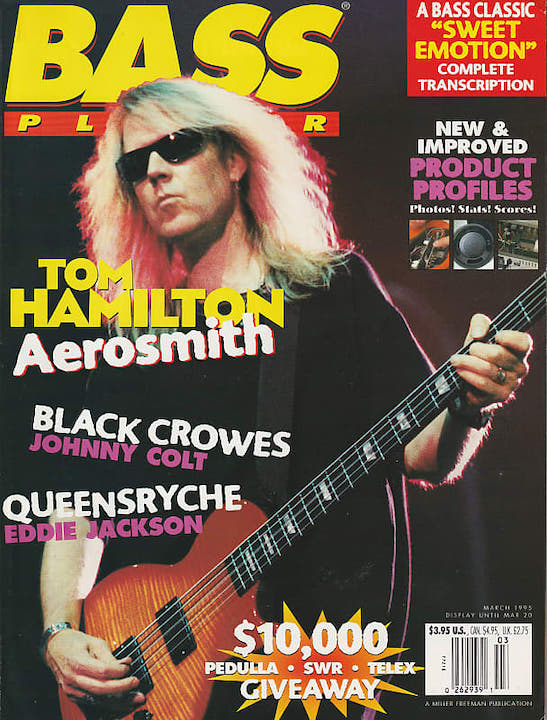

Tom Hamilton: "I thought, I'll be damned if I'm going to play eighth-notes on the root all my life!"

Aerosmith’s long-serving bassist reflects on becoming a "music-book junkie", channeling John Paul Jones and "smoking a bowl" before writing Sweet Emotion

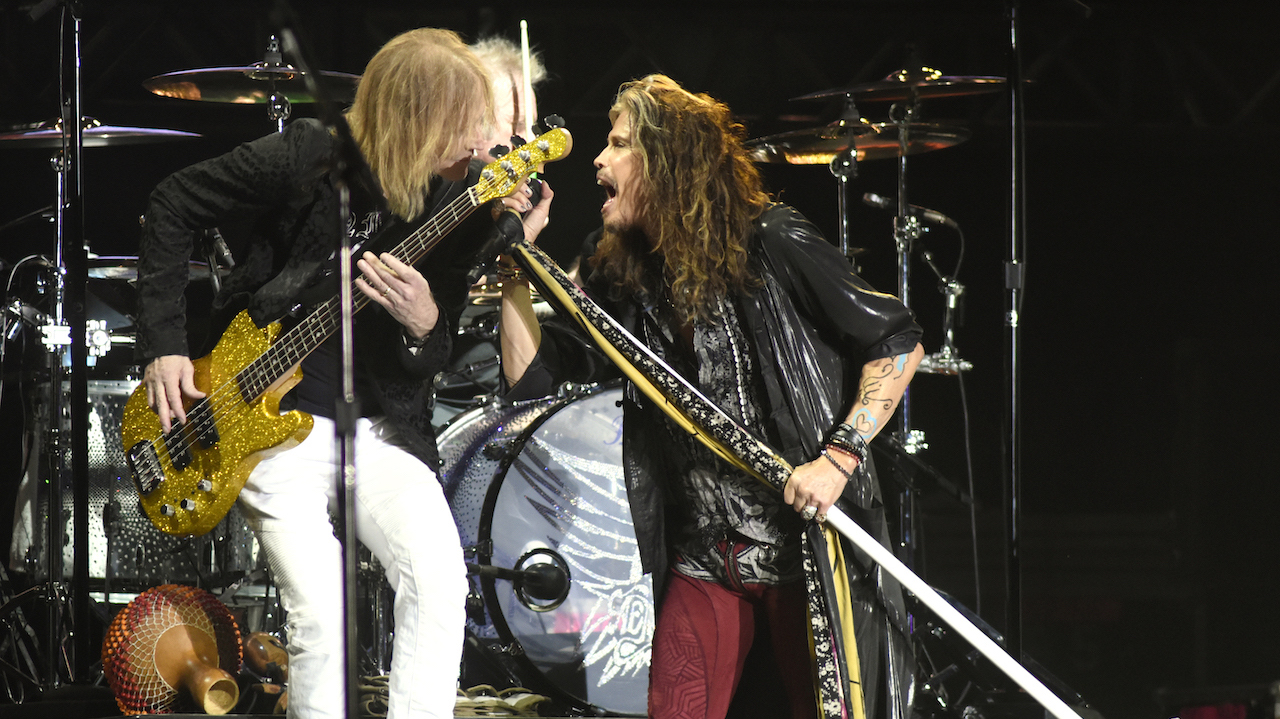

Okay, so they may not be the ‘World’s' Greatest Rock & Roll Band – the Rolling Stones soundly re-established their claim to that title – but Aerosmith remain one of the hardest-working bands around – and one of the most successful. Bassist Tom Hamilton has been an essential ingredient in the Aerosmith formula all along, from his classic composition Sweet Emotion on the band's 1975 breakthrough record, Toys in the Attic, to his rock-solid grooves on the 1993 multi-platinum disc, Get a Grip.

