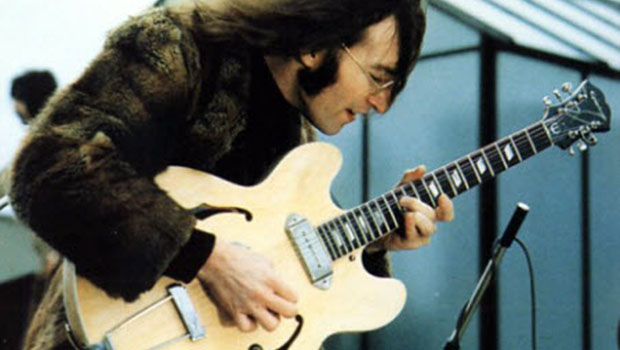

John Lennon's 10 Greatest Guitar Moments with The Beatles

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

XX. Long Tall Sally

Long Tall Sally (EP) (1964)

50. Across the Universe

Let It Be… Naked (2003)

John Lennon considered the Beatles’ recording of this 1967 composition “a lousy track of a great song,” dismissing even his own work on it.

He was too hard on himself: his imperfect acoustic guitar work and vocal delivery effectively work in service of the song’s sincere devotional message, though overdubs of strings, background vocals and electric guitar obscured the delicacy and intimacy of his performance.

The release of Let It Be… Naked in 2003 set the record straight, offering a bare-bones acoustic mix of the track that even Lennon might have approved of.

46. For You Blue

Let It Be (1970)

Written by Harrison, this seemingly straightforward blues workout in D stands out as a bouncy oddball in the Beatles’ catalog.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Not only is it one of the band’s few forays into 12-bar-blues territory; it also finds Lennon stepping into the uncommon role of lead guitarist, supplying a spirited solo and fills on a Hofner Hawaiian Standard lap-steel guitar in open D tuning.

To make things even weirder, he uses a shotgun shell as a slide. In addition, there’s no bass on the recording; McCartney performed on piano and the song received no overdubs.

42. The Ballad of John and Yoko

1967–1970 (1973)

In this 1969 musical telling of Lennon and Yoko Ono’s wedding and honeymoon, Lennon’s acoustic strumming sets up the song’s infectious rhythm, while his electric guitar fills play call-and-response with his vocals.

The track was written and recorded in April of that year, fresh off the sessions for Let It Be, in which the group attempted to get back to their rock and roll roots. That might have inspired Lennon’s musical direction with this track, which he closes with an electric guitar riff reminiscent of Dorsey Burnett’s “Lonesome Tears in My Eyes,” which the Beatles covered early in their career.

41. Yer Blues

The Beatles (1968)

Lennon wrote this 1968 song as a rude sendup of the electric blues boom that had taken London by storm, but the suicidal feelings he expresses were a sincere articulation of how he felt trapped both in his unhappy first marriage and in the Beatles.

Likewise, his primitive two-note solo could be regarded as mocking disdain for the genre’s slick white imitators, but he plays the riff until it’s as raw as his emotions. He would pursue this protopunk style of guitar playing further on his 1970 solo debut, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band.

39. Dear Prudence

The Beatles (1968)

This 1968 composition is arguably one of Lennon’s greatest achievements as a guitarist and demonstrates his development at the time into a bona fide acoustic fingerpicker.

Having recently learned a basic eighth-note Travis-picking-like pattern from British pop star Donovan, Lennon put the newly learned pattern to great use in compositions like “Julia,” “Happiness Is a Warm Gun” and, most brilliantly, “Dear Prudence,” applying it to an ethereal modal chord progression he invented, which he performed in drop-D tuning (low to high, D A D G B E), using the two open D strings (the fourth and sixth) as ringing drones, or pedal tones throughout the majority of the song.

The thumb-picking pattern goes fifth string, fourth string, sixth string, fourth string and repeats consistently through the changing chords, interrupted briefly at the end of each verse.

