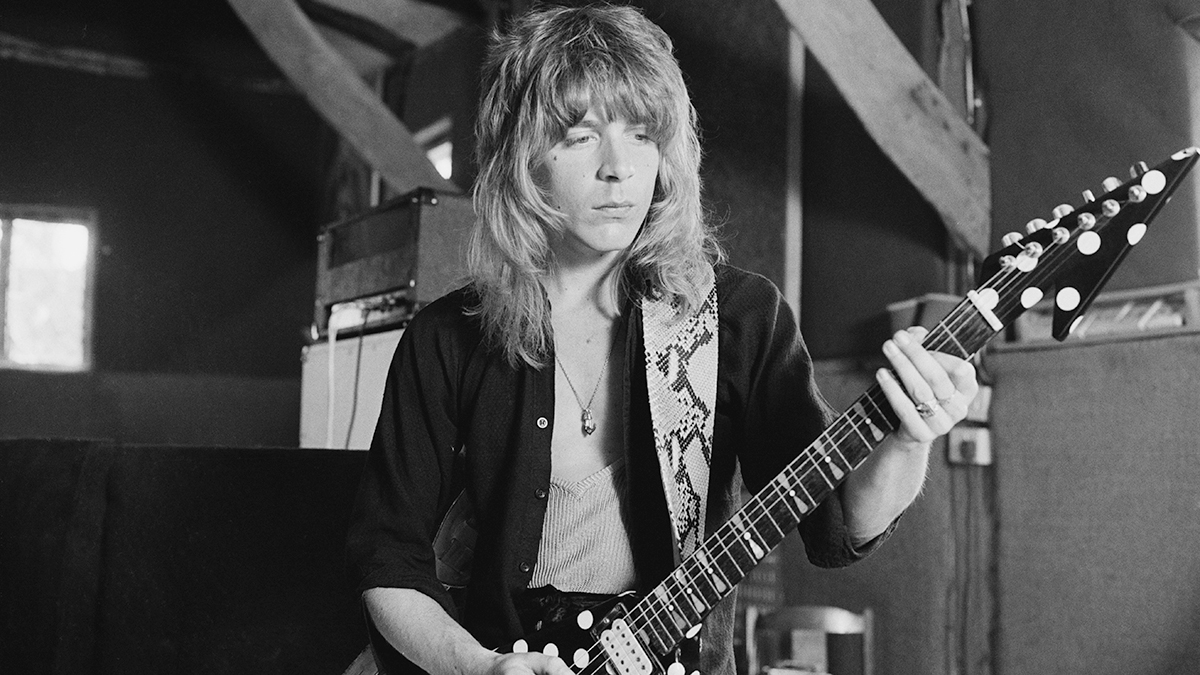

Kelly Garni grew up with Randy Rhoads and formed Quiet Riot with him in 1975. The bassist was fired three years later after a drunken brawl with the guitarist – whose promising career ended in a plane crash seven years later.

“I was inconsolable,” Garni tells Bass Player. “I couldn’t even go to the funeral. I just didn’t want to see that reality.”

He’d already given up playing and begun a new life as a paramedic. It took him years to get back to bass.

“I started playing again in my early 50s; I’m 68 now,” he says. “I got a call from Todd Kerns, who wanted me to come play with his band.

“I said, ‘I don’t own a bass – I haven’t played in 25 years. I don’t think I can do it.’ Todd convinced me, and I’ve been doing it ever since. I’m getting offers to play in bands, and I could; but I don’t want to.”

He continues: “People still have a lot of respect for Randy. They have high regard for what we did, so I play those old songs. I’m the last man standing; Drew Forsyth [drummer] is still alive, but he wants nothing to do with it. So I’m all you got.”

How did you and Randy meet?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“He was a guy I noticed in high school who seemed very interesting. We were both in a new school, sort of outcasts, so we gravitated together. I went to his house and he told me he played guitar.

“He didn’t know how to play lead, but I thought he was pretty good. He was taking lessons from Scott Shelly at his mother’s music school. From there, it turned into him needing a bass player, so he turned me into a bass player!”

Did Randy teach you how to play bass?

“He began to teach me basslines. As he was learning his leads, he’d practice over my basslines. I’d play for four or five hours straight, and he’d just do the same things over and over until he had them perfected.

“From there we got good enough to where we could establish little bands that played at backyard keggers. When I was about 15 we formed Quiet Riot. We found Kevin DuBrow and Drew Forsyth, who we’d used in previous bands.”

What was your and Randy’s vision for Quiet Riot?

“We just kind of made it up as we went along. We tried to stick with trends that were popular. This was 1976, so Randy and I were heavily influenced by Alice Cooper, David Bowie and Black Oak Arkansas – the first concert we went to together.

