Guitar 101: Learning Harmony Through Six-Note Hexatonic Scales, Part 1

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Anyone who’s ever made an effort to learn some music theory knows that one of the biggest turn-offs is the sound of the major scale harmonized in triads (three-note chords). But before you dismiss the intellectual approach to learning music as being hopelessly tedious and uninspiring, realize that it doesn’t have to be that way.

To that end, I’d like to turn you on to an unorthodox method of teaching yourself harmony on the guitar that’s fun, relatively easy and won’t make you become clinically depressed. The entire approach is based on combining pairs of mutually exclusive triads to create six-note hexatonic scales, which happen to sound very musical. The only rule is that the two triads can’t share any common tones, because then you wouldn’t have six notes, would you?

Unlike the standard seven-note scales and modes, most of which have a rather boring contour (too many notes too close together) or the primitive- and hollow-sounding five-note pentatonic scales, the hexatonic scales have a very balanced and inherently interesting quality that lends itself exceptionally well to melody and phrasing.

Still with me? Okay. Allow me to illustrate. FIGURE 1 depicts the major hexatonic scale—I like to call it the “gospel” scale, or the “Wonderbra” scale, because it sounds so uplifting—harmonized up the neck on the top three strings in the key of E (a rather useful guitar key). As you can see and hear, this very soothing and “down home”-sounding scale is comprised of E major (E G# B) and F# minor (F# A C#) triads (E G# B + F# A C# = E F# G# A B C#).

As you strum (or pluck) this chord-scale, notice the way the two alternating triads (E and F#m) leapfrog over each other up and down the neck, producing a very satisfying feeling of harmonic tension and release. You can also look at it as playing the same scale up and down three strings at the same time. Practice this figure slowly and listen closely to the way the individual voices move within each triad inversion (ear training is the key to musical growth!). If you play only the notes on the high E string, you’ll discover that this set of tones may also be reckoned as either the E major scale (Ionian mode) without the annoying seventh (D#) or the E major pentatonic scale with the fourth (A) added.

Let’s look at some useful applications of this sweet-sounding scale (all examples are in the key of E). FIGURE 2 is a smooth legato run in the ninth position that works its way across the neck using ascending hammer-ons and descending pull-offs. Notice how the E major chord tones (E G# B) land squarely on each downbeat.

- FIGURE 3 is a classic Allman Brothers–style syncopated melody harmonized in thirds and fourths, à la Dickey Betts.

- So what is it about the number 6 that makes it so conducive to rhythmic phrasing? Perhaps it has something to do with the fact that 6 is a factorable number (2 x 3), whereas 5 and 7 are prime? While you’re pondering that phenomenon, check out the way FIGURE 4 just seems to roll right off your fingertips.

Here’s a musically gratifying and technically invigorating pattern for you to play around with (FIGURE 5). Not a bad way to learn and practice two different sets of arpeggios, eh?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The information presented in this lesson is merely the tip of the musical iceberg when it comes to hexatonics. Over the next several columns we’ll be checking out an interesting variety of exotic six-note scales that will no doubt make you want to further explore this fascinating approach to harmony and melody.

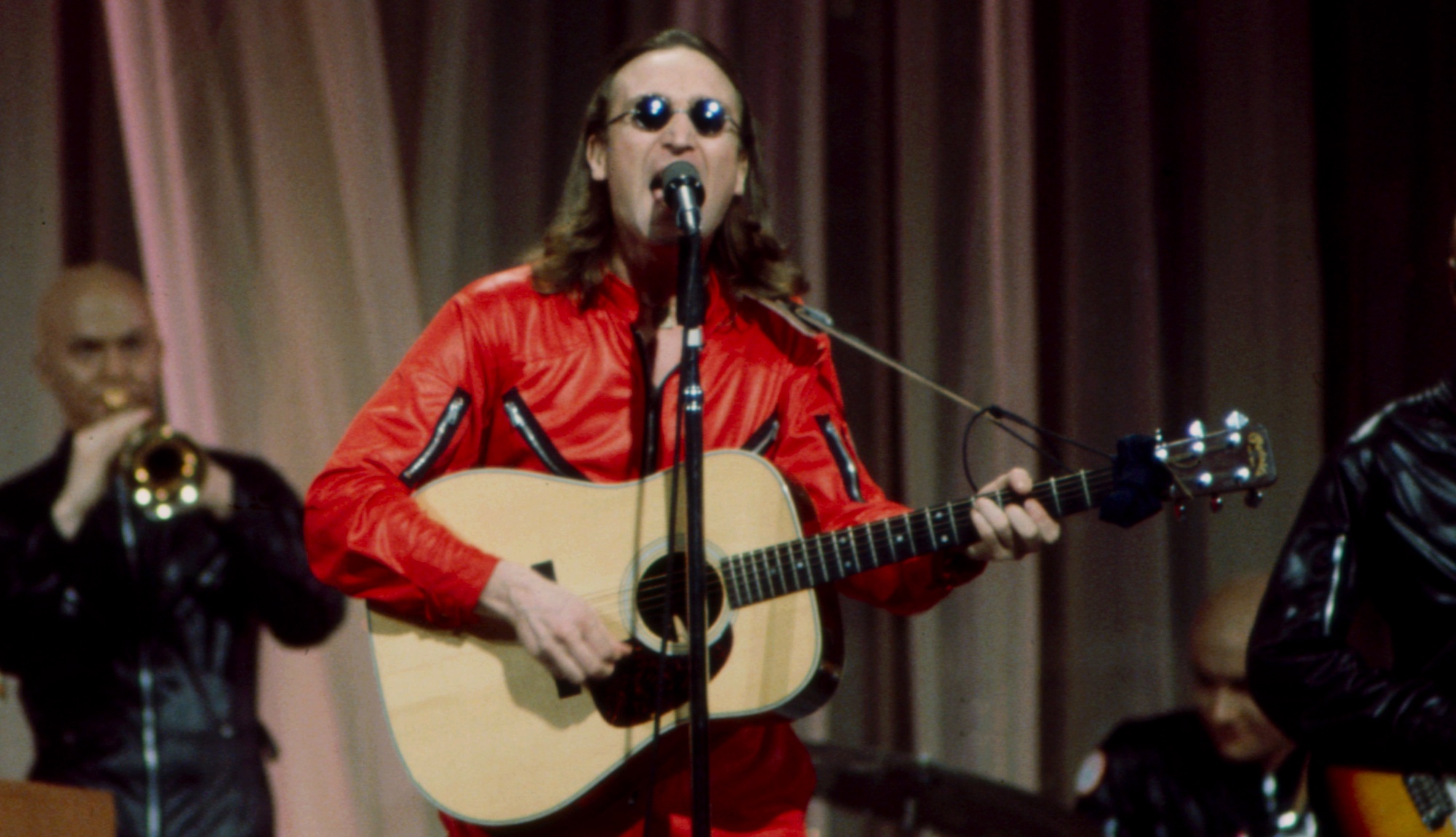

Over the past 30 years, Jimmy Brown has built a reputation as one of the world's finest music educators, through his work as a transcriber and Senior Music Editor for Guitar World magazine and Lessons Editor for its sister publication, Guitar Player. In addition to these roles, Jimmy is also a busy working musician, performing regularly in the greater New York City area. Jimmy earned a Bachelor of Music degree in Jazz Studies and Performance and Music Management from William Paterson University in 1989. He is also an experienced private guitar teacher and an accomplished writer.