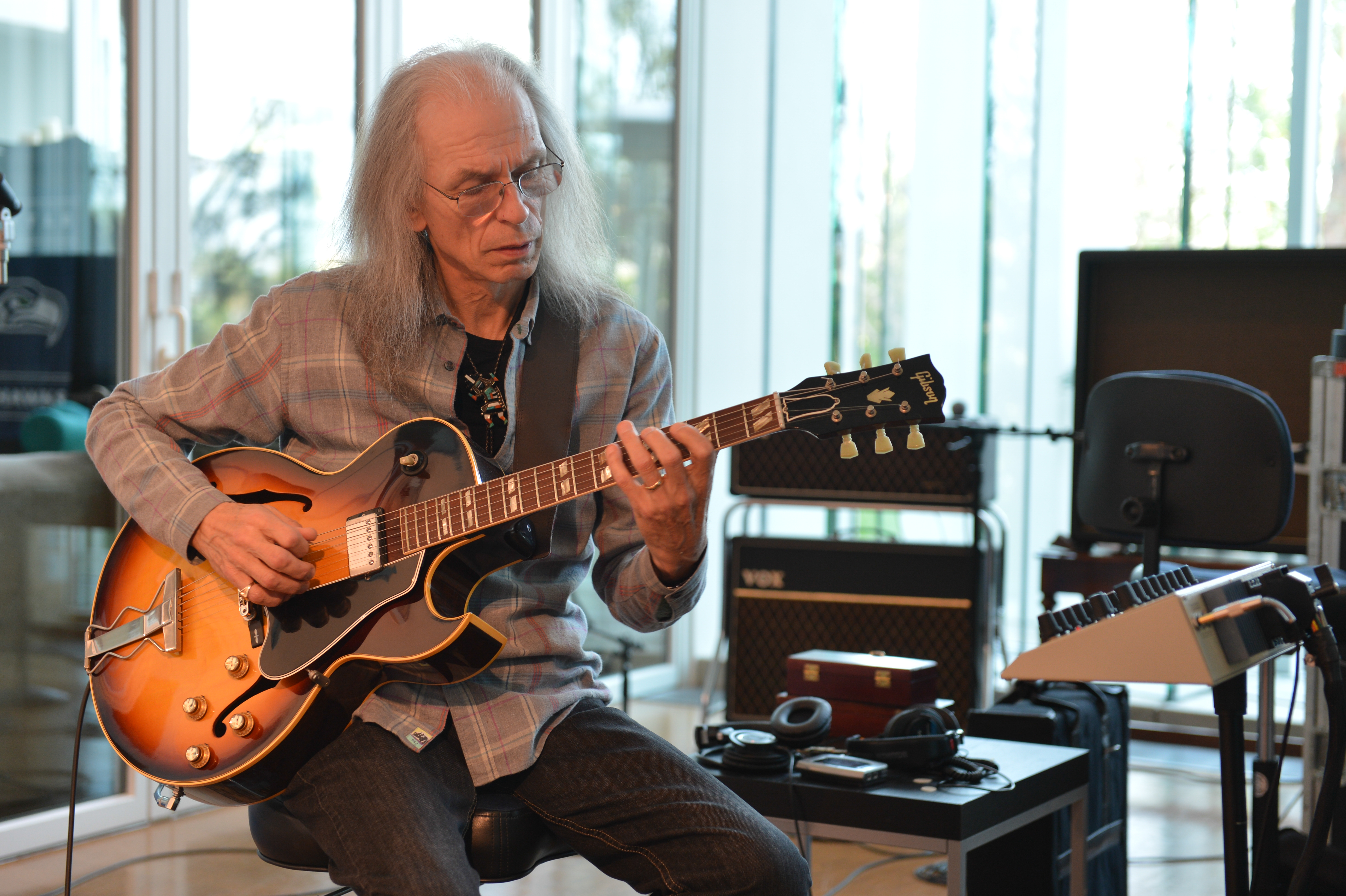

Yes Guitarist Steve Howe Discusses the Making of 'Fragile' and 'Close to the Edge'

“Somebody called me the granddaddy of prog-rock,” Steve Howe says with a laugh.

“I’m not ashamed to be called that. But the thing that matters most to me is musicality. I don’t think prog is all about technical playing. Much more important are your musical ideas. What choices and decisions are you making in the music? If that’s still an intelligent force within the music, then I like being considered a part of prog.”

More than just a part of progressive rock, Howe is one of the music’s great originators.

From the moment he joined Yes in 1970, he staked out a bold and vast territorial range for the guitar in a musical form often dominated by keyboard virtuosos like Keith Emerson and his former Yes bandmate Rick Wakeman. What those guys needed banks of pianos, organs and synthesizers to achieve Howe could often attain with just six strings and a boundless imagination.

