All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

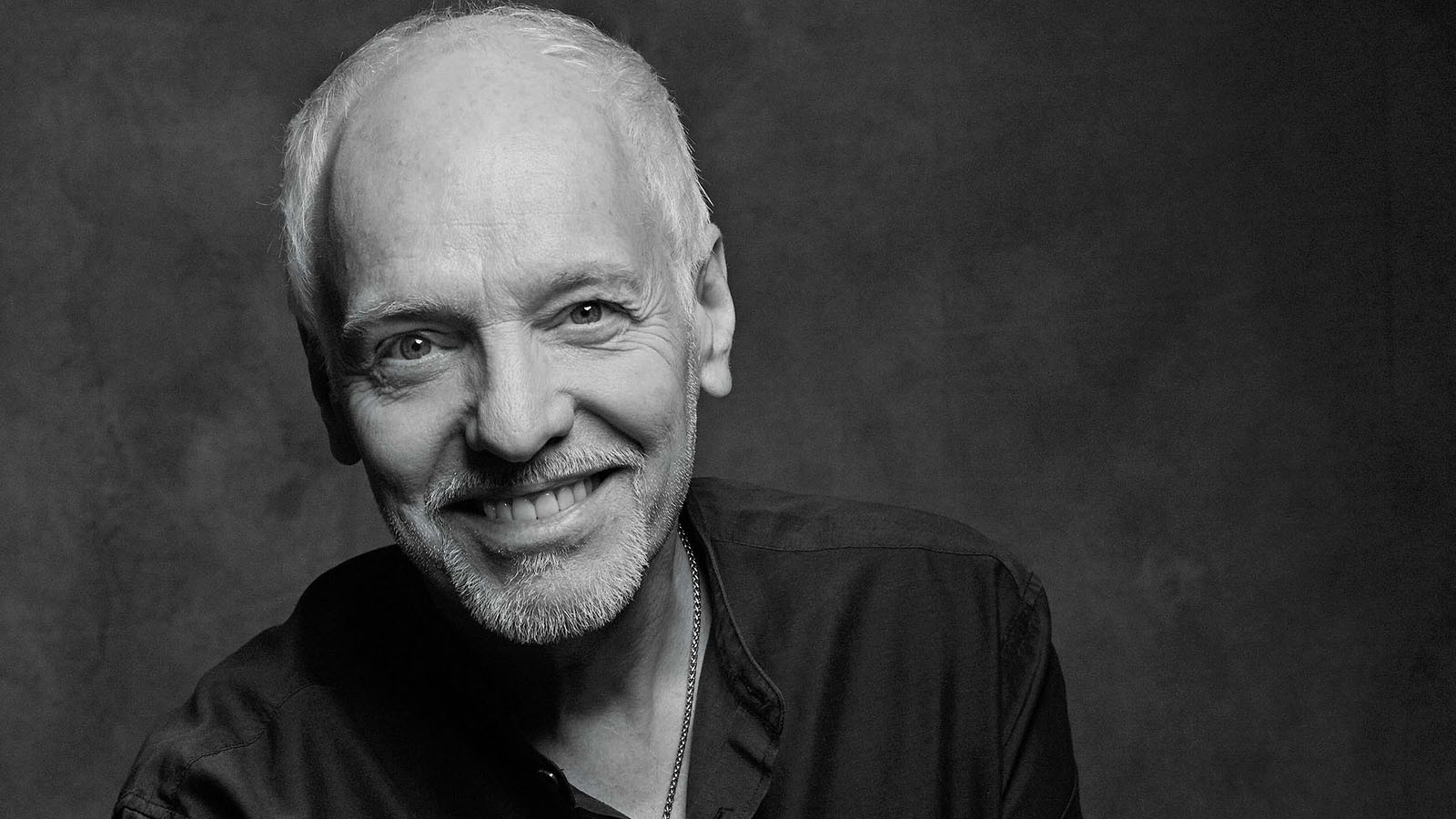

It was nine years ago when Peter Frampton first had the feeling that something wasn’t quite right. During a routine hike with his son in Big Sur in central California, his ankles felt tight. “I thought, ‘This is more difficult than it usually is,’” he says. “Every time we came to a hill, I was struggling.” But the guitarist, then in his late fifties, put it out of his mind. “I just chalked it up to getting older.”

