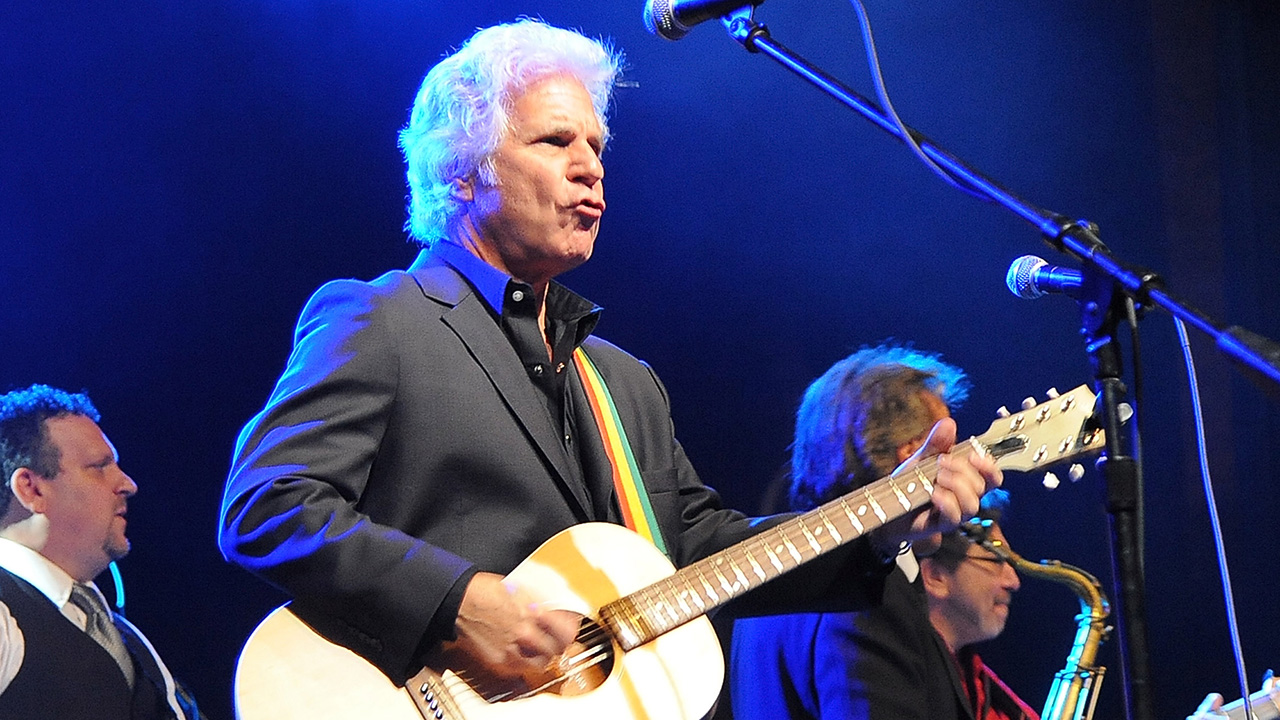

“I don’t know what it is about my Tele, but it’s special. Roy Buchanan tried it and wanted to buy it! I said, ‘No way in hell I’m giving that up’”: Russell Javors on his wild ride with Billy Joel – and his friendship with Les Paul after he was let go

Billy Joel’s former right-hand man had given up on music until he accidentally reconnected with his old colleagues – so what does he think of the suggestion that their Lords of 52nd Street group are better than Joel’s current band?

If you’re from Long Island, New York, three things remain constant: the pizza, the bagels, and the music of Billy Joel. Fans of the Piano Man know him for hits like My Life, Big Shot and Allentown, which fused doo-wop, rock, R&B and soul – a mix that defined a generation of listeners, especially from Long Island.

