All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

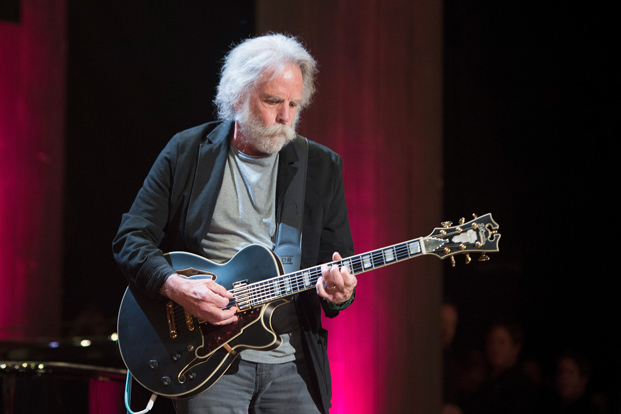

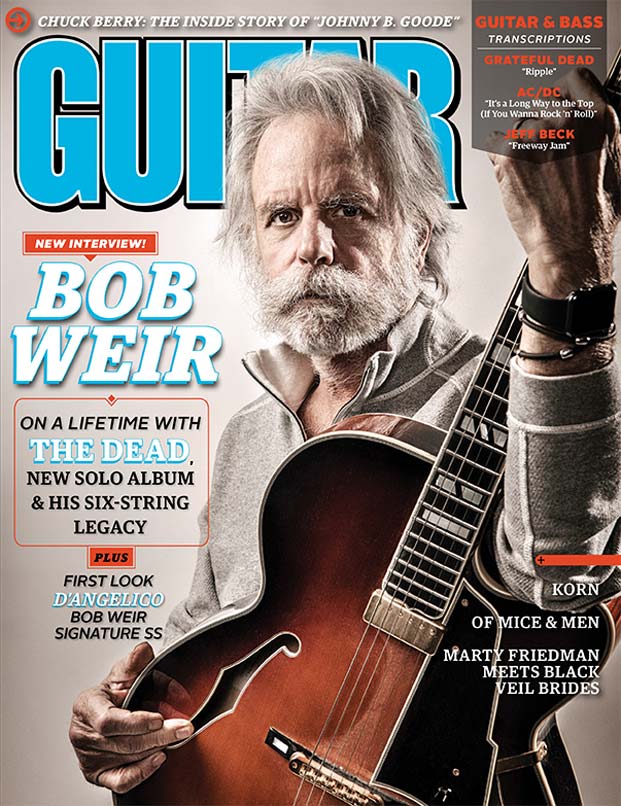

Bob Weir is on quite a roll. The release of Blue Mountain, his first solo album in 10 years—and his first collection of entirely new material in three decades—is the culmination of 18 very active months for the founding member of the Grateful Dead.

It started in the summer of 2015 when the Dead’s surviving Core Four—Weir, bassist Phil Lesh and drummers Bill Kreutzmann and Mickey Hart—played Fare Thee Well, five shows in California and Chicago which they said would be their final performances together.

Joined by Phish’s Trey Anastasio and keyboardists Bruce Hornsby and Jeff Chimenti, the group sold out Levi’s Stadium and Soldier Field, while thrilling legions of Deadheads around the world who watched live feeds in theaters and at home. It was the kind of triumph that was impossible to imagine when Jerry Garcia died in 1995. The Grateful Dead broke up a few months later but over the ensuing years began to regroup in various configurations.

The “final” Fare Thee Well shows were once again, predictably, not the end of the story. Soon after, Weir, Kreutzmann and Hart announced the formation of a new band, Dead & Company, joined by Chimenti and two unlikely new members: bassist Oteil Burbridge, fresh off 16 years in the Allman Brothers Band, and singer/guitarist John Mayer, best known for his pop songs and Stevie Ray Vaughan-inspired blues playing.

A new group in the shadow of the much-hyped final shows raised some critical hackles, but the fans never blinked. They understood that this was an entirely different venture. And indeed the group has reinterpreted the Dead’s vast, treasured catalog of music, with Mayer, Burbridge and Chimenti adding a more straightforward swing and youthful vitality. The band has been another big hit, selling out stadiums and amphitheaters filled with a mix of old Deadheads thrilled for another ride and a new generation of fans. Weir looks reborn with his new younger mates, singing and playing with vim and vigor.

“It’s a wonderful environment to just go for it,” says Burbridge. “It’s not about the execution. It’s about trying to find something new. The Bible says that love covers a multitude of sins and a really good jam where you go someplace you’ve never gone before will erase any mistake. That is the mindset of both the fans and the band. And Bobby is such an interesting player, who is so much fun to work with. Maybe because Jerry was playing long solos, Bobby found a really in-depth approach to rhythm playing, laying into chords all the way up and down the neck. He’s also a very underrated singer, with a pleading quality that really connects.”

Weir has always been a peculiarly underrated, sometimes even disrespected, guitar legend. Maybe it was his lack of soloing, the fact that the Dead’s soundman spent years mixing him too low or that he was always the clean cut handsome guy in a band of grizzled hippies. Probably it had more to do with three decades spent serving as a low-key sidekick to a revered guitar hero. But the mere fact that Garcia chose Weir as his foil and wanted him by his side for all those years speaks for itself.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

And Garcia was never shy about discussing his appreciation for Weir, noting in 1982 that his partner was “an extraordinarily original player in a world full of people who sound like each other.

