“Being called a guitar hero was just awkward. Whether I’ve written a good song or not, that’s what counts to me”: Mark Knopfler on 40 years of Dire Straits’ Brothers In Arms – the guitars, the riffs… the pressure of learning to play in time

From his lucky ’83 Les Paul and Fleetwood Mac-inspired soloing to “getting away with murder” at the sessions, the Dire Straits legend opens up in his most revealing interview in years

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Behind an unmarked door in a nondescript West London street, you’ll find the recording studio of the world’s most reluctant rock god.

Do this job long enough and you’ll learn to spot the artists who project a carefully cultivated aura of false modesty, often blended with a phoney man-of-the-people vibe. With Mark Knopfler, you can tell, it’s absolutely genuine.

Over the course of our interview at the British Grove facility he founded two decades ago, the 75-year-old former leader of Dire Straits will tell us, with unblinking sincerity, that he considers himself a mediocre player who struggled among more capable studio musicians and squirmed every time he was anointed as a guitar hero.

We must respectfully disagree with our host, of course. Anyone who followed his band from the South London ratholes of the late ’70s to the stadiums of the mid-’80s would agree that Knopfler is a contender for the most beautiful, lyrical, shiver-and-tingle guitarist that Britain ever produced, the sound of his bare fingers dancing on the neck of his preferred ’61 Strat one of the era’s most magical sounds.

The evidence for his brilliance is writ large across a five-decade catalog, from the bob-and-weave outro of 1978's Sultans of Swing to the metallic resonator pluck of 1980's Romeo and Juliet and all over a 10-album-strong solo career that makes his peers look sluggish with its breadth and quality.

But if a Knopfler fan were to pick his or her desert island album, it would surely be 1985’s Brothers in Arms. Flowing from the Synclavier quack of So Far Away to the stormy title track’s molten solo – via the zydeco tootle of Walk of Life and the hairy-backed riff of Money for Nothing – this is Knopfler’s masterpiece. Riding the CD boom to sell 30 million copies, it made Dire Straits the biggest band on the planet, but it also drove the guitarist to overload and exhaustion.

These days, Knopfler doesn’t do much press – and he talks even less about Dire Straits. But with a new 40th Anniversary Edition of Brothers in Arms presenting these classic tracks alongside a dynamite full-length 1985 concert from San Antonio, he’ll make an exception.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

And if you offer him the right questions, this modest, self-effacing man speaks with all the eloquence of his fabled guitar parts.

It’s tempting just to say, ‘Oh, it’s nothing’ and downplay it, but thinking about Brothers in Arms now, it seems like that record meant so much to so many people

You must have been thinking about Brothers in Arms a lot recently because of this reissue. How does it feel to revisit a piece of music you recorded 40 years ago?

“Well, it’s tempting just to say, ‘Oh, it’s nothing’ and downplay it, but thinking about Brothers in Arms now, it seems like that record meant so much to so many people. I mean, that’s why we’re sitting here now. I think it was a combination of luck and events crashing into each other.

“We were so lucky to have intersected with Neil Dorfsman, who was such a great engineer. The record came out and we had a bunch of hits in America – that makes a hell of a difference. The CD had just been invented and they decided it would be a super idea to push Brothers in Arms in hi-fi shops. That’s where a lot of people first heard it. Then the singles made it in different countries and it became a worldwide thing. Next thing you know, you’re in the eye of the storm.”

You say in the sleevenotes that you only just had enough material for Brothers in Arms.

“Probably, yeah. Because we were touring so much. I would have been writing a lot on the road, in hotel rooms. And you got used to doing that. If you saw me walking up a hotel corridor holding a chair that had no arms, that was so I could play guitar on it.”

What do you remember about writing the key tracks?

“Walk of Life came from a big spell of listening to Cajun music – that’s the accordion lick, played on a keyboard by Guy Fletcher – combined with a rockabilly guitar rhythm. That would have been played on my red ’83 Schecter Telecaster.

“Money for Nothing was my ’83 Les Paul, and it comes from that clawhammer style. It’s just picking that pattern, and you mask off a lot of the notes, try to play the right ones. With that song, I was listening to a lot of ZZ Top, things like Gimme All Your Lovin’. That boogie they played was right up my alley. I still love it.

“That’s what it’s all about for me. Boogie is a big part of where I’m from. You know, it almost comes from a fingerstyle perspective, just cranked up a little bit and smokin’ along. Boogie doesn’t really have an overplayed vibe, it just rocks.

“It’s very interesting to me, the furniture of the title track on Brothers in Arms. If you think about the first four notes I play on guitar – I’ve tried doing other intros live, and they just don’t work. People have bought tickets and you can see them thinking, ‘That’s not Brothers in Arms.’ That’s not to say you have to play the guitar part the same way every time. Once I’ve played those four notes, then I can start to improvise.”