As time went by, Frampton started to notice other gradual changes. He started having problems with his arms; it was as if his muscle responses were slowing down. Something as easy as putting a bag in an overhead compartment on a plane required more effort than usual. He considered seeing a doctor, but again thought, “It’s just age. It happens to all of us.” Four years ago, while performing at an outdoor amphitheater, he went to kick a beach ball that an audience member had tossed on stage — and fell backward. “It was embarrassing, but we all had a laugh about it,” he recalls. “It was like that TV commercial: ‘Help! I’ve fallen and I can’t get up!’”

Two weeks later, it happened again: he tripped over a guitar cord and fell backward. Now it wasn’t so funny, and by the third such onstage occurrence, Frampton knew something was seriously wrong. While at home in Nashville on a tour break, he finally saw his doctor, who brought in a neurologist. The diagnosis came back quickly: inclusion body myositis (IBM), an inflammatory muscle disease that affects not only the legs and arms, but also the hands and fingers. At present, there is traditional medicine for IBM, but Frampton has been working on various management treatments with Lisa Christopher-Stine, the director of the myositis clinic at John Hopkins in Baltimore, and he’ll soon begin a drug trial for his disease.

In the years following his diagnosis, the guitarist remained upbeat and went about his musical career as normally as he could. “I upped my workout routine,” he says. “I’m told that helps.” But last October, after he suffered a fall off a boat while vacationing in Maui, he realized his condition was worsening faster than expected. He spoke to his manager, Ken Levitan, and said, “We have to be careful with bookings from now on. I can still play guitar at the top of my game, but I can’t realistically say how long that will last.” Levitan proposed the concept of a farewell tour, and Frampton agreed.

“The idea was, ‘Let’s do this while I can still play great, because we wouldn’t want to wait a year and find out that things are different,’” he explains. “I’m like any other guitarist — I’m a perfectionist. I want to go out there and really do it, you know? I would never want to be on stage knowing that my playing was substandard but hoping that no one notices. That’s not me.”

One thing he wants to make clear: he’s not looking for, nor will he accept, sympathy. “This is life-changing, but it’s not life-ending,” he states emphatically. “I’m no different from anyone else. We’ve all got stuff we’re dealing with. This just happens to be what I’m dealing with, but I’m very positive about the future.” Fully aware that his ability to play at peak level might be compromised in the near future, he’s been holed up in the studio for the past few months with his band (Adam Lester, guitars; Rob Arthur, keyboards and guitar; and Dan Wojciechowski, drums) recording not one, not two, but three planned albums. “I’m stockpiling, for obvious reasons,” he says. “I want to play as much as I can while I still can.” And if he can manage it, there could be a fourth album on the way.

One of the projects is a two-part collection of blues classics—All Blues, and a sequel, All Blues, Too—the first of which will be released this summer. For guitar enthusiasts, these discs will prove to be a treasure trove of six-string riches, with Frampton stretching out luxuriously on what could be viewed as a Great American Songbook of the blues. Among the tracks he’s recorded are knockout versions of “I Just Want to Make Love to You,” “I’m a King Bee,” “She Caught the Katy,” “Georgia on My Mind,” “You Can’t Judge a Book by the Cover” and “Goin’ Down Slow.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Frampton’s buddy Larry Carlton appears on a stirring take on Miles Davis’ “All Blues,” and another pal, Sonny Landreth, turns up on a heartfelt rendition of B.B. King’s signature song, “The Thrill is Gone.” Frampton befriended King when the blues legend took part in his 2013 Guitar Circus tour, and he cherishes the brief time they spent together. “It was basically the last full tour B.B. did,” he remembers. “He would go on before me, which was always sort of strange because I’m such a fan. He was just the nicest man ever. He invited me on stage every night to play ‘The Thrill Is Gone’ with him. We’d sit on two chairs and we’d jam — it was marvelous. So this is my tribute to finally meeting this wonderful man and having been so fortunate to spend some time with him. I can’t wait for people to hear it.”

In your early years, you were into a lot of the rock and roll that most British kids were listening to. But you also discovered Django Reinhardt.

I did. I grew up listening to Django and Hot Club de France because of my parents — that was their dance band music of the Thirties and Forties. As soon as we got a turntable, my dad brought home two albums. One was The Shadows, my favorite band—they’re the reason I started playing—and the other was The Best of Hot Club de France by Django Reinhardt and Stephane Grappelli. I was like every other English kid who was into playing the guitar. I loved the Americans—Eddie Cochran and Scotty Moore. And there was Buddy Holly, of course. At first, I hated when my dad put Django on. “What is this acoustic stuff?” He wasn’t wearing glasses and playing a Strat, you know? But eventually I gave Django a chance, and he became a huge influence. He had such soul and dexterity, and his choice of notes was very interesting.

