All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

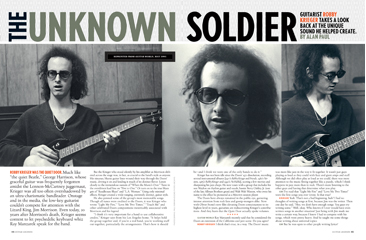

Guitarist Robby Krieger takes a look back at the unique sound he helped create.

Robby Krieger was the quiet Door. Much like “the quiet Beatle,” George Harrison, whose graceful guitar was frequently forgotten amidst the Lennon-McCartney juggernaut, Krieger was all too often overshadowed by an ultra-charismatic bandleader. Onstage and in the media, the low-key guitarist couldn’t compete for attention with the Lizard King, Jim Morrison. Even today, 20 years after Morrison’s death, Krieger seems content to let psychedelic keyboard whiz Ray Manzarek speak for the band.

But the Krieger who stood silently by his amplifier as Morrison slithered across the stage was, in fact, as crucial to the band’s style as anyone. His sinuous, bluesy guitar lines wound their way through the Doors’ music, driving it on and lending it much of its distinct flavor. Listen closely to the tremendous sustain of “When the Music’s Over.” Tune in the overdriven lead line on “Five to One.” Or turn on to the true blues grit of “Roadhouse Blues” and “L.A. Woman.” Using only minimal effects, Krieger created a wide-ranging, extremely distinct, guitar style.

He al so penned some of the group’s most memorable songs. Though all tunes were credited to the Doors, it was Krieger who wrote “Light My Fire ,” “Love Me Two Times,” “Touch Me” and other celebrated Doors compositions inextricably associated with Morrison and his legend.

“I think it’s very important for a band to use collaborative credits, ” Krieger says from his Los Angeles home. “It helps hold the group together and, if you’re a real band, you’re working stuff out together, particularly the arrangements. That’s how it should be —and I think we were one of the only bands to do it. ”

Krieger has not been idle since the Doors’ 1972 dissolution, recording several instrumental albums [1977’s Robby Krieger and Friends, 1982’s Versions, 1985’s Robby Krieger and 1990’s No Habla], scoring a few movies and sharpening his jazz chops. He now tours with a group that includes his son Waylon on rhythm guitar and vocals, bassist Berry Oakley, Jr. (son of the late Allman Brothers great) and Wah Wah Watson, who owes his name to the effecthe pioneered as a Motown session player.

The Doors have always remained in the public eye, garnering intense attention from rock fans and gossip-mongers alike. Now with Oliver Stone’s new film elevating Doors consciousness to its highest level in years, guitarists are rediscovering Krieger’s contributions. And they learn that the Quiet Door actually spoke volumes.

*****

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

GUITAR WORLD Ray Manzarek recently said thathe considered the Doors an extension of the California cool jazz scene. Do you agree?

ROBBY KRIEGER I think that’s true, in a way. The Doors’ music was more like jazz in the way it fit together. It wasn’t just guys playing as loud as they could with fuzz and giant amps and stuff. Although we did often play as loud as we could, there was more attention to the music fitting together like a puzzle, which I think happens in jazz more than in rock. There’s more listening to the other guys and having that determine what you play.

GW I’ve read that “Light My Fire” and “Love Me Two Times” were the first songs you ever wrote. Is that true?

KRIEGER Yeah. That’s not a bad beginning, huh? I had no thoughts of writing songs at first, because Jim was the writer. Then one day he said, “Hey, we don’t have enough songs. You guys try writing some.” Well, okay. Who knows if I ever would have even written songs in another situation? Just being with Jim made me write a certain way, because I knew I had to compete with his songs, which were pretty heavy. And he taught me some things about writing about universal topics.

GW But he was open to other people writing lyrics?

KRIEGER Yeah, he didn’t care. It was amazing. You’d think that a guy of his caliber would have only wanted to do his own stuff. Can you imagine going up to Bob Dylan and saying, “Hey, Bob, I wrote this tune for you”? That shows you something about Jim. He wanted it to be the Doors, not “Jim Morrison and the Doors.” He was adamant about that.

GW The End,” with its dropped-D tuning, tremendous length and strange lyrics, was some thing completely different, distinct from everything else.

KRIEGER Yeah, and it’s funny because that started out a s just a cute little love song : “This is the end, my friend, my beautiful friend.” And I got the idea to do an Indian tuning because I was into Ravi Shankar in a big way. From there, it started getting longer and more weird. And every time we’d play it, Jim would add more weird stuff to it.

GW Did the fact that your earliest training was on classical guitar have a big influence on your electric style?