In the early days, you were known for single-coil sounds, but your 1983 Gibson Les Paul ’59 reissue played such a major role on Brothers in Arms. Did you always covet a Gibson?

Why did I choose to play the title track on the ’83 Les Paul? Maybe it was from listening to Need Your Love So Bad by Peter Green

“That’s putting it mildly! That moment of looking through the windows in Denmark Street – there was all of that. Every cliché. Why did I choose to play the title track on the ’83 Les Paul? Maybe it was from listening to Need Your Love So Bad by Peter Green [with Fleetwood Mac]. He was a beautiful guitar player. What a shame that he deteriorated. And that wasn’t a distorted guitar sound, but it was so powerful.

“My gear got more expensive as Dire Straits got bigger, but it still took a long time before I could get to a ’58 Les Paul. That was a bit later on, when I realized just how good they were. When Gibson made a bunch of repro ’58s, they took my ’58 and did a great job recreating it. They made about 55, and they’re fabulous. The tooling is so accurate – they even copied the scratches from my belt buckle.”

What other gear was central to Brothers in Arms?

“My ’61 Strat would have been in the mix. I know there was my roadie Ronnie Eve’s Marshall JTM45 that I’ve still got [Eve confirmed via email that the head was run into a Laney 4x12 belonging to AIR Studios in Monserrat]. My 1937 National resonator from the Brothers in Arms record sleeve – that would be on The Man’s Too Strong.

“Debbie Feingold, she was the photographer for that sleeve, and she’d marked that shot with lipstick saying, ‘I love this.’ And I remember saying, ‘I love it too.’ How could you not? It was such a great shot.

“That National looked like a spaceship, up against the sky like that. And that was Montserrat light, too. Spending so much time in AIR Studios, that taught me a lot about what kind of gear to get for British Grove.”

Did you enjoy being called a guitar hero in that period?

“No, that was just awkward. The world is bursting with fabulous players. Whether I’ve written a good song or not, that’s what counts to me. I gave up trying to be a great guitar player. I have enough to get by in the studio – that’s how I see myself as a guitar player. Not much more than that.

“But I can get away with it. If you’re the one who wrote the songs, you’re kind of allowed to be crap. Well, not to be crap, but you’re given some leeway because you wrote the thing. The other guys are there, really standing by their instruments: ‘I play piano,’ ‘I play bass.’ Like, ‘I’m good at this and that’s why I’m here’ – and boy, they are. I got away with murder.

“But the guys that really know their business – the session guys, making a living with their instruments – that’s a whole other kettle of fish. I remember, in the solo band one day, I said, ‘Oh, I’m sorry about the [mistake] in so and so’. And Richard [Bennett, guitar] said, ‘Well, the singer is always right!’”

How many takes did you need to nail the Brothers in Arms guitar parts?

“I was getting a little bit better. I was still learning how to play in time, after years of working in studios with engineers who would say, ‘You’re rushing there.’ And you’d say, ‘No I’m not.’ And they’d say, ‘Yes, you are.’ Because you didn’t recognize it. You didn’t know it yet. You think you’re playing in time – but you’re not.

“You have to learn that. It takes a long time, especially if you’re playing 8th and 16th notes with your thumb and fingers. That’s just part of the journey. Some of the very finest musicians have told me they had to learn the same thing. Glenn Worf [bassist] was just the same. There was a guy in his band who told him, ‘You’re not playing in time.’ And he said, ‘The hell I am!’”

The solos on Brothers in Arms are very different from, say, Sultans of Swing. You seem to really let each note breathe. Do you think your philosophy to lead work was changing?

“It probably was. You start to realize how much real estate there is in a bar – where you can put the notes or, if you have a band of that quality, where you can lean on the timing a little bit. But there wasn’t really time to think about it. You’re just moving on.

“The band had developed. It was a lot louder and more powerful, with keyboards becoming more important. That then makes you think in a different way – more inversions, perhaps. But I didn’t force it. I didn’t stop picking on country tunes. I was still doing rootsy things.”

In the wake of Brothers in Arms, some of the guitar world’s most respected figures wanted to play with you.

“I remember, Chet Atkins gave me a [call]. Because we were both pickers in that sense – but, of course, Chet was otherworldly. I used to go round to his office and hang out, and I’ll never forget, we once played and sang the song Kentucky all morning.

Chet had such facility and knowledge, and yet what he wanted to do was play Kentucky – which has two chords – all morning long

“Chet had such facility and knowledge, and yet what he wanted to do was play Kentucky – which has two chords – all morning long. He’d say to me, ‘You’re pretty good, but you’re no Mark Knopfler.’ He always had good jokes. You know, you’d get to the end of something and he’d go, ‘Very educational.’ And then he’d say, ‘A little below above average.’ Or something like that. Very dry.

