K.K. Downing: “I don’t want to discard my heritage, my legacy, who I am, what I sound like and my style of writing”

The Metal God opens up about his Judas Priest exit and rebirth in KK's Priest, and explains why he is a Priest for life

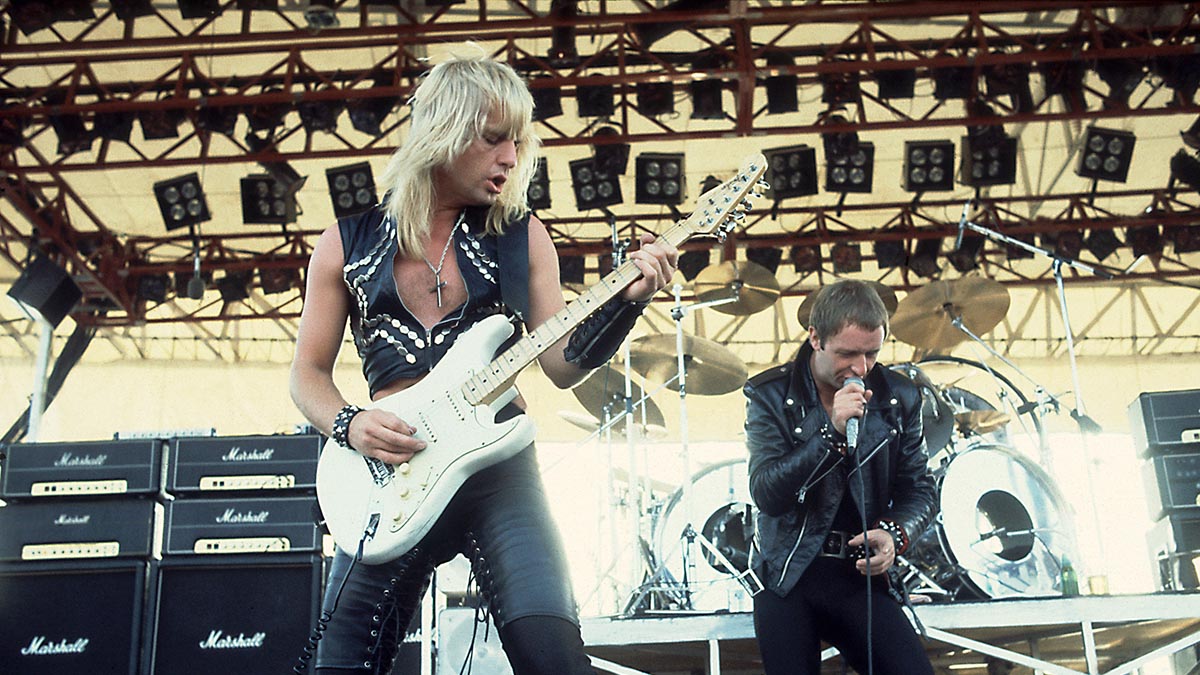

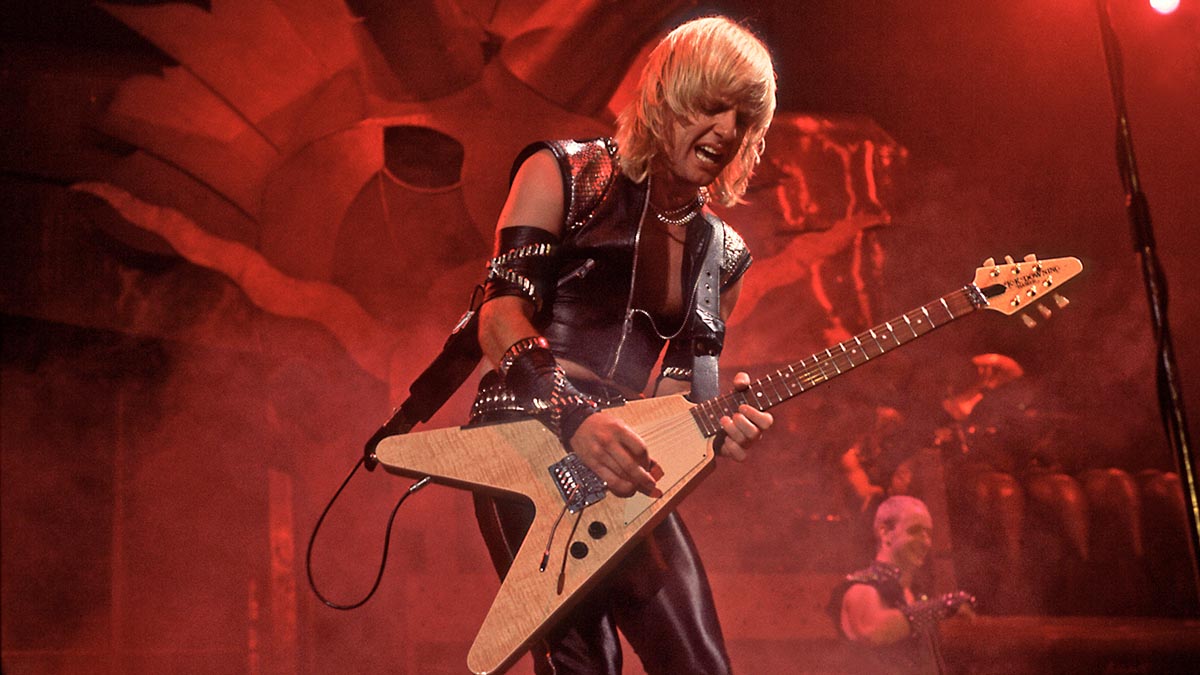

For anyone who thinks Judas Priest co-founder K.K. Downing ran out of musical steam and mental energy when he “quit” the band in 2011 and was replaced by Richie Faulkner – you’ve got another thing coming.

Downing’s new band, KK’s Priest, is pugilistic and propulsive, rife with instantly engaging riffs, blazing solos and memorable hooks. Does it sound like Judas Priest? Sure it does, but who has more of a right to make music that sounds like everything else he’s done than one of the forefathers of Judas Priest and the metal movement?

KK’s Priest’s debut album, Sermons of the Sinner, the first major metal project on which Downing has played since Judas Priest’s 2008 operatic Nostradamus, is a feast of palm-muted riffs that burst into infectious, but not always predictable rhythms.

From track to track, the music conjures the multi-faceted strains of Sad Wings of Destiny, the anthemic surge of Screaming for Vengeance and Defenders of the Faith, and the jackhammer grind of Painkiller.