“Kevin was heavily influenced by British music, like Slade and flashier bands. That clashed a bit with what me and Randy wanted, but we made it work. That’s the reason our first two albums have sort of a poppy sound: there was a lot of Kevin's involvement there.”

Is it true that management steered you in a lighter direction?

“The management wanted us to be the next Bay City Rollers, and we didn’t. When the time came to write songs, they were telling us, ‘It needs to be more pop.’ Randy and I thought it was horrible – but Kevin was all in.

“At that point he’d kind of taken over the band. I didn’t feel that Randy and I were playing in a style we wanted, but Kevin insisted that if we wanted to make it, it’s what we had to do. So we went along with it.”

People looked at Randy’s equipment and said, ‘How did he get that sound out of that?’ But it literally came out of his fingers

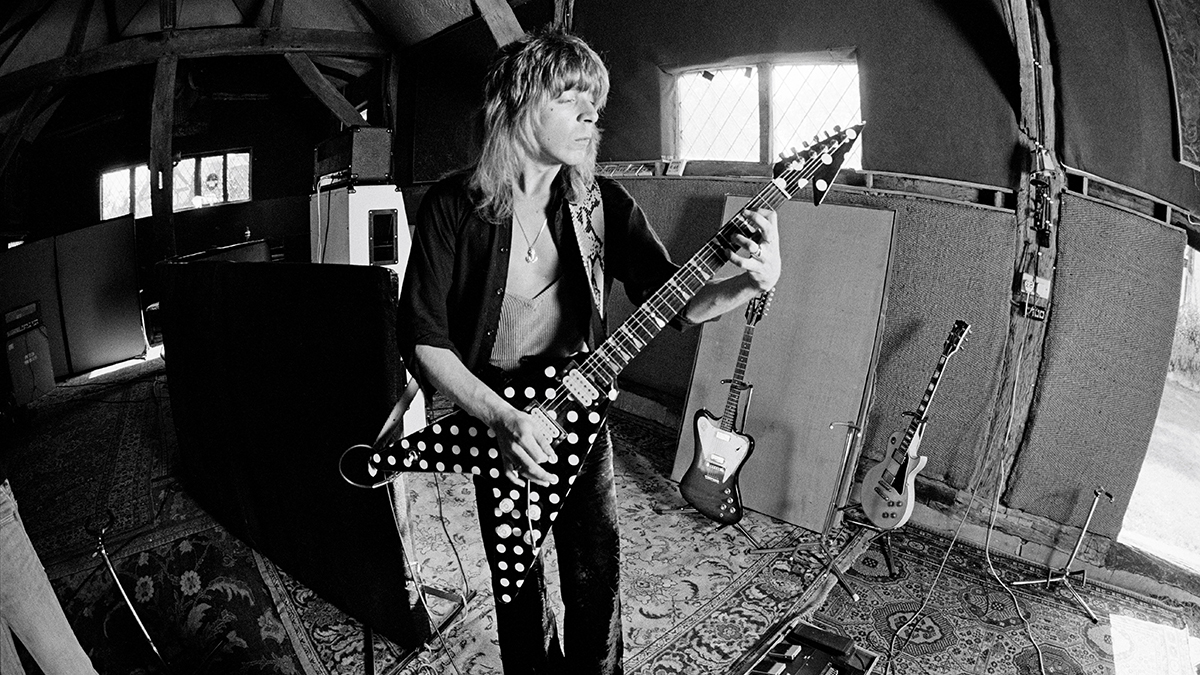

When did Randy’s beloved cream-colored Les Paul come into the picture?

“He got that guitar from our first manager, who we both adored. He didn’t have any experience and only a little bit of money, but he put a lot into the band. To me and Randy, he was a great friend.

“Randy had talked about the guitar, and the manager had an extra cabinet lying around, so he traded it and got that guitar. Many people think Randy paid him back, but we didn’t have that kind of money. I never saw Randy give him any money, and I would have, because we were always around each other.”

Were you able to afford decent amps?

“Randy had a Peavey Standard head, which I thought sounded great for bass. But he made it sound great for guitar, and he had an Ampeg 4x12 cabinet that was oversized. I was using two Acoustic 370s.

“Most people looked at Randy’s equipment and said, ‘How did he get that sound out of that?’ But it didn’t come out of the amps – it literally came out of his fingers. It’s a strange thing; the tone was in his fingertips.”

Even though it was early on, could you tell that Randy was a great player?

“There was no doubt about it. He wasn’t a guy who got better every six months, or every month, or every week; he got better every 60 seconds. Literally, he’d play one thing, and 60 seconds later he would play it amazingly. And 60 seconds after that, he’d play it like only he could.”

You and Kevin weren’t getting along by the time the second record came, leading to a drunken fistfight between you and Randy involving a gun.

“Yeah. I was unhappy for quite a while. The band as we were had stalled; we weren’t going anywhere and weren’t doing anything. It seemed like rinse and repeat; there was no progress. We weren’t making any money and management gave us an allowance, which in my case was $40 a week to live on.

