Ensemble-Oriented Composing, and How to Play "Atlantic Limited"

Julian Lage teaches an important skill for any guitarist—how to "sit out" and let the rhythm section take the lead.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For me, composing music is a form of therapy: I will write something and then try to look at it objectively and ask myself, “Is that who I am?,” or “Is that what’s coming out right now?” For a while now, I have been thinking that I want to write less in a given composition: fewer chords, simpler melodies and harmonic structures, etc. It then occurred to me that the thing I have not done enough of is to write songs that require me to sit out — stop playing! — and let the rhythm section take the lead.

There’s a song on my new album, Modern Lore, called “Earth Science,” that involves exactly what I’m talking about here. It’s built around a melody that was primarily inspired by the great jazz saxophonist Ornette Coleman. If you’re unfamiliar with Ornette’s music, his writing is so vast that I can’t even begin to summarize it. But one of the great tenets of his music is that it is always very melodic, and it often is not tethered to any chords, per se. That’s the approach I took in composing “Earth Science.”

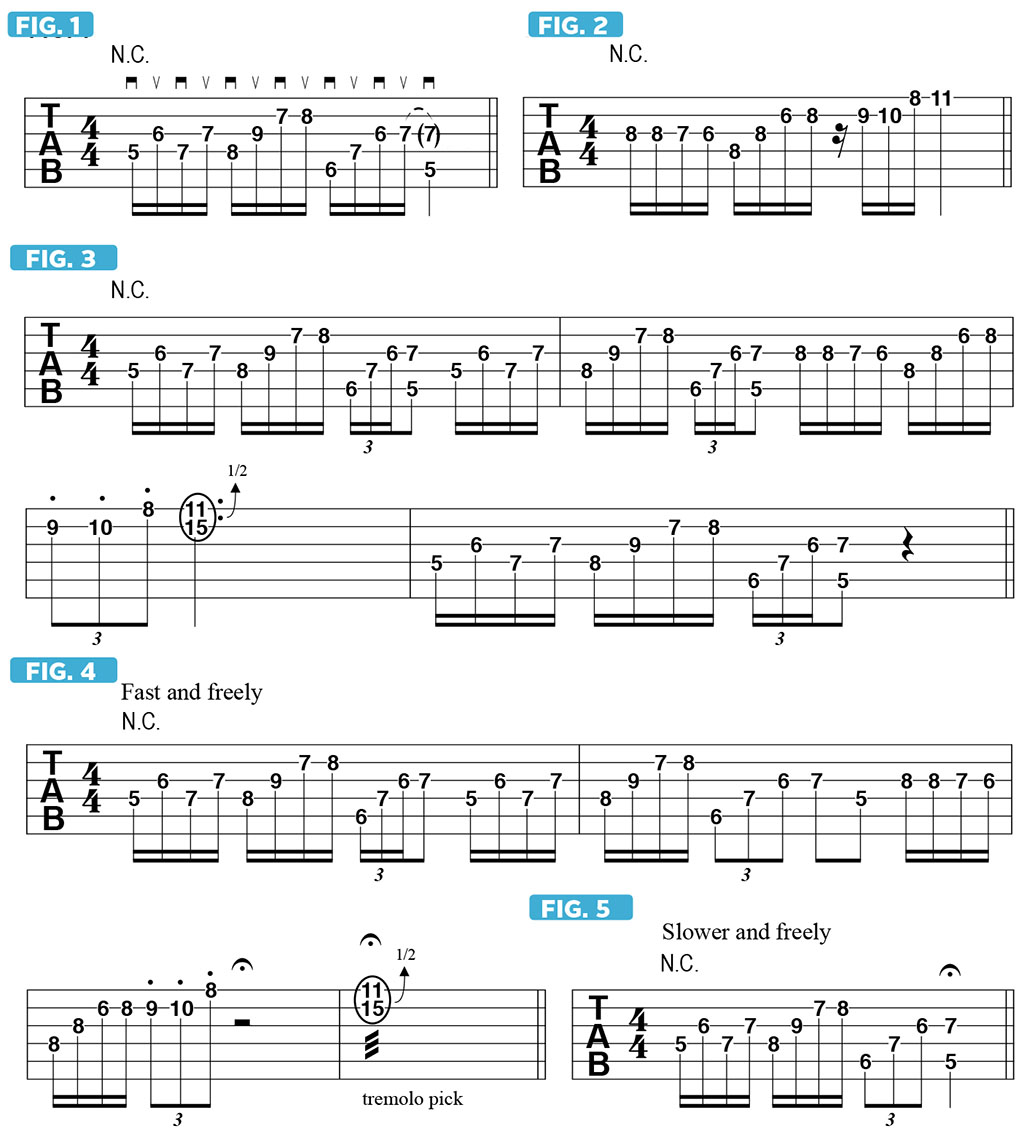

FIGURE 1 illustrates the tune’s main melody. Played as straight (even) 16th notes, it does not reference or outline any specific chord and is built from pairs of notes that move in a somewhat chromatically ascending manner. Guitarist Nels Cline refers to this type of melodic line as a “squib,” something that ignites the music. I challenged myself to write a bunch of melodies like this, and so one day I sat in a coffee shop in Nashville and just wrote a bunch of them down on music paper. I don’t have perfect pitch, so oftentimes when I sit down to play what I wrote away from the guitar, I realize that some of the pitches are off from what I intended. But every so often, I find something cool, and the melody for “Earth Science” was born in this way.

FIGURE 2 shows the next melodic segment, which again features a series of chromatic passages, both descending and ascending. This is followed by a repeat of the first melodic line.

Ordinarily, I would then write a form to solo over and forge a musical environment to feature the guitar. But instead, I flipped the script by laying out and featuring Scott Colley on bass and Kenny Wollesen on drums with a simple musical direction: play together, play fast, play dense and create so much tension that I can’t wait to come back in and interject.

These are the kind of cues you can have in a great ensemble, where you ask your fellow musicians to elicit something from you, saying, “I need you to pull something out of me that I can’t pull out of myself.” All of the great bandleaders seem to do that, and it’s something I aspire to do myself. The twist here is that I limit myself to playing only the notes of the melody, so when they build up a level of tension, I can only come back with something like FIGURE 3, wherein I play the line freely, speeding up and/or slowing down, and adding the unison bend at the end.

On the recording, the rhythm section then creates even more cacophony, with some overdubbed arco (bowed) bass from Scott, so I come back in with a faster version of the line, ending with a tremolo-picked frenzy on the unison bend, as shown in FIGURE 4. Then we all come in together on the first phrase, a little slower, as shown in FIGURE 5.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

I look forward to writing more tunes like this, and I continue to be amazed by how effective the music can become when I stop playing, and by the things that a great band can allow you to do.