Interview: ZZ Top's Billy Gibbons and the Black Keys' Dan Auerbach

Mississippi Fred McDowell’s haunted, woody voice sails through the air as the Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach nurses a cup of coffee and flips through a vintage lunchbox-sized valise designed for carrying 45 rpm records.

“Lord, when you get home baby,” the late bluesman cries as his slide guitar cuts a zigzagging melody, “won’t you write me a few of your lines.”

“Found it!” Auerbach exults as McDowell keeps spinning on the well-used turntable at his Nashville home base, Easy Eye Studio. He pulls an orange-labeled single out of the case and shows it to Billy Gibbons, who’s sitting next to Auerbach on the worn office sofa, sipping a Diet Coke.

“The first ZZ Top record, on Scat. I want to have you sign it,” he says.

“Sure,” Gibbons says, examining the flashback from his—and the music industry’s—past.

“Cool,” Auerbach replies. “Which was the A-side: ‘Miller’s Farm’ or ‘Salt Lick’?”

“It was ‘Salt Lick,’ ” Gibbons says in his laconic twang.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

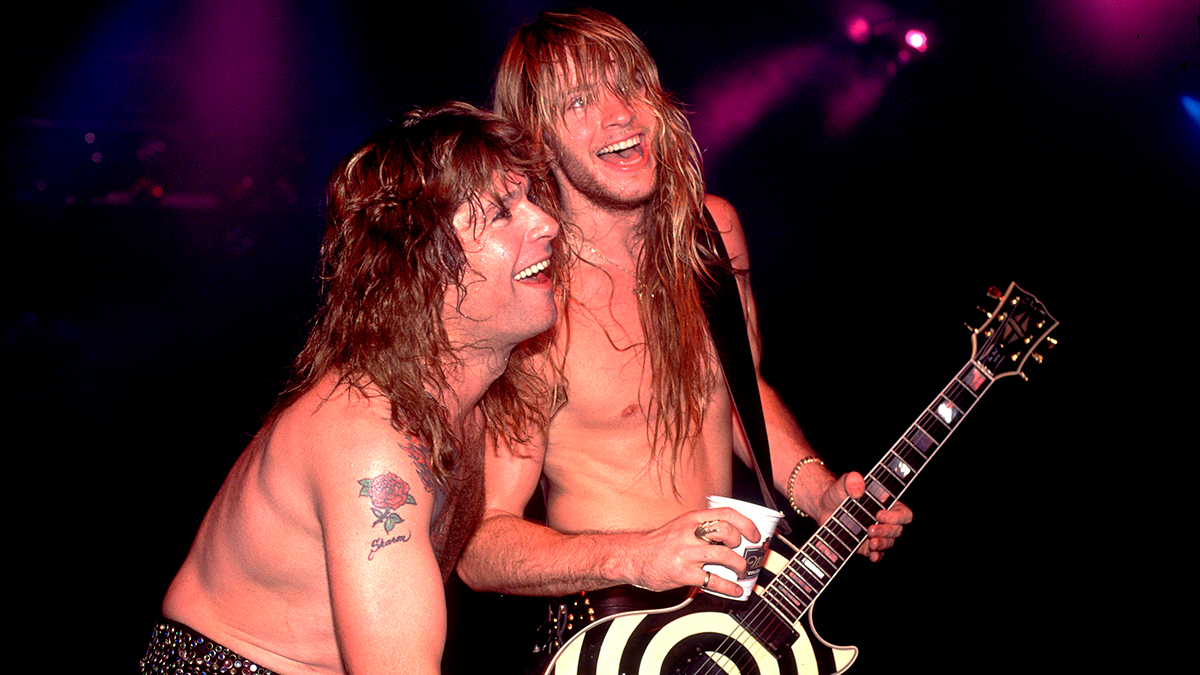

It’s a classic moment: Gibbons, the godfather of Texas-style blues rock putting his signature on a treasured disc belonging to Auerbach, a ZZ Top devotee and today’s most prominent practitioner of blues-influenced garage rock. Separately, the men represent two badass pinnacles of rock and roll, demonstrating through their music, guitar work and choice of instruments how the blues has influenced—and continues to shape—music, well into the 21st century. Together, Gibbons and Auerbach are a blues summit—a pair of experts who can riff on the contributions of blues legends like Hound Dog Taylor, Lightnin’ Hopkins and Junior Kimbrough, while discussing the finer points of the vintage gear that helped shape the sound of classic blues records.