KRIEGER Probably. I played flamenco for a couple of years before I touched an electric. The main influence of that is that I didn’t use a pick. But I think the main thing that influenced my style was just being in the Doors. The fact that we didn’t have a bass player or a rhythm guitar player made me pl ay a certain way in order to fill certain holes. And the fact that Ray had to play bass and organ at the same time made him play a certain way, which I think really made the Doors sound.

GW You’re one of the few modern players who plays with his fingers.

KRIEGER That’s true, but in the last 10 years or so I have started to use a pick. I read an article by [jazz great] Wes Montgomery, who didn’t use a pick either. He said that if he had had a chance, he would have learned how to use one. So, I figured, Well, maybe I should grab a pick.

GW In songs like “Waiting for the Sun” and “Soul Kitchen” you played riffs that have become particularly identified with you—signature riffs.

KRIEGER That wasn’t a conscious thing—it just happened that way. I didn’t sit down and say, “I need a signature lick here, this is what it will be.” Certain people play a certain way and other people—writers, critics —categorize it as such.

GWWhile your playing always h ad a lot of bluesy feel, you didn’t seem concerned with copping blues licks note-for-note like many of your contemporaries. Did guys like [Paul Butterfield Band guitarists] Mike Bloomfield and Elvin Bishop have an influence on you?

KRIEGER Oh yeah, I listened to the first Butterfield album [The Paul Butterfield Blues Band] for hours on end. But everybody either played like Chuck Berry or Mike Bloomfield so I just said, “Well, I’m going to play differently,” and went a different route. Koerner, Ray and Glover were some other guys I was really into—I thought those guys were really hip.

To be honest, “Love Me Two Times” came from one of their songs. The lick is very similar to one that Koerner does on “Downbound Train.” I told him that and he didn’t see it, didn’t think they sounded alike, but that was what inspired me. In fact, those guys inspired a lot of my licks.

And the idea to do “Back Door Man” came from John Hammond, Jr., another guy I really dug at the time. I heard his version and thought we could really do it great. But I still wasn’t trying to sound like anyone but me.

GW You started using a fuzzbox a lot on Waiting for the Sun—particularly on the title cut and “Hello, I Love You.” What were you using?

KRIEGER It might have just been a Gibson Maestro fuzztone, or it might have bee n these Acoustic amps we had with a built-in fuzz. Actually, I think it was a combination of those things. But there definitely was some heavy fuzz on that stuff—maybe too heavy.

GW But you didn’t really use much, effects-wise.

KRIEGER No, hardly any thing. I had the old Gibson and sometimes an Echoplex.

GWWaiting for the Sun also marked the first time you played slide extensively, for instance on “Hello, I Love You” and “Summer’s Almost Gone.”

KRIEGER I always loved playing slide and I think that’s the reason I got into the band in the first place: the guys liked the way I played slide. It’s funny that there’s not more slide on the first two albums, because I did play it a lot. But it seemed to keep getting passed over when song selections were made. I still play slide a lot.

GWSoft Parade was very heavily orchestrated, which was a real de parture for the band. Why did you go in that direction?

KRIEGER I don’t know, but it definitely was not my decision. I think it was because the Beatles did it, and everyone has to keep up with the Beatles. [laughs] That was an excuse, and it is sort of fun to get 30 guys in the studio and blast away. But it was a very difficult album to make. At first I hated it because it didn’t sound much like the Doors at all. But some of the stuff I really love, like “Wishful Sinful” and “Touch Me.” I think it worked really well on those songs.

GW MTV has been showing the “Touch Me” clip from the Smothers Brothers show, in which your eye looks a little worse for the wear. What happened?

KRIEGER Everyone asks me that. I usually say that Jim slugged me, but the truth is I was in an auto accident. I could have had makeup on it, but I thought, Maybe 20 years from now, people will ask me about it. [laughs] I really did think it looked kind of cool.

GW Having different names— “Morrison Hotel” and “The Hard Rock Cafe”— for the two sides of Morrison Hotel was an interesting idea. Was there a concept at work there?

KRIEGER Nah. That just came about after we finished the album and were thinking about the cover. Someone was downtown and noticed the Morrison Hotel. We saw the place and thought it would be a good album cover. Then we saw the Hard Rock Cafe, which was practically next door, and said, “Hey, let’s put that on the back.” Next thing we knew, there was a place in London cal led the Hard Rock Café. But both of those original places are gone now.

GW You started getting into the wah-wah on songs like “Peace Frog.” Were you influenced more by Motown or Sly and the Family Stone?

KRIEGER Well, I never really thought about that. To tell you the truth, that wasn’t a wah wah pedal on “Peace Frog.” It was a reverse pickup. We were just working on that last night—I haven’t done it in years. Wah Wah plays a wah wah on it now.