“I don’t know anyone else who plays guitar the way he does, with the kind of approach he has,” Garcia continued.

Like Dead & Company, Blue Mountain pairs Weir with a younger generation of admirers, in this case a core of Brooklyn-based musicians orbiting around the band the National. Weir co-produced with Josh Kaufman, co-wrote much of the material with Josh Ritter and is backed by the National’s Aaron Dessner and Bryce Dessner on guitar and Scott Devendorf on bass.

Enjoy this excerpt from the December 2016 issue of Guitar World. For the full interview, plus our official Bob Weir Axology, check out the new issue of Guitar World.

Your collaborators on Blue Mountain feel like a left turn. How did you hook up with these guys?

our or five years ago we did a web broadcast from my studio [TRI] celebrating Jerry’s 70th birthday and we assembled a crew of young bucks to focus on Jerry’s songs, and the Devendorfs and their Brooklyn crew showed up in spades and we got along real well. I was impressed by how hard they listened and how economical they were in what they offered. A couple of years later they called, said that they had been talking amongst themselves and come up with the notion of doing a record of cowboy tunes with me. And that seemed like a great idea, like something right up my alley.

What about cowboy songs appeals to you?

Cowboy songs have always had an allure to me. I spent time as a kid, a young teen, in a bunkhouse kind of living that life. I’d spend my evenings with these old guys who had grown up in an era before radio had reached the nether regions of Wyoming and their notion of what to do for an evening was to tell stories and sing songs. I was the kid with a guitar so I became the accompanist and I learned a bunch of the tunes and the delivery and the esthetic—the ethos, if you will.

And is that where you learned country songs you brought to the Dead, like Marty Robbins’ “El Paso” and Merle Haggard’s “Mama Tried”?

Yes, more or less. I heard that stuff and developed an affinity for it and an understanding about how to approach it. Not necessarily those exact songs, but I could hear where they were coming from and understand their value.

You sing these songs like they are from the bottom of your heart. How difficult was it to develop that level of sync with a songwriter like Josh Ritter whom you had not known before?

He’s a gifted songwriter and there was actually a lot of back and forth. There weren’t all that many tunes that he offered that we did straight the same way. He’d come up with a line and I’d say, “Now how about this?” One thing tripped something else in my thinking and so forth. We went back and forth and I definitely had a feeling of collaboration on the songs—and that’s always been my preferred way of collaborating with guys like John Perry Barlow and Robert Hunter.

This album is so different from the Grateful Dead. That’s how you approached solo projects throughout the Dead’s prime—for instance, Heaven Help the Fool (1978) and Bobby and the Midnites. Ratdog became very Dead-like, so in a way this is more of a throwback.

Well, yeah! That’s really what I like to do because otherwise it’s not a vacation. If I’m going to use the same approaches and methods then I might as well do it with the guys I’m used to doing it with because we have that worked out. No one’s going to do it better with me. If I’m going to go exploring, then all bets are off and let’s just see what we turn up.

So is the goal finding a balance between Dead Bob and solo Bob?

[laughs] Yes! That’s what I’m always working toward.

“Ki-Yi Bossie” is one you wrote with your guitar tech, AJ Santella, and it’s a very interesting tune, addressing a 12-step program in the context of a real cowboy song. Did you set out looking to write a song about the program?

It’s rarely that direct! I don’t know how I found myself there. I had a notion for what the song was going to be about, that it would end with a guy who’s punching cows, which is his refuge from another existence. So I wanted to go to another existence first and I thought I better start out real bleak—and that took me to a basement room and a 12-step program. I took the 12-step to be literal and the cow punching to be a metaphor for chord punching—being saved by music. Well, yeah. That’s it.

The guy could have ended up in a monastery but then he wouldn’t have ended up on a cowboy record. I should make mention that Lukas Nelson kicked me along while I was developing the song and he had a lot to do with the setting—the rhythm, the key, the tonalities. This totally slipped my mind when I was doing the credits!

Will Dead & Company work up and play any of these songs?

I’m not sure that they work in that context. The bulk of them don’t lend themselves to what Dead & Company do. I’m hugely looking forward to playing these songs live with this band on tour this fall. They’re all good players and the places we’re playing are fun places that we’ve carefully chosen. We’re gonna have some fun on this tour.

I assume that’s what it’s all about for you at this stage of your career. Would you do anything that didn’t seem like it would be fun?

No. [laughs] I can happily say that I’ve come to the point in my life where the stuff that I do is the stuff that what I want to do.

Did you enjoy the summer Dead & Company tour as much as you seemed to onstage? The whole vibe was as positive and upbeat as anything I recall in Dead world for a long time.

Yeah. It’s been great all around and we’re starting to navigate uncharted waters, which was the whole idea of the endeavor from the beginning. We’re just now getting there, but the band was spitting fire all summer.

For the full interview, check out the December 2016 issue of Guitar World.

Alan Paul is the author of four books, including Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band and the Inside Story of the Album That Defined '70s as well as Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band – both of which were both New York Times bestsellers – and Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, a memoir about raising a family in Beijing and forming a Chinese blues band that toured the nation. He’s been associated with Guitar World for 30 years, serving as managing editor from 1991 to 1996. He plays in two bands: Big in China and Friends of the Brothers (with Guitar World’s Andy Aledort).