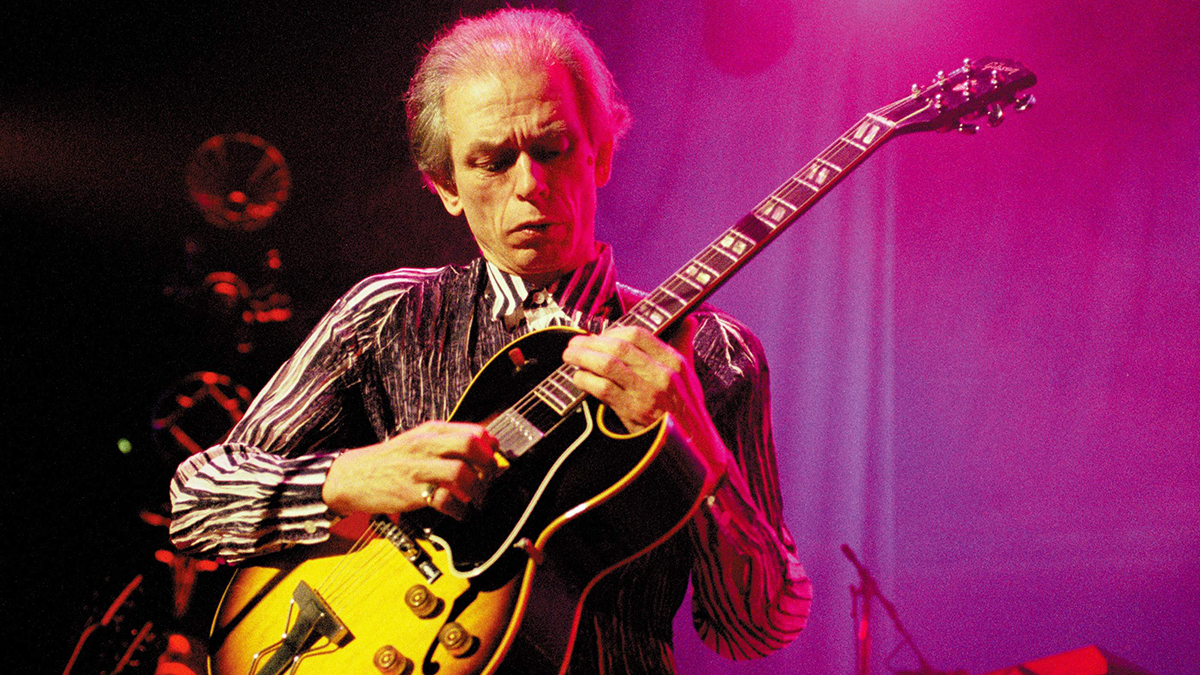

Producer Profile: Alain Johannes

Getting down to the basics with the king of '90s alt-rock

Whether for his frenzied fretting and boisterous bass work in bands like Eleven, Queens Of The Stone Age and Them Crooked Vultures, or for his genre-defining wizardry behind the console as a producer and engineer, there are plenty of reasons why Alain Johannes is such a revered name in rock, grunge, punk, and pretty much any genre of guitar music that made it through the ‘90s. With his latest solo album Hum doing the rounds, we caught up with Johannes to glean some of his signature bright, energetic wisdom.

When you’re making your own music, do you follow the same formulas you would as a producer with any other band, or do you need to approach it from a different perspective?

I approach every project in the way that I feel is most natural – my resonance and my empathy and my desire to connect to the project as a part of it, whether as an assistant, a guide or a team player, or a family member to the music – which means that every time I work on a new record, it’s a different set of things that happen. I don’t have one definitive way of doing it.

First of all, I need to resonate with what the artist I’m producing wants to achieve, and figure out what my role is in helping them do that. Sometimes it’s intensive, and sometimes it’s very mild. It might just be that I need to make a happy environment for them to feel creative in, and make sure that creativity gets documented and recorded properly. Sometimes they want me to get in there and contribute to the writing and the arrangement and all of that stuff.

When it comes to my own stuff, I think I’ve prepared my entire life by loving and learning other instruments. I’ve spent years collecting equipment, and I’ve got my setup to a very efficient point – I can just go into the room and there’s five or six different microphones ready in different positions, and depending on what instrument I’m using, I’ll choose what microphone to use. And all the microphones and the instruments and everything – the percussion and my horns, my 60-plus stringed instruments and all the exotic instruments – they’re all basically living in this space, just ready to be grabbed.

