“He was told early in his career that his playing was too loud, too strident and outside the accepted norms of the day”: Buddy Guy influenced Clapton, Page, Hendrix and countless others – here’s what you can learn from blues guitar’s greatest showman

No-one plays the blues like Buddy Guy – but that doesn't stop us trying. We look at four ways the blues icon approaches his solos. Warning: it's going to get fiery

Buddy Guy is the pioneer who influenced Hendrix, Clapton, Page and Beck among others. His fiery playing (and equally impassioned vocals) remain as exciting today as ever.

Like Eric Clapton, he was told early in his career that his playing was too loud, too strident and outside the accepted norms of the day. This necessitated him largely pausing his solo career after 1967’s I Left My Blues In San Francisco to become a sideman for artists such as Muddy Waters, Sonny Boy Williamson and Little Walter, supplementing his income with club dates and working as a tow truck driver.

Thankfully, he hung on in there, and though his recorded output was minimal during the 1970s, his career really took off in the late ’80s and early ’90s and hasn’t slowed down since.

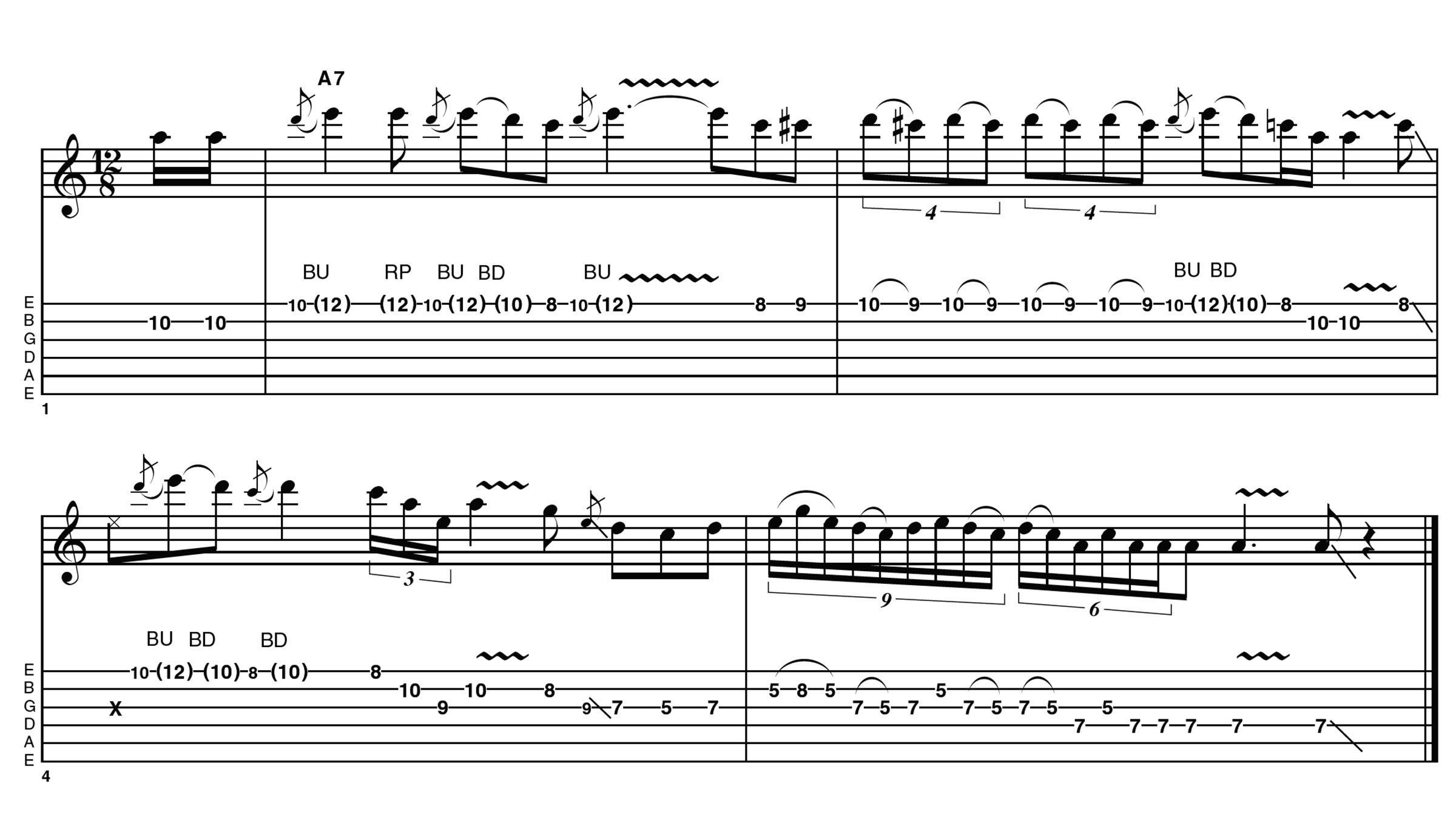

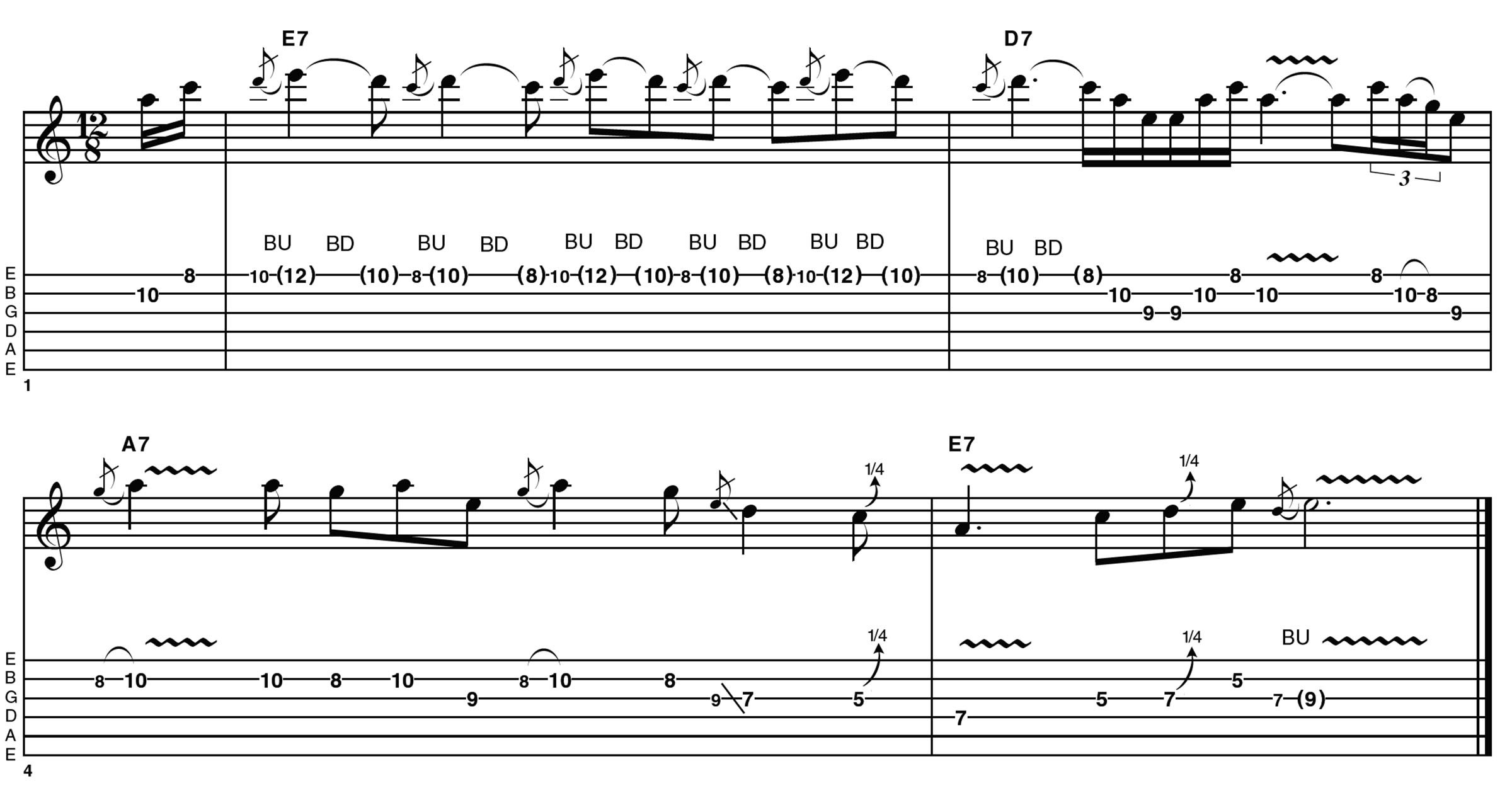

The focus in these examples isn’t to perfectly imitate Buddy’s playing because this would be an impossible task. Neither is it on extended scales, arpeggios or advanced music theory: everything is played within a few frets, using shapes 1 and 2 of the A minor pentatonic scale, with hardly any additions.