“It was frustrating. I was getting older – I was 20, and we still hadn’t gotten anywhere. We seemed to have some success in Japan, and the management kept saying we’d go there, but we never did. This all came to a very drunken conclusion. The night before it happened I’d gone to a club called the Cabaret, and it caught on fire.

“Everyone ran out of the building, leaving me sitting there with these two girls. It was starting to look like, ‘Well, maybe we should leave, too,” but I was having a beer and a cigarette and I didn’t want to leave yet. I thought, ‘So what if there’s a fire?’ That’s the stupidity of youth; the invincibility of youth!

Randy volunteered to leave with me. I said, ‘No, you stay. I’ll do something else. You believe it, so you continue’

“On the way out the door we saw the bar had been abandoned, so I hopped over and started handing these girls bottles of booze. I grabbed a whole bunch of bottles, and the girls were stuffing bottles into their bras, down their pants and into their purses!

“As we walked out there was a big crowd, and a fire truck pulled up and blocked the view of us. So we went to my car, opened the trunk and put it all in there. I had about 25 bottles of liquor. The next day I called up Randy and said, ‘Hey, the Cabaret caught fire and I robbed the bar. I got all this booze over here. Come over and party!’

“After four or five hours of drinking, we started discussing the Kevin problem. It got out of hand. I told Randy to leave; he refused. And I lived in the Barrio in Van Nuys, a pretty dangerous place, so I kept a gun hidden in the couch.

“I pulled the gun and fired it into the ceiling, thinking that would make Randy leave. But he was fearless – he didn’t leave, he charged right at me. The gun was automatic, so it reloaded and cocked itself. I chucked it aside to get it out of the mix, and the fight was on.”

Had you and Randy gotten into fights before?

“It certainly wasn’t the first time we’d been in a fist fight. We grew just like brothers, had squabbles and rolled on the ground; and that’s basically what this amounted to, though it was a bit more serious. It was also terrible how drunk we were, particularly me, and I wasn’t done.”

Is that when you hatched the plan to find, and possibly kill, Kevin?

“I was going to finish this job; I thought I’d kill Kevin. I don’t think I actually would have – that’s just not in me. But I certainly would have scared him, and I probably would’ve gotten the cops called on me.

“When I got in my car and tried to drive, I could not. I had to go around the block to re-park the car, and I blew a turn right in front of an LAPD cop. They pulled me over in front of my house; I had a gun in a shoulder holster under my jacket, and off to jail I went.

“Once Kevin and management heard about the episode, they said, ‘Okay, that’s it. He’s got to go – he’s too big of a problem.’ That was it.”

How did Randy feel about that?

“I spoke to Randy the next day, after I got out of jail. We were laughing about the whole thing. Any fights we had, we always quickly made up and they became funny. Most people don’t think this sounds funny, but we did, because nobody really got hurt.

“Well, there was some blood – Randy raked his famous long fingernail across my forehead and opened it up pretty good. But nobody was hospitalized or anything.”

Was Randy okay with you being ousted?

“He volunteered to go with me. I said, ‘No, you stay. I’ll go. I’ll be fine; I’ll do something else. You believe it, so you continue.’ We were still friends. But he was in the band and I was not. I did a total 180, cut off all my hair, enrolled in paramedic school, and had a job waiting for me when I graduated. I worked and ran calls in the back of an ambulance for the next 10 years in LA.”

Do you have any regrets about how things ended?

“I don’t. I thought about this a while back; I was always trying to think of the perfect way to say what I meant, and I finally came up with the feelings that seemed to justify everything that happened. I don’t have any regrets because Randy needed to be with better musicians than me and the other guys in Quiet Riot.”

Like the guys he ended up with in Ozzy’s band.

“No matter how you slice it, at some point, me and Randy – still as best friends – were going to have to part ways. If I’d stayed in music it would have been a lot harder. It was never, ever gonna be pretty. But at least we laughed about it, though nobody else did!”

It took about three seconds for me and Kevin to start hugging each other and crying

You’ve taken a lot of heat from people who have a different perspective.

“I get fingers pointed at me. I get my story convoluted. I get told, ‘You’re the guy who tried to kill Randy Rhoads.’ I laugh it off and say, ‘You weren’t there; you don’t know.’ Randy needed to be with better people. After nine years of playing together, how could it ever be a friendly thing?”

Did you ever make amends with Kevin DuBrow?

“That did happen. A mutual friend of ours came to me and said, ‘You and Kevin have too much history together. It’s a shame you aren’t friends. You need to get in a room together and work it out.’ And that’s basically what we did.

“It took about three seconds for me and him to start hugging each other and crying. Not long after that, he moved to Las Vegas, and we were great friends. He was always there for me and I was always there for him. And, of course, we talked about Randy a lot.”

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.