"Playing bass guitar in this band has been such a learning process for me," says Hamilton. "At first, the guys would say, ‘Play the root! Stick to the root!’ I thought, I'll be damned if I'm going to play eighth-notes on the root all my life! So I had to learn to be sneaky and try to take the music to the next level, while still serving the songs."

Following a brief, unofficial breakup during what Hamilton calls "the limbo years" in the early 1980s, a period that was troubled by substance abuse and vicious in-fighting, the original lineup reunited in 1984, and christened their comeback by collaborating with rap group Run-DMC for a hip-hop treatment of the Aerosmith staple Walk This Way.

Aerosmith didn't really get airborne again, though, until the release of 1987's big-selling Permanent Vacation; they rocketed to the stratosphere two years later with Pump.

The following interview is from the March 1995 issue of Bass Player, which followed the band's third consecutive multi-platinum album, Get a Grip.

How do you see your function as the bass player in Aerosmith?

"I'm basically employed by the song. My role is to get together with Joey and create a really solid groove and foundation; once we get that happening, I go up to the practice room and play the song over and over, trying to come up with little nuances and bits that put my stamp on it. Aerosmith has always tried hard to put the song on a pedestal and to keep the individual musical statements to just what's called for – and that usually means a pretty minimal bass part. That was especially true in the beginning."

On the Making of Pump video, you mention that when you finish recording your parts, you always feel as though you don't want to stop.

"It's always been that way. I love being in the studio, but I always work and work to get prepared for it, and then it's all over in about two weeks. I've found that the only way to practice being in the studio is actually to be in the studio. You can get ready for it at home, but being really present and putting down your best stuff when that red light goes on – you have to practice that by doing it. It's frustrating, because usually by the time the basic tracks are done, I'm just starting to feel comfortable and starting to be spontaneous instead of sticking strictly to my parts. I'm on this ascending curve and suddenly it's like, chop!"

Do you hang around for the rest of the recording process?

"I usually hang around for about a week or so, but we're usually recording somewhere like Vancouver, and it's hard to justify the expense of keeping everyone there. We always stay in close touch about how the songs are developing."

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Do you attend the mixing sessions?

"No. We've found that it's counterproductive for everyone to be there for the mix. Steven and Joe are there, mostly because they do the bulk of the writing. If someday I manage to sleaze some more of my writing onto an Aerosmith record, I'll want to be there for those mixes."

How much writing do you do for the band?

"I've got a lot of cool material, and hopefully at some point we'll get a chance to use it. That's how it happened back in the '70s; our producer, Jack Douglas, was very much into trying everything, and he was very good at encouraging an experimental atmosphere. That resulted in songs like Uncle Salty, Sick as a Dog, and a few others I co- wrote with Steven."

On the Get a Grip tour you played a bass solo that led into Sweet Emotion. How did the solo come about?

"I just started doing it one night, and I got a lot of encouragement from the band, which implied a kind of dare: 'Wow, that was cool – but do you have the balls to do it every night?' Our band is full of that kind of stuff."

What instrument do you usually write on?

"When I write, I usually turn on the drum machine and play along. Whether I'm playing bass or guitar, I keep the tape rolling the whole time, and something usually pops out that I think is cool. I'll start working on it – and the next thing I know it's two hours later and it's time to think of another part. One thing I've found is that when I'm sitting there playing, it's easy to play something and go past it, thinking it was just a musical belch. But the smallest element can be the basis of a cool riff, and that can be the basis of a whole song. That was how I wrote Sweet Emotion – the intro was the first thing that came along."

How much of that song did you write?

"I wrote pretty much all of the bass and guitar parts. I first showed it to Steven for the Get Your Wings record, but he was hearing the ‘one' in a different place, and he couldn't understand what I was doing. So next time I tried it his way, and I realized it was more understandable. The middle riff that comes between the verses was inspired by Jeff Beck's Rough and Ready. We had this crude sound system in our apartment; everyone would latch onto a particular record and play it for days, and Rough and Ready was one of those. I'd get the basic feeling of a record in my head, and then I'd want to spit it back out."

What did you play first guitar or bass?

"Guitar. My brother had a nice Fender Strat and a Twin Reverb amp, and he taught me my first chords. We lived in a little town in New Hampshire called Andover, and there wasn't a big pool of musicians there – and everyone who wanted to play wanted to be a guitarist. Since I was the last one to join what was pretty much the only band in town, they said, ‘Hey, you can be in if you play bass.’ I had a Precision Bass at first, and then a couple of years after I got it I traded it for a Mosrite – one of my first big mistakes."

