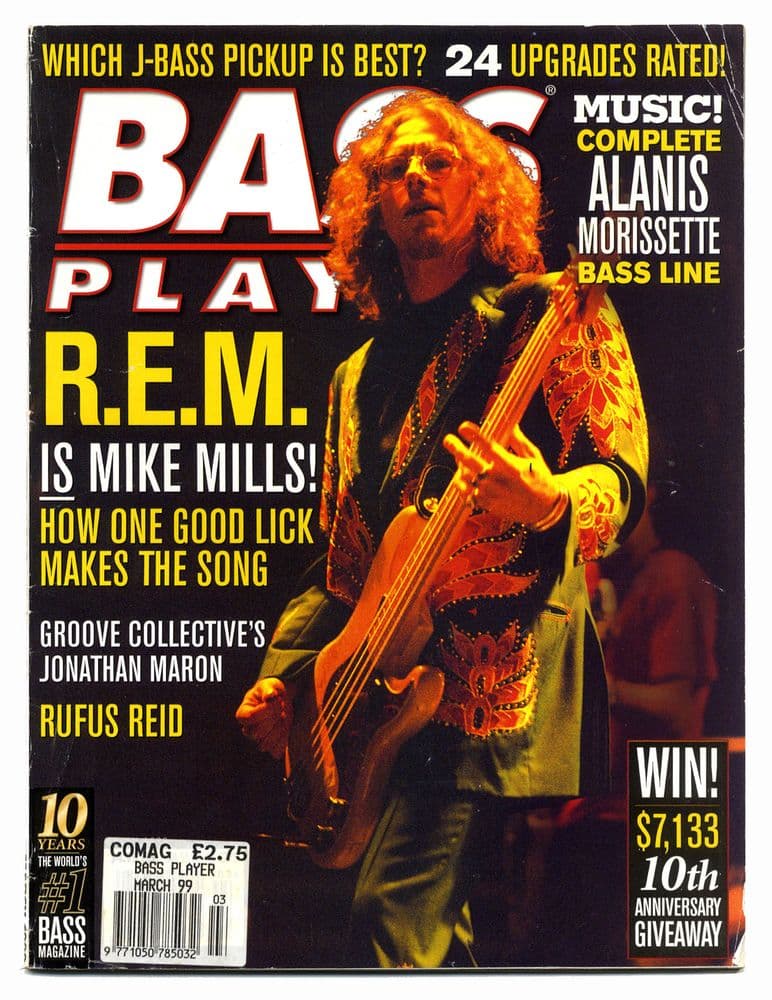

“Early on I discovered that the bass player decides the chord – not the guitar player”: R.E.M.’s Mike Mills on finding the perfect bass part and becoming a “one-bass guy”

