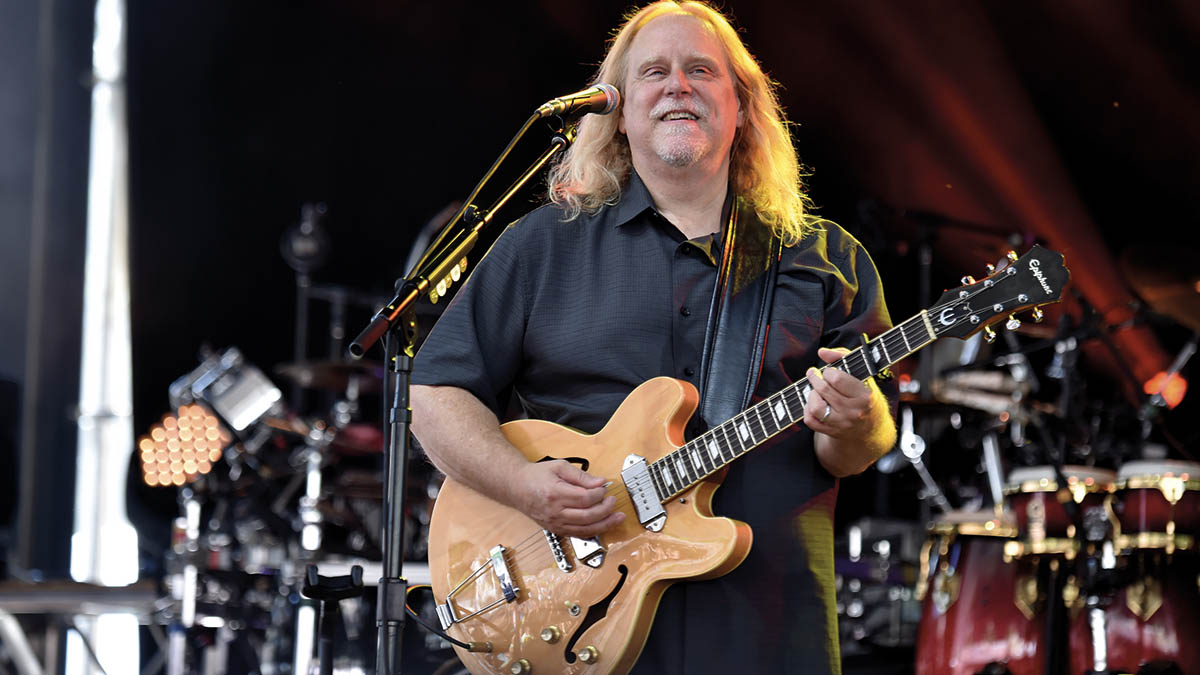

Warren Haynes: “I go into a project hoping to do no overdubs. It rarely works out like that, but I feel like all my best parts are when I’m playing live with the band”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