GW Was “Roadhouse Blue s” recorded live in the studio? KR IEGER Yes, it was. Not a lot of the stuff was, except on the first album and on L.A. Woman. As time went on, we had more money and started using more of the available tracks until the last album, where we wanted to get back. For the Doors, I think live was the best.

GW How did Lonnie Mack end up playing bass on “Roadhouse Blues”?

KRIEGER He just happened to be working in the Elektra studio that day, and I had always loved the way he played. So I asked him to play bass and he said, “Well, I’m not really a bass player, but I’ll try.” And after that, I always called him a bass player, which made him mad. He’d say, “I’m a guitar player, goddamit!”

GW Are you satisfied with Absolutely Live as the definitive live Doors document?

KRIEGER Fairly much so. I wish they had recorded more shows, because I know we did a lot better. But it’s not bad. There are some songs that could have been better.

GW Are there any secret live tapes around?

KRIEGER Not really. There’s some bootleg things but their qualities aren’t good and there aren’t any other well-recorded shows.

GW Do you think the Doors were a very different band live and in the studio? KRIEGER For the first couple of albums, the live shows and the records were pretty similar, mainly because we had played the stuff for a couple of years and were able to enter the studio and put it down quickly—especially the first album, which only took like five days. But as time went on, we slowed down a lot in the studio. Also, much stuff that’s on the records we rarely even played live. I think the only thing we ever played from Morrison Hotel was “Roadhouse Blues.”

GW The song “Hyacinth House” has some of the eeriest rock vocals ever recorded. It almost sounds like Jim died when he finished the song. Did you ever feel that way?

KRIEGER [laughs] It was a very odd vocal—a very, very odd vocal. I didn’t know what to make of it then, and I still don’t. We wrote that one night when Jim was over at my house and we were watching these raccoons in my backyard.

GW Does any of the Doors s tuff make you cringe now?

KRIEGER Sure, there’s always stuff like that. I won’t tell you which ones, but it’s nothing really bad. I’m not really embarrassed by anything. I’d like to change things here and there, but nothing major.

GW The use of “The End” in Apocalypse Now seemed to spark renewed interest in the Doors.

KRIEGER Oh yeah, that was very noticeable. They had the right to use any Doors song they wanted, and originally planned to use a whole bunch of them. They ended up only using the one.

GW Did it seem strange to have the song become so identified as a Vietnam anthem ?

KRIEGER Yeah, a little, because it was never meant to be that. But it worked so well that you can’t fault the guy. When I sat down to watch that movie in the front row of the big Cinerama dome in Hollywood , and the first thing I heard was my guitar, I just thought, Yeah! This is great! I dug it and I dug the remix too. It mad e me a little nervous that they were remixing it, but I think they did a g re at job.

GW Do you have any apprehensions about people’s perception of the Doors being determined by the ne w Oliver Stone film, The Doors?

KRIEGER Not really. I felt a little funny about the whole thing but it’s also very exciting.

GW Does the movie strike you as fairly accurate?

KRIEGER There are things that weren’t right, but overall, I would say it’s very right—amazingly so. I was worried that it would give a wrong impression of Jim or the Doors or what we were all about, but I think Oliver captured the essence of things very well—better than I thought possible.

GW How did it feel to see an actor portray you?

KRIEGER [laughs] It was a very strange thing, but I think he got me down really well. I hung out with the guy—Frank Whaley—and he’s an excellent actor. Just by hanging around together, he figured me out and did a great job.

GW Do you have any project s under way right now?

KRIEGER I’ve been working with Wah Wah Watson and Eric Burdon for the past couple of years. Both albums look like they might happen, but we’re still working on the songs. I think it’s going to be a real interesting combination.

GW What are you playing these days?

KRIEGER A Gibson ES- 35 5.

GW Do you use the same guitar for slide?

KRIEGER I have been lately, because I don’t feel like dragging my old Les Paul around. Ideally, I’d use my old Black Beauty.

GW What do you use for a slide?

KRIEGER Just a glass slide, but I can use anything if I have to. I used to use a broken champagne bottle— cheap California champagne.

GW When you hear these questions over and over, do you get tempted to just make stuff up?

KRIEGER [laughs] Sometimes, yeah. Only if I’m really bored.

Alan Paul is the author of four books, including Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band and the Inside Story of the Album That Defined '70s as well as Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band – both of which were both New York Times bestsellers – and Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, a memoir about raising a family in Beijing and forming a Chinese blues band that toured the nation. He’s been associated with Guitar World for 30 years, serving as managing editor from 1991 to 1996. He plays in two bands: Big in China and Friends of the Brothers (with Guitar World’s Andy Aledort).