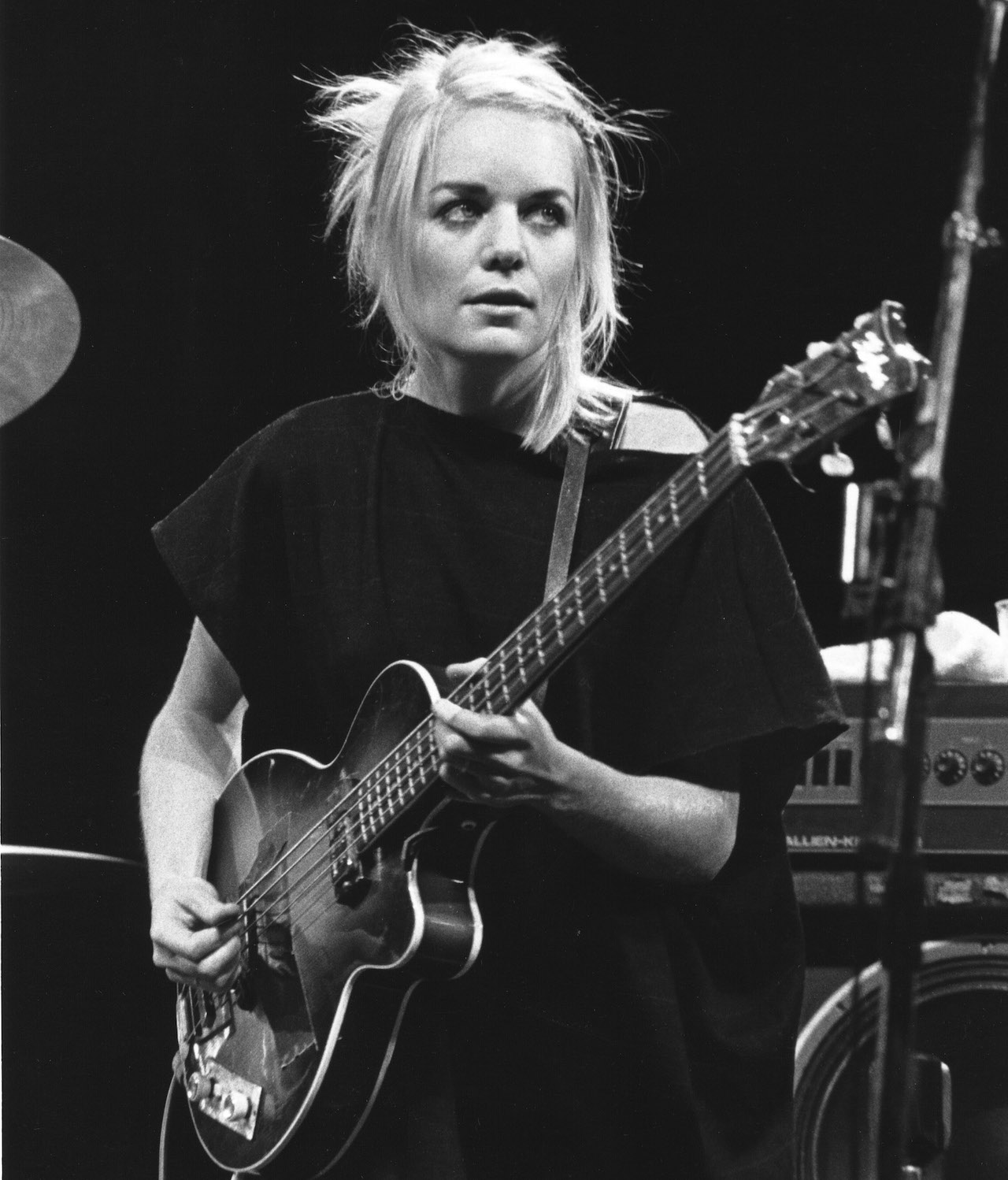

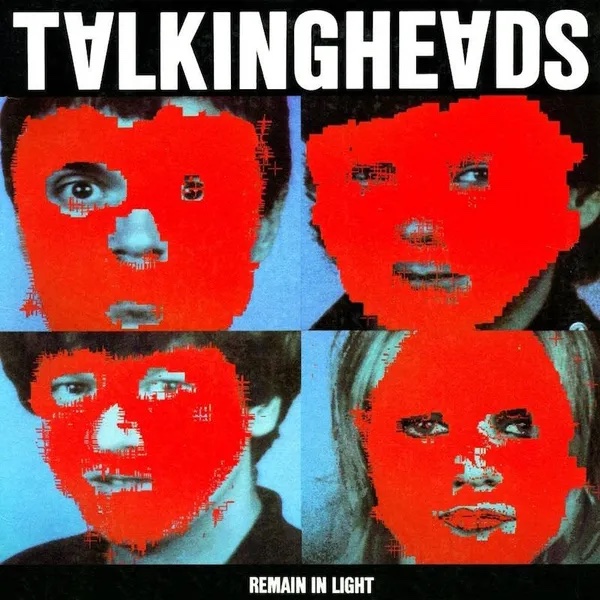

"Without Tina Weymouth, Talking Heads would have been just another band": a celebration of Remain in Light

Released on 8 October 1980, Talking Heads’ Remain in Light is a paranoid funky masterpiece, thanks in no small part to Tina Weymouth’s sinuous basslines

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“I had played guitar,” says Tina Weymouth, “so we all thought, ‘How hard can this be? There’s only four strings’. That’s how little any of us knew about the instrument.”

There’s only four strings. Tina Weymouth started off like many of us – switching from guitar to bass guitar, seduced by the idea that fewer strings would make it easier – and along the way she helped create some of the most interesting basslines of the new wave era. Not bad for someone dragged into bass playing by her boyfriend (later husband), drummer Chris Frantz, and only given one brief lesson, by singer and guitarist David Byrne.

“David gave me a lesson in 12-bar blues and the basic I-IV-V chord progressions, including a guitar lesson in playing [Little Richard’s] Slippin’ And A-Slidin’,” she told me when I interviewed her in 1998 for Bassist magazine. “Now I had to learn to hear those patterns in David’s new style cacophony. That half hour was the only lesson I had: everything else came from observing and listening in rehearsal and in the clubs.

“I should say,” she said, “I don’t recommend this as a way of learning bass.”

Weymouth found herself a Fender Precision (“Somebody thought that – being a ‘petite’ person – I should play one of the small-body Gibsons, but I didn't enjoy the sound or feel of the short-scale necks. Finally, I chose a Fender Precision made in 1963. I liked it right away. It cost $250, five times my weekly pay”) and she was off to the races.

The history of Talking Heads is littered with inter-band feuds and bitterness. Byrne made Weymouth audition not once, but three times and from the very start there were arguments over songwriting credits: the only hit from 1979’s Fear of Music was Life During Wartime, a track that began life as a jam between Frantz and Weymouth, but was originally credited to Byrne alone (something that has subsequently been rectified).

In his 2020 biography, Remain In Love, Chris Frantz revealed that Byrne wanted to fire Weymouth shortly before their first album, in frustration at what he saw as her lack of progress on the bass – at that point, Weymouth had only been playing for a year.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Tina had not played rock and roll before Talking Heads,” Frantz wrote, “and did not have a repertoire of standard blues and rock bass licks in her musical vocabulary. Her approach was more classical. To this day, Tina never ever plays the predictable thing. She invents every part anew — this was one reason Talking Heads sounded so unique.”

For their fourth album, Remain In Light, the blues structures that Byrne had taught her had long gone out of the window.

“David always said we weren’t blues-based,” said Weymouth, “but then played classic triads and classic three-chord progressions. It took until Remain In Light that we narrowed it down to just two chords on every song. Chris didn’t play a single drum fill on that record either. David could be a very melodic singer when he wanted to be and Chris’s drumming was very musicial, highly soulful.”