34. Girl

Rubber Soul (1965)

Lennon conjures up this song’s dreamy, Gypsy-like reverie by capoing his Gibson J-160E at the eighth fret, making the guitar sound similar to a mandola.

Harrison furthers the vibe on the third verse, playing a mandolin-like melody on Lennon’s Framus Hootenanny 12-string acoustic. But the crowning touch comes at the coda, when a third acoustic guitar enters, playing a Greek-style melody that’s plucked at the bridge with sharp strokes, making it sound like a bouzouki and further emphasizing the song’s smoky, old-world aura.

The British group the Hollies would copy the effect on their hit “Bus Stop,” recorded at Abbey Road some six months later.

16. All My Loving

With the Beatles (1963)

For this pop song’s thumping, quasi–jump blues, rockabilly-style groove, Harrison crafted a convincingly authentic Chet Atkins/Carl Perkins–like solo break that clearly demonstrates his familiarity with that Fifties Nashville style of electric guitar soloing.

Employing hybrid picking (pick-and-fingers technique), the guitarist acknowledges and gravitates toward the underlying chords in his melodic phrases, employing country-style “walk-ups” and “walk-downs” and plucking double-stops (pairs of notes) to sweetly and effectively outline the chord changes with a pleasing thematic continuity.

- Lennon contributed an energetic rhythm guitar part, one that he later expressed being rather proud of, which propels the groove with tireless waves of triplet chord strums, similar to those heard in the Crystals’ song “Da Doo Ron Ron.”

09. I Want You (She’s So Heavy)

Abbey Road (1969)

John Lennon was composing some of the heaviest rock and roll in the Beatles’ catalog in 1969, and this song—true to its title—is among the most crushing, thanks to an abundance of doubled and overdubbed guitar lines that give it some serious sonic heft.

Lennon wrote the song for Yoko Ono, with whom he was newly in love, and the result is a spellbinding exercise in obsessive repetition, from its lyrics—consisting almost entirely of the title and roughly five other words—to the ominous guitar lines that recur throughout it.

Clocking in at 7:47, the song is also one of the Beatles’ longest.

And although it consists of nothing more than a verse and a chorus repeated several times, it is rhythmically one of their most intricate tunes, switching between 12/8 meter and 4/4 rhythms alternately played bluesy and with a double-time rock beat. Few other artists could have made so much with so little.

01. “The End”

Abbey Road (1969)

A song called “The End” might seem an ironic place to start a list of the Beatles’ 50 greatest guitar moments. But the round-robin solos that bring the track to its exhilarating peak are without question the group’s most powerful statement expressed through the guitar.

Here, for a mere 35 seconds, three childhood friends and longtime band mates—Paul McCartney, George Harrison and John Lennon—trade licks on a song that represents, musically and literally, the Beatles’ last stand as a rock group before they broke up the following year. “The End” is the grand finale in the medley of tunes that make up much of Abbey Road’s second side.

As such, it’s designed to deliver maximum emotional punch, and it succeeds completely, thanks in great part to the sound of McCartney, Harrison and Lennon rocking out on their guitars, as they did in their first, embryonic attempts to make rock and roll some 12 years earlier.

“They knew they had to finish the album up with something big,” recalls Geoff Emerick, the famed Abbey Road engineer who worked on the 1969 album.

“Originally, they couldn’t decide if John or George would do the solo, and eventually they said, ‘Well, let’s have the three of us do the solo.’ It was Paul’s song, so Paul was gonna go first, followed by George and John. It was unbelievable. And it was all done live and in one take.”

Much of the song’s power comes from the sense that the Beatles are making up their solos spontaneously, playing off one another in the heat of the moment. As it turns out, that’s partly accurate.

“They’d worked out roughly what they were going to do for the solos,” Emerick says, “but the execution of it was just superb. It sounds spontaneous. When they were done, everyone beamed. I think in their minds they went back to their youths and those great memories of working together.”