There is complexity in Buddy’s playing, but this is to be found more in the phrasing, particularly the rhythmic groupings. Longer held notes are deliberately contrasted with rapid-fire triplet bursts, taking pause between phrases for the vocals.

Obviously, demonstrating the silence between phrases would be of dubious benefit in this context, so please bear this in mind.

The examples were recorded separately but with the intention that they could be heard and/or played together as a continuous solo. I’m using the neck and middle single coils together with a fairly hard, driven sound. A bit of reverb is always nice, but the idea is to squeeze a lot out of a little. Enjoy and see you next time!

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Example 1

In this opening phrase, there’s an instant switch from shape 1 to shape 2 of the A minor pentatonic scale. You’ll notice that the backing track is very major in its tonality, but blues often makes a feature of combining the two, or of treading a fine line between them.

There’s plenty of repetition here, with no hurry to burst into flurries of notes. There will be a little of that later, but this phrase is key to establishing the mood.

Example 2

Staying squarely within A minor pentatonic shape 1, this example starts out in a similar fashion to Example 1 but then unleashes some faster triplets going into bar 2. The importance of absolute accuracy in this is debatable.

While we don’t want to drop the ball completely, being too slick seems to lose the quality we’re after. Jimmy Page’s playing in I Can’t Quit You Baby is another example of this quality. Have a play and see what you think.