What was the musical environment like at home?

"There was always music in the house, although neither of my parents played an instrument. There was a lot of Frank Sinatra around, and also a lot of show-tune records like My Fair Lady and South Pacific. My dad also had records of steam trains, which was probably what got me into low end. They'd be having a party, and we kids would wake up in the middle of the night to the sound of trains roaring through the house. That's when we knew the party was really happening!"

What kind of music were you into when you picked up the guitar?

"The Ventures. There was this record called Play Guitar with the Ventures, and it was one of the best-organized instructional products I've ever seen – even to this day. It had its own form of tablature, along with ‘Music Minus One’ recorded versions of songs like Pipeline and Walk – Don't Run. Then the Beatles played on the Ed Sullivan Show, which was a crisis for me. I was blown away, but I felt as though I was deserting the Ventures for a group that had vocals. That feeling lasted about five minutes, and I was a wicked Beatles fan from then on."

A tiny New England town and a bassist who wasn't really sure how to play – these aren't the ideal conditions for the formation of a record-breaking rock band. Yet somehow Aerosmith took root. Fifteen albums and 70 million record sales later, Tom Hamilton recalls the band's early years.

How did you hook up with the other guys in Aerosmith?

"We lived in something of a resort area, and in the summer all of these kids from Boston who were really good players would come up. They'd become the local legends – you could jam with them, learn stuff from them, and put together bands with them. One summer I started jamming with a drummer named Dave Scott; we decided we needed a guitar player, and he knew this guy named Joe Perry who was washing dishes at a restaurant in town. We put together a band and started learning Hendrix, Beatles, and Cream songs; we had a blast playing loud and letting our imaginations take over. At the end of the summer Joe and Dave went back to school, and I basically spent the winter not being in a band. Then the summer came around, and we put the band back together."

What were your feelings when Aerosmith started to get big?

"I think I took it for granted. It was never a surprise that we were making it – it was exhilarating, but not surprising. We weren't there just to play our instruments and make music – we were there to make it and live that life, but I was also in a state of confusion; I felt as though I was on thin ice in terms of relating to people in the record business, doing interviews, and everything. I also felt off-balance because of the incredible tension and discomfort that was going on in the band, which turned into overt fighting later on."

Do you think such tension can be creatively stimulating?

"I think it serves the music, at least to a certain extent. It inspires competition. There are a lot of ways tension isn't healthy, though. If musical ideas don't get brought out into the light and tried out, then it's not good. This band has never been the kind where everyone shows up and gets a shot; you really have to fight for your space. That's a law of nature – survival of the fittest – but it always bothered me that the band atmosphere wasn't as easy or loose as it could be."

How did you feel when the band broke up?

"It was a relief – and when I look back on it, I realize how sick that was. We cancelled the rest of the tour, and I actually felt good about it; that was the kind of confusion and disorientation I was feeling at that time. Don't get me wrong – being in the band was exciting. It's just that now I feel so much more comfortable with going onstage and having fun, and I no longer feel as though I have to be drunk to play my parts."

Did you manage to restrict your usage to alcohol and cocaine?

"I did it all, but pot was really my thing. There was a time when I came up with some really good musical ideas on pot – I probably smoked a bowl just before I wrote Sweet Emotion – but I needed to quit doing it, because I basically couldn't finish a sentence. There's a period you need to go through where you re-establish your faith in your own creativity – where you realize you don't have to be buzzed to create. The buzz frees you up, but you have to understand that the creativity is already there – you just have to have faith in it."

How did you feel when Aerosmith re-formed?

"After Night in the Ruts came out, we went on tour, and I had a wake-up call: the numbers dwindled. People didn't show up, and they didn't like the record. I saw that Steven wasn't ready to create the same bond with guitarist Jimmy Crespo that he had with Joe. Jimmy was brilliant. He came up with some great riffs and had a lot of musical knowledge, and he was very good technically – but I don't think Steven was ready to let go and let the creativity between them happen."

Why do you think Permanent Vacation was so successful?

"On Permanent Vacation, we worked with producer Bruce Fairbairn, who was a very demanding, focussing, no-bullshit influence. Bruce was there to make sure the conditions were right to let the creativity happen, and he had the ability to get us to play better than we ever thought we could. That period was challenging and exciting for me, but it was also painful; there wasn't a lot of opportunity to experiment with different, off-the-beaten-path stuff. The band had made a decision that we wanted to re-establish ourselves, and that took priority."

That decision paid off, as Aerosmith made one of the greatest comebacks in rock history. Not only was Permanent Vacation a smash hit – the follow-up, Pump, blasted beyond the band's previous numbers. Then, in 1993, the band released yet another chart topper, Get a Grip, which spawned an 18-month, 200-show world tour. The nearly four million fans who attended didn't go home disappointed: every night, the band put out as much turbocharged, light-'em-up rock and roll energy as any bunch of 23-year-olds could.

