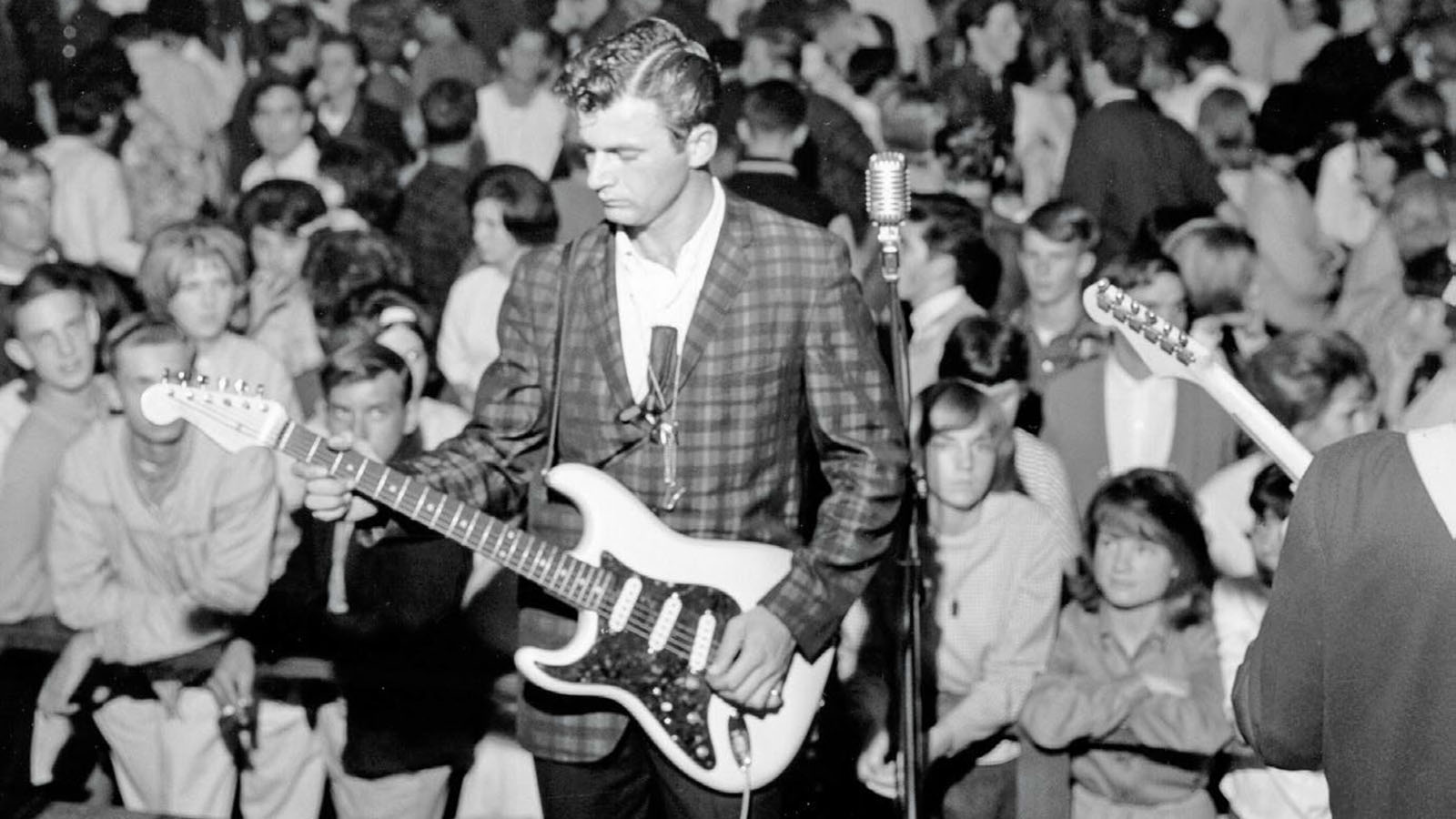

Dick Dale: the life and times of the King of the Surf Guitar

"I don’t know how to play a goddamned scale. I don’t know what a 13th is, or an augmented ninth. All I do is make the guitar scream with pain or pleasure”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I have a fond memory of walking with Dick Dale through the corridors of the Musical Instrument Museum in Phoenix some seven years ago. He said he could sense that the place was filled with spirits emanating from the ancient and modern instruments collected there, and even the building’s Indian sandstone facade. He felt the spirits were calling out to him.