His contribution, moreover, transcends prog-rock or any single musical genre. Steve Howe is one of the most distinctive and original guitarists in all of rock, a brilliant musical colorist whose evocative volume pedal swells and echoey textures possess all the subtle and complex expressiveness of the human voice itself. Howe’s palette has always been incredibly broad, drafting everything from classical and flamenco fire to psychedelic expansiveness to jazzy archtop electric abstraction into the rock guitar vocabulary.

At age 67, he’s still in top form, as can be clearly heard on the brand new Yes album, Heaven & Earth. On the disc, Howe is joined by longtime Yes members bassist Chris Squire, drummer Alan White and keyboardist Geoff Downs, who has been an on-and-off Yes-man since 1980.

On vocals is the group’s newest member, Jon Davison, who joined in 2012 and does a superb job of channeling the dulcet melodicism of original Yes vocalist Jon Anderson. Davison even shares Anderson’s spiritual perspective on lyric writing and fondness of Indian guru Paramahansa Yogananda.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

While some tracks on Heaven & Earth evoke the prog symphonic majesty of Yes’ Seventies heyday, others skew in a lighter pop direction more in keeping with radio-friendly Eighties Yes recordings, such as their 90125 album. But in working with legendary producer Roy Thomas Baker (Queen, the Cars, Smashing Pumpkins), on Heaven & Earth, Howe had one supreme mandate.

“I told Roy, ‘It’s gotta be Yes.’ ”

The prominent presence of Howe’s guitar work on the album is a sterling guarantee that the disc does indeed sound like Yes. Howe’s inventive melody lines and otherworldly textures are woven deep into the polychromatic musical fabric. Never an overtly flash player, Howe will nonetheless sometimes conclude a tuneful guitar passage with a brief burst of sheer incandescent brilliance. The effortlessness with which he executes these dazzling little interludes offers understated testimony to his mastery of his instrument.

“I don’t think guitarists should concentrate on being guitarists,” he says. “They should concentrate on being musicians. Being a guitarist can be a dangerous thing if you just want to race off and steal the show all the time on bended knees with your tiddly tiddly tiddly. I think that’s pretty dead in the water. I daresay most people agree.”

Once famed for bringing a vast arsenal of guitars with him onstage and in the studio, Howe has taken a more streamlined approach in recent years. His rig is based largely around his Line 6 Variax guitar and Line 6 HD500/Bogner DT50 digital modeling amp and pedal board, which allow him to cover a wide range of traditional guitar and amp tones.

“I think the Variax is one of the most overlooked instruments in the guitar universe,” he says. “The first time I saw it, I knew it was made for me. I like affordable guitars that can make lots of sounds and textures. I’ve got to tell you, the Strat, ’58 Les Paul and [Gibson] ES-175 models, in particular, are sensational on the Variax. Okay, it doesn’t feel like a Les Paul. But when you plug it in and it sounds like one, what’s the problem?”

Howe does augment this digital setup with several “real” guitars in his live rig, however, all of which made it into the studio for the Heaven & Earth sessions. These include his mid-Eighties red Fender Stratocaster; a 1955 Fender Telecaster which he has modified with a humbucker in the neck position, six-saddle bridge and Gibson-style toggle switch; a Martin MC-38 Steve Howe signature model acoustic; a Fender dual-neck steel guitar; and a Gibson Steve Howe signature model ES-175 electric archtop.

“That one is actually Number One—the first-ever Steve Howe production model 175,” he says. “And I added a third pickup to it, because at the time I was using it cover the sound of the [Gibson] ES-5 Switchmaster that I used on Yes’ Fragile album.”

This signature model 175 is based on Howe’s 1964 ES-175D, his first serious electric guitar, purchased new when he was just 17 and an instrument with which he has been closely associated ever since. These days he uses the guitar only in the U.K. where he lives, “because the airlines have been such an effing pain in the butt over the years,” he says. “But I have actually got a ’63 175 as well, which a friend of mine in Fort Wayne [Indiana] found for me. That was there with me in the studio as well.”

Another key instrument for Howe onstage and in the studio is his guitarra portuguesa, or Portuguese guitar. Heard on the track “To Ascend” from Heaven & Earth, it is also featured prominently on classic Yes tracks like “Your Move/All Good People” and “The Preacher The Teacher” and “Wonderous Stories.” Strung in six double-string courses, the instrument is tuned unconventionally by Howe: [low to high] E B E B E Ab.

“That one came from Spain,” he says, “My sister bought it for me when I was a kid. It has a slightly ringy, sitarish kind of sound that I really like. It has become a real identity thing with me.”