Beyond the album title, an unapologetic reference to Judas Priest’s 1977 fan-favorite Sinner, there are other musical and lyrical nods to Judas Priest, including the closing track The Return of the Sentinel, which nicks part of the opening lick from the 1984 song The Sentinel, and addresses the apocalyptic aftermath of a war fought by the main character.

Throughout, Downing writes and plays like he’s still a member of Judas Priest – not to thumb his nose in the face of his former bandmates, but to prove his metal might and cement his legacy – and he doubles down on Sermons of the Sinner by hiring ex-Judas Priest singer Tim “Ripper” Owens to front the band.

“I suppose consciously or subconsciously, I didn’t know whether this was the last thing I was ever going to do, so I wanted it to be very exciting and very metal,” Downing says from his home in the UK. “I think it’s a fitting example of what I’ve done before and what I plan on doing for quite a while. But you never know. I’m 69 now and I just lost my sister a couple weeks ago and she was 67. So, just in case this is it for me, I want it to be a lasting reminder.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

There’s probably only three guys in the world that can do what Ripper, Halford and maybe Bruce Dickinson can do night after night

Downing’s aspiration to create a barreling Judas Priest-style record that features a former Judas Priest singer and song titles that reference Judas Priest songs has rankled his former bandmates so much that they threatened to hit Downing with a cease-and-desist order to prevent him from using the name KK’s Priest.

