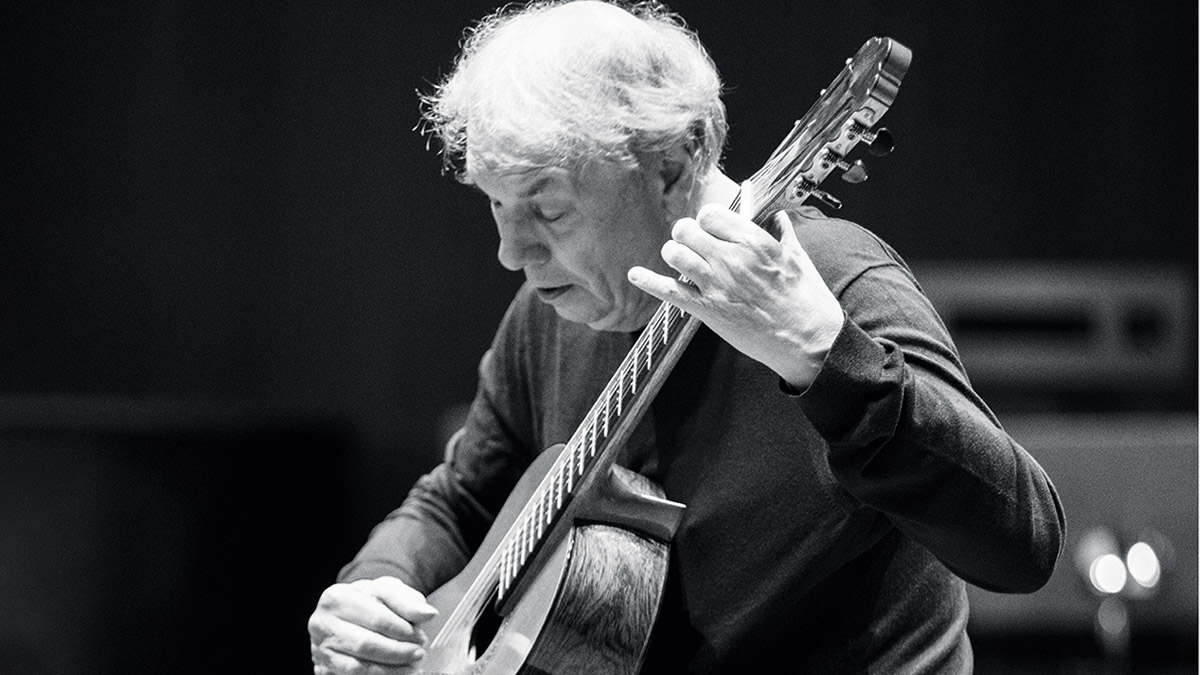

“Guitars adapt to whoever is playing them. I can play somebody else’s guitar for two weeks and it will change according to how I play it”: Ralph Towner on the sensitivity of the six-string – and why he doesn't use an amp on stage

The latest album from jazz guitarist and composer Ralph Towner is a typically enchanting work, complete with beautiful playing on new pieces and jazz standards

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Apart from a solo career that began back in the early 1970s, nylon-string guitarist Ralph Towner has contributed to recordings from a wide range of artists, including Bill Bruford, Robben Ford and Weather Report.

He also has the distinction of having had two craters on the moon named after his compositions, by the Apollo 15 astronauts. He’s a multi-instrumentalist, having begun his musical journey playing brass instruments before teaching himself to play piano, but it was to be the guitar that formed the main focus of his music.

His latest album, At First Light, finds him playing solo nylon-string guitar on a collection of new pieces, plus jazz standards by Hoagy Carmichael and Jule Styne as well as a reading of the traditional song, Danny Boy.

You started off as a pianist, didn’t you?

“Yeah, I had heard the Bill Evans trio and I wanted to know how it felt to play the piano like that. He was my model for the first few years, so I’m basically self-taught in terms of being a jazz pianist.

“Before that I played brass instruments from the time I was seven or eight years old, and played in bands, little concert bands, or whatever. But as far as the piano is concerned, my mother was a piano teacher so I was always immersed in piano, but more with hearing my mother’s piano lessons. I was so stubborn, I wouldn’t take piano lessons from her…

“I got really involved in my second year at university when I was introduced to the Bill Evans trio, but I played a lot of jazz and Dixieland on the trumpet. I started hearing music from my older brothers’ record collections and was introduced to everything from Duke Ellington and Spike Jones to classical music, which I ended up studying as a composer.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

What made you change from piano to guitar?

“I don’t know, I just heard it. I was deeply involved in learning the piano, but I was struck by the guitar – how it sounded. I heard a student playing a classical piece, probably Bach.

“I can’t remember the piece, but it was just the beauty of the instrument and the resemblance to a keyboard. It didn’t enter my mind that this was going to be my major instrument because I could survive quite well in New York on the piano.

“I had just started to play with bands and do gigs and I gradually noticed that the players I played with were better and better and I started playing with well-known players. But when I heard the guitar it struck me. I don’t know why I was so drawn to it.

“I finished college and I had nothing holding me back. I didn’t have parents who said, ‘Oh, go get a real job,’ or something like that. I’d put a lot of time into getting my diploma as a classical composer and, on the side, developing jazz piano. I asked around, ‘Where’s a great guitar teacher?’ And one of the professors said, ‘Oh, Karl Scheit in Vienna is a great teacher,’ and I almost said, ‘Well, where’s Vienna?’ [Laughs]

“So I wrote a letter to the music academy where he taught and somehow they allowed me to audition. It was kind of obvious that I was a musician, so I was accepted. I somehow managed to get there with very little money, but things didn’t cost much in Europe, really, as far as studying and education. Wonderful system, actually. So I managed to get to Vienna and then I locked myself in a tiny little room and practiced and studied for seven days a week.”