Inspired by the Afrobeat of Fela Kuti and the methods Byrne had used on the album he had made with Brian Eno, My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts, for Remain In Light, the band and Eno – and occasionally guests like Adrian Belew and singer Robert Palmer, who ended up on the international hit Once In A Lifetime – jammed in the studio.

“We were listening to African pop music,” Byrne told the Library of Congress in 2017, “like Fela Kuti and King Sunny Adé, and some field recordings. But we didn’t set out to imitate those. We deconstructed everything as we began to use the process described above, and then as the music evolved, we began to realize we were in effect reinventing the wheel.

“Our process led us to something with some affinity to Afro-funk, but we got there the long way round, and of course our version sounded slightly off. We didn’t get it quite right, but in missing, we ended up with something new.”

They did. Lyrically paranoid, claustrophobic and anxious, the music of Remain In Light is frequently jubilant and celebratory, and the tension between the two created something genuinely original. Talking Heads could seem arty and cerebral but the music was joyful, daft and trancey.

"For serious or twisted song subjects, I enjoyed juxtaposing rather humorous parts and vice versa," said Tina. "The spikier David played, the more I attempted to make my parts as sinuous and funky as possible. Our parts were equally about contrast as they were about blending."

And this time there was no question about who had written the songs: the band jammed them in the studio, sometimes swapping instruments, hitting on an idea and playing it over and over like “human samplers”. All received equal credit for the music.

The bass parts on Remain In Light, Weymouth told Tony Bacon, were occasionally built out of two or three parts that could have been played by any member of the band. “What had happened, on Remain In Light, we were all playing different instruments, and switching round, and occasionally a bass part would be built out of two, sometimes even three different individuals. The Great Curve, I believe, was one [written like that] on Remain In Light.”

The sound was so dense, that when they toured it, they brought in extra musicians, including bassist Busta Jones, previously of Chris Spedding's band Sharks. "Well, when we added the extra five pieces after Remain In Light, the whole thing changed." she told Tony Bacon. "In fact, even while we were doing Remain In Light, the whole thing changed because, by that time, it became important that what I played was exceptionally minimal, in order to leave plenty of room for whatever else was going to happen."

“In my own playing,” she told me, “I was trying to pay attention to both melody and rhythm as a means to tie together the drums and David’s extremely bright, no mid-range guitar and vocals. With the addition of Jerry Harrison [Harrison joined in 1976, after their first single] and, finally, the big band, I would go for the deeper tones of reggae. I would need to get out of the middle frequencies to leave room for more players, more layers.

“It came very naturally, organically. It was a sort of deconstructive minimalism: playing well-constructed, simple parts with perfect time and a whole lot of feeling, avoiding flabby bombast. Originality was crucial too. To create new sensations it was a matter of slamming divergent elements and song structures together to see if something good would happen.”

Remain In Light broke the top 20 in the US, and the single Once In A Lifetime went to no.14 in the UK. In 2017 it was considered to be “culturally, historically, or artistically significant” by the Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Recording Registry. Recorded in a different century, to this day, it sounds futuristic.

Chris Frantz credits his other half: he'd known all along she'd transform the band. "I knew that she had a great sense of rhythm, and I knew that she shared the same kind of artistic sensibility that David and I were going for," he told MusicRadar.

"She got it. And so, had there been no Tina Weymouth in Talking Heads, we would have been just another band."

Remain In Light is available on all streaming services and from Amazon

Scott is the Content Director of Music at Future plc, responsible for the editorial strategy of online and print brands like Guitar World, Guitar Player, Total Guitar, Louder, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog, Guitarist and more. He was Editor in Chief of Classic Rock for 10 years and, before that, the Editor of Total Guitar and Bassist magazines. Scott regularly appeared on Classic Rock’s podcast, The 20 Million Club, and was the writer/researcher on 2017’s Mick Ronson documentary Beside Bowie.