They’re not the only ones to accuse Downing of heresy. Smack-talkers have called KK’s Priest a “desperate cover band” that threw together an album of “derivative” musical parts and hired a “Rob Halford clone” to play old Judas Priest songs live.

Downing is unrepentant about what he’s doing and insists that writing in a style that didn’t resemble Judas Priest would be disingenuous. Also, he has no regrets about hiring Owens, who certainly wails like Halford, but is also influenced by Ronnie James Dio and Philip Anselmo.

“There’s probably only three guys in the world that can do what Ripper, Halford and maybe Bruce Dickinson can do night after night,” Downing says. “I don’t know how they do it. It’s incredible. But I couldn’t have Bruce. I couldn’t have Halford. So Ripper was the obvious choice. We’ve made albums together, we’ve toured together and Ripper is a great guy. And, of course, he has been a Priest before” [singing on 1997’s Jugulator and 2001’s Demolition].

When asked if he was ever concerned that something on the album might sound too much like the material he wrote for Judas Priest, Downing snickers a little and points out that, having played in Judas Priest on 16 albums over 42 years, it would be difficult and inauthentic to try to write in a different style.

“I’ve always been a Priest, and this is why I’m sticking to my guns now,” Downing says. “There’s people [in Judas Priest now that] I’ve never met playing my songs and solos calling themselves Priests. Why can’t I be a Priest? I can and I am. So this is KK’s Priest, and when you look at the history of this music, I am a big part of the past as well as the present and the future.

“I don’t want to discard my heritage, my legacy, who I am, what I sound like and my style of writing. It’s there for the world for now and the future, and that’s my new path and my new journey.”

The Punishment of the Sinner

There’s a reason Downing sounds defiant and even arrogant when talking about Judas Priest. He left the band before its “farewell” tour because he didn’t feel comfortable playing with Glenn Tipton anymore. When he discovered the band wasn’t retiring after all, he says he expressed interest in re-entering the fold, only to be rejected and ripped off.

“Lots of things were happening and coming to a boil in 2010 [right before the band announced the career-ending Epitaph World Tour],” Downing says. “Rob [Halford] released two albums in that year and did a world tour, including Ozzfest, with his band [Halford] playing Priest songs. At the same time, I wasn’t particularly happy with the last couple of Priest tours I had done and I wasn’t terribly excited about playing the farewell tour.”

As the Epitaph tour approached, Downing got tangled in band politics, bad timing and blown opportunities. Between then and the release of his 2018 autobiography, Heavy Duty Days and Nights in Judas Priest, he revealed few details about the terms of his departure. Now that he’s out of the band and on his own with KK’s Priest, the guitarist is spilling the beans about the behind-the-scenes machinations that led to his permanent dismissal.

“I never wanted to be a part of a big, public spectacle,” he insists. “I just made it clear that I didn’t want to play the final tour. But then they continued, which I never expected, and they didn’t want any part of me, even though I was one of the only original members.”

Downing’s unhappiness with Priest circa 2011 had less to do with personality clashes than it did with what he viewed as the band’s waning professionalism. In his book, Downing revealed that he grew increasingly frustrated with Tipton in particular.

“On these last tours [I played with the band], it felt as if some petty one-upmanship was going on. Whenever we ended a song, Glenn always, always had to make sure that the last sound that anyone heard came from his guitar… On many occasions, particularly near the end, I felt that Judas Priest’s live performances were suffering.”

Today, he elaborates on the other major element that marred his final tours with Judas Priest. “Glenn was drinking beer before the stage and and on the stage between every song, and it was slowing us down,” Downing says. “It made the rest of us feel insecure because it’s just like if you drive in a car and somebody is drinking at the wheel – you just don’t feel comfortable.

“I know it’s rock and roll and everybody has a right to do it their way, but I like to be very efficient and I get off on the music being very tight, and it was losing some of that. And Rob was reading the teleprompter. We just seemed to be not the band that we were.”