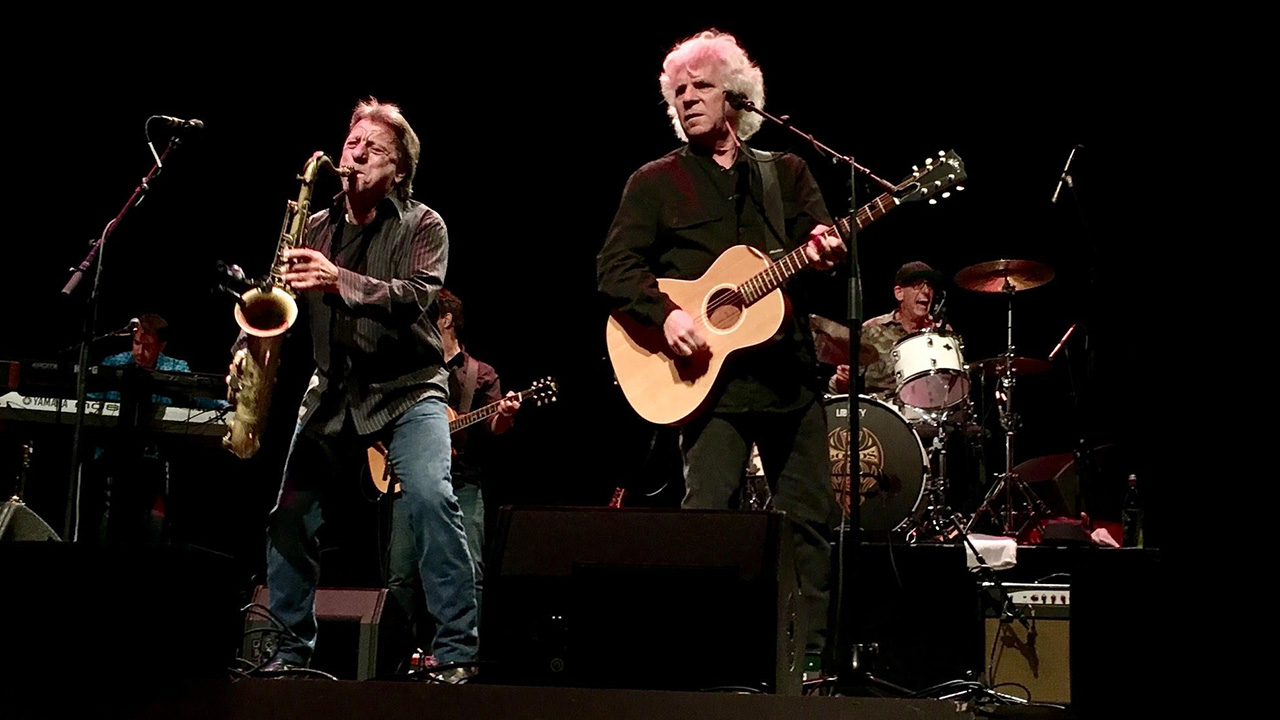

Joel might have been the voice, but without his band of New York musicians – Richie Cannata (saxophone), Doug Stegmeyer (bass), Liberty DeVitto (drums) and Russell Javors (guitar) – his music would be flavorless.

“My perspective was song-oriented,” Javors says. “But the fact that we were guys who grew up together and had a lot of fun together kept the music loose.”

While Javors’ approach provided texture and guidance for Joel’s tracks, he contributed some memorably rocking licks to You May Be Right, from 1980’s Glass Houses.

He stuck with Joel from 1976 to 1989, recording six studio albums and two live discs; the latter of which, 1987’s KOHLIEPT, came about under tense conditions in the Soviet Union. Not long after, Joel cleaned house, leading Javors to walk away from music – and winding up in the toy business – before shifting to entertainment relations with Gibson.

But that changed in 2014, when Javors, Cannata, Stegmeyer and DeVitto were inducted into the Long Island Music Hall of Fame. Soon after, they formed The Lords of 52nd Street, and continue to perform their era of Joel’s music to great success.

Some even say they’re better than Joel’s current band. “I don’t know about that,” Javors says, “but it was an interesting bunch of guys we had. We were like family, which differs from what’s out there now.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“We had a take-no-prisoners attitude, and watching Billy become a superstar was wild. It reached a point where the arenas were like intimate living rooms. Watching that was special. I’m just proud to have been a part of it.”

