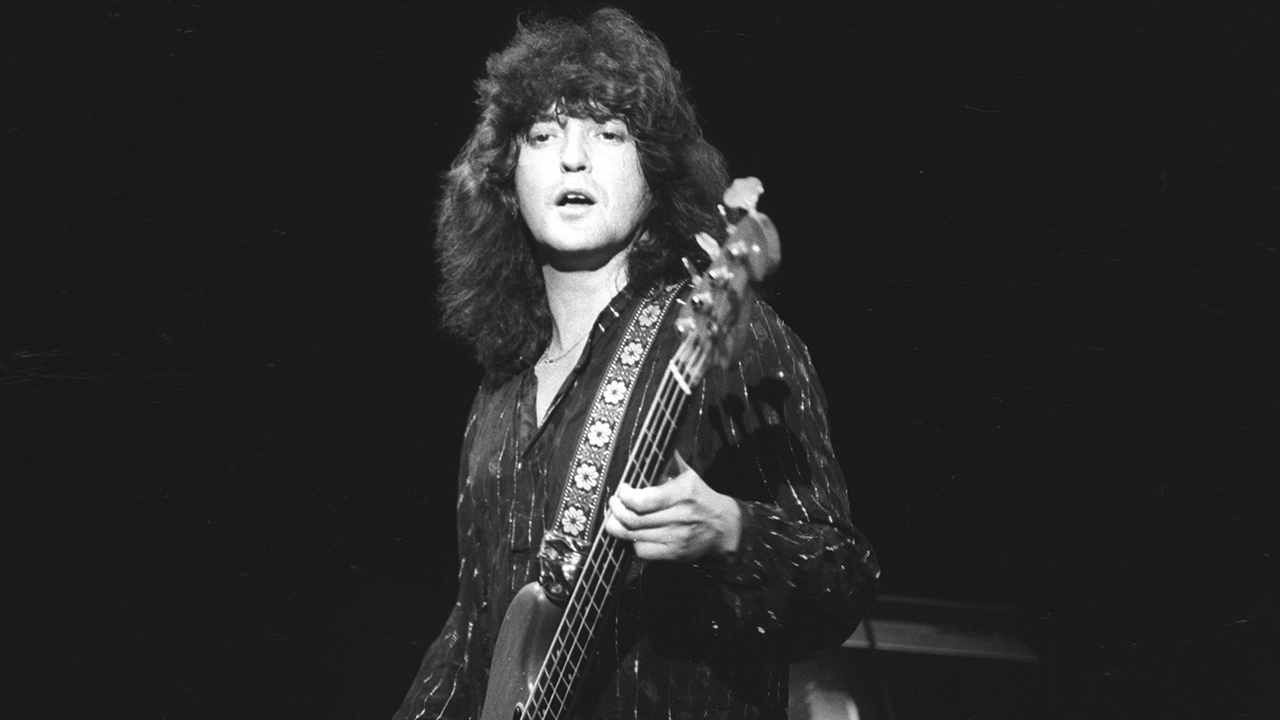

“People warned me, ‘If you work with Ritchie Blackmore, you could last 5 minutes. He could chew you up, spit you out. You could end up with nothing.’ So I did have to think about it”: Bob Daisley on Rainbow, Ozzy – and pairing up with Randy Rhoads

Born to be a bassist, he was warned against working with Rainbow and Sabbath alumni, but did it anyway. And his only regret is the ever-looming cloud over his celebrated work with Ozzy Osbourne

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Bob Daisley believes he was always destined to play bass. “When I saw an actual bass guitar in the flesh in front of me, it was just… wow,” he says. “I thought, ‘This is the heartbeat. This is the backbone. This is the pulse of the song.’ That’s all I wanted to do.”

With a recording career including records Rainbow’s Long Live ‘n’ Roll (1978), Ozzy Osbourne’s Blizzard of Ozz (1980) and Diary of a Madman (1981), along with loads of others, Daisley has made his mark. Few bassists could handle the temperament of Ritchie Blackmore or the whirlwind classical chops of Randy Rhoads – but he did just fine.