For Downing, the final insult came when the band asked him to write for a five-track EP to support the farewell tour. “I thought that idea stunk and my voice wasn’t being heard,” he says. “I felt that they should have listened to my opinion because I had been there a long time and I had a valid opinion, but it seemed as though people were ganging up on me. So I thought, ‘Enough is enough. I’m out.’”

When Downing made it clear that he didn’t want to play the farewell tour, management asked him to send an official letter of resignation. Under contract, he was still a shareholder and director in the company, so he wanted to leave on good terms.

“As far as I knew, we would still be talking to each other to deal with the purse strings,” he says. “So I sent a letter saying I had given everything and I didn’t have anymore to give and I was retiring from the business, which wasn’t true because I went straight into a production job with other musicians.”

As the Epitaph tour approached, one of Downing’s close friends told him he was making a mistake and that he should contact the band and tell them he changed his mind and he’d like to play the tour to create a nice bookend for his career with Judas Priest.

Though he was resistant at first, Downing finally agreed and called bassist Ian Hill, with whom he had attended primary school starting in kindergarten. He asked Hill if he could see the setlist for the Epitaph shows and the bassist sent Downing the list, but his demeanor was icy and no one else on the Priest team would talk to him.

With Downing’s retirement letter in the file cabinet, Judas Priest issued a press release stating that Downing was leaving the band and had been replaced by “31-year-old guitar player Richie Faulkner… a great talent who is going to help set the stage on fire!”

In press interviews, the members mentioned that Downing was quitting the music business to operate a golf course he founded in Shropshire, on the Welsh border. In truth, Downing had no intention to stop rocking. Incensed by further comments that indicated the band would likely work on a new record after the tour, Downing sent a second, less-diplomatic letter to Priest management.

“I said, ‘Ignore everything in my first letter,’ because I felt like I was prostituting myself anyway. And then I said everything I really thought and explained what really made me not want to do the tour, and that’s what got me in trouble and why they shut me out.”

Downing didn’t do as well with his golf course as he did in Priest and was forced to abandon the venture and sell the royalty rights to 136 Judas Priest songs to Round Hill Music to pay off his debts. But he insists he never sold his share of the band.

When Tipton stopped touring in early 2018 because he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease, Downing suggested that everyone in the band cast aside their grievances and he would rejoin as the lone longtime Priest guitarist onstage. He was surprised to find that no-one wanted him back.

“When I was in the band, I was always the loyal Priest,” he says. “I didn’t leave for 14 years like Rob. I didn’t leave for six years to do albums like Glenn did – with [drummer] Cozy [Powell] and [the Who bassist] John [Entwistle] [in 1997 and 2006]. I never had my own websites selling my own T-shirts. All of my good music went to Priest. And so, if I did retire, why wouldn’t I be allowed out of retirement when there was an opportunity and a space?

“I was there before Rob and Glenn, and I was instrumental in re-introducing Rob back into the band after he did his other things, so why would he say, ‘No, you can’t be a member of this band anymore,’ even though there was an opening? It doesn’t make sense.”

Instead of welcoming Downing back into the fold, Judas Priest immediately hired the co-producer of their 2018 album, Firepower, Andy Sneap [Sabbat] to play guitar on the tour alongside Faulkner. Then, Downing says, the group’s handlers told him he wasn’t entitled to any future band income.

“They didn’t just close the door and shut me out,” he says. “They tried to deny my contributions to the band. They tried to take all the revenue from me and not give me anything, not pay me anything. I begged them not to go the legal route. I said I’ll come down, sit around the table and discuss it. They said no.”

Now Downing and his former bandmates only communicate through lawyers, and the longer the conflict continues the more confusing the scenario becomes. Downing feels that by denying him money he is owed, his former bandmates are punishing him for disagreeing with them and for being honest about what was happening in the band before he left. It’s not just vindictive, it’s cruel.