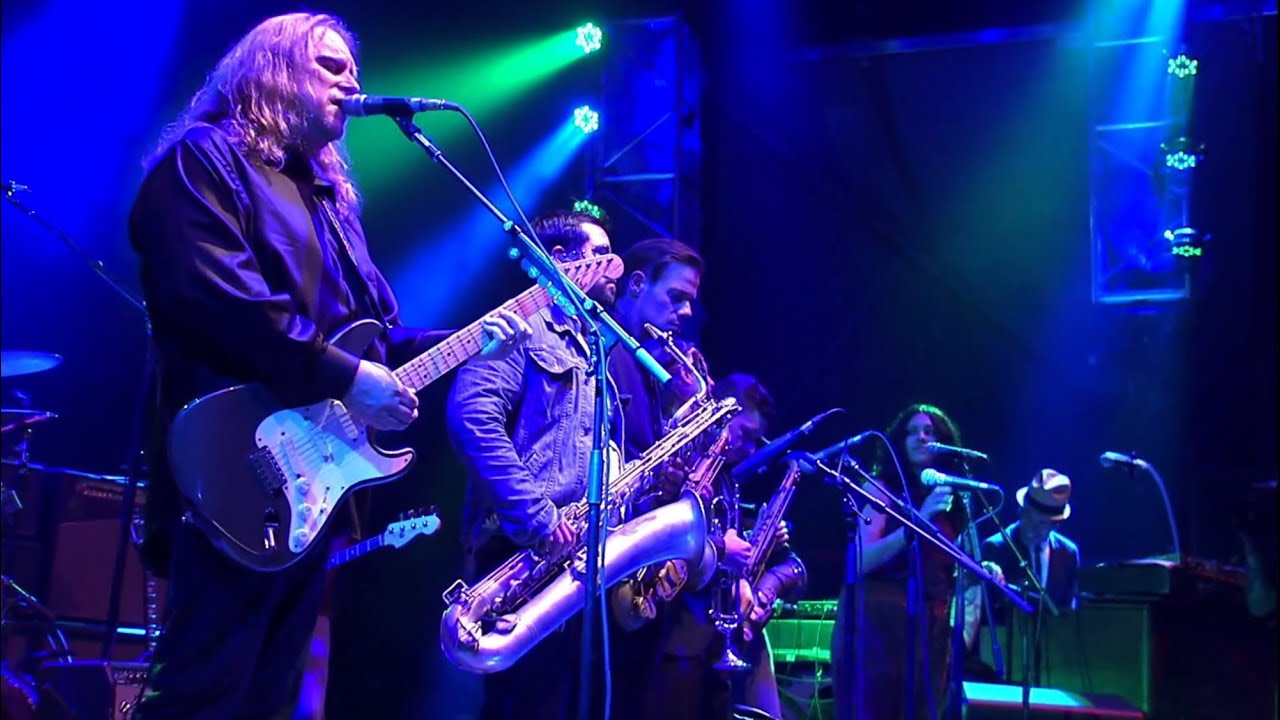

You could be excused for feeling surprised at the news that Gov’t Mule’s Heavy Load Blues is Warren Haynes’ first proper all-blues album. The music has been at the heart of Haynes’ playing – not only since Gov’t Mule’s 1995 self-titled debut, but since he burst onto the international scene with the Allman Brothers Band’s 1989 comeback album, Seven Turns, and established himself as one of the great guitar heroes of the last quarter-century.

But Heavy Load Blues is indeed the first time that Haynes has released a complete collection of blues songs, split evenly between originals and tunes by Elmore James, Howlin’ Wolf, Junior Wells and other blues luminaries.

“I’ve been thinking about doing an album like this for a very long time, but I was not sure if it would be a solo project or a Mule record,” Haynes says. “I’m a bit surprised, too, that it’s taken this long, but what better time than now after the pandemic?”

Gov’t Mule was started by Haynes, bassist Allen Woody and drummer Matt Abts as an outlet for Haynes and Woody to bust out of their day gigs in the Allman Brothers Band and stretch the boundaries of music. They were paying tribute to power trios like Cream, Mountain and the Jimi Hendrix Experience, with material often rooted in the blues but ready to blast off in any direction.

It’s the template the band has retained for 26 years, through Woody’s 2000 death and the transformation from trio to quartet with the addition of keyboardist/second guitarist Danny Louis. Jorgen Carlsson has been the band’s bassist since 2008.

Through all those changes and developments, the band’s essential approach has remained steady, as evidenced by the group’s previous studio album, 2017’s ambitious Revolution Come Revolution Go.

When Haynes’ wife and manager Stefani Scamardo suggested that the time was right to record the blues album they had long discussed, Haynes was excited but also hesitant for one simple reason: he had been extremely productive writing songs during the pandemic-induced time off the road.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Our mission became finding a place where we can set up two entirely different setups and record two records at the same time. And that’s what we did

“I was home more than I’ve been since I was 15 and consequently did more writing than I’ve done in decades,” he says. “There were a lot of negatives about that time, but that was one of the positives. So I thought that it would be a lot of fun but also that I’d written all this new music, and really wanted to record it as well.”

