Learning the A7 Dominant Chord

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If you are fairly new to the guitar, you may very well look at a chord chart and see a chord with a “7” next to it. That indicates a very specific type of chord that has a wide array of functions. Today, we will talk about its theoretical construction, some of its many uses and different ways you can play it all over the neck in different inversions.

This mysterious “7” next to the chord makes it a dominant 7 chord. To understand what that means, let us first go over some basic chord construction. Since we have an A7 chord, we'll explain this with its corresponding key signature, D major.

The Theory

In D Major, we have 7 notes with two of them raised. D E F# G A B C#

Typically, the dominant 7 chord is built off of the 5th scale degree, so we are thinking of this from the 5th mode of D Major, A Mixolydian. A B C# D E F# G

Keep that in mind, as we will come back to it. Now, let’s discuss some basic chord construction. Chords are typically built using a root, 3rd, and 5th.

In the key of D Major, that makes the following chords:

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

D = D F# A

Em = E G B

F#m = F# A C#

G = G B D

A = A C# E

Bm = B D F#

C#dim = C# E G

To create chords, you are basically taking notes in the key and skipping every other note until you get root, 3rd, and 5th.

The same principle applies with a 7th chord.

For D Major, here are the 7th chords:

Dmaj7 = D F# A C#

Em7 = E G B D

F#m7 = F# A C# E

Gmaj7 = G B D F#

A7 = A C# E G

Bm7 = B D F# A

C#m7b5 = C# E G B

Shapes On the Fretboard

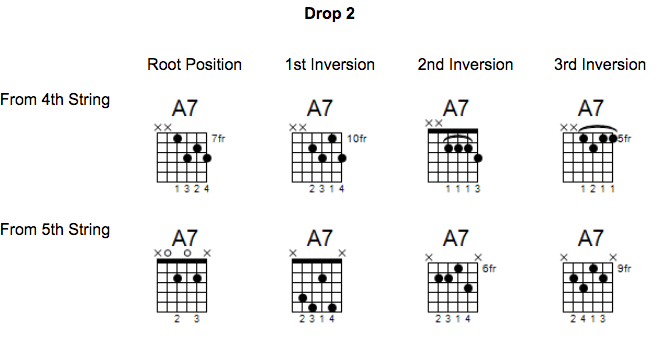

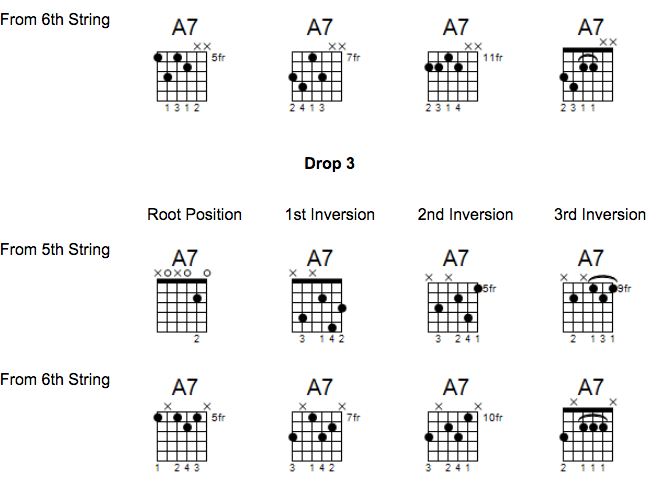

Next, let’s discuss some of the many ways this one chord can be played on the guitar. All too often, guitarists learn one or two shapes for the chord and don’t really go further than that. It’s always important to take anything you learn on guitar and learn how to play it all sorts of different ways. This is the only way you will really internalize it while improving your fretboard awareness.

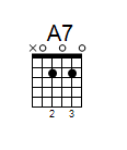

First, the classic open position shape:

Next, let’s go over drop 2 and drop 3 voicings and their inversions:

Applications

Dominant to Tonic: Dominant chords have a wide array of applications in music.

The first one of these is, of course, to set up the I or tonic chord. This is achieved through the application of voice-leading chords properly.

Let’s go ahead and discuss that a bit.

As we mentioned, the dominant chord’s job in typical functional harmony is to set up the I chord. This means that A7, which is a tense and unresolved chord, sets up the D major, which ends up feeling like “home base”. Going over this concept in depth is probably beyond the scope of this lesson, but let’s quickly take a look at how this works.

The dominant chord in D major is made up of the following scale degrees: A (5), C# (7), E (2), and G (4). The 7 (C#) is a half-step below the tonic (C# to D), and the 4 (G) is a half-step above the 3rd or the mediant (G to F#). This half-step distance at these particular points in the scale make it feel like they want to pull up or down respectively. You can try this on a guitar or piano to see for yourself.

Blues: In a basic blues progression, we see that the dominant chord takes on a mind of its own. Here, it doesn’t always necessarily serve to set up another chord, but instead, is considered a “stable” chord itself.

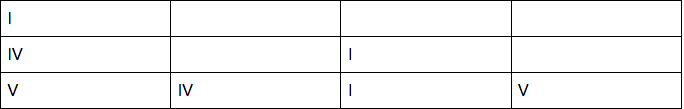

In a basic blues progression, you have the following progression:

These chords also happen to all be dominant chords, interestingly enough.

What I love about this particular trait in the blues is that a dominant chord is typically considered a “tense” and unresolved sound. In the blues, however, it still has all of that tension that we love about dominant chords, but they also sound stable.

Tonicization and Tritone Sub: Another neat function of the dominant chord is that you can set up virtually any major or minor chord by playing a dominant 7 chord a 5th above the root.

If you want to tonicize C, you can play G7, if you want to tonicize A, you can play E7, and so on. In addition, you can achieve this same effect with some added interest by playing a dominant 7th chord a half step above your target chord. For example, to tonicize C, you can play Db7, to tonicize A, you can play Bb7. This is called a tritone sub because you’re substituting the original dominant 7th chord with one that is a tritone away from the root. That means that instead of G7, you’d play Db7, and they just happen to have the same 3rd and 7th, but inverted!

G7 = G B D F

Db7 = Db F Ab Cb (or B)

The B and the F are the important notes here and they both serve to set up the C chord accordingly.

There are even more functions available for dominant chords, but these are some of the big ones.

A few notes before closing up shop here. When learning these shapes, it’s important that you identify each note in the chord and where it lands in the chord shape. This way, you can move these shapes around and use them in other keys with ease. I would also strongly recommend practicing these in cycles. Take, for example, the circle of 5ths, grab a shape, and go through all 12 keys in one position, then repeat in the rest of the available positions.

Marc-Andre Seguin is the webmaster, “brains behind” and teacher on JazzGuitarLessons.net, the #1 online resource for learning how to play jazz guitar. He draws from his experience both as a professional jazz guitarist and professional jazz teacher to help thousands of people from all around the world learn the craft of jazz guitar.