Your Billy Joel odyssey began when you met Liberty DeVitto and formed Topper. How did that go down?

“There was a local club in Plainview, Long Island, that I used to go to after school. That club had two house bands and one was called The Hassles, which featured Billy Joel before he became Billy Joel. The other band was The New Rock Workshop, and I got friendly with those guys; I was maybe 16.

That Tele was and is the best-sounding Tele I’ve ever played… Roy Buchanan wanted to buy it! I said, ‘No way in hell I’m giving that up’

“Liberty was the drummer, and we got to be friends. He was a little older than me, and I bugged him until we started hanging out more. After that, we found Doug Stegmeyer on bass and started writing songs. We began to develop natural chemistry from there.”

What did those songs look like from a guitar perspective?

“I play guitar, but I never considered myself a guitar player. I thought of myself as an aspiring songwriter, you know? I loved the guitar, but it was just the vehicle I chose. I was very blessed to play with such talented musicians. What we played didn’t matter; we started playing bars and clubs, and the original material manifested naturally.”

Billy’s classic band didn’t come together until his fourth album, Turnstiles, in 1976. How did you enter the picture?

“Billy had made a few records with different people and he was recording with guys from Elton John’s band. But he got to a point where he wanted to form a band with authentic New York and Long Island guys.

“Doug was the first guy who got called because Billy needed a bassist. Billy came to depend on him quickly and trusted him, so when he needed a drummer, Doug immediately said, ‘Oh, you’ve got to call Liberty,’ which he did.

“Once Billy had a real hard-hitting New York drummer in there, and he had Doug, he wanted to round the lineup out with another guitarist. Once again, Doug said, ‘I’ve got a guy who would be right up your alley,’ which was me. It worked because we all idolized The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, and I brought a focus to the guitars that was not about solos but the song.”

From there onward, what did your studio rig look like?

“There weren’t a whole lotta bells and whistles. I had two Teles. The first one was from ’68, my backup, and my main one was from ’70. I still have both. That ’70 Tele is special, and I added a switch between the volume and tone knobs that lets me get an out-of-phase sound. You can hear me use it on It’s Still Rock and Roll to Me.

“As for amps, I initially used a Roland JC-120 Jazz Chorus because I loved the clean sound I got. I also had a ’65 Fender Super Reverb that I used a lot on the ’70s and early ’80s Billy records.”

Goodnight Saigon was important to me… Billy said, ‘I’d like this to unfold like a picture in your mind of the barracks, troops, and all this stuff happening around you’

Was your touring rig essentially the same?

“It had to be because I liked my sound to be consistent. And that Tele was and is the best-sounding Tele I’ve ever played. I don’t know what it is about it, but it’s special. Roy Buchanan heard me playing it, tried it, and wanted to buy it! I said, ‘No way in hell I’m giving that up.’ I beat the hell outta that Tele.

“That aside, the only live change was that I mainly used the Super Reverb over the Roland, and I’d add a little distortion or chorus here and there.”

Though you were known as Billy’s rhythm guitarist, you played the famous lick on You May Be Right.

“I never considered myself a lead guitarist, so it’s funny that the most famous Billy lick was me! I did that with my ’70 Tele and an old Ampeg Jet from the ‘60s. It was very in-your-face sounding, and I just loved it. But I didn’t put much thought into it; I just let it rip, and it’s the one that people remember.”

You were also integral to recording one of Billy’s most poignant tracks, Goodnight Saigon.

“I almost got drafted into Vietnam, but I didn’t go because I had asthma, so Goodnight Saigon was important to me. We were working on that song at soundcheck, and Billy said, ‘I’d like this to unfold like a picture in your mind of the barracks, troops, and all this stuff happening around you.’