From the Bass Player Archive: An interview with R.E.M. bassist Mike Mills

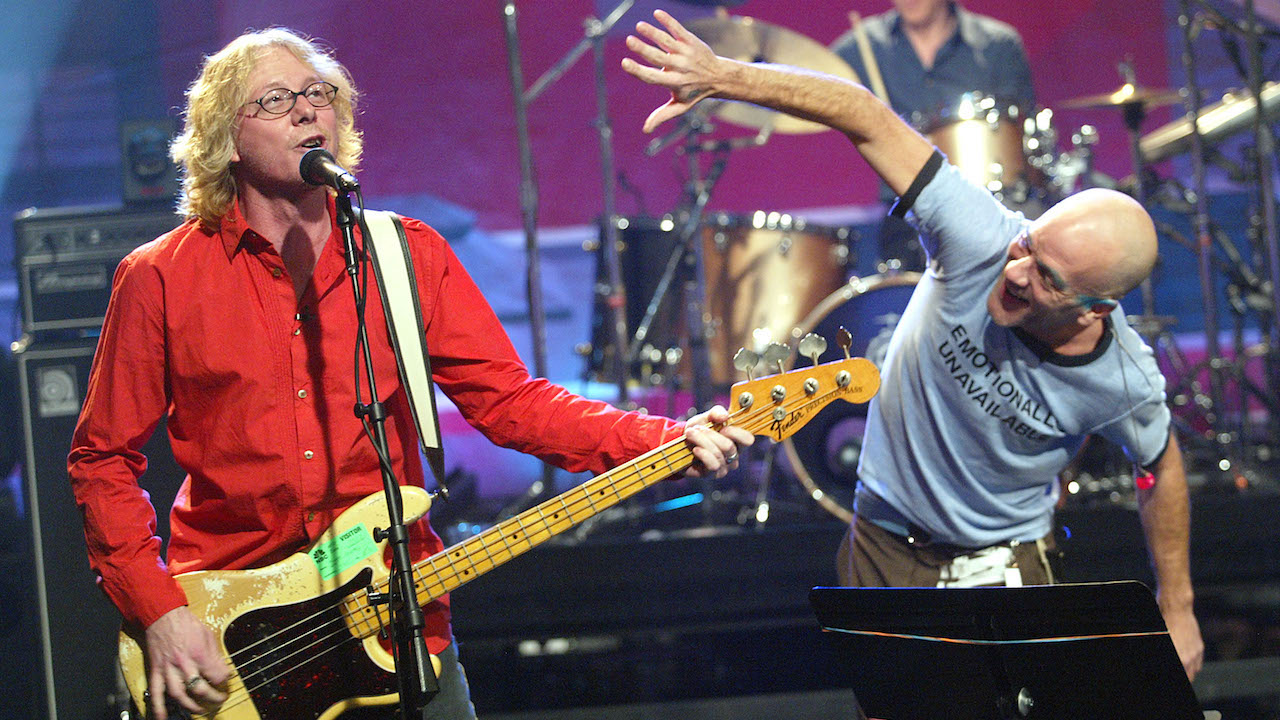

Mike Mills, the bassist and co-founder of R.E.M., now plays with his supergroup the Baseball Project – which also consists of guitarist Peter Buck. “We’ve all got our own things that we’re doing,” Mills told rollingstone.com “I think we’re all really happy with the way things are.”

Mills was speaking to promote the 25th anniversary edition of his former band’s 1998 album Up, which was released via Craft Recordings on November 10th. Up was the first that R.E.M. recorded as a three-piece following drummer Bill Berry's decision to step down without warning.

“It was more about not having Bill than about not having a drummer,” Mills told BP. “But we were prepared to do a record that didn't have much drums on it anyway, and when he quit it just accelerated the process.”

The ensuing ‘world tour’ involved hundreds of hours of press interviews, but only a handful of carefully selected club dates, where the trio was joined onstage by guest drummer Joey Waronker.

“I had a lot of trepidation since the bass player has to be more comfortable with the drummer than anyone else in the band,” said Mills. “But once I felt I could trust Joey, it moved into the realm of the subconscious – I could feel his playing more than actually listen to it.”

