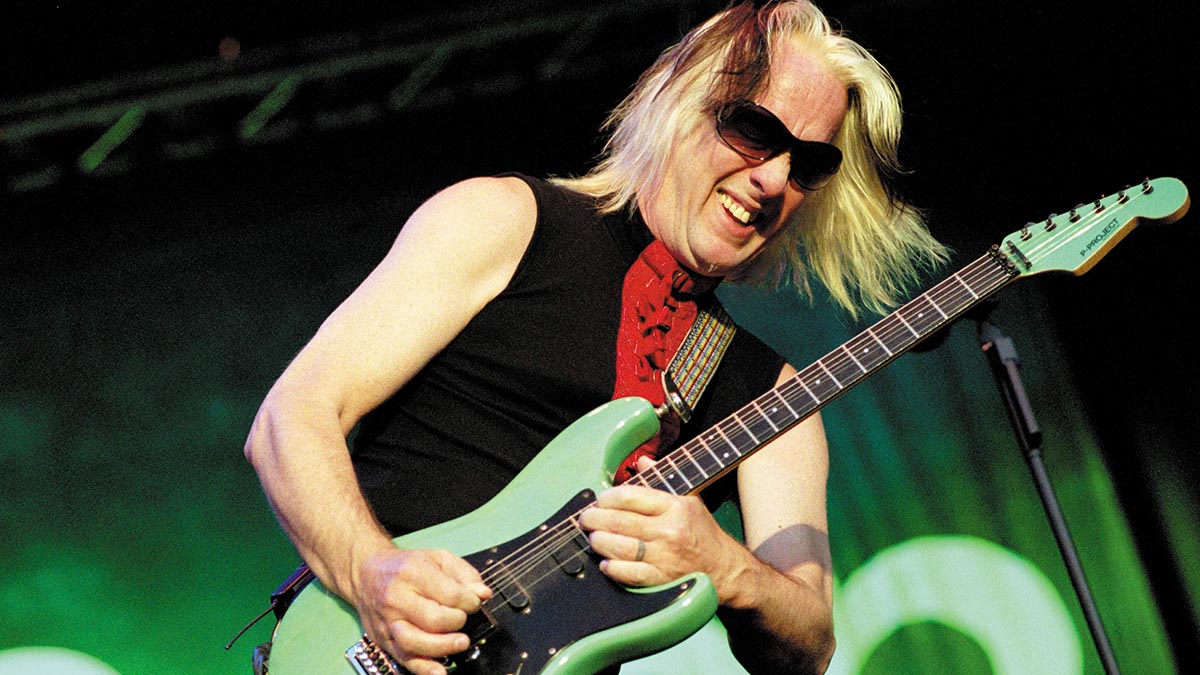

Todd Rundgren: “I reached a point with my technique where I said, ‘I don’t want to play faster than I can listen’“

The legendary guitarist and producer reflects on his prolific and stellar career

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Since the British Invasion flicked his switch as a young Philly gunslinger, Todd Rundgren has been one of US rock’s most prolific guitarists and producers.

Now, as he prepares to embark on a trailblazing virtual tour, the veteran workaholic tells us about breaking the rules, borrowing Clapton’s electric guitars, the creative benefits of LSD, and the bum notes of the New York Dolls.

Rule Britannia

“My parents got me a guitar and some lessons, and I ignored the lessons and just started picking stuff out. George Harrison’s solos in The Beatles, every guitar player learnt those literally – I mean, it was sacrilege to improvise them. But the second wave of British Invasion acts – The Who, The Yardbirds, John Mayall – that’s when I really got into the guitar.

“It was all about improvisation and the songs sometimes became secondary. It’d just be some old blues song that you rearranged just for the purposes of playing really long solos.

“When Eric Clapton made his debut with the Bluesbreakers, that was an atom bomb in the middle of the guitar world. Everyone was hanging off every note he played. I drove up to New York from Philadelphia and saw the Cream and The Who – and both bands knocked me on my ass. Every night the Cream played the Cafe Au Go Go, I was 6ft from Eric’s double Marshall stack, with my ears ringing every damn night, just staring at his hands.”

After Hours

“Eric and I were never great friends. But I met him very early in my career, when I was still just in a local blues band.