But a falling out with Ozzy and Sharon Osbourne overhangs his career. Nasty legal battles have him fighting not only for his money but also his legacy. He wishes things were simpler: “It’s not about ‘this one doing that’ or ‘these two did that’ – it was a chemistry and a coming together of energies.”

He argues: “It was meant to happen; it affected a lot of lives in a positive way. I’d like people to know that the music and the band were four people, not one. A band called The Blizzard of Ozz came along and did a couple of albums. Then, there was no more.”

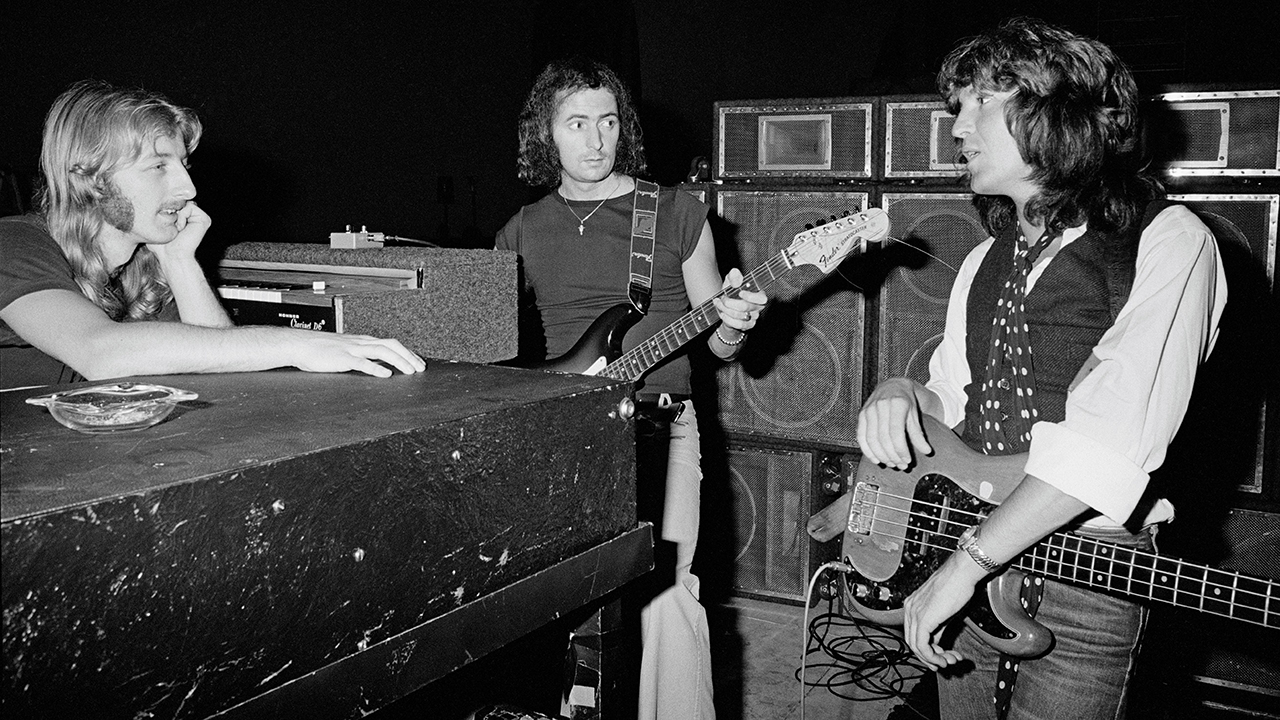

When you first joined Rainbow, what gear did you bring, and what approach did you use?

“I had a ’61 Fender Precision bass. That was my workhorse. It did most of the live stuff, most of the writing, most of the recording. It was just a great bass to play and had a great sound. I played with a pick and I was very precise with my playing.”

