Joe Bonamassa: Blues Deluxe

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Originally published in Guitar World, February 2010

Joe Bonamassa is fresh off a hit album, a live DVD and a badly broken

heart. With his career on the hot track and a new CD on the way, the blues guitarist refl ects on his gains and losses, and what is yet to come.

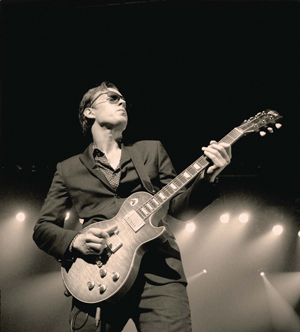

Joe Bonamassa is sitting in his regular perch in the front of his tour bus as it rolls through the Illinois countryside. It’s 2:30 in the morning, and we are driving to Chicago from Peoria, where he just performed before a Civic Center crowd of 1,000. In 12 hours he will walk into the grand old Vic Theatre to soundcheck for a sold-out show. The rest of his 10-member band and crew have slipped into their bunks for some quiet time or sleep, but Bonamassa is sipping red wine and reflecting on his career.

Though he’s just 32, Bonamassa has been on the road for almost 20 years. A prodigal talent who could shred the blues with remarkable fluidity as a kid, he seems to be hitting his stride now with a series of successful CDs and DVDs that have raised his profile, elevating him from clubs to theaters and putting him on the cusp of something grander.

It’s been a long and difficult journey. Over the years he has gone from overseeing the entire operation himself (including driving the band around in a van) to having a veteran professional tour manager that supervises a small road crew. And he has done it all by taking control of his career in partnership with Roy Weisman, his manager of 18 years. They now handle everything in Bonamassa’s career, from releasing his music to booking his shows, and seem to have found a stable path through the treacherous, ever-shifting landscape of the contemporary music business.

Bonamassa has a lot to be glad for. His last CD, The Ballad of John Henry, stood atop theBillboard Blues Albums chart for six months after its debut. This past September, he released the DVD Live at the Royal Albert Hall, which features his band blazing through a set at the sold-out London landmark, complete with an appearance by his hero Eric Clapton. His next CD, Black Rock, is already in the can.

This would seem to be the moment at which he could pat himself on the back and reflect on how far he’s come. But as his tour bus rolls through the darkness, Bonamassa is considering what he’s sacrificed: a chance to build a stable home life around a lasting relationship.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Living this life, even if you find the true love of your life, chances are you’re gonna burn them out being gone,” he says. “What good is it to be in a relationship when you’re gone for months on end or they come out with you and sit on the bus with nothing to do? I’ve had two long-term relationships in 10 years, and it burns them out.

“Last year I thought I found the one, so I still think it’s possible. I was on cloud nine. You could not have given me the blues if you tried. Six months later, after this huge movement of houses, people, everything—I moved from L.A. to Athens, Georgia—it fell apart, and I was at the lowest point of my life.”

In the tried-and-true tradition of the blues, Bonamassa turned to his music for healing. He poured the emotions of this spectacular disaster of a relationship—the ups and the downs—into the songs of the album he was in the midst of recording. The Ballad of John Henry was recorded in two sessions, four months apart—a third of a year during which Bonamassa’s moods spanned the gamut of human emotions.

“I was as happy as I’ve ever been when we did the first sessions for the album and as down as I’ve ever been when we did the second,” he says. “I could not have been in a worse place.”

Bonamassa’s struggles and this dark period produced some of his deepest, most personal songwriting, notably “Last Kiss” and “Happier Times.” “I think these are the most heartfelt songs, with the best lyrics, that I’ve ever written,” he says.

Producer Kevin Shirley helped make sure that Bonamassa’s emotions informed the music as much as they did the lyrics and vocals. “He was so obviously distraught when we cut ‘Happier Times,’ ” Shirley recalls. “We tracked it, and then I took him aside and said, ‘Play everything you are feeling on that guitar.’ I left him alone and just let him play and play with the guys, playing the changes over and over, and later I edited that down into the solo. It was pretty intense. I can still feel that emotion when I listen to the song. And amazingly, he says that he doesn’t have a memory of playing it at all. He just poured everything into the solo.”