By age 18, you were already a pop star with the Herd. Was music fame in Sixties England as exciting as we think it was?

It was in many ways. I left school instead of going back to do my A Levels, and I joined the Herd when I was 17. Then the following year we did the residency at the Marquee Club; we got a record deal and management and the whole deal. Yeah, it was an exciting time, but you know, I was into the music. Pretty soon after, I started to work with Steve Marriott, and we made plans to form a band.

I was going to segue into Humble Pie. What was your relationship on a guitar level with Steve? How did you divvy up the guitar duties?

It was very democratic. Let’s choose “Stone Cold Fever,” for argument’s sake. I brought that riff into a rehearsal, and Steve picked up on it and answered me back. We were like, “Oh, this is good!” It was just jamming, basically, and he was always the first to point to me for the solo. We were big fans of each other’s guitar playing. He was more bluesy, and I was more lyrically tinged jazz-blues. We did a lot of harmony stuff together. We didn’t talk too much about it, it just sort of happened. Things started to change by the time of our third album, when we worked with [producer] Glyn Johns. The direction of the band shifted because Glyn didn’t think we were utilizing everyone’s best abilities. Before then, things were very democratic. Everybody brought in songs, and everybody was singing. So the emphasis shifted more toward Steve as singer; and let’s face it, he was one of the greatest voices in rock and roll.

What was your guitar setup then?

I used a series of Gibson SGs. There was the ’62, which was a red one, and I also used Steve’s white Custom SG with three pickups. In the beginning, we were all on baby amps. I used an Ampeg Echo Twin with a 4x12 cabinet. So that’s what I played on our early gigs. Eventually, we decided that we just weren’t loud enough, so we moved to Marshalls. So it was a 100-watt Plexi and a 4x12 slant cabinet. Straight in, no effects.

In 1970, an audience member, Mark Mariana, gave you that famous black 1954 Les Paul Custom that you started to use right away. What was so special about it?

Everything about the guitar just seemed perfect for me. The body, the neck — it was just a joy to play. But there was also a color to the sound that I loved. It was kind of a Frankenstein guitar in how it was wired. You couldn’t use the neck or bridge pickups without the center pickup being on, which I found ridiculous, but I learned how to use it. The two outside pickups were controlled by a master volume and tone control and a switch, but the middle pickup was sort of blended in with them. There was no switch for it. But it gave me a sound that I wasn’t expecting — a fat Strat sound. I was just a new color that I loved.

For a brief period of time, you did session work in Britain. Was that an area you really wanted to get your foot in?

Ah, there’s so much I’ve forgotten… I did John Entwistle’s Whistle Rymes. We’d become friends when the Herd toured with the Who. John called me up to play on a track, and that afternoon I think I replaced all the guitars. And then, of course, I got to work with George Harrison and the whole “Abbey Road mafia.” There was some work I did on All Things Must Pass, but before that I played on an album he produced for a singer named Doris Troy. She had sung on some Humble Pie stuff, and she was phenomenal. My friend Terry Doran introduced me to George at Trident Studios. I was nervous as hell, but George was so kind and gracious. He asked me if I would like to play on the session. So I said, “Well, OK… ” He handed me his red Les Paul and I start playing rhythm, and halfway through the song he stopped and said, “No, no, I want you to play lead.” That was a heady moment.

I ended up playing lead on her first single, and then George asked me back to play on the rest of the album. Because of that, I met Ringo and Jim Gordon, Nicky Hopkins, Klaus Voormann and Billy Preston. There was Gary Wright, but I knew him already. All of these people were there, and I’m just like, “I’ve got to pinch myself.” That was a very special time. And from there I played on Harry Nilsson’s Son of Schmilsson. Harry and I became lovely friends. He had his demons, like we all do, but he was the nicest man.

Between the time when you left Humble Pie and went solo, were other bands trying to hire you?

Well, Grand Funk asked me to join.

![Humble Pie in July 1970; [from left] Peter Frampton, Jerry Shirley, Gregg Ridley and Steve Marriott](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/hXPLmFqaGSuAVjg58ZPDWJ.jpg)

They did?

Oh, yeah. Humble Pie had toured with them in America and Europe. It was a phenomenal tour, and I got to know the guys really well. So when I announced that I was leaving Humble Pie, Grank Funk were the first people to say, “Will you join up with us?” I said, “Well, I’m thrilled and honored that you would ask, but I’ve got to stick with my guns and go this solo route.” It was a nice offer, but I’d already made up my mind.