I begged them not to go the legal route. I said I’ll come down, sit around the table and discuss it. They said no

“They want to take everything away from me that I actually have an entitlement to, really, which is the right to the band name, the right to the imagery, certainly the rights to the T-shirts and things they sell,” he says. “With British Steel or Screaming for Vengeance, I was instrumental in creating those images and I was promised a share of what I was a part of, but now they and their lawyers are saying no, I’m not.

“So, even if fans buy a T-shirt with artwork from British Steel or Sad Wings of Destiny, they get the money and I don’t. So that was it, really. I had no choice but to continue as KK’s Priest.”

The Revenge of the Sinner

The rusty, hinged gate to KK’s Priest started to creak open on August 11, 2019, at Bloodstock Open Air festival in Walton-on-Trent, England, when Downing was invited to take the stage with Ross the Boss (ex-Manowar) about two months shy of the guitarist’s 10-year absence from Judas Priest (his last show with the band was October 17, 2009).

The group covered Fleetwood Mac’s Green Manalishi (with the Two-Pronged Crown) (which was on Priest’s Hell Bent for Leather), Breaking the Law, Heading Out to the Highway” and Running Wild. Then, on November 3, after one night of rehearsal, Downing, Owens, Hostile guitarist AJ Mills, bassist Dave Ellefson (ex-Megadeth) and drummer Les Binks (ex-Judas Priest) played a one-off show at KK’s Steel Mill in Wolverhampton, England, and lit up the packed crowd with the Judas Priest standards Hell Bent for Leather, Living After Midnight, Breaking the Law, Metal Gods, Exciter and more.

“That was great fun, and I got an appetite for doing it again,” Downing says. “But I said, ‘I’m not gonna try to put a band together around an album that isn’t there. So I shut myself away for Christmas 2019, sat down and started playing. And I was amazed at how fast it all came together.”

A week after Downing started working, he had completed the framework for the songs for Sermons of the Sinner. A few days later he finished the song intros, the main riffs, middle eights and melody lines, and had a lyrical and visual theme for the album. “It was like all this stuff was just waiting for an opportunity to come out of me,” he says. “It felt good and the ideas are still coming, so I’m already working on the next album.”

The cover art for Sermons of the Sinner depicts a priest in a hooded brown robe standing at the edge of the ocean, with rocky cliffs and foreboding storm clouds looming in the background. The priest looks down at a large open book he holds in his open right hand.

The front and back covers are decorated with golden “K”s. And in his left hand, the robed man holds a sash that reads “Priest.” Though the priest’s face is shrouded by his hood, the long blond strands that stick out from the sides make it clear who the religious figure is supposed to be. If the visuals seem provocative they’re meant to be.

“Those guys deceived the media and the fans for 10 years, and I’ve had to suffer the wrath of that,” Downing says in a calm voice that belies his frustration.

“I called the album Sermons of the Sinner because I became the sinner in people’s minds because they think I deserted them. That’s what they’ve been told, but that’s not what happened. So, hey, I don’t care what they say. I wish the guys all the success in the world, but I’m still a Priest and this is KK’s Priest and I’m moving forward.”

Those guys deceived the media and the fans for 10 years, and I’ve had to suffer the wrath of that

About a month after he plugged in the trusted Gibson and Hamer guitars he played for years in Judas Priest, Downing had a complete demo of Sermons of the Sinner, music, lyrics and all. Originally, he planned to deliver the album to his label in late April 2020, in time to schedule summer festival shows in Europe.

With the help of Owens, Mills, Voodoo Six bassist Tony Newton and Cage drummer Sean Elg (who stepped in after Binks suffered a wrist injury), KK’s Priest easily met their deadline, which was then pushed back substantially due to COVID, giving Downing and Mills extra time to fine-tune some of the guitar lines and hone the production.

When asked how he was able to write and complete a multi-faceted batch of songs in less than a month, Downing says composing comes easily to him, but when he was a member of Judas Priest he had to compromise, which delayed the completion of the songs.