Do you have a ritual you go through before a show?

"We do a meet-and-greet for the fans and the press before each show, and how long that runs determines how much time I get to warm up – but usually I try to play for half an hour. It's important for me to warm up, because I've had problems with my joints and tendons, and between my two hands I have about five joints that seem to be saying, ‘You'd better watch it, pal!’ I got this great book called Bass Fitness by Josquin des Pres."

Have you found that warming up actually makes you perform better?

"I wonder about that sometimes. There have been nights when I've had to run onstage without even having picked up a bass. I don't like to do that because I don't feel stretched, so I feel I have to be careful at first. What really affects the show for me, though, is the acoustics of the room – especially how the PA is sounding. It's amazing how much the sound out front affects my bass sound onstage. Depending on where we are, sometimes we get a lot of bass from the PA coming back onto the stage, but it doesn't come back as nice, clear bass – it comes back as low-end noise. When that happens, I get dirty looks."

Do you do anything to get emotionally prepared for a performance?

"It's weird, but just changing my clothes does a lot. What you put on becomes a symbol of what you're about to do. Aside from that, the meet-and-greet tends to put us into performance mode. So much of our show involves relating to the audience. I really try to make eye contact with people, and I derive a lot of my inspiration from seeing them having fun – it makes it possible for me to play Dream On for the zillionth time. It's easy for it to become rote, but if I see someone in the audience who's really loving the music – a couple making out, or someone who's saved his last joint for the song – I tap into their enthusiasm, it rekindles mine, and all of a sudden it's not an old song anymore."

You mentioned that you've been filling in the holes in your musical education. How are you doing that?

"I'm going back to my old records and learning the basslines. There's a Van Morrison song called Moondance that has a great bass part. I learned the whole song bit by bit. There are a lot of notes the bassist uses that I've always thought weren't kosher, but it's cool because they give the song a certain sound. That has reassured me about some of the notes I played when we were first starting – maybe they were okay after all, without my knowing why."

"I'm also a frustrated music-book junkie; I go into music stores and look through the bass books, and since I don't read music all I see is a bunch of dots and lines. Then I look at the guitar rack, which is five times as big, and it has detailed tapes and tablature analyses of all these different guitar players and their solos – and I just get pissed off. I don't understand why someone hasn't written a book on John Paul Jones, with recorded versions of sections of songs along with analysis. Hopefully, someday I'll have the time to do something like that. I can visualize how it would look, and it would be very simple and to the point. Putting together something like that would be a great learning experience, too."

There are some players who feel such non-traditional learning methods are more harmful than helpful in the long run.

"To them, I say: Come down off your high horse! There are a lot of bassists out there who are very talented and creative but don't read music. Some of them even play basses that have only four strings! I shouldn't talk, though, because I play a 5-string now. I used to think 5-strings were for eggheads – now I think 6-strings are for eggheads!"

How long have you been playing 5-strings?

"Since we recorded Get a Grip. I suppose I'd rather play a 4-string, because the string spacing is easier to deal with, but I like those low D's and C's. I tried the Hipshot XTender, but it didn't work too well for me. Because of the way our stage is set up, if I'm all the way over on Joe's side, away from my amp, sometimes I can't hear myself at all; it just blends in with the wash. And if I forget to flip that Hipshot back up, I fuck up in a major way in front of a lot of people. That happened a couple of times."

How often do you go down to D and C?

"I spend most of my time on the top four strings, but on Dude Looks Like a Lady I use the B string for almost the whole song, and on Fever I do these walking lines from hell that go way down. I also like being able to play low E at the 5th fret; that opens up patterns you can't use on a 4-string. It took me a long time to keep from thinking the big string was the E, but all of a sudden I got past that and it was no problem."

What needs do you have left to fulfill?

"Bass-wise, I just want to learn more about the instrument. It's all been guesswork for me, and I feel as if I've had to fight for every bit of musical progress I've made, but I just want to keep inching forward. When I study what someone else has done, a lot of times I think, ‘Wow – he's using basically the same stuff I know, but in combinations I haven't tried before.’ So it's nice, because I'm finding I know more than I thought. I definitely have specific goals for bass, but they're pretty much the same as my goals in all areas of music."

Aerosmith's 40-date Peace Out North American tour will kick off in Philadelphia, PA, on September 2. Tickets are available now from aerosmith.com .

Karl Coryat was Deputy Editor of Bass Player magazine in the 1990s. In the 2000s, he wrote two music books: Guerrilla Home Recording and The Frustrated Songwriter’s Handbook, the latter with Nicholas Dobson. In 1996, he was a two-day champion on the television game show Jeopardy!. He works as a comedian and musician under the pseudonyms Edward (or Eddie) Current.

- Nick WellsWriter, Bass Player