“One night, after-hours at the Cafe Au Go Go, a jam session was forming with Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters. Eric came in, but he had no guitar, and I didn’t travel anywhere without one, so I said, ‘Here, take my guitar, please.’ It was a decent guitar, some sort of Gibson semi-acoustic.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“And then I just sat there for the next hour, in a completely empty club, with just a couple of other hangers-on, watching these guys go through it, for each other, not for an audience.”

Breaking Out

“My early hits like Hello It’s Me and I Saw The Light are representative of where I was at as a songwriter in ’72. But when those songs came out and I listened back, I realised how much formula went into them.

“The reason those songs succeeded was because of their derivative nature. They plugged so easily into audience expectations. They’re easily absorbed. I realised how much more creative possibilities there were.

“After that, I completely changed my attitude to songwriting. I’d become aware early on that The Beatles were taking advantage of their pre-eminence to evolve, and drag the audience along with them. You didn’t just find a hit song then rewrite it over and over again.”

On A High

“There were things happening in society that The Beatles amplified. Like, The Beatles didn’t invent drug consumption. But they essentially made it okay for everybody and integrated it into their process – first of all with pot and Revolver, then with acid and Sgt Pepper. I had, in some senses, a similar evolution, I think.

“The first drug I took that had any effect was cannabis. It caused me to look at things differently. I started to see that things didn’t just happen by accident, and my songwriting suddenly became much more logical and the subject matter much more interesting. After the Something/Anything? album was when I got into psychedelic drugs, and I realised that I had this whole world of music inside me that I had been ignoring.”

Wizard Of Odd

“Something/Anything? was highly commercially successful, but people kept calling me the ‘male Carole King’, and saying that album was my Tapestry. So by the time we got to A Wizard, A True Star, I said, ‘This is not going to be like anybody else.’

“My whole way of thinking about music changed. I suddenly realised that a vinyl record doesn’t always have to be six songs with spaces in between. You can just fill the whole damn thing up with any kind of sound you want. That was the revolution in my head.

“I was extremely happy, having made that album. It was a kind of statement of liberation. It also culled off a whole bunch of my audience. As a matter of fact, most of the reaction at the time was negative. It was so different from Something/Anything? that everyone thought, ‘Uh-oh. He took the acid and now he’s Brian Wilson.’ But I persisted!”

The Best Of Me

“The first phase of Utopia in ’73 was probably when I was playing the best guitar of my career. My playing reached a certain level of technique, and it’s not gone beyond that. Probably, if I took a few lessons, I could learn to play faster. But I reached a point where I said, ‘I don’t want to play faster than I can listen. I don’t want to play more notes than I can actually absorb if I’m listening to it.’ I’m not interested in simply dazzling people with how fast my stuff is.

“But in Utopia, I had keyboard players to keep up with, so I did develop a certain amount of nimbleness on the fingerboard. That first Utopia line-up never actually made an album, but the shows would run four hours long, because everybody wanted to take a 10-minute solo on every song. And the audience was so high they didn’t care.”

Production Values

“Meat Loaf’s Bat Out Of Hell and the first New York Dolls record were two completely different albums to produce. Bat Out Of Hell had some of the premier musicians in the world playing on it. It was half of the E Street Band and half of Utopia, and we rehearsed for 10 days before we went in the studio and did most of it live.

“With the New York Dolls, everything that got played was live, too, but we only got a take when everybody accidentally played what they were supposed to. They were a band of guys who’d learnt just enough about their instruments to be able to play a song – and no more than that. If you tried to be a real guitar player, you were a poser, because it was really more about posing with the guitar than actually playing it well.”

Rock On Tommy

“I’ve produced a lot of great players. I’ve worked with Amos Garrett, one of the greatest guitar players that ever lived. And Rick Nielsen, who has a style like nobody else. In ’86, I produced an album called Dreams Of Ordinary Men for an Australian band called Dragon.

“They came to my place in upstate New York and for the purposes of that album they hired Tommy Emmanuel. Speaking as a producer, he’s the guitarist who impressed me most with his overall abilities. The sound he can get out of an acoustic is truly remarkable.”

Blackie Beauty

“In ’74, Eric Clapton was headlining Madison Square Garden and he invited me to jam. I’m like, ‘Oh my God, I’m actually going to play with Eric.’ So I get up there and the very first note, I bust my E string.

“Eric takes off his Blackie Strat, gives it to me and lets me play through his rig, while he called for a spare. Which was one of the most gentlemanly things a musician has ever done for me, and I’ve never forgotten it.