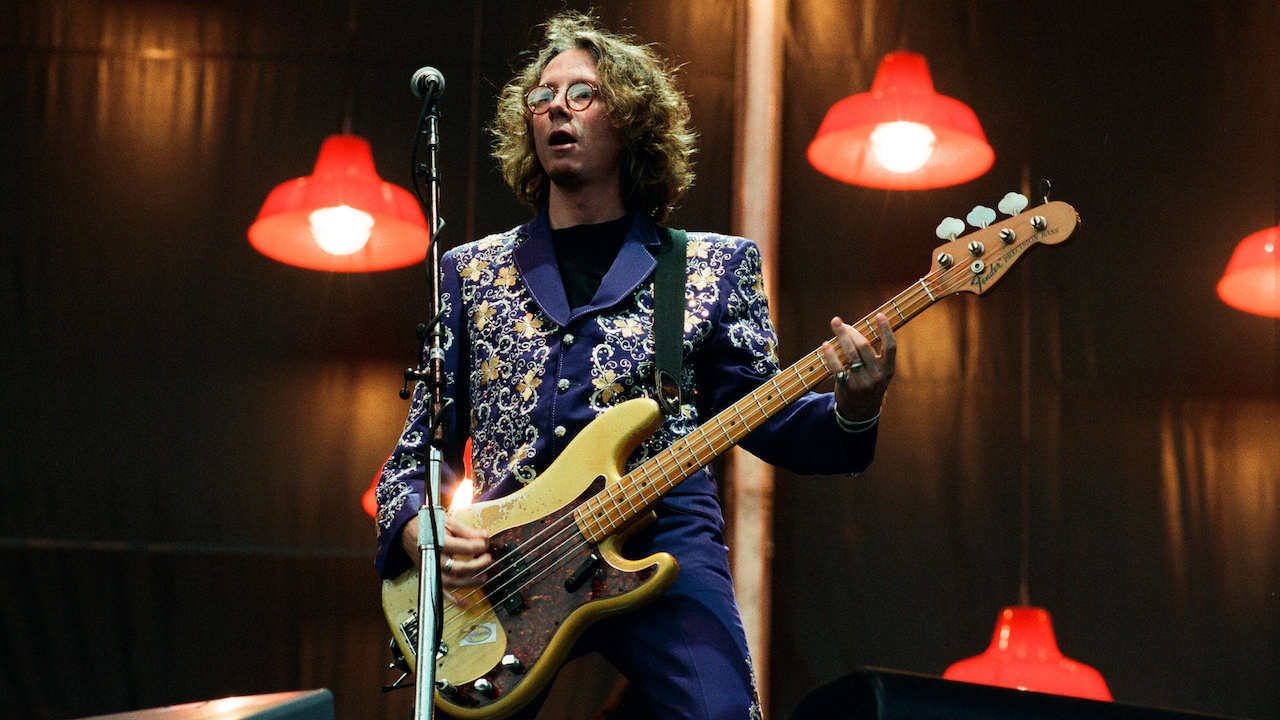

Over R.E.M.'s 31-year career bassist Mike Mills quietly developed a near-cult following with his sublime, ultra-melodic basslines. A master of rock and roll scaler motion, he would string together guitar chords – and apply new ones – with a subtlety absent in most ‘alternative’ rock, a term R.E.M. all but coined.

“Early on I discovered that the bass player decides the chord – not the guitar player. Even all the way back to Sitting Still, Peter plays only two guitar chords per line of the verse, but because I changed the bass note, it sounds like there are three guitar chords. Or Orange Crush where the guitar is so non-specific that if you remove the bassline you could probably take the tune in six different directions on bass, depending on what chords you heard in your head.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The following interview from the Bass Player archives took place in March 1999.

You once mentioned you try to think of John McVie, Paul McCartney or James Jamerson when you're coming up with a bassline.

“That's still my sensibility – but I play a little less than I used to. A lot of making Up was about finding which things were necessary and exercising all the things that weren't, and that includes the bass guitar. There are very few songs where an instrument starts at the beginning and plays all the way through.”

Did you make those decisions as you were recording, or were things dropped out at mixdown?

“Both. We'd listen to what we had, and we were free to run out and play down any ideas we'd get. If it sucked we'd take it off. Sometimes we knew right away it was inappropriate, but a lot of parts were taken out during mixing, too.”

Can a bass player learn what works and what doesn't without the decades of experience you've had?

“I'm tempted to say yes – but in reality it's hard to be self-editing when you're younger. I enjoyed those times rocking hard through the whole song; it’s necessary to get to the place we're at, and I wouldn't want to rush through it. When you're starting out it's fun to play a lot, and part of the fun is coming up with things that are good from the beginning to the end of a song. But eventually you start to repeat yourself if you're not careful. As you get older you realise it's better to pick your spots. I'm not saying one is better than the other – but after you've been doing it for a while, the challenge and excitement often come from getting the killer part that's perfect for one spot and nowhere else, even if that means playing only in the bridge of a song, like on Hope.”

How much experience did you have playing with drummers other than Bill?

“Not much: he and I had been playing together since 1975. I worked with Dave Grohl on the sessions for the Backbeat soundtrack, and I've sat in with countless bands – but I've never done a serious, long-term project with anyone else.”

Would you ever play a show without drums?

“I don't think so. As a fan, I prefer a drummer in a live show, certainly over tapes or a machine. As a player, too – in a live set we just need a drummer. But some of the things Joey does live are not traditional kick/snare/hi-hat beats: he might be playing the kick with his foot and a shaker with his left hand. So even though the line up is traditional the approach is a little different.”

Does that affect your playing?

“Not really. Bill and I were always locked in with each other in a mental sense, but not in a physical sense of playing the exact same thing. Once you're comfortable with a drummer, you don't have to listen; you can concentrate on other things. We knew right away Jerry was good, and once I had faith in him being able to keep the beat, I could concentrate on what I do.”

Do you still strum the strings and mute with your left-hand?

“Sometimes. We don't write as many full-out rock numbers as we used to, but I do that live on Walk Unafraid. It's much more of a rock number live than on the record, and I tend to strum pretty hard.”

When you're writing a new song, do you sit down and compose the bassline?

“I generally just start making noise. A lot of times I won't ask Peter what key he's playing in. Sometimes training can be an albatross; if I know what key a guitar part is in I'll go to a certain places I know work. If you don't know the key you won't have any idea what you're doing, and sometimes you come up with a really good part that's a little out of the norm. I also look for little two- or three-note melodic figures I like, and once something strikes me I flesh it out.”

Peter's abstract style seems conducive to that approach.

“He's always left a lot of room for me. Even when he was doing more arpeggiated stuff he still freed up plenty of space.”

How often do you go back and listen to your old material?

“I don't that often, but when I do I think, ‘Man – those were some pretty good basslines!’ I usually remember how excited I was when I came up with a line, and I recall the excitement of discovering the thing I felt made the song. I like my lines to go pretty much unnoticed – except for that one really good lick that makes the song. But more and more I've tried to take tunes to another place, rather than just laying down a bass part because the song needs one.”

R.E.M. has always been fluid with musical roles, but even more so now.

“When you've been doing it as long as we have, it's fun to step outside traditional boundaries. But we've been doing that since the beginning: Peter played bass on a song on Murmur, and I was playing a lot of piano even then.”

