Glenn Hughes: "It’s been rumored that I’m the only pick bass player who sounds like he’s playing with his fingers"

The Voice of Rock talks Black Country Communion, Black Sabbath and his love of Bill Nash basses in this classic interview from 2011

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Glenn Hughes has done 10 times more of everything than you, including playing bass. From his early band Trapeze, via three years on top of the world in Deep Purple, to an ill-fated stint in Black Sabbath and now a triumphant return to the top of the rock world with Black Country Communion, Hughes and his bass have been places most of us would never dare dream of.

A full-fat rock band like they used to make in the 1970s, BCC features Hughes on bass and vocals alongside blues prodigy Joe Bonamassa, drummer Jason ‘Son of John’ Bonham and keyboard player Derek Sherinian.

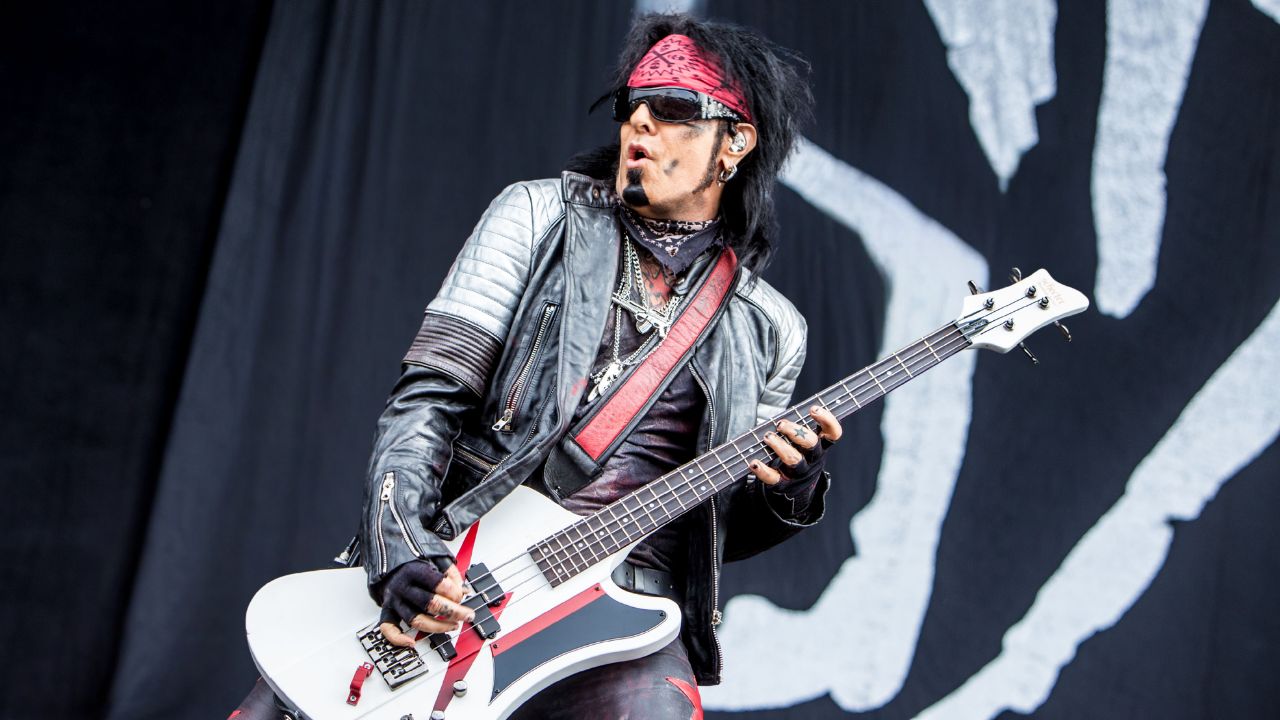

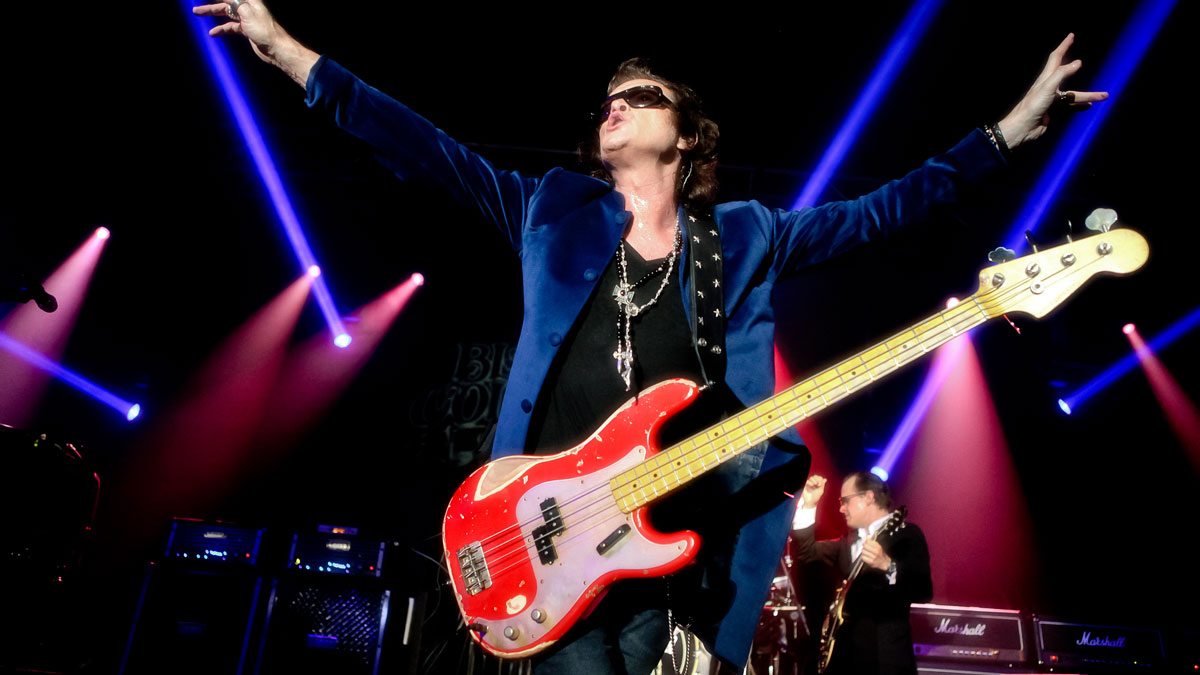

Amid the heavyweight sounds of his bandmates, Glenn’s bass parts punch through with great clarity and power – and you can attribute a lot of this to the rather splendid new Bill Nash gear he’s using.

“I’ve known Bill since 1981 when I was making the Hughes/Thrall album,” he tells us. “I bought a G&L bass from him when he was working at a guitar store in Reseda, California, but I hadn’t been in touch with him for years.

“Then I was over in Australia three years ago and I went into a record store: there were all these old guitars on the wall – Precisions, Telecasters and Stratocasters – and I started to play them and I thought ‘These are incredible.’ They weren’t Fenders, though: there was nothing on the headstock to say who they were made by. I found out that they were Bill Nash guitars and basses, and I was completely floored.”

The first Black Country Communion album, a self-titled record released in 2010, featured a lighter, tauter, more top-heavy bass tone, but for the follow-up, titled 2, the band and producer Kevin Shirley opted to go heavier and more classic.

As Glenn explains, “I used Bill Nash’s 1957 P-Bass on the new album, because we went for a different bass sound – an ambient sound which will be really huge live. Kevin and I decided that we’d use a rounder tone – more of a late-60s sound than a 70s one – which makes the track sound bigger.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“The album is generally heavier than the first one: we talked about how people might have done this in the '60s and '70s to get a big sound. There’s more low end and less top. Compare it to the song ‘Black Country’ from the first BCC album: that song has the Glenn Hughes tone of yore – the sound that people have always associated with me.”