Now Dick himself has entered the spirit realm. He left this life March 16, 2019, after a long battle with a number of serious illnesses including rectal cancer, diabetes, kidney failure and a heart condition. But his spirit is still very much with us. Dale’s devotees included guitar greats like Jimi Hendrix, Eddie Van Halen and Stevie Ray Vaughan.

While Dick Dale is known as the King of the Surf Guitar, his influence extends far beyond any single genre. A quintessential rock and roll outsider, he was one of the primordial axemen who established that rock guitar playing is all about pushing the envelope – louder, faster, harder. In the eternal quest for six-string satori, Dale is one of the masters you meet along the path.

“I’m not a guitar player,” he told me. “I’m just a manipulator of the instrument. I either get pain or pleasure out of it. I don’t know how to play a goddamned scale. I don’t know what a 13th is, or an augmented ninth. I could give a shit. All I do is make the guitar scream with pain or pleasure.”

Although he would come to be associated with the sunny culture of Southern California, Dale was born on the opposite coast, in South Boston, on May 4, 1937. Of mixed Lebanese, Polish and Belarusian descent, his birth name was Richard Anthony Monsour. He liked to point out that the suffix “-our” denotes royalty in Middle Eastern cultures.

Big band jazz was one of Dale’s earliest musical influences, absorbed from his father, Jim Monsour, who would later become his manager. The flashy, thunderous style of big band drummer Gene Krupa would inform Dale’s own intensely rhythmic approach to guitar playing. He messed with the ukulele as a boy, but ultimately settled on the electric guitar as his main instrument and his destiny.

A defining moment in Dale’s young life came when his family moved from Boston to Southern California in 1954. Just entering the 12th grade at the time, he became an avid surfer, immersing himself in a youthful lifestyle based around sunny beaches, crashing waves and hot rod cars. The mid-Fifties emergence of rock and roll fired his youthful fancy as well. Soon he was headlining his own band, the Del-Tones, at the Rendezvous Ballroom in Balboa, California.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

From the start, he stood out from the crowd of aspiring rock guitar slingers. A left-handed player, he simply flipped standard right-handed guitars upside down and played without reversing the strings. This would facilitate the lightning-fast, double-picked runs on the low E string that became one hallmark of Dale’s style. There’s a legend that he played so fast he’d melt his guitar picks.

It was a true outsider’s approach to the instrument — grabbing hold of it the “wrong way” and changing the course of music history. This is what rock and roll guitar is all about. Dale belongs to a small but select group of upside-down lefties that includes Albert King, Otis Rush, Elizabeth Cotten, Coco Montoya, Jimmy Cliff and Doyle Bramhall II. No one but Dale, though, put it across with quite the same panache.

One key ally in Dale’s quest for the ultimate guitar tone was Leo Fender, who was at the start of building his own legend as head of Fender Musical Instruments. He’d introduced his second game-changing electric guitar model, the Stratocaster, in 1954, and Dale became one of the first guitarists to adopt that iconic axe and take it to rock and roll fame. Dale often spoke of his first meeting with Leo at Fender HQ in Fullerton, California.

“I said, ‘Mr. Fender, I’m Dick Dale. I’m a surfer and I have no money. Can you help me?’ He looked at me and said, ‘Here, try this guitar.’ I grab it, and when I turned it around, held it upside-down backwards and started playing ukulele chords, Leo almost fell off his chair laughing.”

Dale’s main guitar, a ’62 Strat known as “the Beast,” was a left-handed instrument strung for right-handed playing that was given to him by Leo Fender. Sharing a love of gadgetry and country music, Dale and Fender became friends and collaborators.