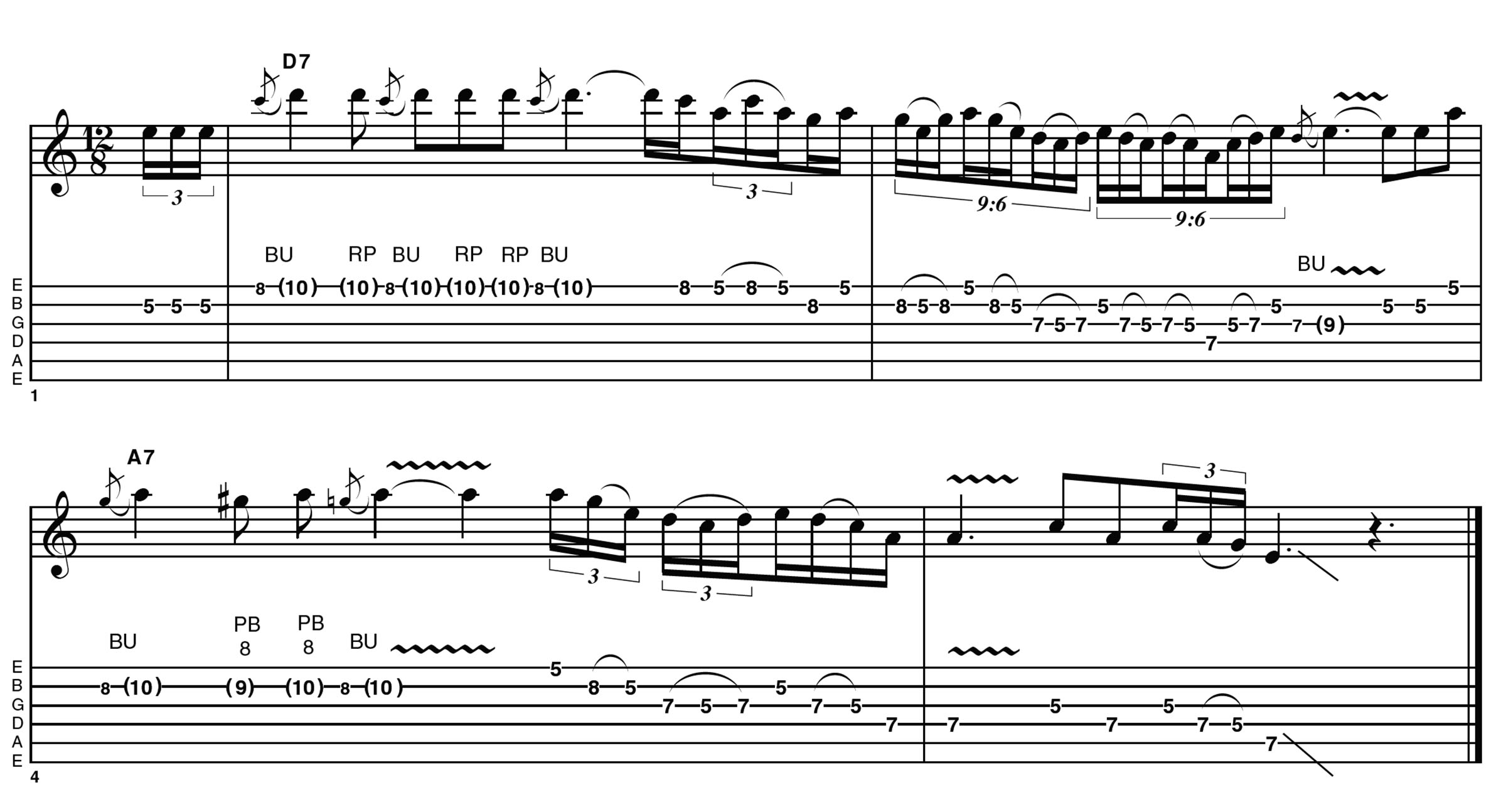

Example 3

Back to shape 2 to start with some repeated bends. Switching position for these is actually quite tricky, so after all that talk earlier of not being too accurate, this may be a surprise.

We stick with a similar vocabulary and rhythmic groupings until the end of bar 3, when we slide down towards shape 1.

Here’s an example of how not to be too slick: my first instinct was to go back and not play that A over the final E chord in bar 4 but spontaneity would have been lost.

Example 4

This is an alternate take over the first four bars, pulling out a few more stops. Note the C# and C natural playing off each other in bars 1 and 2. This is a clear example of the major/minor interplay we see so often in the blues.

The rest of this example reimagines some of the ideas we’ve already seen in a slightly different context, showing that there is always more than one way to deliver them.

Hear it here

Buddy Guy – Left My Blues in San Francisco

Buddy’s debut solo album was released in 1967. This is much more of a ‘soul’ sound than the rip-roaring blues Buddy became known for later in his career, but even though the guitar tones are cleaner and the arrangements more brass-heavy, the impassioned vocals and distinctive guitar are recognisable on Crazy Love.

I Suffer With The Blues features some edgier guitar, and Buddy’s Groove manages to capture the vibe of a live performance over a great rhythm section.

Buddy Guy – Damn Right, I’ve Got the Blues

We’re skipping forward in time to 1991 and the album that finally established Buddy as a major recording artist in his own right. The arrangements are more rock than soul, and though there is brass, this more often forms part of the backdrop to Buddy’s guitar, rather than sharing centre stage.

You may have noticed that the examples/solo were somewhat inspired by Buddy’s playing on the title track. Elsewhere, check out the gospel 3/4 time of Early In The Morning and the laid-back phrasing of Black Night.

Buddy Guy – The Blues Don’t Lie

Buddy’s most recent release from 2022, the 16-track album The Blues Don’t Lie, has a polished rock sound, but his guitar and vocals retain the raw edge he has become so known for.

Check out the nimble soloing and wah-wah on opening track I Let My Guitar Do The Talking, and the more delicate touches on the autobiographical title track, which is more akin to that first album back in 1967. Well Enough Alone features hard-rock riffing with Buddy’s guitar slicing through the mix.

- This article first appeared in Guitarist. Subscribe and save.

As well as a longtime contributor to Guitarist and Guitar Techniques, Richard is Tony Hadley’s longstanding guitarist, and has worked with everyone from Roger Daltrey to Ronan Keating.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.