Was that what Ritchie was looking for?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Yes – he wanted someone who played with a pick. When I went for the audition, he put me through my paces. He got me to play certain things, and I had to keep on playing them for quite some time to see if I could cut it using the pick, playing eights, sixteenths, and that sort of thing. He was happy with what I did at the audition.”

What amps were you using?

“I used the gear that was supplied – Crown amps, which I didn’t really like, but I had to use them. It was their stage gear. I’d been using an Acoustic with two cabs, which sounded great. It had that lovely, warm, thumpy sound. But the stuff with Rainbow was supplied, so I used it.”

Ritchie is a notoriously tough guy to work with. Were you worried about getting on with him?

“What helped a little bit was that when I went for the audition, they’d already auditioned about 40 different bass players. They couldn’t find anyone they liked because you had to look the part and you also had to be the sort of person who got on with them all.

“We’re talking about Cozy Powell, Ronnie Jame Dio and Ritchie Blackmore here. At the end of my audition – I’d played for an hour and a half or so – they went off into an office somewhere and had a little chat. They came back out and said, ‘You’ve got the gig if you want it.’

“I didn’t do it to be cheeky, but I just said, ‘I’ll think about it.’ I was serious; I had my own band, Windowmaker, and people had warned me, ‘If you work with Ritchie, you could last five minutes. He could chew you up, spit you out. You could end up with nothing.’ So I did have to think about it.”

What led you to accept?

“I was doing a show at the Whisky with Widowmaker, and Ritchie and Cozy came along. I saw them before I went on, and he said, ‘Look, I’ll be at the Rainbow just up the road. Come see me after you’ve finished.’ I hadn’t joined the band at that point; I was still thinking about it. But Ritchie had sort of got it in his head that I’d accepted the offer.

“He stayed for the show and. At the end I went upstairs and a squabble broke out with Widowmaker. I thought, ‘Fuck this!’ I packed up my stuff and said, ‘I’m going to meet with Ritchie, and I’m joining Rainbow.’

“I stormed off. As I walked into the Rainbow, Ritchie was sitting at one of the tables. He started clapping, and I thought, ‘Wow… Ritchie doesn’t give praise easily.’ I thought, ‘I must have done something right.’ I told him, ‘Count me in.’ We started rehearsals the next day.”

What was the process of recording Long Live Rock ‘n’ Roll like?

“I just put my head down and got on with it. I tried to be as reliable and professional as I could be. I got on well with Ritchie; he could be – well, he knew what he wanted. He didn’t suffer fools gladly. He was also a very aware sort of person. Working with somebody like that, I actually enjoyed it. It was a good learning curve for me.”

Why did Ritchie replace you with Roger Glover?

“It kind of fizzled out. There was never any sort of definite phone call from Ritchie or management. We’d done a long US tour and a world tour that went through Europe, Scandinavia, Japan, and Canada. At the end we came home, and I was waiting to hear back, and nothing happened.”

You were talking to Ronnie about branching off with him, right?

“There was a point where I was waiting with Ronnie in a hotel lobby and he said, ‘If this band finishes, or if I’m not in the band, would you consider being in a band with me?’ I thought, ‘Does he know something that I don’t?’

“I said, ‘Well, yeah, of course. If this band’s not going, or I’m not in it, yeah, of course, I’d work with you, Ron.’ He must have had an inkling then of what was coming. I didn’t.”

Ronnie joined Sabbath not that long after. What happened there?

“I was in London and I got a call from Ronnie. He said, ‘It looks like the band’s not going to continue as it is. Would you be interested in putting a band together with me?’ I said, ‘Yeah, sure.’ He said, ‘Okay, don’t do anything. Hang in there. I’m going to start looking for a guitarist and line up record companies.’

People warned me against Ozzy… but I had a feeling of: ‘I’ve got to do this’

“A few weeks would pass, and he’d phone again and say, ‘I’m still working on it. Hang in there.’ After a while, I went for a stroll and bought a music paper. On the front page, it said, ‘Ronnie James Dio joins Black Sabbath.’ I thought, ‘Oh, thanks for telling me, Ron.’ But it was meant to happen as it did; everyone ended up in the best possible situation.”