Bonamassa’s successful integration of his pain into the music also represented a maturation of his approach to music. He has had terrific chops and an almost freakish ability to play hot-rodded blues rock almost since the day he played his first gig, at age 11, after sitting in with guitar greats like Albert Collins and Danny Gatton in his hometown of Utica, New York. A year later, B.B. King took him under his wing, and he made his major-label debut, as a member of the band Bloodline, when he was still a teen. Bonamassa has evolved into a deeper, more well-rounded musician. His licks are no less impressive, but now they are in the service of something greater, working in a context that appeals to those outside the guitar community.

This transition began in earnest in 2006 when he first entered a studio with Shirley, who had produced the Black Crowes and Aerosmith and is probably best known for having mixed Led Zeppelin’s How the West Was Won and the group’s eponymous DVD, both released in 2003. Shirley took a much more expansive view of Bonamassa’s music and potential than anyone had previously.

“From the first time we spoke, Kevin didn’t care what I could do well,” Bonamassa says. “He cared about what I needed to work on, and he wanted to challenge me. He suggested a lot of songs and situations I never thought would work, and we tried them, and it took us to a whole new place and a whole new level.”

Shirley recalls going to see Bonamassa for the first time, in a small club outside Chicago. He was impressed, but not exactly wowed. “It was clear to me right away that Joe was a great guitar player, but I wasn’t sure where he was taking it,” he says. “I went on the bus, and he asked what I thought, and I was just totally honest. I said, ‘I think that you’re very good, but you’re on a bit of a nowhere journey. If you ever want to think outside the box, then let’s do something, but it’s going to take you places you might not be comfortable with, and you’ll have to trust me.’

“He was a little taken aback—he had just played a gig and had 50 adoring fans around him—but he called me about a week later and said, ‘Okay, I’m ready. What do you want to do?’ ”

Shirley’s first thought was that Bonamassa should expand beyond the power-trio lineup he had been playing with for years. He wanted to bring in some new and different musicians, starting with drummer Jason Bonham and bassist Carmine Rojas, a veteran session and road musician who had performed with David Bowie, Rod Stewart and countless others. Shirley says, “These guys are great musicians, but more importantly they had the experience and musical respect to let Joe be the star.”

Bonamassa says, “The thing that was so great about working with Kevin is he opened things up without trying to steer me away from blues and the music I loved and wanted to perform. He saw more possibilities for what I was doing, but he wasn’t trying to change me or make me into something I wasn’t, and it was all good from the start. The first thing he did was call Jason Bonham, and working with him was great. I am just not the kind of guy who would do that myself.”

That recording became You and Me, Bonamassa’s third album to be released on his own J&R Adventures label and his first to debut atop the Billboard Blues Albums chart. Bonamassa has never been a blues purist—the title track of A New Day Yesterday, his debut CD, is a Jethro Tull song—but on You and Me he expanded his usual mix of original and cover tunes further. In one instance, he took on Led Zeppelin’s “Tea for One,” inspired by Bonham’s drumming. It was evident then that he had taken a subtle but definitive turn, one he furthered by adding Rojas and keyboardist Rick Melick to his touring band, along with drummer Bogie Bowles (who had previously worked with Kenny Wayne Shepherd). The result is a more professional band and a fuller sound that puts a stronger focus on Bonamassa and the songs.

“I did not and still don’t fear thinking outside the box and changing what we’re doing,” Bonamassa says. “I had created my own little house, and it was really comfortable. When Kevin first came to see me, it was in a sold-out blues club—300 people—and we thought that was pretty great. Four years later, we’re at the Royal Albert Hall with 5,000 people there and Eric Clapton coming out to play. The impact of these records with Kevin on my career is incalculable.”

Bonamassa has always had a knack for finding great material, and he has continued to do so even as his songwriting has grown stronger. His next CD, Black Rock, which will be released in March, was recorded in Greece and features local musicians enlivening Leonard Cohen’s “Bird on a Wire” as well as a romp through “Steal Your Heart Away,” an old tune originally done by bluesman Bobby Parker. The song was recommended to Shirley by Robert Plant, who said Led Zeppelin rehearsed it in their earliest days and that he regretted not recording it.