“I was so bedazzled at that point, I wasn’t even paying attention to how Blackie felt to play. I was too awestruck to evaluate it. I only had a few moments with that guitar, but it was one of the highlights of my life.”

All Work, No Play

“I always had a very short attention span. Not an inability to focus but an inability to focus for very long on a single thing. It made school horrible for me. If every class had been five minutes long, I would have been great. Unfortunately, the classes were an hour long and I just couldn’t sit still for that long.

One of my favourite guitars I ever had was an Olympic electric with a piezo in the bridge... I’d get the most remarkably crystalline sounds

“I guess I’d call myself a workaholic, in the sense that if I go without working for too long I start to feel guilty. But I’ve also come to realise, over time, that most of the work goes on inside my head. So it may appear as if I’m not working at all, but then, once I do get down to it, it takes a lot less time to accomplish something.

“With a guitar part, I’ll sort of half-imagine it and then I’ll have to work it out on the guitar because of the limitations of my playing. In other words, it’s possible for me to imagine things that I can’t play, that are banging up against the limits of my technique.”

Back To Basics

“There was a reinvention for me on the Nearly Human album [in 1989]. In the 80s, the recording process had gotten very sterile. Back in the 60s, with my band the Nazz, there was no overdubbing. But as time went on, it became more and more of a process of layering up sounds.

“Records were these giant anal exercises and you wouldn’t know what you had until the very last guy put his overdubs on. With Nearly Human, I thought, ‘Let’s try doing it the old-fashioned way.’ So everything was live in the studio, no overdubs.”

OK Computer

“Long before the major labels started to collapse, I realised they weren’t going to adapt to the internet. So I got off Warner Brothers in about 1990 – and I’ve never signed with a major since. I realised that you could eliminate the record label out of the equation, go directly to your audience.

“That means there’s gonna be a lot more crappy music out there. But it also means there’ll be a lot more interesting music that might not have gotten heard otherwise. I think it’s great that technology has become much more accessible, and now you don’t have to be rich or get permission from a label – you can just get it in your head to do it.”

Rack ’N’ Roll

“One of my favourite guitars I ever had was an Olympic electric with a piezo in the bridge. Before it was stolen, I used that guitar extensively on Hermit Of Mink Hollow and The Ever Popular Tortured Artist Effect, and I’d get the most remarkably crystalline sounds, a hybrid between acoustic and electric.

“I owned Eric Clapton’s ‘Fool’ SG for a long time. I got it from Jackie Lomax. I think he got it from George Harrison, who in turn had gotten it from Paul Kossoff. Jackie was in hard times and he offered to sell the guitar. I went over to see it and it was in ruins, paint chipped off all over the place.

“I played it for a while in its original condition, but under the headstock, Eric had played it so much that it’d sweated off the paint and through the wood, and eventually the headstock snapped off. I had a new headstock made, had the paint job restored and played that guitar for years. But then I got in trouble with the IRS in the 90s and had to auction it off.”

On The Road Again

“What’s on my mind today? Well, right now, I guess my biggest concern is that my whole band and crew are off to Chicago to livestream the Clearly Human Virtual Tour project in the middle of an ongoing pandemic. We need to have strict protocols, testing, all our ducks in a row, the whole deal, if we’re going to pull this off. So I’m most apprehensive about our ability, regardless of how scrupulous we are, to maintain consistently negative test results for the entire two months of this project.”

Out Of This World

“My latest record, Space Force, is all over the place. It’s another album of collaborations, so every song is different in terms of instrumental make-up and who’s playing on it. I’m doing something of a ballad with Adrian Belew. I’m doing what I’ve decided is an animé soundtrack with Steve Vai, and then a good old-fashioned angry rock song with Rick Nielsen. So it’s going to be a challenge for me to keep up with them!”

- Todd Rundgren's Nearly Human – The Deluxe Edition is out now via Friday Music.

Henry Yates is a freelance journalist who has written about music for titles including The Guardian, Telegraph, NME, Classic Rock, Guitarist, Total Guitar and Metal Hammer. He is the author of Walter Trout's official biography, Rescued From Reality, a talking head on Times Radio and an interviewer who has spoken to Brian May, Jimmy Page, Ozzy Osbourne, Ronnie Wood, Dave Grohl and many more. As a guitarist with three decades' experience, he mostly plays a Fender Telecaster and Gibson Les Paul.