To this array of instruments from his live rig, Howe added a few more items during sessions for Heaven & Earth. “The only extra guitar was a Steinberger GMT that I really like,” he says. “And the studio had some really nice Marshall and Vox amps that I used. I also rented a Fender Deluxe that was customized by a good friend of mine, Rick Coberly.”

So while Howe wasn’t exactly lacking for guitars and amps while making the album, the setup was minimal compared with the days of Seventies prog-rock opulence. “Usually I would do a whole setup for an album, which could be anything from 15 to 30 guitars—a bit extravagant,” Howe says, with a laugh. “Plus various amps—things I liked and had tried out. The whole fiddly process. But this time, we really didn’t have time for that. Nobody did in their own departments. Basically, we wanted to streamline the whole process.”

Howe’s relatively compact live rig will also serve him in good stead on the current Yes tour, which will feature live performances by the band of two classic Yes albums, Fragile and Close to the Edge, in their entirety. Released in 1971, Fragile was Yes’ breakthrough record. It featured what for many is the classic Yes lineup: Anderson, Howe, Squire, Wakeman and drummer extraordinaire Bill Bruford. But what really put the album across at the time was its lead track and hit single “Roundabout,” a perfect amalgam of melodic accessibility, driving rock, deft arrangement and superior musicianship.

“We’ve been playing ‘Roundabout’ and ‘Heart of the Sunrise’ from Fragile for years,” Howe says. “But in performing the entire album live, I really wanted to revisit the way we actually did those songs on the record—to capture the understatement, the subtleties and the playing down. Because playing onstage is often—too often for my liking—all about playing up. But I really like the subtleties and less expected moments of tranquility and gentleness. I think people sometimes forget that that’s the key to Yes. There’s no bash and crash about Yes.”

“Roundabout” is one of many classic Yes songs that Howe wrote in collaboration with Jon Anderson. “Jon and I were in a hotel room up in Scotland when we started writing that song,” Howe recalls. “We seemed to find a lot of time to do that in the Seventies. We had a private plane. We got to places. People sat by the pool. And Jon and I were in this hotel room, kind of going, ‘Well, what have you got that’s a bit like this?’ We used to quiz one another like that. We did those exchanges in our music, and lyrically as well. This was the era of cassettes, and I’ve still got all of them—Jon and me fooling around in hotel rooms.

"And with ‘Roundabout,’ we had all these bits of music, tentative moments. I was big on intros back then, and the classical guitar intro I came up with for ‘Roundabout’ was really one of the most signature things. And I believe I thought of the backward piano [also in the intro], but I won’t lay 100 percent claim to that, in case I’m wrong. But basically the song just kept developing. Jon and I presented as much as we had to the band, and the band did a fair amount of input and arrangement. What Yes were brilliant at, even before I joined, was arranging skills.”

Another key feature of Fragile were its solo tracks, written and performed by each of the five band members. Howe’s contribution was “Mood for a Day,” a solo piece he performed on a Conde classical guitar and which toggles neatly between baroque decorum and flamenco passion.

“It was Bill Bruford who thought of the concept of doing individual tracks, not to mention the album title Fragile,” Howe recalls. “But his original idea wasn’t that each guy should do a completely solo track, the way I did mine and Rick Wakeman did his. Bill’s concept was more like he did with his own track, ‘Five Per Cent for Nothing,’ where the group were utilized at his command—like, ‘You play this and you play that.’ I think we could make up our own notes, but we had to play his beats, which was a marvelous way of doing it. I was really excited about doing that live, but other people in the group were like, ‘Are we really gonna do this?’ I think the guitar part is one of the easiest parts in it. But there was a fair amount of struggling with some of the other parts, because they have to mix together. Bill wasn’t the kind of drummer you could just busk along to.”

Howe’s main electric guitar for Fragile was the aforementioned Gibson ES-5 Switchmaster, which he recalls playing through a Dual Showman amp. “In 1969, I toured with Delaney & Bonnie as guitarist for the opening act, P.P. Arnold,” Howe narrates. “On that tour, both Eric Clapton and George Harrison were playing with Delaney & Bonnie, and they both had Dual Showmen. So when I joined Yes a year later, I was hell-bent to buy a Dual Showman. And I did.”

Yes’ 1972 masterpiece, Close to the Edge, was the triumphant follow-up to Fragile. While capitalizing on all the strengths of Fragile, Close to the Edge also took Yes into a new compositional dimension. Occupying all of side one on the original vinyl release, the album’s title track is a tour de force of brilliant, recurring melodic and lyrical themes that overlap in myriad permutations—transposed, superimposed, reharmonized, contrapuctualized and melded into one of progressive rock’s proudest and finest moments. “Close to the Edge” is another outstanding compositional collaboration between Anderson and Howe.