But the guitarist has also become extremely prolific. In four years, he has released four studio albums (including Black Rock), a live album and the Albert Hall DVD. If he were still on a major label, as he was for his 2000 debut, he likely would have put out one or two of those projects. “Taking control and putting out our own product has given me a lot of freedom to keep trying different things and recording when we’re ready or just want to try something, rather than waiting for someone else to tell me it’s time,” he says.

Shirley has grown increasingly impressed with Bonamassa and Weisman’s business acumen and willingness to follow their instincts and try new things. “Musically, Joe will listen to ideas and let something play out to see if the vision develops and pay off,” Shirley says. “And he’ll know when to pull the plug and when to keep riding something. He and Roy have approached the business in a similar way. They’ve been mercurial enough to move with the demands of a fast-changing industry. They see every aspect of every cog in the wheel as leading up to something else. They pay for everything out of their pocket, and we have budgets better than a lot of big labels will give you now. And it’s all worked. People in this collapsing music industry are now referring to this as the ‘Bonamassa model’ and calling me to discuss it.”

This acquired business savvy is not in any way antithetical to great musicianship. Bonamassa says that B.B. King’s big advice to him was to know how to do everyone’s job and always take care of the money yourself. Still, running a tight ship would be meaningless without great music, and Bonamassa has continued to grow. Rojas says, “The thing about Joe is he’s so talented and so ready to explore. It makes it really fun and constantly challenging to play with him. If you crack open the door even just a little bit for him, you know he’s going to open it up and see what’s there.”