“I’m so glad now not to have to collaborate with Glenn and Rob on songs,” he emphasizes. “I’m glad that if I think something’s good, it goes on the record. I get to play the amount of solos I should have always been playing on a record, which is good for me because I can do it. I don’t find any of it difficult.”

Almost every song on Sermons of the Sinner features two or three pyrotechnic solo parts, and the way they blend together, one after another, is reminiscent of the way Downing and Tipton used to feed off each other, especially when KK’s Priest launch into a harmonized lead.

“What I really love is that I could have written this album now, which I have, or I could have written it in the future. And I could have written it 20 years ago,” Downing says. “It’s timeless because it isn’t music for now, it’s music for forever. Judas Priest probably got caught up in trying to create songs to fit a time for a while. We tried to keep inventing. I think it’s more important to realize what works and stick to it.”

In addition to striving to recapture the glory sounds of vintage Judas Priest, Downing wanted Sermons of the Sinner to stand out at a time when fewer bands are playing incendiary songs with complex guitar solos, and that by sticking to his loaded guns, his accomplished playing will inspire a new breed of guitar bands.

He plans to continue pushing KK’s Priest as long as he’s healthy, but he knows that for metal to stay vibrant and captivating, younger musicians need to study their predecessors and grab the mantle.

“My advice to young bands is don’t try to reinvent the wheel because there’s already a fan base there and they already love this wheel,” he tells us. “You just have to give your interpretation or version of it.

“Don’t try to invent a new style of metal or a new genre of music or whatever because it’s all being done. But there are so many fans out there that know what they love so bands just have to provide more of that, but with their own identity.”

A quick glance at the Billboard rock charts doesn’t offer much hope. Yet Downing remains optimistic and points to Greta Van Fleet as possible saviors or a fading genre.

“We haven’t had a Led Zeppelin, so why can’t we have a bunch of younger guys that enjoy the band and are writing new songs, new material, and have a new face and a new voice?” Downing enthuses. “That gives me hope for what we’re doing. There’s a massive rejoicement in this album of our music and our legacy, which is an endangered species, in a way.

“So hopefully, KK’s Priest will help us rise again, and maybe some of the musicians who like it will get on board and want to be a part of this music and write material like this in the years to come so they can keep it going long after we’re gone.”

Leaving a lasting impression and remaining relevant have been objectives Downing has thought about more than usual over the past year. Recently, the rock world has lost such icons as Eddie Van Halen, Dusty Hill, Charlie Watts, Neil Peart, Alexi Laiho, Joey Jordison, Tim Bogert and early Priest drummer John Hinch, and every week it seems another rocker passes before his or her time.

“We’re losing friends too often,” Downing agrees. “That will probably accelerate as all of us get older and us dinosaurs fall off the edge of the earth. In 50 years, will we just be a page in a history book or will we still be kept alive by the new blood?

“I wish I knew right now which way it’s gonna go. I can only do my part to try to stay in people’s heads as long as possible.”

- Sermons of the Sinner is out now via EX1 Records.

Jon is an author, journalist, and podcaster who recently wrote and hosted the first 12-episode season of the acclaimed Backstaged: The Devil in Metal, an exclusive from Diversion Podcasts/iHeart. He is also the primary author of the popular Louder Than Hell: The Definitive Oral History of Metal and the sole author of Raising Hell: Backstage Tales From the Lives of Metal Legends. In addition, he co-wrote I'm the Man: The Story of That Guy From Anthrax (with Scott Ian), Ministry: The Lost Gospels According to Al Jourgensen (with Al Jourgensen), and My Riot: Agnostic Front, Grit, Guts & Glory (with Roger Miret). Wiederhorn has worked on staff as an associate editor for Rolling Stone, Executive Editor of Guitar Magazine, and senior writer for MTV News. His work has also appeared in Spin, Entertainment Weekly, Yahoo.com, Revolver, Inked, Loudwire.com and other publications and websites.