How to Play Soul-Blues Rhythm Guitar

The chords, patterns and tricks you need for King, Cropper and Hendrix-style soul

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

By the early Sixties, the blues branch of the popular music tree was rapidly thinning. One of the main factors contributing to its demise was rhythm. After decades of dance-floor popularity, triplet-based shuffles and swing grooves had started to be viewed as decidedly old-school, eclipsed by the straight-eighth-note-based rhythms of R&B and rock and roll.

Among the popular syncopated styles to emerge on the R&B side was southern soul (often called simply “soul”), which originated out of studios in Mussel Shoals, Alabama and Memphis, particularly Stax Records and its house rhythm section of Booker T. & the MGs. Soul singers such as Wilson Pickett and Otis Redding rose to stardom with hits like “Mustang Sally” and “I Can’t Turn You Loose” that borrowed nearly everything from blues and gospel tradition except the beat. The message, however, was clear: the future belonged to the funky.

This shift in popular tastes upended the careers of many traditional blues-based artists, although some—Freddie King, Buddy Guy and Magic Sam among them—managed to roll with the changes. The most successful soul blues guitarist of the decade was Albert King, who ignited his previously modest career when he signed with Stax in 1966 and began turning out classics like “Born Under a Bad Sign,” “Oh, Pretty Woman,” and “(I Love) Lucy.” King’s success in grafting stinging blues guitar to hip grooves not only made him a star but also served as a model for up-and-coming blues-rockers like Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix.

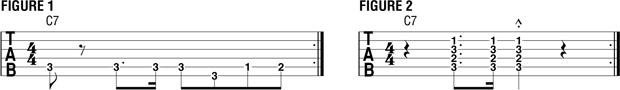

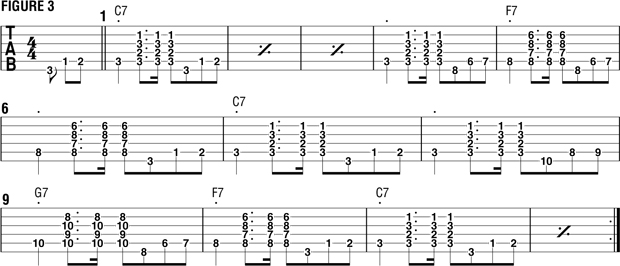

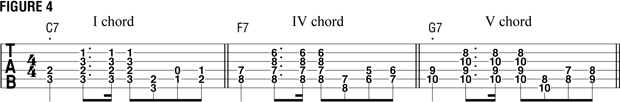

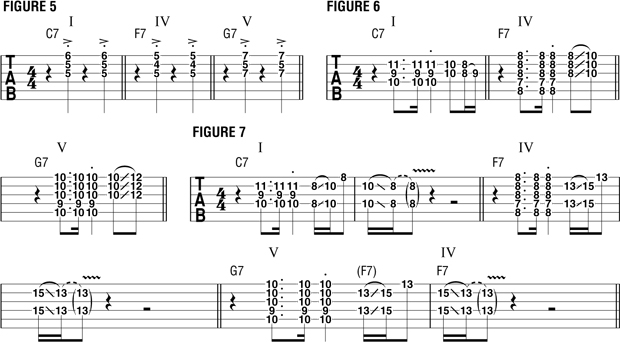

Soul blues grooves are built around syncopated bass/drum patterns, a strong backbeat (snare accents on beats two and four) and funky one- or two-bar bass riffs. Standard rhythm guitar options include doubling the bass line (FIGURE 1 is typical of the style), augmenting the line with chord accents (FIGURE 2) and combining the two (FIGURE 3 illustrates a 12-bar arrangement). A simple line like this can also be spiced up by harmonizing it in thirds, as demonstrated in FIGURE 4. Plug each chord into the 12-bar progression. For a second guitar, the can’t-fail rhythm part is “chicks”—sharp, percussive chords—synced with the backbeat (FIGURE 5).

Another effective rhythm guitar approach is to devise a pattern that “answers” the bass line by filling in the rhythmic spaces. FIGURE 6, for example, follows the bass rhythm in the first half of the bar and then answers it with a chord figure in the second half. FIGURE 7 is a sparser variation based on sixth intervals, a sound favored by Booker T. & the MGs guitarist Steve Cropper.

Devising fills that effectively complement funky bass/drum patterns while leaving room for vocals and solos is something of an art, but the general rule is to keep it simple and punchy. As for soloing, there’s no trick—just let the rhythm guide you, and play the natural blues.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!