Nash’s gear was chosen for this return to a classic sound, Glenn says, simply because of the undeniable quality of his instruments: “I usually like to go with the originals when it comes to the old Fenders and Gibsons, but I was so impressed by how brilliant these guitars sounded. Bill’s guitars have that vintage tone: I have no idea how he does it.

“So I’ve got a red Precision, which I played with Black Country Communion at Shepherd’s Bush last Christmas, and a creamy-white one. They have the signature Glenn Hughes sound that I had in Deep Purple and Trapeze: the sound that I really always wanted to go back to.”

He adds: “I’ve had all the five-string, six-string and eight-string basses; I’ve been the active bass thing; I’ve done all that. Now I’ve gone back to the passive four-strings. I have a lot of Fenders, but these Bill Nash basses are insanely good.”

Glenn began his career on the cabaret scene in Cannock, Staffordshire in the mid-1960s – as a guitarist. How did he switch to bass?

He recounts: “My friend Mel Galley [late, great guitarist who later played in Whitesnake] was in a band called Finders Keepers. I had taken his place as guitar player in 1968. The bass player in the band had had enough of the music industry and quit to get a day job. He mentioned to the leader of Finders Keepers that he knew this kid in Cannock who might switch from guitar to bass – and I took up the bass solely so I could be in a band with Mel, who I idolized. He’d already been an amazing guitar player even when I was only 12 or 13. I would have gone anywhere to play with him.”

“The first bass I picked up was a 1962 Jazz,” he continues. “It was a salmon color. Finders Keepers’ old bass player sold it to me. It was a great bass. I remember the first song I played on it was ‘Fire Brigade’ by The Move, because we were a covers band like most groups were back in the 60s.

“I noticed that a lot of guitar players were switching to bass at that point, and they were playing with a pick in a different style. I took me about a year to find the groove and the sensitivity to be a decent bass player. I play fingerstyle too, but I play about 90 percent of the time with a pick.

“It’s been rumored – and I’ve heard this from a lot of people – that I’m the only pick bass player who sounds like he’s playing with his fingers. I think pickless, if that makes any sense.”

By the time Finders Keepers morphed into the much funkier – and much more successful – Trapeze, Glenn had evolved a bass style that was indebted to Motown, R&B and soul.

“By the first Trapeze album in 1969, I think I was up to speed,” he recalls. “I practiced avidly and I still do today, because I love playing – whether alone up in my studio, or with other people. I like to find melodic notes and putting them into really cool parts in the songs. I think it’s harder to play guitar and sing at the same time than it is to do the same thing with bass: for me, playing bass and singing just comes really naturally to me.”

Asked where trademark fills such as a fast vibrato on the 14th and 15th frets on the E string come from, he remarks: “That’s from my early influences: black R&B. It really comes from a lot of black bass players – Verdine White, for example.

“I know him, they opened for Purple: it was about that time, in the early 70s, that I started to use this technique, and nobody was really doing it in rock music. I’m not finger-popping as such there, but I do use a wide vibrato.”

Although the groove is the most important element of Glenn’s playing, he doesn’t do the old slap and pop very often, if at all.

“I use it sparingly. I think it’s been overdone,” he explains. “I do some cool runs, but it’s the notes that I don’t play that are the most important. Leaving a lot of space is really important for me. There are a couple of songs on my solo albums that have a slap line, but really I’m not a finger and thumb player most of the time, and I’ve stayed away from it because a lot of people do it so well. Even bass players that aren’t brilliant can still slap. Drummers can actually pick up a bass and slap! It’s a bit of a trick.”

Check out any pictures of the very early Mark 3 Deep Purple line-up – Glenn plus David Coverdale (vocals), Ritchie Blackmore (guitar), Jon Lord (organ) and Ian Paice (drums) – and you’ll notice that his bass of choice was initially a Rickenbacker 4001. This didn’t last long, he explains.