Although the occasion for Gibbons and Auerbach’s meeting is an interview for Guitar World, it might as well be a record collectors’ convention, a guitar swap or a blues-fan nerd-out. The conversation embraces the gleaming faux-silver-pickguard-bedazzled Silvertone charmer that Gibbons has brought along with three other guitars, plus a pair of vintage Kustom speaker towers that he and bassist Dusty Hill are using on ZZ Top’s current tour for Texicali, their new back-to-basics four-track EP. Gibbons and Auerbach also extol the charms of vintage vinyl and the sounds and rambunctious spirits of a host of bygone blues six-stringers, including McDowell, Lil’ Son Jackson, Junior Kimbrough, Hound Dog Taylor and, of course, Lightnin’ Hopkins, whose music cuts close to both men’s bones (see sidebar).

Gibbons and Auerbach have been friends for nearly a decade, and when they get together it’s like an exuberant reunion of long-parted pals. Despite the difference in their ages, the two have many similarities that belie the distance between their generations.

Gibbons got his start in the mid Sixties playing gnashing guitar in the Moving Sidewalks, a group that breathed the same dusty psychedelic Texas air as the legendary Roky Erickson and opened for Jimi Hendrix and the Doors. He educated himself in the ice-pick guitar styles of protean Texas bluesmen like Hopkins and Jackson and their Louisiana neighbor Frankie Lee Sims, plus the laconic hypnosis of Jimmy Reed and Eddie Taylor. Since then, Gibbons and ZZ Top have recorded 15 studio albums and 42 singles onto which he has cut one of the greatest guitar tones ever to bark out of an amp.

Auerbach, who has pasted some of the past decade’s most evil and snarling guitar sounds onto seven studio albums by the Black Keys, started clean—playing bluegrass with his family—but set out on a personal quest to explore the same dirty secrets of the blues as Gibbons, albeit 30 years later. For him, discovering the serpentine melody lines of Mississippi hill-country guitar anti-hero Junior Kimbrough was like being struck by the other kind of lightning. It jolted him out of college and into cofounding the Black Keys in Akron, Ohio, in 2001. With three Grammy Awards, a Platinum album for 2010’s sonically daring Brothers, a solo disc, March’s sold-out Madison Square Garden concert, an April headlining gig at California’s eclectic Coachella festival and a near-ubiquitous presence on TV and in film soundtracks, Auerbach and the Black Keys are burning their names into rock’s Big Black Book.

Over the course of nearly four hours Gibbons and Auerbach will laugh, talk, pick out licks and share the camera’s focus with Auerbach’s big brown dog, Bella, a natural charmer who saunters through the studio greeting visitors like Easy Eye’s unofficial hostess. They’ll also take four minutes to listen to a cut Auerbach’s been producing for Los Angeles–based songwriter-guitarist Hanni El Khatib that’s gritty, haunting and reverb-drenched enough to be a lost gem from the vault of Chicago’s Chess Records. Which prompts our opening question:

Have you guys ever recorded together?

- BILLY GIBBONS: Oddly enough, we were brought into the studio under the auspices of our buddy [producer] Rick Rubin. We had developed a friendship aimed at just taking the time to talk about the kind of stuff we’re talking about now: Lightnin’ Hopkins and Lil’ Son Jackson, Gold Star Records out of Houston... So much of that stuff was primitive by today’s standards but did a fine job then.

- Anyway, Dan and Patrick [Carney, the Black Keys’ drummer] and me got together in California in the studio and spent a couple days knocking around, and it brought us even closer together. The funny thing was, we were having such a blast, and the richness of the exchange had Rick Rubin speechless. He just kept saying, “Keep on, keep on…”

DAN AUERBACH: Rick had us doing this weird thing where he would throw out an idea and we’d start jamming. Patrick and I would leave going, “What just happened?”

GIBBONS: Rick has got this unwarranted reputation for taking forever to get a project done. He’s quite the opposite. I think in the course of one day we had starter-kit ideas for about 20 songs. Rick would come out of the control room and go, “Well, we’ve got that. Let’s do something else.” He’d look around and say, “Patrick, give me a beat!” It was, like, hyper-pedal…

How did you guys meet?