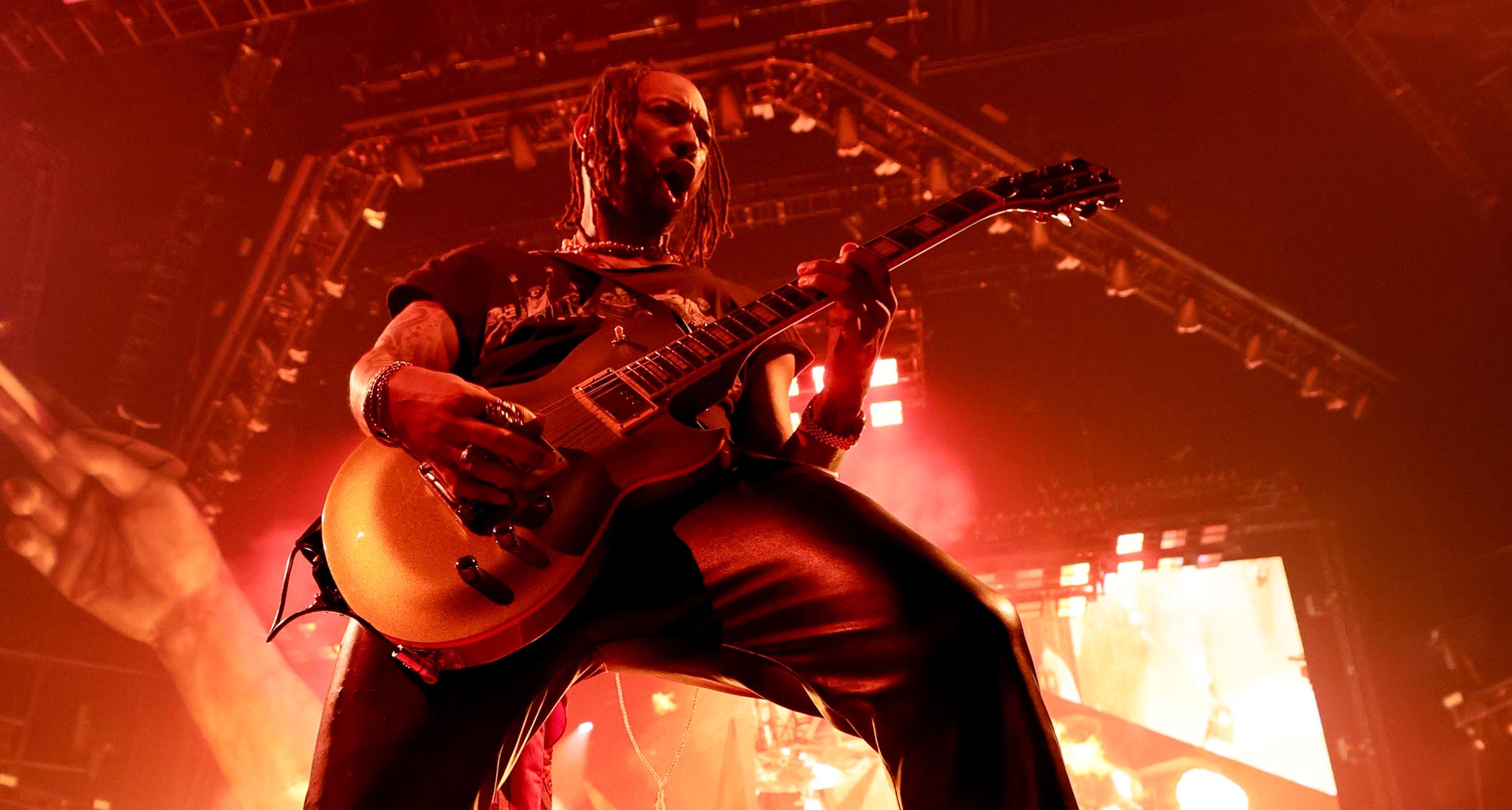

Following his Chicago performance at the Vic, Bonamassa was ready to do a little more exploring. He and Weisman hopped into a van and drove a couple of miles north to the Riviera Theatre, where Gov’t Mule were performing. An onstage jam between these two old friends had been orchestrated, and to facilitate it, a quick rehearsal had been held earlier in the day during Mule’s soundcheck. One of Joe’s beloved Les Pauls had been placed alongside Warren Haynes’ arsenal, ready for action.

Bonamassa arrived for the last two songs of Mule’s first set, thundering performances from their new CD, By a Thread, that whipped the crowd into a frenzy. Haynes and the band took their break and headed down to their dressing room, Bonamassa stood hesitantly in the background for a moment before following them, acting more like a polite interloper than a guest star.

In the dressing room, Haynes and Bonamassa greeted each other like long-lost friends. They first met more than 15 years ago when they co-wrote a couple of songs for Bloodline’s 1994 debut, on which Haynes also played. After that band fell apart, Bonamassa recorded Haynes’ “If Heartaches Were Nickels” on his solo debut, and the song remains a staple of his live shows. Yet despite the connections and a strong mutual respect, the two had done precious little public jamming, and both were excited.

Two songs into Gov’t Mule’s second set, Haynes called for Bonamassa, who strode onstage to the cheers of the packed house. Mule fans always know to expect the unexpected—no one enjoys bringing special surprise guests onstage more than Haynes—and they were in for a special treat. Over the course of two songs—“Feel Like Breaking Up Somebody’s Home,” a soul song popularized by blues guitar titan Albert King, and the original instrumental “Sco Mule”—Haynes and Bonamassa engaged in a playful, virtuoso blues guitar dialogue that played out like an ecstatic ad for Gibson guitars. Throwing sparks at one another and taking flight on one long complementary journey, the two guitarists made their Les Pauls sing in eloquent, tube-drenched harmony.

Afterward, Bonamassa and Weisman piled into the van and headed back to the Vic. The bus was waiting, gassed up and ready to push off for St. Louis, where the endless tour would continue 600 miles later. Rojas and Melick were waiting on the sidewalk, eating French fries and talking to some lingering fans. Bonamassa greeted them all, then everyone said goodbye and piled onto the bus. The door pulled shut, and the vehicle pulled away from the curb.

They had six or seven hours to drive, and most of the guys were no doubt tucked away in their bunks before long. Bonamassa was probably in his seat upfront, sipping wine and looking out the window again, thinking about the miles behind him and the distance yet to cover.