“Jon was more competent than me lyrically,” Howe says. “But I wound up writing lyrics for ‘Close to the Edge,’ and our next album Tales from Topographic Oceans. My stuff was more lateral, more earthbound, as opposed to his skybound stuff. The lyrical phrase ‘Close to the edge, down by the river’ was originally about the River Thames! But Jon converted that into the river of life, which was a wonderful thing.” As with “Roundabout,” Howe and Anderson began by amassing the musical fragments that would eventually go to making up “Close to the Edge.”

“Jon and I put together a lot of the shape of that song. We’d been working live with the Mahavishnu Orchestra at the time, and it might have been Jon who said to me, ‘Why don’t we start this with improvisation? That would be really scary.’ Normally you start off with something you can grasp—an intro or a hook. But we inspired Yes to go into this improvisation. All I had on guitar was that octave jumping two-note phrase you hear on the record. But that was enough to kick off an improvisation. After that it was purely freeform. Although we did have those stops arranged. [i.e., climactic moments that give way to a single a cappella chord in vocal harmony.] I can only look back in amazement that we were able to do some of that. But we did. We didn’t always count everything out. It was almost like we could remember things that were quite complicated. So that intro then spawned the whole idea of a thematic approach—the musical themes that come in and out of the track.“Jon and I really had a certain magic going on at that time,” Howe continues. “That level of collaboration ended after we wrote ‘Awaken’ [from 1977’s Going for the One], which is another really epic piece. We did some good work after that, like “Bring Me to the Power” on Keys to Ascension 2 [1997], some songs on The Ladder [1999] and a few on Magnification [2001]. But I think that greatest time was ‘Roundabout’ through ‘Awaken.’ ” Howe’s main electric guitar for Close to the Edge was a Gibson ES-345 stereo model. He is one of the few rock guitarists to fully exploit the atmospheric potential of stereo guitar. Each of the 345’s two pickups would be routed to a separate amp with a separate delay line and volume pedal for each. “A lot of the panning I did live with my feet between the two pickups,” he explains. “I had a volume pedal for each pickup and panned them in opposite ways. When one went down, the other one went up. I had a lot of fun! You can hear it if you listen with headphones.” The volume pedal has always been a key element to Howe’s guitar approach. He’s used a variety of pedals down through the years, including Fender, Sho-Bud and Ernie Ball units. Since 2006, he’s employed the volume pedal on the Line 6 HD500 pedal board. “As soon as I got an electric guitar I also got a volume pedal,” he says. “And that really started my relationship with phrasing, effects and being able to alter the way a guitar sounds. And of course delays are also very important. The way you can play into a delay with a volume pedal is also a very exciting thing I developed. And then of course the fuzz box, wah and all kinds of guitar processing.” Close to the Edge was also Bill Bruford’s last album with Yes. He departed the band to join King Crimson not long after Close to the Edge was completed. “I see him as a quintessential Yes member,” Howe says. “And when he ran off from us to join Crimson, that was a really painful experience for me. Because I didn’t want him to go, not one bit. Yet what he proved to me is that a musician always has to follow his music. And I tend to do that. That’s why I left Asia a year or so back. Because I listened to myself and said, ‘I can’t do this now.’ And I’ve done that often in my career when I’ve made decisions. It’s good to remember that, no matter who the paymaster is, or what you’re going to lose, if you don’t follow the direction your music takes you in, then you’ll fall. You’ll lose much more than a few bucks.”In the years since Yes’ early Seventies classic run, Howe has kept up with old band mates like Bruford and Anderson through projects like Anderson, Wakeman, Bruford and Howe in the late Eighties/early Nineties. He’s currently planning to record a few of Bruford’s compositions on the next release by his side group, the Steve Howe Trio. Meanwhile, he still keeps an ear out for exciting new guitarists. “I really love Martin Taylor as a jazz guitarist,” he says. “He does everything I love. Wonderful guitarist. Wonderful technique. And yet he isn’t stifled by technique. By the time you’re a virtuoso, you don’t think along the lines of technique. Your technique is solid enough to enable you to do anything you want. Another guitarist I really admire is Flavio Sala, a young guitarist from Italy. He’s just over 30 now. "And he’s got all the classical repertoire under his belt, which is a huge goal to be at by your 30th birthday. But now he’s looking at music in a more general way, and not shy about it. I met him a few years ago. We recorded a track together, which we haven’t released yet. But whenever I see a guitarist, I can’t help but want to understand more about, Where’s this guy at? What’s his repertoire? With a guy like Flavio I think, That’s a true international guitarist. And I think that’s the goal for all of us as players—to become an international guitarist.”

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.