What’s your approach when you’re writing for solo guitar?

“I’ve evolved, of course, over the years. I’m still a bit of a songwriter, although I’ve written some orchestral music and stuff, but I still like to play an instrument, either the piano or the guitar. Just improvise a little bit until I stumble across an idea, which is either a chord progression or an interval.

“But you have to be able to discern what is an actual potential piece or just a nice collection of sounds. So when you find something that’s a real idea – when I find it anyway – I can instantly identify it, hear it telescoping into a full piece. And so it works its way through.

I still like to play an instrument, either the piano or the guitar. Just improvise a little bit until I stumble across an idea, which is either a chord progression or an interval

“I think it’s a little Darwinian because it’s the same species all the way. If it’s using a musical language that is set forward in the first few notes, you have to let it go where it wants to go, you can’t force it. It’s really interesting, this initial catalyst between two things.

“You’re able to develop the story it’s telling, music being its own language, and basically evolve that until it’s accomplished something, in terms of having developed and revealed and pulled some surprises. It’s all very emotional, also. I’m very emotional about music and I feel like it’s possible to [express all the emotions] in music.”

On the new album you’ve included a couple of standards, which you’ve said was a very deliberate choice – that you wanted to have arrangements of standards on the album as well as original pieces.

“Yeah, I mean, I played standards on the piano for years. I learned a lot of them from my brother’s record collection. And then my mother would play the piano and would buy whole books of standards, so I learned how they functioned.

“But I was able to improvise from the first time I picked up an instrument – play counter melodies – and so I had a knack for it to start with. They’re so much a part of my life and some of them are wonderful.

“Bill Evans was great at finding beautiful standards and making them into jazz standards. I was teaching myself how to do that as a result of hearing him. And the way they’re originally written, I mean, the art of writing these songs that, even without lyrics, tell the story in a musical way. And so I always want to include some of those because they’re written so well, and then put my own touches on them. I think it gives a little bit of variety to the record.”

What is the make of nylon-string guitar that you play throughout At First Light?

“The guitar I’m using now – I’ve been using it for a few years – is made by an Australian maker, Jim Redgate. Previous to that I played a lot of Jeffrey Elliott’s classical guitars. The first really good classical guitar that I bought was a RamÍrez, an older one.

“Unfortunately, I only had it for less than a year and it got stolen in New York City. That was it, you know, it was gone. But at least I had experienced what it was like to own a beautiful instrument that I really liked to play. But I discovered these other instrument makers and I’m very happy with the Australian ones lately. But most of my recordings are done with the Jeffrey Elliott guitars.”

Do you have any special requirements from the makers of your classical guitars?

“Oh, yeah. My preference is not to have any frequencies dominate or outweigh the highs and the lows and the mids, so you can control the whole thing. Sometimes certain notes will jump out, but a well-made guitar will be really even, if you can find one like that. The quality of the sound, of course, is pretty subjective. But, as I say, I like it very even, in terms of the dynamics that it has.

“Guitars adapt to whoever is playing them. They become very personal to the guitarist over a period of time. I can even play somebody else’s guitar for two weeks and it will change according to how I play it. I mean, it’s interesting. That’s a nice thing about a guitar. I think all instruments might do that, but the guitar is particularly sensitive.”

You don’t use an amplifier on stage, preferring to mic up your guitar instead. What led you to make this decision?

“The reason, and it’s kind of a musical one, is that as a classical guitarist you spend most of your life on an instrument trying to develop complete control and the illusion of tones sustaining even longer than they actually do, in terms of how loud you play each string, and how long it sustains.

“But the thing about amplification, although it’s improved so much over the years, is that it’s always sustaining beyond the dynamics of [what you’re playing]. You’re trying to hide certain notes and voices behind others, it gets to be that subtle. And the electric thing amplifies it too much, almost, so everything is sounding and it doesn’t really sound like your sound, although it has improved.

“I spent all this time learning how to control the subtle things, and with the amplification you end up hearing the pitches and a little bit of the articulation, but you don’t hear the dynamics quite as clearly between the individual strings. It depends on the player, but with amplification it comes out sounding more electric, which, as I say, defeats all your studies.

“But I play quite loudly and the microphones I use are very good – and you have to have a good tone when you’re pushing it through a microphone. It’s kind of telling the truth when you get it out in the audience, although it still has to go through speakers.

With the amplification you end up hearing the pitches and a little bit of the articulation, but you don’t hear the dynamics quite as clearly

“So it’s tricky doing a mix for a concert on a sound system, but I believe in the sound systems anyway. It’s kind of amplified that way. But I use two really good mics that I choose between.

“One’s a double ribbon mic I first started using in England. It’s a Beyer[dynamic] M 160 double ribbon mic and then the other one is a Schoeps, a very nice mic that doesn’t feed back and is used for orchestral recording. Great with the guitar, too, but it’s very narrow – you know, it’s placed in the orchestra and picks up the instrument you want it to without getting everything else.”

- At First Light is out now via ECM Records.

With over 30 years’ experience writing for guitar magazines, including at one time occupying the role of editor for Guitarist and Guitar Techniques, David is also the best-selling author of a number of guitar books for Sanctuary Publishing, Music Sales, Mel Bay and Hal Leonard. As a player he has performed with blues sax legend Dick Heckstall-Smith, played rock ’n’ roll in Marty Wilde’s band, duetted with Martin Taylor and taken part in charity gigs backing Gary Moore, Bernie Marsden and Robbie McIntosh, among others. An avid composer of acoustic guitar instrumentals, he has released two acclaimed albums, Nocturnal and Arboretum.