AUERBACH: Billy came to one of our shows in New York City, at Irving Plaza.

GIBBONS: Yes, that was early on, but previous to that was the Paramount in Santa Fe, New Mexico. What drew me there… I was living out there for a time, and my buddy Freddie Lopez, who is an actor but also has a mind for sounds, said, “What are you doing tonight?” I said, “Not much. What do you have in mind?” He said, “There’s this group called the Black Keys.” “The Black Keys?” I said. “Man, I can’t believe you’re bringing this up. Just last week, I was in Los Angeles and the filmmaker David Lynch,” who is partnered up with his musical buddy, um…

Angelo Badalamenti?

GIBBONS: Yes! Well, they had come to the house, and Lynch said, “I just wanted to bring you this,” and it was the first Black Keys record.

AUERBACH: We were touring at that point in the minivan. I remember listening to Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes as we were rolling over the hills at night, seeing the lights of Santa Fe in the distance.

GIBBONS: Upon hearing the Black Keys for the first time, it resonated. We stuck around after the show that night and I made it a point to get to know Dan and Patrick. I said, “I don’t know how you guys do this, but don’t change it. It is working.” The room was rocking; the walls were rattling. We got to talking about so many like-minded things. It came as no surprise that much of the inspirations that lead me to continue to do what I do are the same things that lead Dan to do what he does. So we connected. The brush fire had started.

AUERBACH: Now it’s a bro-mance that’s taken years to blossom.

GIBBONS: What I enjoy about watching the Black Keys is the sense of abandon. It’s wonderful to be embraced and appreciated by many, many fans that get it and want to be part of it. At the same time, Dan and Patrick are being propelled to deliver something.

There is something remarkably mesmerizing about getting to do what we get to do. It’s beyond design. We’re just drawn to it. And there are those moments when, I don’t know how to describe it, but you’re just enjoyably drawn to get it out. It’s beyond yourself.

Billy, you’ve been eyeing the wall of about 600 albums in the studio’s office, and Dan, you’ve kept discs spinning since Billy arrived…

GIBBONS: If we can address the value of vinyl… Upon entering Dan’s Easy Eye Studio, I was drawn immediately to the Macintosh tube amp and the turntable, and it was in the groove. The rawness and the richness of music on vinyl almost went away, but it still seems to be on a lot of people’s radar, and for good reason. It does something different than more accessible means of music playing, like MP3 players and downloads and whatnot. You get in front of these archaic contraptions that go ’round and ’round. It’s mesmerizing, not only to look at but to sit back and experience. Wouldn’t you agree?

AUERBACH: Yeah, yeah. There’s nostalgia there, for sure, but it also sounds fucking great. Everything sounds really good on vinyl, if you’ve got a nice setup. I’ve got a bunch more albums at home.

Billy, do you have a big vinyl collection?

GIBBONS: Oh yeah. Unfortunately, it had to be rescued. We were in England and I was notified to call my assistant, Denise. She said, “Well, there’s been a horrific rain storm and that flat roof of your condo sprung a leak. I was retrieving the mail and I saw something that looked like a garden hose spraying straight into the room.” She called the handyman and they were able to put the valuables aside, but part of the rain went right into a column of vinyl.

Water doesn’t hurt a vinyl record. Put it into a dishwasher and you’re fine. But the paper began to mold and my secretary, being rather protective, decided it was unsafe and threw them all away. I was able to rescue several garbage bags. It was just one column, but it happened to be a column of favorites. I ordered up a bunch of plain white sleeves to put them in and they were fine.

What are some of your favorite titles on vinyl?

AUERBACH: It changes every day. I always obsess about something and listen to it over and over and over again.

GIBBONS: I’ll turn one track into a two-hour listening session. It’s that obsessive thing. I share it with Dan—the passion and obsessiveness that can enter one’s pathology when it comes to vinyl and tubes and all this crusty stuff.

I have a longstanding buddy who is a true audiophile and has invested a lot of time and money, to the point where he bought a platform that was invented to stabilize electron microscopes from the rattling as the Earth spins…

AUERBACH: The rattling of the Earth’s rotation? [laughs]

GIBBONS: It was causing this low-end rumble that he was able to perceive. Given the power of an electron microscope—and at 100,000 times magnification, it better darn well be stable or it’s going to be very fuzzy—he decided that if he put one under his turntable it would be a little more precise.