Ironically, you joined Ozzy Osbourne’s solo group after Ronnie replaced him in Sabbath.

“Ozzy had just come back from LA been fired. People warned me against working with him because he didn’t have the best reputation. He’d been getting out of it, been unprofessional, unreliable and all the rest of it. But I had a feeling of: ‘I’ve got to do this.’

“He asked me to go up to his house and play, saying, ‘I’ve you got a first-class rail ticket.’ I jumped on a train in London, went up to Stratford, and Ozzy met me at the station. I went to his place and he had a guitarist and a drummer there.”

What did you think of them?

“They were okay guys and nice enough. But when Ozzy and I had a tea break, he said, ‘Well, what do you think?’ I really did like Ozzy, and we got on together, so I said, ‘I’d like to work with you, but I’m not sure about these other two guys.’

“I said, ‘They’re okay; but I don’t think they’re world-class.’ He said, ‘Oh, hang on a minute…’ He went into the rehearsal room and I heard him say, ‘Okay, fellas, you can pack up. It’s not working out. You can go home.’ That was them gone, dismissed.”

How did Randy Rhoads enter the picture?

“It was just me and Ozzy to start with. He told me about this young guitar player in LA who was a teacher at a music school. Ozzy said, ‘His name is Randy Rhoads.’ I sort of envisioned an older bloke with slippers, a cardigan and glasses! ‘I said, ‘Well, let’s get him over.’ Randy wouldn’t have been brought over if I hadn’t said ‘no’ to the other two guys.”

Ozzy was signed to Jet Records, and the story goes that Jet's founder said Randy was too young. Is that true?

“David Arden [son of Jet founder Don Arden] said, ‘No, he’s too young. He’s unknown. He’s got no reputation. He’s not a name.’ But eventually – and I remember his words – he said, ‘Against my better judgment, I will bring him over.’”

During one of the writing sessions Ozzy said, ‘I’d forgotten how much you had to do with writing the songs’

“Ozzy, Randy and I met up at Jet Records. It would have been towards the end of ’79. We all took the train up to Ozzy’s place in Stratford and played; after maybe 20 minutes or half an hour, Randy and I looked at each other at the same time and said the same thing: ‘I like the way you play.’ I knew right away that this would work; that this was good.”