“I went into an isolation room, closed my eyes, listened to the lyrics, and let my guitar unfold through this mesmerizing chord chart. Billy liked it, and while we were recording, I flubbed the chords but slid past that and thought, ‘Man, I hope I didn’t just ruin this amazing take,’ but at the end, Billy goes, ‘I liked what you did there – let's keep it.’ It was a happy mistake.”

What are your memories of playing behind the Iron Curtain in 1987?

“It was special. I had my wife and son with me, which was a culture shock. Our type of music was inaccessible to them, and we needed translators to communicate with everyone involved.

“Honestly, even though Billy was so famous, I’m not sure they knew who we were as they’d been barred from rock music due to being a communist country. But they opened their arms and hearts to us. They showed us so much kindness, and we gave it our all to put on a special show for them.”

I got to be good friends with Les Paul; he and I would talk for hours… I’ll cherish those conversations forever

Considering they’d been stifled, what was the audience like compared to the American audiences you were used to?

“When we got on stage, all these political party people were in the seats, and they were reticent because they didn’t know us. The first couple of songs were super loud for them – these people were covering their ears and looking disoriented.

“All of us on stage were like, ‘Oh boy, this is a nightmare.’ But once those political people left, the kids took their seats, and the whole show heated up. It became like a regular concert.

“If you watch the video back, when we’re doing Goodnight Saigon, I’m sitting at the edge of the stage with my guitar, laughing. It’s this serious song, but there I am, smiling and laughing – because the kids were trying to pull my shoes off! I have ticklish feet, so that’s what happened there.”

After such an emotional high, it must have been difficult to leave Billy’s band.

“I had a feeling it was coming. But was it difficult? Yeah, it was. I wish it hadn’t ended, but I’d been through a lot of stuff in my life and I was very lucky to have a great support system at home. I don’t go there in terms of the background stuff, but I knew it was time, and I wasn’t shocked.”

Why did you leave the music business after that?

“I had played with the same guys since I was a kid and I didn’t want to be in another band. So I reinvented myself – I went into the toy business, did well, and I worked for a large Chinese company.

“Through that, I landed a gig with Gibson’s Entertainment Relations Program and oversaw Hong Kong, Shanghai, Beijing, Singapore, Tokyo and Mumbai. I got to be good friends with Les Paul; he and I would talk for hours about our mutual love of toys, and about inventing toys together. I’ll cherish those conversations forever.”

Was your induction into the Long Island Music Hall of Fame in 2014 what reconnected you with your old bandmates?

“Yes. We didn’t expect it, but we got voted in and that’s when we got back together. I hadn’t seen them in ages, let alone played live. But when we got back together, the natural thing was for us to play, and people went nuts.

“That’s where the Lords of 52nd Street came from; it wasn’t planned. After Russia and leaving Billy, I frankly didn’t think anybody cared about the rest of the band anymore, but to my surprise, and as the success of the Lords shows, I was wrong!”

We had chemistry before Billy and it’s there still. It’s not about how good you can play; it’s about perspective

Many longtime fans of Billy’s feel he made a mistake letting you go.

“I can appreciate that. But I don’t want to live in the past. I won’t pretend I wasn’t disappointed when it was over, but how I look at it now is that every good opportunity springboarded off that thing happening.

“When you’re a part of a machine like that, things can find you, so I’m thankful. If not for that experience, I wouldn’t have had the interesting life that I’ve had.”

How do you view your impact on Billy’s music?

“I’m not a traditional guitarist and was never a shredder. But my perspective found its way into the music. I can’t read music and I’m no session player, but magic happens when it comes to getting together with these guys.

“We had chemistry before Billy and it’s there still. It’s not about how good you can play; it’s about perspective. I added character and played in a way that was impactful and memorable. That’s what I was best at.

“Let me put it this way: Liberty stayed with Billy long after I left, and he always tells me, ‘The emotion was gone after you left.’ And then he says, ‘I don’t know what the fuck you do, but it certainly sounds worse when you don’t do it.’”

- Lords of 52nd Street play select shows i 2024 – see Lordsof52ndSt.com for full dates.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.