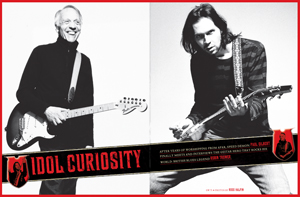

Paul Gilbert & Robin Trower: Idol Curiosity

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Orginally printed in Guitar World, June 2008

After years of worshipping from afar, speed demon Paul Gilbert finally meets and interviews the guitar hero that rocks his world: British blues legend Robin Trower.

It’s not every day that you get to meet your hero, even when you’re something of a hero yourself. Just ask Paul Gilbert.

The super shredder has been a huge fan of British blues guitarist Robin Trower since he was a kid. At the time Gilbert discovered him, in the Eighties, Trower had duly made his mark as a guitarist, first with the band Procol Harum (best known for their hit “A Whiter Shade of Pale”) and afterward with records that he cut with his own trio inspired by the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

“When I was a teenager, I bought three of his records,” says Gilbert. “Bridge of Sighs, Victims of the Fury and Robin Trower Live. To me, these are ‘must listen’ records. The songs are great. The singing by bassist James Dewar is excellent. And the guitar playing is resonant and powerful like a cranked-up Marshall stack, bluesy like a howling hound dog, otherworldly like psychedelic trip through time, and overflowing with the best electric guitar vibrato I have ever heard. Robin is a master of tone and phrasing, and has a deadly arsenal of flash as well. For these reasons, he is my guitar hero.”

So when Gilbert learned Trower was coming to Los Angeles for a performance, he called Guitar World with a special request: Would we like him to interview Trower for a feature in our magazine. As it happened, we were already planning to interview Trower, and so we were only too glad to grant him his wish.

Certainly, Trower made his mark as a potent electric guitarist throughout the Seventies and beyond. In particular, Bridge of Sighs, his 1974 release, was a stunning effort that featured his incendiary Hendrix-inspired playing on cuts like “Too Rolling Stoned,” “Little Bit of Sympathy” and “Day of the Eagle.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As Gilbert notes, Trower’s talent has continued to grow. “His 2003 album, Living Out of Time, is sonic proof that Robin retains all the fire of his classic Seventies releases,” he says. Trower’s newest album is Seven Moons, a collaboration with legendary Cream bassist and vocalist Jack Bruce.

In this unique interview, Gilbert finds out what makes his hero tick and demonstrates that even heroes have their heroes.

PAUL GILBERT Growing up, the records I had of yours were Bridge of Sighs, the live albums and Victims of the Fury. I listened to them over and over. And I especially loved Living Out of Time. It really had a youthful power and energy to it. I really got the feeling that, Wow, Robin Trower is back with that record. But on all those albums, throughout your career, how much rehearsal and preparation have you done before hitting the studio?

ROBIN TROWER With Living out of Time, I think we rehearsed five days before going into the studio. And Seven Moons, the album I just recorded with [legendary Cream bassist] Jack Bruce, we didn’t rehearse at all, but we spent time, he and I, writing songs together, so that’s a kind of rehearsal. We had a good formation in our minds of how those pieces went. All we had to do was find a drummer and then record them.

GILBERT Is that much different than what you were doing in the early

days with the Robin Trower Group [with bassist/vocalist James Dewar

and drummer Reg Isadore]?

TROWER Well, on Bridge of Sighs, for instance, a lot of those songs were played on the road before they were recorded. So there are many different ways you can go at it. But just like when I recorded with Jack Bruce, we wanted it to feel fresh.

GILBERT You played with Jack in BLT [Bruce, drummer Bill Lake and Trower] in the Eighties. That was a very cool record that I enjoyed then. So what inspired you to record with him again on Seven Moons?

TROWER For quite a few years, Jack and I were talking about doing a remix of the stuff we’d done in the Eighties, or repackaging it, trying to bring it more up to date, soundwise. And Jack said, “Why don’t we add a couple of new songs to it?” So we got together and started writing. Before we knew where we were, we had four or five songs and it was obvious that we should do an album.

GILBERT So in your live set, how do you balance this new material with the expectation that you’ll play Robin Trower hits?

TROWER I’m doing all my “must play” stuff—my own stuff. I don’t do anything off Seven Moons. I’m saving that for when I

come out with Jack.

GILBERT Ah, so you’re going to do a tour together?

TROWER Oh yeah. Well, we’re definitely talking about it.

GILBERT One thing that I love about your recordings is that, to my memory, almost every studio recording you’ve done has just one guitar track. You haven’t overdubbed or layered them.

TROWER I like to do it that way.

GILBERT What’s great is it’s in your face. All the nuances are clear, and there’s such personality there.

TROWER See, that’s the thing. The songs, when I write them, will start off with a guitar part. And it has to be a guitar part that I think is an actual part, not just strumming. It has to be a complete arrangement, in other words, and it has to be working as an entity unto itself before I even had an idea of writing a song to it.

GILBERT Do you have a little cassette player to document those ideas before you forget them?

