1969 Telegram from Jimi Hendrix and Miles Davis: Can Paul McCartney Come Out to Play?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It's pretty well known that Jimi Hendrix was looking to branch out and make some major stylistic changes not long before his death in September 1970.

It's also pretty well known that Hendrix and trumpet master Miles Davis were making plans to work together in a new project.

What's not so well known is that the duo, plus jazz drummer Tony Williams, reached out to then-Beatle Paul McCartney, asking him to join them on bass.

On October 21, 1969, Hendrix, Davis and Williams sent a telegram to the office of the Beatles' Apple Records, seeking McCartney's last-minute participation.

"We are recording and LP together this weekend in NewYork [sic]," reads the typo-filled note, according to The Associated Press. "How about coming in to play bass stop call Alvan Douglas 212-5812212. Peace Jimi Hendrix Miles Davis Tony Williams."

Beatles aide Peter Brown responded the next day, telling the other members of the supergroup-that-never-was that McCartney was on vacation and wasn't expected back for two weeks. It's unclear if McCartney was aware of the note.

The telegram, a part of the Hard Rock Cafe's collection, was bought at an auction in 1995. But it has received more attention lately as a result of the March release of People, Hell and Angels, a collection of 12 previously unreleased Hendrix recordings.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"It's not something you hear about a lot," Hard Rock historian Jeff Nolan said of the telegram, now displayed at the Hard Rock Cafe in Prague. "Major Hendrix connoisseurs are aware of it. It would have been one of the most insane supergroups. These four cats certainly reinvented their instruments and the way they're perceived."

It's difficult to say what McCartney's reaction would have been had he known about the telegram (That's assuming Brown never mentioned it to McCartney). He was, after all, a Beatle at the time.

Of course, by late October 1969, John Lennon had already dabbled with life outside of the Beatles universe. He had performed with Eric Clapton and future Yes drummer Alan White in Toronto that September and released two experimental solo albums, Unfinished Music No. 2: Life with the Lions and The Wedding Album (which came out October 20, 1969, one day before the telegram was sent).

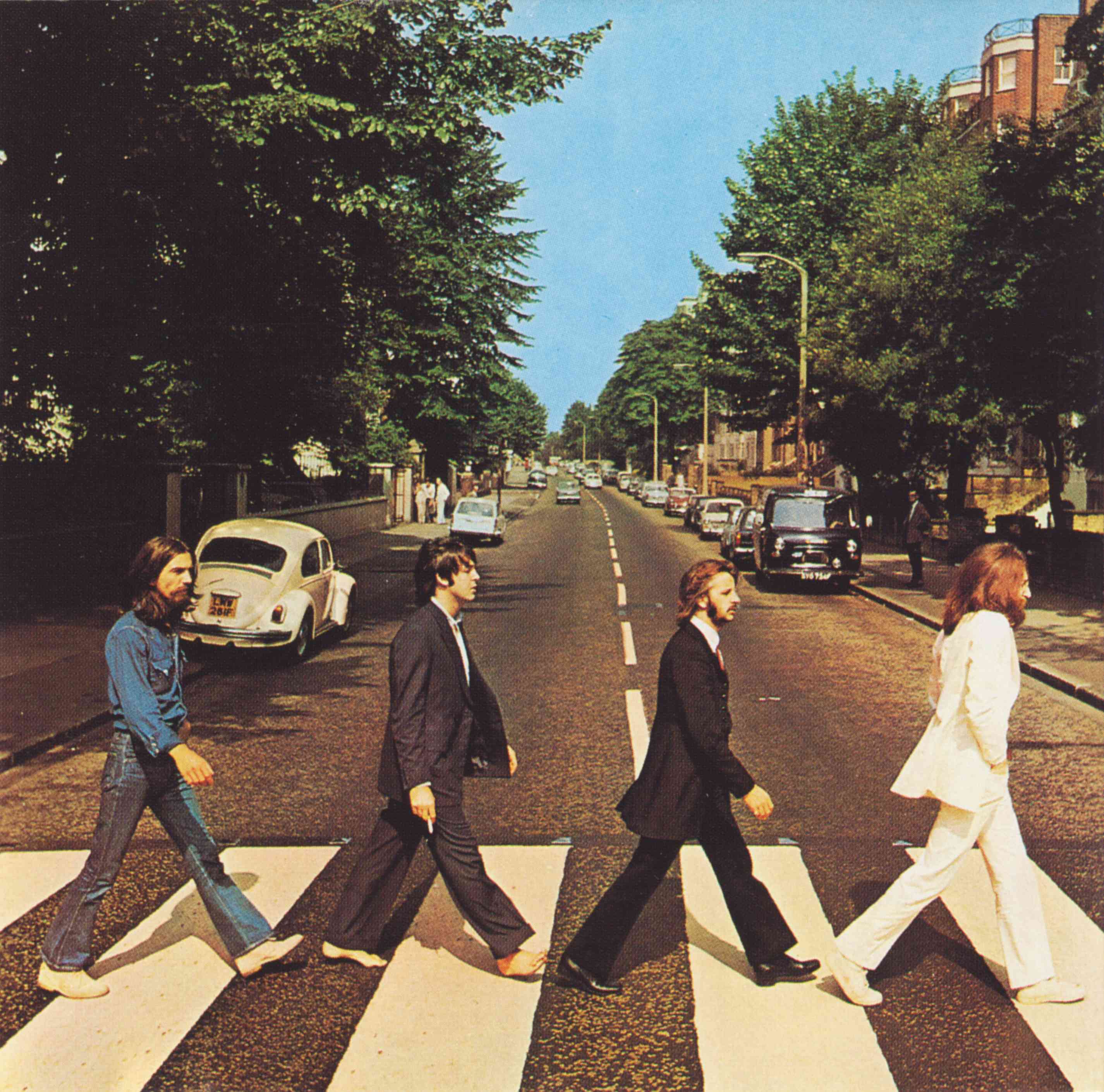

Meanwhile, George Harrison had already written and recorded a soundtrack album under his own name (1968's Wonderwall Music) and released an experimental album of his own (1969's Electronic Sound). He also was about to hit the road with Delaney & Bonnie and Friends.

In other words, the timing might've been perfect for McCartney to do some big-time branching out of his own. And who knows? Maybe Hendrix and McCartney might've had some "lefty" chemistry.

Damian is Editor-in-Chief of Guitar World magazine. In past lives, he was GW’s managing editor and online managing editor. He's written liner notes for major-label releases, including Stevie Ray Vaughan's 'The Complete Epic Recordings Collection' (Sony Legacy) and has interviewed everyone from Yngwie Malmsteen to Kevin Bacon (with a few memorable Eric Clapton chats thrown into the mix). Damian, a former member of Brooklyn's The Gas House Gorillas, was the sole guitarist in Mister Neutron, a trio that toured the U.S. and released three albums. He now plays in two NYC-area bands.