I love flowing with whatever the music dictates, or whatever my instincts are telling me to do. For example, on a couple of tunes I used a banjo, because I’m yet to purchase a hurdy-gurdy but I wanted that kind of medieval, pagan feeling. And I totally knew that if I tuned the banjo in roots and fifths and played it with a bow, with that midrange that it has, and get a couple strings droning in the same note, I would get that feeling. And I just love that kind of spontaneous, improvisational kind of approach – it happens really quickly and there’s very little thinking to it.

Do you it difficult to be objective when you’re in that position?

I don’t, because for some reason I’ve got this view towards my music that it’s something that already exists in the ether – I’m just receiving a transmission from the universe that I’m supposed to decode through my particular filters. I don’t really look at it like, “Oh, this is mine, I did this” – I mean obviously, y’know, it says ‘written and performed by Alain Johannes’ on the sticker, but it’s not mine to claim – the music is there, and I’m just here to help it come into existence. It feels natural to me that way, and it helps me be able to look at it afterwards and go, “Yeah, this is music!” It just happens to be mine, y’know?

I don’t want to attach an ego to it – whether it’s good or not, or whatever – I’m really trying to just document the feeling I have and my state of being in a particular time.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The first takes are always some of my favourites. The closest I can get to the exact moment song appears is usually the best, because it has the most energy to me – it has the particular kind of that energy that I like, which I listen for in other music as well. And y’know, I know full well that if I start to obsess over a tone or a guitar solo, and then I might do ten takes of it before I realise that the first one was the one that felt the best for the song. Learning that throughout the years was crucial – especially when I was younger, because y’know, when you’re green to it all, you think that there has to be a process and it has to be arduous, and you have to torture yourself, and only through blood, sweat and tears can you get amazing results. But that couldn’t be less true.

I’ll tell you what though, starting the record is always the hardest part. I can’t will that to happen – I can never convince myself to just sit down and go, “Alright, I’m going to start making music now,” because if I’m going to come up with a good idea, then it’s going to happen at whatever spontaneous moment it’s going to happen in, y’know? And to put a timeframe on making an album just doesn’t make sense. A good album might take four days to make, like Spark, or 14, like Fragments – or other records I’ve been a part of where it took ten months or whatever.

What is it about the way music was made in the ‘90s that makes it so beloved amongst people today?

My first recordings were in the ‘80s, straight out of high school, and so that time period was particularly exciting for me. But my approach was just what everybody else was doing – and everybody was doing it that way. You can spot an ‘80s-sounding song a mile away. And I think the way things changed in the ‘90s was a reaction to that – and MTV, and a lot of the things that happened in the cultural shift back then. And also, the energy in Seattle at the time – there was just this amazing pool of talent that happened to be there for some reason. I don’t know if it was the environment that fostered it – a little darker and colder, more melancholy, and just more interesting than what came from a lot of the happier pop or hair metal or whatever else was happening at the time.

I think the way that a lot of those records were made – especially in some of the earlier studios that still had the analogue technology, before everyone went digital – they made them more timeless sounding. It’s like jeans, a t-shirt, a leather jacket and a pair of boots: there aren’t too many distinctive features about that outfit, but it’s always cool – that kind of stuff works almost any time, anywhere – you can wear that and just know you look stylish. And when you record music without too many effects and you’re just capturing the energy, it tends to have a more timeless kind of sound. A lot of those recordings in the ‘90s were very full-sounding and very powerful, but they didn’t have a lot of fat around the edges.

I mean sonically, y’know, you can’t really pigeonhole it – it’s more the feeling of the music that you look at and say, “Oh, that’s from the ‘90s.” There was just something in the air at that point in time; especially in Seattle. The movement and the name ‘grunge’ was ascribed to it after the fact, but it just happened to be one of those moments and places.

What’s the biggest lesson you’ve learned about making music?

I think this constant surge towards autonomy is so overdue. Music used to be so prohibitive, y’know? You could rehearse and do demos and stuff, but to actually go and make a master recording, you had to hire a studio and pay for engineers, producers, maybe session musicians… So pretty early on, Natasha [Shneider] and I started keeping some recording gear around – enough to get things going that we could make good recordings on our own. And I think the key was having our own studio when Eleven was born, thanks to Chris Cornell inviting the president of A&M over, him liking our music and giving us a record deal, and then letting us use the budget for the album to buy the gear that would become the studio in our house.

Ellie Robinson is an Australian writer, editor and dog enthusiast with a keen ear for pop-rock and a keen tongue for actual Pop Rocks. Her bylines include music rag staples like NME, BLUNT, Mixdown and, of course, Australian Guitar (where she also serves as Editor-at-Large), but also less expected fare like TV Soap and Snowboarding Australia. Her go-to guitar is a Fender Player Tele, which, controversially, she only picked up after she'd joined the team at Australian Guitar. Before then, Ellie was a keyboardist – thankfully, the AG crew helped her see the light…