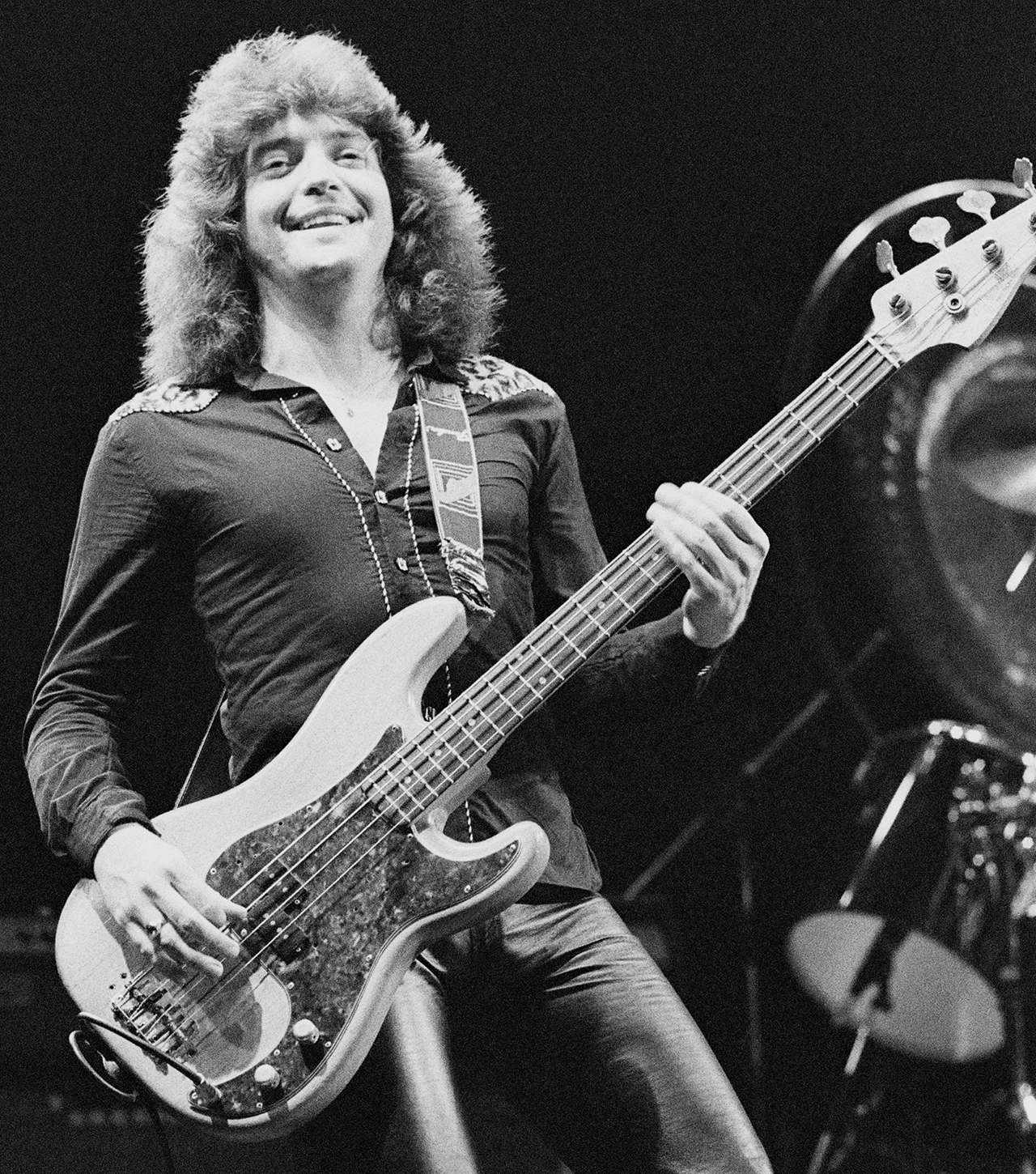

Once the sessions for the Blizzard of Ozz got rolling, was your gear different from your Rainbow days?

“I had my ’61 Precision and the Acoustic stack, which, for some reason, worked very well. We made lots of recordings of our rehearsals and writing sessions, which people now refer to as the ‘Holy Grail,’ because they were the reference tapes to those songs so we wouldn’t forget our parts.

“When we got to the studio, I wasn’t really happy with the sound I had, so I began using a Gibson EB-3 bass. It did the job, and the best match amp-wise was a Marshall. I said to Randy, ‘Can I use one of yours?’ So I used a Gibson EB-3 through one of Randy’s Marshall stacks, which was a 100-watt head driven hard by a 4x12 cab.”

For a long time, most people have assumed those recordings were strictly the brainchild of Ozzy and Randy. But your involvement was deep, right?

“They were trying to get rid of Lee Kerslake while we were on tour. I just couldn’t agree with something I thought was wrong – I said, ‘Look, it’s not broken. Stop trying to fix it.’ Eventually they got rid of both of us; but after six weeks, I got a call saying, ‘Will you come back?’

“I said, ‘I’ll record, I’ll co-write, but I’m not going on the road with you, and I’m not coming back into the band.’ I remember during one of the writing sessions for Bark at the Moon, Ozzy said, ‘I’d forgotten how much you had to do with writing the songs.’

“They’ve promoted the Ozzy/Randy-only thing and it’s inaccurate. People thought that because we used to come out at shows to Carmina Burana by Carl Orff, a classic piece, it was Randy’s idea because he was into classical. No, it was mine. I came up with that idea.