TROWER Exactly, a little cassette player. But you know straightaway if you’ve got a song or not. Within half an hour, you should

pretty much have the shape of the thing. If you’ve got to bash away at it, throw it out. It wasn’t meant to be. From the point of first getting an idea it should be within… okay, I’ll give it an hour. You should have that musical idea narrowed down. ’Cause the ideas should flow naturally, one from the other, until it gets to the end.

GILBERT What if you have one great idea…

TROWER But it won’t go any further?

GILBERT Yeah. Do you have any tricks for getting past that barrier?

TROWER You just gotta try the couple of things that are obvious to

you about where you should go with it. There will only be two or three

things that suit you and one thing that’s great. As I say, if you haven’t

got it in an hour, just don’t bother with it.

GILBERT You don’t have many instrumental tunes. Most of what you do is with a vocalist. So how do you see the art of balancing vocals and guitars together?

TROWER It depends. With some of the songs I wrote with James Dewar, he would put the vocals onto my guitar arrangement. With some of the other songs, I would do the whole thing. So there are many different ways of doing it. And in the end you just know when you’ve got something that works. That’s it really.

GILBERT It sounds like you’ve worked with people who are talented, and when that’s the case you don’t have to put much thought into it.

TROWER Yes, if you’re working with talented people, they know naturally what is good for a song. Like Jack Bruce’s bass playing—he just naturally knows what’s right and what you’ll like.

GILBERT The same is certainly true in your case. Your vibrato, phrasing, tone and musical emotion are incredible.

TROWER Thank you.

GILBERT How do you do this?

TROWER I think, like any gift really, it’s something you’re born with. And obviously, a certain amount of it is emulation of people you’ve heard do it before you. For instance, when I heard my first B.B. King record, in the Sixties, I thought he was playing with a slide. You heard that bend and vibrato sort of thing.

GILBERT So when you first heard B.B. King, you’d already been playing?

TROWER I had been playing for a while, and I was already doing vibrato, but not the bend and the vibrato. That was something new. And you try to emulate that. Or, more accurately, you try to emulate that emotion. I think that’s been my main approach all along. Even though I’ve got guitar heroes, I’ve never tried to work out exactly what they’re doing. I just try to find out what’s behind it, or feel what it is that they’re feeling to make it sound so emotional.

GILBERT So what was it about those blues emotions? I would imagine that the life of an American traditional blues musician might be different from the kind of life you had growing up in the U.K.

TROWER Absolutely. The life they had was more to do with what they were singing about in the lyrics, but the emotion in the music is from somewhere below the conscious level. And that’s something all human beings have in common. [Dimitri] Shostakovich, a Russian composer, wrote very emotional music, as did various other classical composers. Egyptian folk music is very emotional. But what you’re talking about, in terms of adherence to black music in America, is a stylistic thing that enables you to express your own emotions by using a formula, if you like.

GILBERT The vehicle of the blues.

TROWER Yeah.

GILBERT In your playing and that of other blues greats, what makes the playing and the music beautiful is something that’s very difficult to write down in notation. Whereas something like a Bach piano piece can be written down, just because of the way the music is.

TROWER There’s a mathematical side to that kind of music. That’s what you mean, isn’t it?

GILBERT It’s just that the way the notes are bent and milked in the blues, and that whole style of emotion is really hard to put down in traditional notation.

TROWER Those are things that I don’t think you can copy, which is really why there are no great white blues players.

GILBERT Well, there’s you.

TROWER No. I don’t consider myself to be a blues player. I consider myself to be blues influenced. I’m very influenced by it. But blues for me is black American folk music. You can get close by imitating it, but it really does become blues-influenced rock and roll when white guys do it.

GILBERT But I love where you took it!

TROWER Well, when I started writing my own music, I knew I wanted to bring in all my influences. James Brown was a huge influence, and that whole soul thing: Stax Records, Booker T. and Otis Redding. And there’s people like Donny Hathaway. All that fed into my songwriting. But I wanted to stay in contact with the fundamental blues soulfulness. That’s basically what I try to achieve with the guitar: to be soulful. And that doesn’t necessarily mean working in a blues formula.

GILBERT So when you were first learning to play this style, how naturally did it come to you?

TROWER Oh, very naturally. That’s the thing. I always knew that you must not try and play like someone else. I knew that right from the start. You’ve got to find your own way. I was hugely influenced by Hendrix, Albert King and all those guys, but I always knew not to sit down and work out what they were doing, because all you’ll end up with is the notes and not what’s behind those notes, not what set those great guitarists off to play those notes. So go find your own thing. But I always do try to stay in touch with the blues in what I’m doing.

GILBERT When you first started, where was your ear at? Did you already have a big collection of blues records?

TROWER Oh, no, no. When I was 14, the only records I listened to were my brother’s. He was four years older than me, and he was bringing in Elvis Presley, Gene Vincent, Jerry Lee Lewis and Chuck Berry. People like that. That’s what I was brought up on. Scotty Moore [lead guitarist for Elvis Presley] was the first real guitar player who made an impression on me. I knew when I heard Elvis’ records that I wanted to play guitar because of that. Scotty Moore was a big part of Elvis’ sound. Those riffs and his soloing were a big part of it, really. And I said, “That’s it. That right there. That guitar playing. That’s what I want to do.”