Your use of the talk box became an integral part of your music. You scat sang with it, but you also doubled your guitar parts while using it. Where did that come from?

I don’t know! [Laughs] I was just messing around with it, and because I play guitar, well, I just did them together. I wasn’t really emulating anybody. It’s such a comical device, and it makes people smile, even today. I experimented with it, and I found that it sounds best down low, almost growly. I can talk with it, too; I communicate with people, and they can’t believe it. That’s why I use it — because people love it.

OK, the big album, Frampton Comes Alive! One of the things that’s so great about it is its big, sparky guitar sound. It just leaps out. Were the master tapes that good? Did you have to sweeten the guitar in overdubs?

No, it was right there. That wasn’t a case of having to save a bad recording. Eddie Kramer recorded it in a Fedco truck — that was one of the state-of-the-art mobile recording trucks — and he did a phenomenal job.

There’s so many thrilling, extended guitar solos on the record. “Lines on My Face” is gorgeous. Do you have a favorite guitar track on the album?

Well, that’s right at the top for me, and then “Do You Feel Like We Do?” That one sounds really great. There’s good solos, but some spots bother me. I wish we’d had Auto-Tune back then.

Oh, no. You’re kidding!

On a few things. But you know, whatever, it’s rock and roll. There’s some bad notes on that record, for sure, and I wish there weren’t. But it’s live and it’s all part of it. There have been some people who said, “Oh, it’s not live.” Really? Well, I don’t give a shit what you think. It is live! [Laughs]

Your first studio albums did well in the States, but they weren’t huge sellers. Was the label getting nervous? Was Frampton Comes Alive! a Hail Mary pass?

Not really. The Frampton record had come out in ’75, and we were out promoting that. We were playing “Show Me the Way” and “Baby, I Love Your Way.” That record sold much quicker than the others, and we were thrilled by that. A&M were pleased. The record wasn’t Gold yet, but it did 300,000 on its own, and that was steady progress. The tour was going very well. We were headlining; I wasn’t an opening act anymore, and we just thought, “OK, it’s time for the live album.” It was sort of a foregone conclusion, much like it was for Humble Pie. Did I expect that Frampton Comes Alive! would do what it did? Of course not.

For a time, your poster was on every teenager’s wall. Was that odd for you?

Well, the record was obviously phenomenally successful, which seemed overnight to some people, but of course it wasn’t. It’s strange; when Humble Pie put out the live album, I noticed that there were far more girls in front of the crowd than guys. And what’s funny is, when the band formed, we didn’t want to be screamed at anymore. Steve and I had both been in bands where that had happened, and now we were getting screamed at again. I was like, “What the hell’s going on here?” It was very flattering, but as we all know, a pop star’s career is 18 months, whereas a musician’s career is a lifetime. So with Fampton Comes Alive!, I crossed over from being a guitar player into the pop thing again. It was very frustrating, and I wasn’t thrilled about it. Now, couple that with the stress of going back in and following up the biggest album in history at that point. We had outsold Tapestry by Carole King. We had gone over 6.7 million in America and Canada. And… it was disappointing in one way. The whole thing really grated on me and was getting to me. There was a period when I wasn’t on stage, and I was trying to work out what had happened. It was a difficult period.

The next few years were pretty bumpy for you, but you rebounded in 1981 with Breaking All the Rules. There’s some really tough guitar playing on that record.

Oh, thank you! Yes, that definitely was one of the first turn-arounds, thanks to [producer] David Kershenbaum. He became a dear friend, and working with him was fantastic. I hadn’t really enjoyed working with a producer before, but that was a beautiful experience. That record was me sort of reclaiming my territory. I wasn’t going to be a pop star; I was going to be a strong songwriter, singer and guitar player.

What led you to join David Bowie’s touring band for his 1987 Glass Spider tour? Did you want to be just “the guitar player”?

Sure. Like I said, that’s all I wanted to be — a lead guitar player. That’s how I got into this mess in the first place. [Laughs] David and I would speak every now and then, and we’d hang out. He had heard my Premonition album — my first for Atlantic — and he called me up and said, “I love what you’re doing. Can you come play some guitar on my new record?” This was Never Let Me Down. I said yes immediately. I put my next album on hold, and I went to Switzerland and worked with David. We had a great time, and one night he just asked me about going on the road and playing guitar.