Haynes came up with an ambitious solution, the kind that comes naturally to him: recording two albums simultaneously.

“Our mission became finding a place where we can set up two entirely different setups and record two records at the same time,” Haynes says. “And that’s what we did.” The second album will be out in 2022.

You actually cut two albums at once, which is pretty amazing. Tell me about that process.

“The other album is what I consider the followup to Revolution Come Revolution Go – the next proper Mule album. We did not record back-to-back albums; we recorded both at the same time. We were set up in two different rooms.

“In the big room, we had all our Gov’t Mule toys. And there was a much smaller adjoining room, with low ceilings, with an entirely different setup: small drum kit, a bunch of little amplifiers, and no headphones. And we just played live like we were in a little club in there.

“We would go in early in the day and record new songs all day. Then somewhere around dinnertime, we would take a break and over the next couple hours, move over to the blues room and start playing blues for the late night. Same routine every day.”

Did you even have to think about whether the blues album should be cut late at night?

“No. It was kind of obvious. Johnny Winter said that Muddy Waters said that Hard Again was his favorite recording experience because Johnny let him record late at night. He said it’s not natural to play the blues in the middle of the day, and I tend to agree.

“Also, there was something really cool about the fact that we would go in and record these Gov’t Mule songs all day that were much more complex or structured, and then at the end of the day we could stop thinking and just play blues. It was like taking off ankle weights. We could step away and kind of get lost in the other world for a while.”

The album has a real vintage feel. Were you aiming to evoke a specific sound or era?

“It was important that the two records sound completely different from each other. We wanted Heavy Load Blues to sound [the way] those old records – cut between about 1955 and 1975 – sound in our heads. Since we were set up completely live, with even vocals going down on the track, everything’s bleeding into every microphone, with no way of separating one instrument from another.

“And we were literally right on top of each other, like being on a small stage, except facing each other. Matt had a really small drum kit, the organ was playing through an Ampeg B-15. I had all these old little amps set up and I could just plug into one or more; I often had one in the room with us and two out in the big room being mic’d far away.”

When you’re dealing with Elmore, it’s really about the lyric because the songs are so similar to each other

The first song, Blues Before Sunrise, is not the Albert King tune, but an obscure Elmore James song.

“That caught me off guard! I was looking for an Elmore song that I hadn’t done before. When you’re dealing with Elmore, it’s really about the lyric because the songs are so similar to each other, but this also had a strange feel in the way the vocal melody fits in with the chord progression. It sounds like it has an extra bar.”

And the sound is so authentic. What are you playing?

“A Danelectro Pro 1 through a Supro, and maybe one or two other amps. The vocal is coming through an amp as well. I had two vocals set up: a bullet mic going through a Fender Champ, and a regular microphone going through an amp that wasn’t quite as dirty. We could also blend the clean sound in or not. It was all about capturing an inspirational vibe.”

Love Is a Mean Old World and Hole in My Soul are both originals based around cool riffs. Did they start there, or did you add them at the end to complete the song?

“The horn riff that opens Hole in My Soul was something that was in my head, and I just sang it into my phone to capture it. The song was separate, and at some point I realized they go together. I wrote Love Is a Mean Old World with Ray Sisk and Rick Huckabee about two years ago, and it just has a vibe about it... it’s kind of traditional blues – and kind of not.”

It’s nice to hear you bring back If Heartaches Were Nickels, which you wrote a long time ago when you were making publishing tapes to sell to others, and

“Joe Bonamassa ended up recording it on an early album [2000’s A New Day Yesterday]. I wrote that in ’86 or ’87. I recorded some blues demos, which is where Tom Dowd heard it and played it for Joe Bonamassa. And then Joe wound up recording it. There was a demo of Before the Bullets Fly from that same session, and Gregg [Allman] ended up recording that.”

You’ve played Feel Like Breaking Up Somebody’s Home a lot, but this is your first recording of it.