GILBERT Do you remember your first steps on the guitar? Did you learn a pentatonic scale? What were the earliest things?

TROWER Chords from a chord book. I just tried to learn chords. It seemed that that’s how music works. It didn’t take me very long.

GILBERT So the guitar came naturally to you. But what took effort?

TROWER I was never a great practicer. I think it all comes naturally. But that’s because I’ve been playing so long, I think. By the time I became a solo artist, I’d already been playing for 14 years. So even though I didn’t practice, I had a lot of experience.

GILBERT Maybe you didn’t practice alone in your bedroom, but you were doing a lot of rehearsing for shows.

TROWER Yeah, I had a huge amount of experience then. And when I started to write my own music, the lead work naturally blossomed out of the music I was writing. All the soloing and lead guitar parts come out of the music. The actual lead solo and stuff—it grows out of each song. It’s an entity unto itself. Why somebody like Albert King is the greatest is because, compositionally, his solos are beautiful melodies. You want soloing to be free. You want it to be something that you’ve just invented in that moment. But at the same time, you want it to be compositionally right.

GILBERT So that you’re not just babbling, you’re telling a story right off the top of your head.

TROWER Absolutely. It’s got to be compositionally right for the song, not just some licks you’ve learned and are overlaying.

GILBERT As you’re improvising, are there certain things you focus on to help your improvising? Are you listening to the drummer?

TROWER No. When I’m improvising long, moody solos, I tend to not hear what I’m playing to. I’m sure it’s there subconsciously.

But I’m so wrapped up in what I’m doing that I’m not consciously hearing what I’m playing to.

GILBERT So in order to do that, you have to be at a point where things that a beginning guitarist would struggle with, like where to put your fingers, are no longer an issue.

TROWER Yeah, that’s right.

GILBERT So that’s the trick to soloing emotionally!

TROWER Well, it is. I’ve got a new piece. I’m thinking of doing an instrumental album next, and one of the things I’ve written is called “The Triumph of Heart Over Mind.” And that, to me, is what you’ve got to achieve. It’s got to be emotions first—getting the head out of the way— because the emotions will put you somewhere you couldn’t think of. That’s the trick really: lose yourself completely and just let it flow.

GILBERT Outside of music, are you a particularly emotional person?

TROWER I think I’m sentimental. A romantic and sentimental, yeah. I don’t know if I’m particularly emotional, because I’m very even-keeled.

GILBERT Do you pick up a guitar and work out pent-up emotions?

TROWER That helps a lot, yeah, that outlet.

GILBERT I haven’t quite been able to take all the things from the brain side of my playing into the heart side yet. They gradually fall into the heart side, but there’s a fair amount of stuff that I’ve still got to think about. When I’m performing live, I can tell the difference, and I like the heart stuff better, so I’m always trying to think of a solution to this. One of my solutions is to imagine

that you [Trower] are at the soundboard, watching the show. And I think, If Robin’s here, I’ve got to discard this noodly stuff and play something that’s meaningful and cool.

TROWER You know what Obi-Wan Kenobi says to Luke Skywalker: “Let go. Use the force.” And that’s what it’s like. You’ve just got to let go. You can’t think about it. You’ve got to assume that your fingers know quite where they are. The conscious part of playing, that’s not really important. It’s the subconscious. You gotta let the subconscious do it. ’Cause it’s all in there.

GILBERT If you were playing a show and could have someone at the soundboard who you feel would inspire your playing, who

would it be?

TROWER Jack Bruce.

GILBERT Reading through some of your older interviews, I was surprised to see you talk about using the middle pickup quite a bit.

Most Strat players tend to flip to one of the outside positions. What’s so appealing to you about the middle?

TROWER It’s got more crunch to it, but it’s clear. It’s clear, but not so keen as the bridge.

GILBERT And I was surprised that you said you keep the volume control around seven. You don’t have it on 10 all the time.

TROWER Well, when I’m playing behind the vocals I’ve got it to seven or eight. And then I’ve got that extra bit for solos. When you’re playing single notes you need more volume. But when you’re playing chords and things, you’ve got to clean it up a little bit.

GILBERT Another thing: do you use the whammy bar?

TROWER Oh yeah. I wouldn’t be without that, definitely. Just for vibratos on chords.

GILBERT But most of your vibrato, I think, comes from your hands.

TROWER Yeah. But for chording, the whammy bar is such a nice thing. Even though the tuning problems are horrendous, I couldn’t

play without one. There’s so much I do with it.

GILBERT So tonight, before you go onstage, do you have some way to prepare? Do you think, This is gonna be the best night I’m ever gonna play in my whole life?

TROWER No, because it isn’t. That’s down the road apiece.

Since 1980, Guitar World has brought guitarists the best in-depth interviews with great players, along with exclusive lessons, informative gear reviews and insightful columns that help guitarists grow and excel on their instrument. Whether you want to learn the techniques employed by your guitar heroes, read about their latest projects or simply need to know which guitar is the right one to buy, Guitar World is your guide.