I was so thrilled to be playing with him. We’d played various shows together, but we never shared the same stage. I mean, we’d jammed as kids, but not since we’d made it. So this was a dream come true for me, because I’d always looked up to Dave. So there I was on the Glass Spider tour, on this giant stage, and he put me right there, in all these arenas and stadiums, and he reintroduced me as a guitar player. We toured the world twice. It’s funny, because I didn’t really consider what was happening at the moment, but a little later I realized how this was affecting me, what it meant to me. He gave me a wonderful gift, and I thank him for that. I’ve thanked him many, many times.

On that tour, you played parts originated by other guitarists. Did you have to “de-Peter Frampton-ize” your playing to some extent?

I think I referenced what was there, whether it was Adrian Belew, Robert Fripp, Stevie Ray Vaughan or all these incredible players. I referenced it, but I didn’t go whole-heartedly into re-creating. Some things had to be pretty exact. In “Heroes,” you need that one note that goes through the whole song. But on other things, Dave didn’t restrict me at all. It was phenomenal. He gave me this huge long solo at the end of “Loving the Alien,” and that was great. I enjoyed every moment of that tour. Like I said, it was a wonderful gift.

![Frampton and his band [from left], Dan Wojciechowski, Rob Arthur and Adam Lester](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/DsnejXPcuDXgZybfk2z4ZJ.jpg)

I wanted to bring up your album Fingerprints, which won you your first Grammy. Had you thought about doing an instrumental record before then?

I’d thought about it many times, but it just never seemed like the right time. I thought that, but when A&M asked me to come back to the label, Bruce Resnikoff asked me what kind of record I wanted to make. I told him “an instrumental record,” and he just went silent. But he relented, and pretty soon everybody got excited about it, especially when I was in the studio with the Shadows, Warren Haynes and Pearl Jam. It took a long time to record because I was moving around to different studios.

You did a wonderful version of Soundgarden’s “Black Hole Sun.” What drew you to that song?

Oh, well, it’s just a lovely song. When it came out, I just got goosebumps listening to it. I said, “That’s probably the best track I’ve ever heard.” I knew I couldn’t sing it better than Chris Cornell, but I could play it pretty well. So I went up to “grungesville,” up to Pearl Jam’s rehearsal room in Seattle, and I played with Mike McCready and Matt Cameron. Unfortunately, Jeff Ament had a family issue, so he couldn’t be there. But we had a great time. We had a wonderful guitar battle, and we kept everything that we did. We were literally playing together live, adding the solos at the end. A while later, I got a call from Chris Cornell to come and play it with him live. I did the instrumental version up until the end of the first chorus, and then he came in with the first verse. That was great.

Your ’54 Les Paul was thought to be gone forever after a plane crash, but you got it back a few years ago. Before its return, you were playing a Custom 1960 Les Paul Standard Reissue, a 1964 ES-335, and you worked with Gibson to create your signature line of Les Pauls. Were any of them true replacements for the Black Beauty?

Well, I’d given up trying to replace it. It was lost, and that was that. I worked with Mike McGuire at Gibson to make the Frampton PF Custom, and it was great. It was this close to what the ’54 sounded like. But you know… when I got that guitar back, I said, “No, they’re nothing alike.” The Black Beauty — I now call it the “Phenix” — is all mahogany, and it’s solid. So it’s got a darker, richer tone. You listen to “Lines on My Face,” and there’s something about it, that neck pickup. The other day I was working on the blues album. I was using the ES-335, and Chuck Ainlay, the engineer and co-producer, said, “I think we need a Les Paul on this one.” And I knew what he meant; he wanted the Phenix with that neck pickup. After I played the track with it, I just looked up and smiled. He said, “There’s something about you and that guitar.” I’m very, very, very lucky to have it back.

Have you planned your setlist for the farewell tour? Will it be something of a career retrospective?

Yeah, I would say so. We’re going to try to fit as much into two hours as we can. We’ll change it up at some shows, because I’m already seeing that there are people coming to multiple dates. I can’t thank them enough.

You’re playing Madison Square Garden, which you first headlined in 1977. That’s got to be exciting.

It is. It’s a strange reason to be doing it, obviously. I think it’s going to be a very emotional tour. My children are going to come to the Garden, and they’re going to come to the last date, which is at the Concord Pavilion in San Francisco. San Francisco is where we recorded Frampton Comes Alive! I can’t believe we pulled that off, but that’s wonderful.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.