AUERBACH: Shit. Just have one of those built into the soles of your shoes. Check this out… [He pulls another single out of a case.] Here’s Hound Dog Taylor’s very first 45, before he had his band the Houserockers: “Christine” backed with “Alley Music,” on the Firma label.

Did you know that Hound Dog Taylor left Mississippi with the Ku Klux Klan on his trail? They wanted to lynch him for seeing a white woman, so he took off at night and hid by crawling through drainage ditches until he got to Memphis, where he lit out for Chicago.

GIBBONS: Well, that brings up something really interesting. How did Memphis become this musical melting pot? As the African-American exodus to leave Mississippi started building up steam to head up to Chicago—where it was a little more open and job opportunities were better—very few people had enough money to have an automobile or even to get a bus ticket, so walking out of Mississippi was the way to get on your way. From the Delta, Memphis was about as far as you could make it on one set of soles. That was a great stopping spot, with Beale Street and the nightlife. The attraction must have been beyond imagination.

AUERBACH: Think about how exciting it was before the days of being able to check shit out on the internet. All you would hear were stories, and as they were told and retold they’d get grander and grander. Can you imagine how the stories about what it was like hanging out in Memphis sounded in rural Mississippi?

GIBBONS: I heard a story: Freddie King and Little Walter walked…you know the [Howlin’ Wolf] song “I Walked from Dallas.” I think Freddie did a version. Word has it that Freddie King and Little Walter walked from Texas to Chicago. Maybe not all the way, but significantly…

One of the things you both appreciate in classic blues artists like Little Walter and Lightnin’ Hopkins is their expressionism—the idea of changing and moving on to new ideas when you feel it in the music, not because it’s dictated by form.

GIBBONS: It’s become acceptable to address that which is emanating from a spiritual and soulful spot within—something that doesn’t necessarily have a requirement to be perfectly boxed in forms of 12 bars or 16 bars—like a math problem.

AUERBACH: When did that happen? Did British blues do that?

GIBBONS: Well, yeah.

AUERBACH: Did you like British blues? You know, like the John Mayalls and the Peter Greens?

GIBBONS: Yeah. The British have a tendency to take whatever subject they plow into down to the genetics, and blues was no exception. But they were getting blues records much, much later, when the art form itself here in the United States ran the risk of being abandoned. Then the Rolling Stones, the Pretty Things, a lot of these groups—especially John Mayall, who was the leading exponent of hardcore electric blues experimentation—made it so appealing and repopularized the art form. I call it the Great Salvation. They are to be credited for the salvation of this art form that was nearly extinct.

AUERBACH: I could never get into British blues. I don’t know why. I grew up listening to Memphis recordings and Texas stuff, and then I couldn’t understand the British approach. I just didn’t get it.

But didn’t you come up playing bluegrass, which requires so much precision?

AUERBACH: Bluegrass was more about the harmonies for me, and vocal group stuff, like the Stanley Brothers. It’s about songs. And bluegrass is soul music—white soul music.

GIBBONS: Ah… the Stanley Brothers. That harmony work was so perfect. When you analyze the complexity of where the melody would go, and to have three guys intuitively able to follow, it’s just…beautiful.

You guys not only have musical tastes in common, you have a shared interest in a certain kind of guitar tone. You’re always looking for dirt. Where does that come from?

AUERBACH: It was listening to these records and I’d think, How did Elmore James get his guitar to sound like that? You couldn’t go to Guitar Center and plug into an amp and get that sound. I had to dig for it. It’s hard to say, but still to this day, I listen to some of those old 45s and just can’t believe the sounds they got. And they were using weird shit. Little Walter was using that weird Danelectro amp with six eight-inch speakers. Electric music wasn’t defined yet. Companies were making weird stuff, and those guys were taking advantage of it.

GIBBONS: It’s no secret that, even then, Fender and Gibson kind of led the pack as far as high-quality instruments, and after them you’ve got what maybe even then would be considered lesser instruments, only because they were more affordable. And those are the instruments that were largely present on vintage blues records, making these sounds that are so appealing. I mean, they’re magnetic.

In 1950, the biggest amp you could get was no bigger than a tabletop radio. Imagine trying to be heard in a joint with people screamin’ and shufflin’ their feet and bottles breakin’. You had to take that amp and turn it up all the way. When you’d get up past that “acceptable” point, you’d get into the land of distortion, which is where it really gets groovy. And I don’t think it was intentional. I think they just wanted to be heard.