“I was in Trapeze in early 1973 and I was being courted by Deep Purple, and I knew that they were going to ask me to join. I was in Houston, Texas and I swapped a then-new Fender Jazz for a new Rickenbacker 4001. It wasn’t great for Trapeze because it’s not a funk instrument, but I thought that it might work for Purple and I took it down to Clearwell Castle to record the first Mark 3 album, Burn, and on that first tour.

“It worked well on Burn, but when we got into the live situation and the band started to stretch itself out and jam, I needed to go back to the Fenders. That’s when I bought the 1963 P-Bass which you can see me playing at the Cal-Jam.”

The California Jam, perhaps the closest the 1970s ever came to a Woodstock, was an enormous 1974 festival that saw over 400,000 people watch Purple, ELP and Black Sabbath among many other bands of the day.

Soloing with a Cry Baby wah and strutting the stage in a white satin suit, Glenn was iconic – but what happened to those equally iconic Rickenbacker and Precision basses over the years?

“The Precision got stolen,” he replies. “I was moving to California in 1979 and I had to go through Denver to see my then-wife’s family. My bass and guitar never came up on the luggage carousel.

“About four years later, I got a call from somebody in Texas asking me if I wanted to buy them back, so it had obviously been set up. A lot of instruments had been lost at Denver airport, and mine was just one of them. I freaked out: I wasn’t cool and collected enough on the phone to figure out how to talk to this guy. I was so furious with him, and that was the last thing I heard about that bass. He didn’t even discuss how much he wanted…

“As for the Ricky, in 1976 I was rehearsing in Birmingham, doing my first solo album Play Me Out, and I ran into Geezer Butler of Black Sabbath, and I sold him that Rickenbacker. He’s still got it. We had a new Year’s Eve party recently and I asked him if I could buy it back, and he said ‘I don’t sell me basses!’”

After Deep Purple split in 1976, riven by drug abuse and exhaustion, Glenn recorded his solo album and drifted from project to project, battling cocaine addiction. Somehow he never lost his world-class voice, leading to an unlikely appointment in 1985 as the singer of Black Sabbath.

“That gig came at the wrong time for me,” he explains now. “In order to front a band like that you need to be on form. It would have been much easier just to play bass. I can sing without an instrument now, but back then it was just weird.”

Although this part of Glenn’s career wasn’t without its rewards – an album with Pat Thrall, for one – he didn’t fully rediscover his talent until the 1990s, when he kicked the drugs completely and returned to form.

Basses have come and gone since then, he says: “I had a signature Yamaha BB, with a reduced body size. That was in 2008; I was at the NAMM show with Marco Mendoza and Yamaha asked me to come over to the family. They made me a signature passive bass and it sounded wonderful: it’s on my First Underground Nuclear Kitchen album. It’s a great guitar and they’re a great company.”

As for the rest of his signal chain, he explains: “I don’t have any effects with Black Country Communion, but with my solo band, I’ve got a DigiTech Bass Synth wah which sounds like the left hand of a Moog organ, kind of like Stevie Winwood would play. I also use an Xotic Robotalk Auto Wah for that kind of envelope filter sound.”

After so many years at the low end, what wisdom does Glenn have to offer the world of bass?

“It’s really about finding melodic lines that don’t interfere with the vocals and the drums. Find the right family to play with. Listen to the drummer and find the groove: the groove is what defines my bass playing. There’s a lot of bassists out there who have everything but the groove – but it’s the key.”

Bass Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful bass publication for passionate bassists and active musicians of all ages. Whatever your ability, BP has the interviews, reviews and lessons that will make you a better bass player. We go behind the scenes with bass manufacturers, ask a stellar crew of bass players for their advice, and bring you insights into pretty much every style of bass playing that exists, from reggae to jazz to metal and beyond. The gear we review ranges from the affordable to the upmarket and we maximise the opportunity to evolve our playing with the best teachers on the planet.