“Yeah, that’s the only one that we wanted to include that we played live in the past, and mostly because we’ve kind of come up with our own arrangement that’s really cool. And we thought it would be good to at least give it a try and see what happens and if it turned out good, we would keep it, because we didn’t dwell on the blues stuff.

“I had a big list of songs, which I tried to prioritize, but it changed all the time. I was pleasantly surprised that it turned out to be half and half: seven covers and seven original songs.”

I love that you included Tom Waits’ Make It Rain.

“Me too. I just love it. It was always kind of a priority because I love that tune and thought it would stand out and occupy its own unique space on the record, which it does.

“We had this kind of wild thing happen with the reverb tank while recording it. I have two Fender spring reverb tanks; one’s old and one’s new. Billy Gibbons gave me the new one when we toured together because the old ones are so problematic.

When we were recording Make It Rain all of a sudden, we get these noises, which I think were radio frequencies, that would set off the reverb, and it literally sounded like rain

“I was having an issue with the old one when we were on tour, and he was like, ‘Oh man, they made a really great reissue of that’ and he ordered one for himself and one for me and they shipped them out on the road. We utilized both of them throughout the project.

“The old one was stable, but when we were recording Make It Rain all of a sudden, we get these noises, which I think were radio frequencies, that would set off the reverb, and it literally sounded like rain.

“One of the first times it happened was the first time I say ‘make it rain’ – all of a sudden it cackles like a rainstorm. We’re all looking at each other and laughing; during the keeper take, it happened over and over, to the extent that we didn’t think we were going to be able to use the recording. We listened back and it just sounded like we were playing in a rainstorm. I was glad that we kept going!”

Did you also record the other album all live?

“Mostly. The biggest difference aside from the size of the rooms – the blues room has a much lower ceiling, and we were much closer together – and the gear itself is that I was using a monitor for vocals and also running it through an amp, so no headphones on the blues album. None of us wore headphones, which we did on the other album, which meant separation – and keeping a small amp near me and another one in a different room.”

On a completely pragmatic level, what is the impact of wearing headphones?

“Whether you can overdub. If we were isolated and wearing headphones, if somebody played something they want to fix, they can. But on the blues stuff, you couldn’t punch it in because everything was in every mic. For example, because I was standing four feet from the drums, my voice was in all the drum mics. My voice is bleeding from the monitor into every track, so you either keep the track or redo it, but you’re not punching in a fix.”

Knowing you can’t fix something could make you more conservative. Is there any part of your brain that wants to go that way?

“No. I think it was more liberating than anything. It’s so much more fun to play without ’phones. It always takes me a couple of days to get used to wearing ’phones on any project, and I never like the way my guitar sounds in the headphones, so hearing it in the room like you’re used to hearing it live really is much more inspiring for me.”

If you don’t like the sound of your guitar in the headphones, then are you basically just relying on…

“Instinct. In the long run, if you’re not happy you can redo it, but in my recordings most of the solos are recorded live on the track. I go into a project hoping to do no overdubs. It rarely works out exactly like that, but I feel like all my best parts are when I’m playing live with the band.”

It’s interesting that the title track of the album is acoustic. What did you play on that?

“A Gibson L-1 ‘Robert Johnson guitar’. I think it’s 1929, and it’s not really loud – though it has a beautiful, authentic sound. Your instinct is to play it hard, but it doesn’t sound as good. That was the last thing we recorded, just me and Danny [Louis], who was playing a ’60s Gibson Hummingbird. I was playing and singing at the same time, so we were married to whatever happened.”

But you could always do another take! What’s the maximum number of takes you did on this?

“It was almost all three takes or less. None of it was laborious and a bunch of them were first takes, including Heavy Load. The vocal felt really good and natural and we did a couple more, but that was the best. I really liked the comfortability of the vocal, and since we’re keeping the live vocals, it’s just part of it.”

Elmore James probably didn’t have a choice but to do just a take or two, but you do. Is it hard to get yourself in that frame of mind?

“No. My experience has always been once you go past three takes, you’re trying to recreate what you’ve already done. If you don’t have it, it’s probably best to step away, take a break and come back to it. If we play a song at soundcheck and it sounds good, then we don’t play it that night because we feel like we just played it.