They worked together to create the Showman, one of Fender’s all-time amp classics, and a significant early model to push the power up into the 100-watt range. Dale always said the amp’s name was coined by Leo after he’d witnessed his first Del-Tones performance at the Rendezvous Ballroom. “Dick,” he exclaimed, “you’re a real showman!”

Dale’s 1961 single, “Let’s Go Trippin’,” is often hailed as the first-ever surf instrumental. It was released on Deltone Records, a label that his father had launched to further his son’s career. But the track that really put Dale on the map was his sixth Deltone single, 1962’s “Misirlou.”

To this day it remains his signature song and one that exemplifies what we think of as the Dick Dale guitar style and sound. All the ingredients are in place – thunderous double-picked low-string runs and exotic melodic moves based on the Middle Eastern ‘Hijaz Kar,’ or double harmonic scale (E, F, G#, A, B, C, D#), which plays a flat second against the major third and seventh. Dale’s recording is based on a folk song known throughout the Middle East.

Capitol picked up Dale’s 1962 debut album, Surfer’s Choice, for distribution. It was the first of nine studio albums that Dale would make during his lifetime. His next album, King of the Surf Guitar, appeared in 1963. It helped transform Dale from a regional SoCal hit-maker to a nationwide star.

Dick and the Del-Tones appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show and youth-cult beach movies like 1963’s Beach Party and ’64’s Muscle Beach Party. Their influence spawned a glorious wave of garage band surf guitar hits like the Chantays’ “Pipeline” the Ventures’ “Walk Don’t Run” the Safaris’ “Wipe Out” and “Penetration” by the Pyramids.

Dick’s ride at the top was cut short by a trio of unfortunate circumstances. The British Invasion cut into surf music sales. Dale had a falling out with his father and manager of many years. And in 1966, he was diagnosed with rectal cancer. Recovering from a surgery he later described as “Neanderthal,” Dale retreated to Hawaii, half expecting to die there.

Instead he found a new way of life. He hooked up with Ed Parker, founder of the American Kenpo school of martial arts and a personal trainer to Elvis Presley. The Kenpo exercises and physical discipline helped nurse Dale back to health. And the school’s underlying philosophy gave Dale a fresh outlook on life and on his art.

In Hawaii and California he spent time studying with monks from the Shaolin Temple in China, an ancient seat of Chan Buddhism — the Chinese antecedent to Japanese Zen Buddhism — and the Shaolin school of kung fu.

So Dale bounced back, something he was good at doing. Most of his life was filled with ups and downs — severe health challenges and financial setbacks — but he never lost his spirit.

In the Seventies he built a real estate empire by investing money he earned playing Las Vegas with his first wife, Jeanie, a Polynesian dancer he’d met in Hawaii. But he lost it all when the couple divorced in 1986. By this point he’d already narrowly escaped having his leg amputated after a minor cut he’d sustained when surfing off Newport Beach became infected because the water was so polluted.

As a result, he became an environmental activist. By this point he was also an animal rights activist and a vegetarian. Clean living helped him overcome numerous cancer recurrences. Dale claimed that he never drank alcohol or did drugs in his entire life.

The Eighties saw a revival of interest in Dale. A Grammy-nominated cover of “Pipeline” that he recorded with Stevie Ray Vaughan led to a contract with American roots label HighTone records and latter-day discs like 1993’s Tribal Thunder.

Dale became an icon for a new generation of surf punks and skaters, before becoming an international phenomenon when “Misirlou” was featured as a key soundtrack song from director Quentin Tarantino’s blockbuster crime thriller, Pulp Fiction.

Never one for bright lights and big cities, Dale established a homestead in Twentynine Palms in the California desert. He and his second wife, Jill, had welcomed their son Jimmie into the world in ’93. The lad would follow his father’s footsteps as a guitarist and multi-instrumentalist.

Dale’s final years were marked by struggle with several serious cancer relapses. Through all this he was supported by his third wife and manager, Lana Parnell. The guitarist often remarked that he was compelled to keep touring in order to pay for the medicines and care necessary to keep him alive.

Hanging tough until his passing at age 81, Dale defied the odds and helped shape the course of rock history. I once asked him what he would most like to be remembered for. His answer was swift and sure:

“An attitude.”

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.