“I was pissed off with the whole thing, and I remember that someone at Jet Records phoned me up and said, ‘Sharon and Ozzy want to know what that piece of music that you used to come on stage to is called.’ I said, ‘Oh, well, tell them it’s called ‘Go Fuck Yourself,’ and I hung up.”

You composed and wrote the lyrics for songs like Crazy Train and Mr. Crowley.

“I wouldn’t want to take away from anyone, but I wouldn’t give anybody more praise than they earn. It took the three of us to do that – Ozzy’s vocal melodies were very important, and Randy’s guitar riffs and play were phenomenal.

It was certainly not the Ozzy/Randy show, which is how it’s been promoted. That’s not accurate at all

“It was brilliant and I loved it. But Randy wasn’t a lyricist, and neither was Ozzy; Geezer Butler used to write lyrics in Sabbath. So, between the three of us it was a joint effort. The pieces of the puzzle were as important as each other.”

What was it like working out parts with Randy?

“A lot of the songs were based on riffs that Randy had. We’d sit on chairs opposite each other; I’d make suggestions, we’d put things together, arrange things and try new bits. We’d take one piece out, put another in, and that would go on for weeks.

“Once we had the basic structure, Ozzy would sing his melody on it. It would start with words that came into his head that often didn’t make sense. I’d take the tape of us playing with Ozzy’s melody and phrasing and write lyrics to it.

“By the end of it all, you had proper songs. It was certainly not the Ozzy/Randy show, which is how it’s been promoted. That’s not accurate at all.”

It must have been painful when Randy passed in the plane crash.

“I was in Uriah Heep and we were flying to America. We landed in Houston, Texas, checked into our hotel and had a night off. As we were walking into a club we were supposed to play to check it out, a girl walked up to me and Lee, and said, ‘Aren’t you the guys from Ozzy’s band?’

“We said, ‘Yeah,’ and she said, ‘I think some of them got killed in a plane crash this morning.’ At first, I had thoughts of a commercial airliner going down, but then I was told it was just the pilot and Randy that had been killed in a small plane.

“That blew me away. I was speechless. Lee and I went back to the hotel and just drank toasts to Randy with all his favorite drinks. He used to drink these exotic drinks. We drank those to Randy and cried. It was awful.”

You’ve played with Ritchie Blackmore, Randy Rhoads, Jake E. Lee and Gary Moore. Who’s the greatest guitarist you’ve played with?

“They’re all different. I’ve been fortunate in working with so many wonderful players. Gary Moore, I’d say, is probably one of the best ever. Randy Rhoads was a phenomenal player. Ritchie Blackmore was just mind-blowing. He was superb. And Jake is a great, wonderful player.

I don’t like conflict. There was plenty of money to go around

“They were all perfect for what they were doing at the time. There is no best. I would never say, ‘I prefer this one over that one’ or, ‘One is better than the other.’”