My experience has always been once you go past three takes, you’re trying to recreate what you’ve already done

“The blues record was kind of that way; let’s make sure and capture the early takes because they just wind up being better. And going back to what you said about the Elmore recordings, all those records had mistakes on them – or what somebody would consider a mistake. But if you removed those mistakes, would it be better or would it be worse?

“Howlin’ Wolf’s original I Asked Her for Water is such a strange recording. It’s got that weird atonal riff going on and it takes a minute or so before the band can agree on what the riff actually is. They’re all playing it differently, and for some people that might be off-putting, but I find it beautiful and perfect.”

Tell me about the National steel you played on Black Horizon.

“I just got that from Derek [Trucks]. I called him because I was looking to buy an old National and I thought he might know of one for sale. He has an incredible one that was owned by Bukka White [acoustic blues great and B.B. King’s cousin and inspiration].

“And he said, ‘I’ve got two 1939’s that are kind of sister instruments. It would be cool if we both had one, so why don’t I just sell you mine?’ I was so moved by him parting with it, and it’s become a real prized possession. We’re looking forward to getting these two guitars back together! Every time we play together is a beautiful experience.”

What other guitars did you play on this album?

“It was almost a different guitar for every song. I think I played 12 guitars on 14 tracks. They’re all mine, except I borrowed Allen Woody’s three-pickup SG Custom, which is late ’60s or early ’70s and is exactly like the one I had when I was a kid, to play on Snatch It Back and Hold It. And I borrowed a 1963 ES-345 from my friend Paul Zagler for Hole in My Soul.

“Wake Up Dead is a Custom Shop SG. Love Is a Mean Old World is a Plummer electric resonator guitar in open G. Ain’t No Love in the Heart of the City is my Tobacco Sunburst Les Paul that was my Allman Brothers guitar. It was a factory second from Gibson. It was hanging on the wall because they couldn’t sell it because it had two extra screw holes that somebody put in the wrong place.

Make It Rain is a ’50s or ’60s Danelectro parts guitar that almost looks like a non-reverse Firebird with lipstick pickups and a flame back. It’s a very strange one

“I went to Gibson and played every tobacco sunburst guitar they had but none of them were speaking to me, and Rick Gembar said, ‘What about that one hanging on my wall that we can’t sell?’ It was just wood: no tuners, pickups, knobs, anything. They said, ‘Give us about 15 minutes and we’ll put it together.’ And it felt great!

“If Heartaches Were Nickels was my ’61 ES-335. Make It Rain is a ’50s or ’60s Danelectro parts guitar that almost looks like a non-reverse Firebird with lipstick pickups and a flame back. It’s a very strange one.

“Blues Before Sunrise is my other Danelectro, a ’60 Pro One. Asked Her for Water and Feel Like Breaking Up Somebody’s Home are both my ’59 Les Paul. (Brother Bill) Last Clean Shirt was the ’61 ES-335. The Savoy Brown tune, Street Corner Talking, is the Flying V that Grace Potter gave me. And You Know My Love is a sunburst Epiphone Riviera.”

What guitar amps did you run them all through?

“Mostly cool little vintage amps, including a tweed Gibson Vanguard, which is a ’59 or ’60; a tweed Gibson Skylark, which is the same vintage; an old Supro; a tweed Fender Pro and a little Alessandro recording amp that I use quite a bit. And then on a couple of things I used a ’90s Gibson Goldtone, which is really cool. That’s what I used with Dave Matthews at Central Park.”

- Heavy Load Blues is out now via Fantasy.

Alan Paul is the author of four books, including Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band and the Inside Story of the Album That Defined '70s as well as Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band – both of which were both New York Times bestsellers – and Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, a memoir about raising a family in Beijing and forming a Chinese blues band that toured the nation. He’s been associated with Guitar World for 30 years, serving as managing editor from 1991 to 1996. He plays in two bands: Big in China and Friends of the Brothers (with Guitar World’s Andy Aledort).