Getting back to the idea of performances coming from a soulful place within: do you think that happens much in contemporary music?

GIBBONS: You don’t see it as often because the more popular outlets, like TV, are designed to be predictable. That’s to say, it’s easier to see a soulless…no, it’s easier to see something that may lack what you are describing, but I feel there are probably more soulful performers under the radar.

AUERBACH: With record labels getting smaller, record sales going way down, local record shops closing up, it’s harder for people to find the stuff that’s under the radar but still as easy for people to find all the big pop stuff. That stuff’s not for transcendence; it’s kid stuff. It’s for people who buy one or two CDs a year. Music is not their thing.

The internet makes finding interesting music and soulful music easier, but you have to search for it. I have a buddy who used to own a magazine in California who’s the first guy who told me about YouTube. He said, “You’ve got to check this out. It’s gonna be really big.” He sent me a link to a video by Parliament-Funkadelic playing at a Boston television station in 1969, and they were going bananas. It was insane. I’d never seen that footage before, and it was the coolest shit ever. YouTube is amazing for a guy who used to have to go to the public library and have them search for shit for me, and half the time they’d never find it.

GIBBONS: Because of the overwhelming amount of stuff that’s out there on YouTube, the real challenge is just sifting through to something where you’re bonused by the discovery. How about [blues and gospel legend] Sister Rosetta Tharp?

AUERBACH: She was a monster…on a white SG with triple pickups. [Gibbons picks up his phone and plays a video of Tharp’s performance of “Up Above My Head,” which includes a burning solo on that SG. Auerbach responds with a clip of black South African guitarist Hannes Coetzee playing acoustic slide guitar—and beautifully—with a spoon held in his teeth. Gibbons laughs.]

GIBBONS: There’s an example of “You can’t do that.” “But I am!” [laughs] Bonused!

Do each of you have a favorite guitar right now?

AUBERBACH: I’ve been playing my white Kent a bunch. We’ve been doing an album in here over the past week and we’ve used that on every song. I bought it in a guitar shop in San Jose. I’ve had it about a year and a half.

GIBBONS: The tremolo arm on that is the sweetest primitive setup. This ain’t rocket science. It’s just a bending piece of metal. Dan told me, “I bought a ’53 Gibson Gold Top and this Kent…”

AUERBACH: At the same shop.

GIBBONS: On the same day. And he said, “I don’t know if I’ve played that Gold Top yet.” There’s a great guitar player here in Nashville, Mike Henderson…

AUERBACH: Oh, I love him. [sings a line from Henderson’s “When I Get Drunk”] “When I get drunk, who’s gonna carry me home…”

GIBBONS: Well, he’s had one guitar and one amp that he’s played as long as I’ve known him, which is a significant amount of time.

There are two premises to aspire to. Number one: learn to play what you want to hear. And two: know what you want to hear and then go after it. If that’s the platform you’re playing from, it doesn’t matter what you’re playing.

In this business, I know it’s popular to have the most valuable or most esoteric guitars. And there’s a lot of stuff out there. Just about the time you think you’ve seen it all, go to one of these guitar gatherings and somebody pops up with the mystery amp or guitar. But it comes back to familiarity. I mean, who would think that if you take a Kent—an early low-tier budget guitar—and start banging on it, oh yeah, you got the goods?

The harmonica player Shaky Walter Horton [a.k.a. Big Walter] took a job as a cab dispatcher up in Chicago—not because he needed that gig or wanted to become a cab dispatcher; he wanted the microphone. After about two weeks, they said, “Okay, this guy’s good.” Then he got wire cutters, cut the mic and split. And that was it.

AUBERBACH: The thing I’ve learned about guitars and amps is that it’s fun to collect them. I love that stuff. But it doesn’t matter one bit what instrument you play. Lightnin’ Hopkins could pick up anything and still sound like Lightnin’ Hopkins. Usually when you fall in love with a guitar it’s because it’s lightweight, it sits nice when you put it on, the headstock doesn’t weigh it down. Sometimes it’s even more about comfort and whether it feels like it could be an extension of your body than about sound.

GIBBONS: In closing, Dan and I could warrant this: get one of each guitar you love, and then turn them up loud.