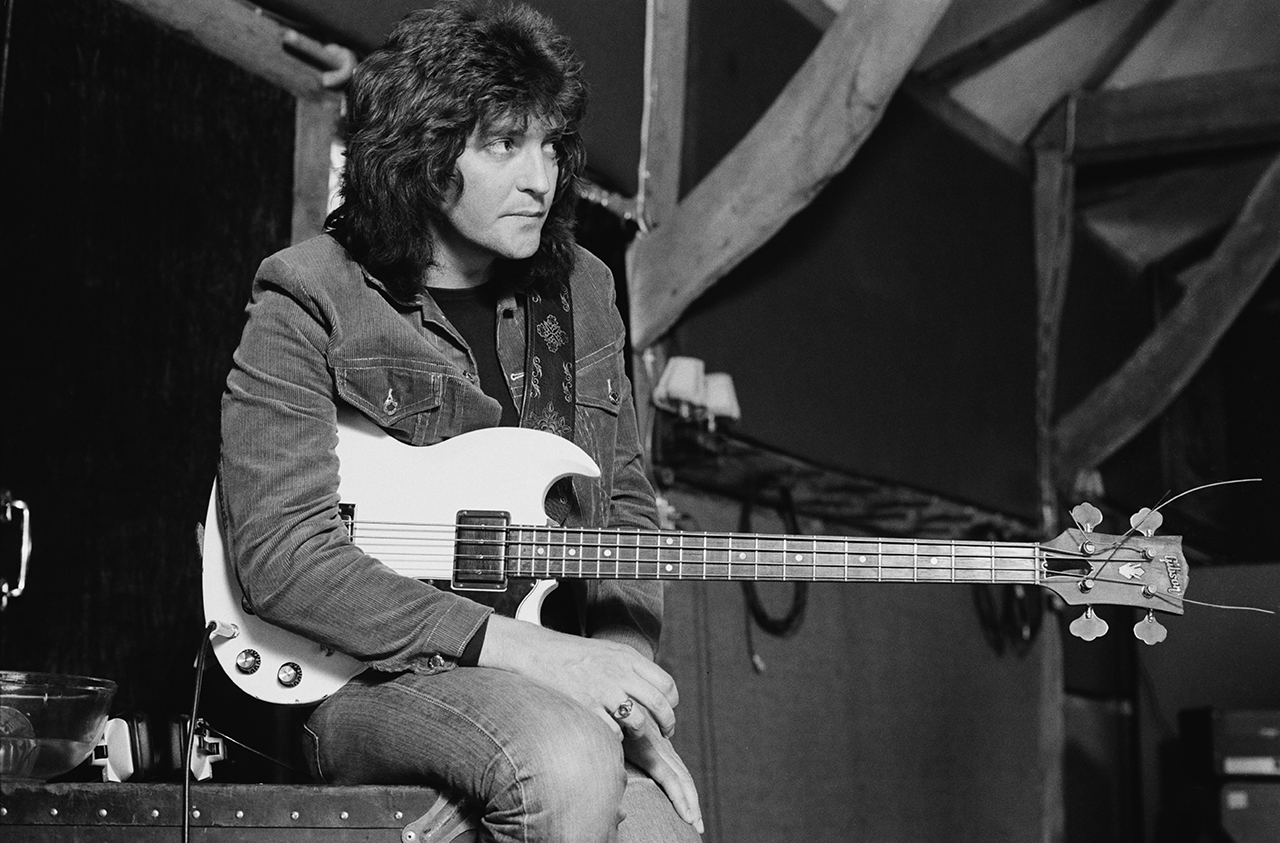

In recent years, you’ve fought hard to highlight your legacy within Ozzy’s early solo era.

“It’s been an uphill battle – and, I’ve always thought, an unnecessary one. It didn’t have to be like that. I had no personal vendetta with them. I don’t like any of it. I don’t like conflict. There was plenty of money to go around.

“I’ve always been one to accept that it is what it is, you know? It would be nice to think that if Randy hadn’t been killed, the original band would have made that third album. The word ‘if’ is such a little word with a big meaning. But all the conflict and lawsuits were unnecessary. It didn’t have to be like that.”

When was the last time you spoke with Ozzy?

“I haven’t had contact with Ozzy for many years. During the lawsuit, when I went to New York and we were doing depositions, I didn’t see Ozzy, but I saw Sharon. She said to me, ‘He misses you.’ I thought, ‘Well, that’s nice. I miss him, too.’

“We’d been mates. We could have created more good stuff together. But, you know, I just wish it hadn’t been like it was. We’re both getting old now. We’re both going to go out sooner than later. It would have been nice to go out on a brighter note. Such is life, I suppose.”

How do you hope to be remembered?

“I just hope I made a difference while I was here. That would mean I’d achieved the object of the exercise – satisfaction within itself. If I inspired people to play or write, if I can get them to emote, I’ve done the job. Whether it’s sadness or happiness, that’s the idea of music.”

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.