What do you think of Peter's bass playing?

“He's a great bass player. His standard line is that all guitarists want to be bass players and all bassists want to play guitar; it's the secret of music. I love the fact that two people can play the same thing and sound different. Having someone else play the bass creates subtle textures and colors that change the song in a very small way while contributing to the overall sound.”

When you play guitar do you think of Peter's style?

“I try not to, because that would defeat the purpose. For one thing, he uses very heavy guitar strings, which I can't really handle. I could never even begin to play like Peter, so there's no point in trying – although his guitar playing has influenced mine to an extent. It’s more subconscious than conscious.”

Does your bass playing influence the way you approach other instruments?

“It's kind of the other way around. I started playing piano a year or two before I started on bass, and since I never wanted to be a boring root-note-locked-with-the-kick guy I tended to play bass more like a piano player's left-hand. Once you grab the keyboard, your bass playing kind of goes to a different realm. I took two years of piano lessons, which isn't much – but then again I wasn't trying to be a virtuoso. I just wanted to be able to sit down and pick things out.”

Do you have any advice for other multi-instrumentalists?

“All I can say is congratulations! That's one of my favorite things about R.E.M. I'm fortunate to be able to play bass, guitar, piano, trash-can lid, whatever. If you're already a multi-instrumentalist, you probably don't need a lot of advice. Just enjoy yourself – but as long as you have the ability, keep learning.”

How much songwriting do you do?

“We all share that task. I never like to walk by a piano or a guitar without playing it – and when you do that, at least some percentage of the time a song comes out. If I've got something good, I'll work on it until I finish it.”

Do you record demos at home?

“I don’t – but I'm going to start, because over the years I've probably forgotten ten or twelve great songs. I may have written something on a piano, but might not be near a piano again for a week, and by that time I've forgotten the song. That's just one of the occupational hazards. But I've always felt that if a tune isn't good enough to stick in my head, maybe it's best forgotten.”

The band seems to have evolved more over the last three records than during any other period.

“We've learned a lot, and we're also comfortable doing different things. Also, it's a challenge to not repeat ourselves. We keep raising the bar for ourselves, and we want to surprise not only the audience, but ourselves as well.”

Is there a downside to not resting on your laurels?

“Well, you might try something you're not very good at! A lot of people don't like Up because it isn't Automatic for the People, or Green, or whatever else they want it to be. I’m sorry for that, but there isn't much we can do. We have to stay fresh. Even if a band risks overstepping its boundaries, it's much more interesting to see them do that and fall short than make the same record six times in a row. Except the Ramones – if they keep making the same record forever that's fine with me!”

If R.E.M. suddenly become unknown, could you create a successful record from scratch knowing what you know now about the music business?

“If Up had just been released as our first record, I believe it would be flying out of the stores, just because it's so different. But because people have expectations of us, the fact that it's different might actually hurt us. People seem to either love this record or hate it – but I'd rather people hate it than be apathetic.”

Is it realistic for musicians to make only music they believe in?

“Yes, it is. It may cost you financially, but if you don't do what you believe in, the ultimate cost is much greater.”

Art above commerce.

“I prefer to say integrity above commerce. I consider rock music more a craft than an art: the word ‘art’ scares me a little, because it implies pretension. When rock musicians start thinking of themselves as artists it creates a gap between the player and the listener. We've spent many years trying to eliminate that gap; in the old days we'd often end up on the floor and the audience would be onstage. When you get to a certain level that obviously becomes impossible, but we never think we're better than other people. Just because you're a successful musician doesn't make you a better person.”

Do you feel pressured to remain commercially successful, or are you free to move on?

“We feel pretty free. New Adventures in Hi-Fi didn't sell that well, even though I thought it was great. That was liberating, because it proved no matter how hard we work on a record, we can't make people buy it. If we walk out of the studio happy, that's about all we can do.”

Although Mills has gathered about a dozen basses over the years, he usually favors his 1969 Fender Precision, which he bought during the recording of 1992's Automatic for the People. “Mike's pretty much a one bass guy,” R.E.M. tech Mark ‘Microwave’ Mytrowitz told BP. “His strings are Dean Markley Medium Roundwounds, and his picks are large, triangular and Dean Markley Extra Heavies. They're the heaviest picks made, you could crack ice with those things!”

Karl Coryat was Deputy Editor of Bass Player magazine in the 1990s. In the 2000s, he wrote two music books: Guerrilla Home Recording and The Frustrated Songwriter’s Handbook, the latter with Nicholas Dobson. In 1996, he was a two-day champion on the television game show Jeopardy!. He works as a comedian and musician under the pseudonyms Edward (or Eddie) Current.