“I only remember him being slightly put‑out once, when John Fahey said he’d been double-tracking. Chet was not pleased by that. And he wrote to whatever magazine it was and said, ‘You can learn to do this with your own two hands; you don’t need double‑tracking.’

“I mean, Chet liked multi-tracking too, of course, but only if he was doing something even more complicated. But he could play Yankee Doodle and Battle Hymn of the Republic at the same time.”

What do you remember about the hysteria that set in after Brothers in Arms?

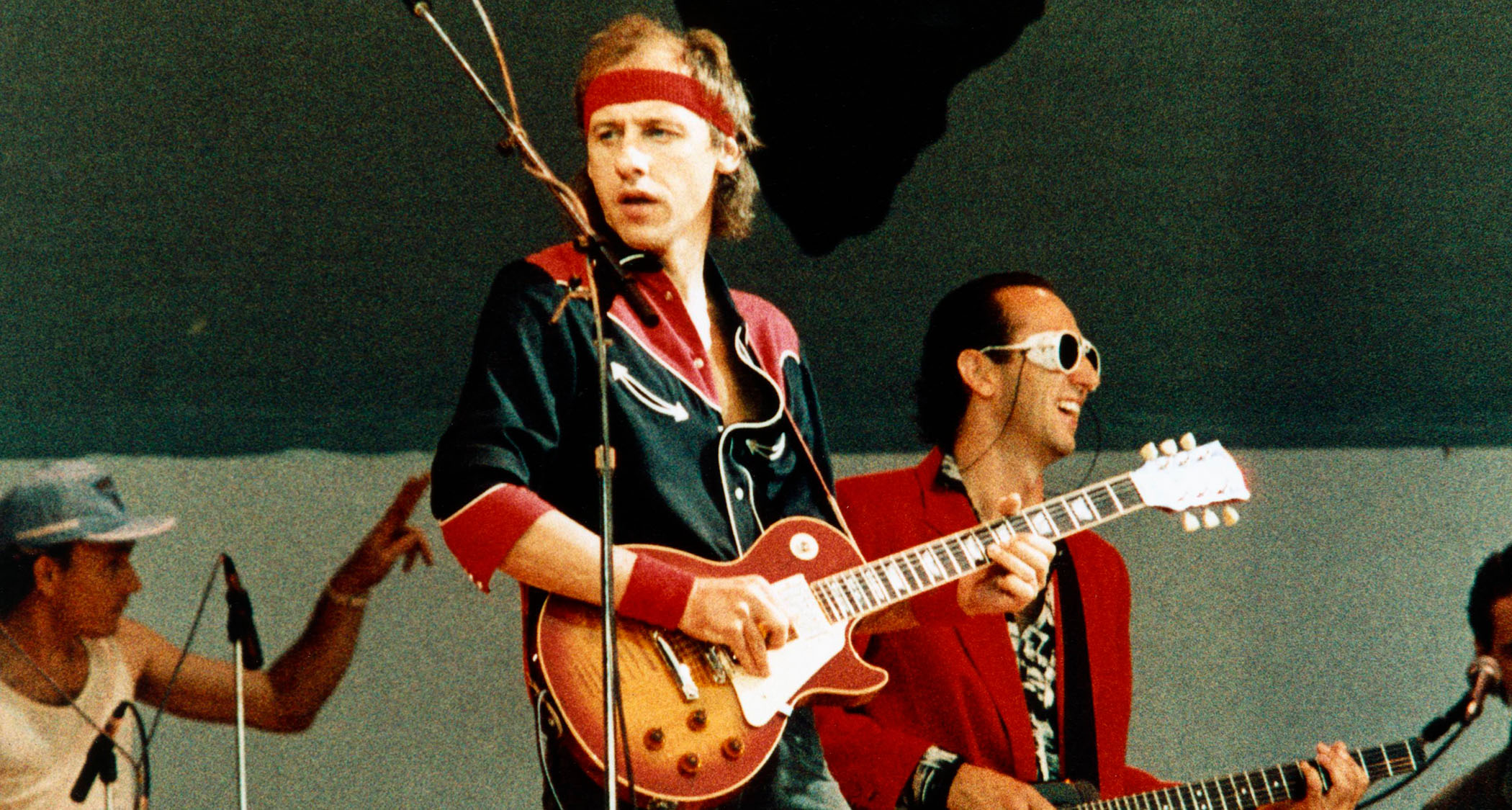

“I remember doing the Mandela show [Nelson Mandela 70th Birthday Tribute, June 1988]. We were walking up to the stage – Eric Clapton was playing with us that night – and somebody said, ‘Oh, there’s 650 million people watching.’ And I thought, ‘Oh, what have I done?’

“I heard our sound man’s voice from the desk and he’s going, ‘I can’t hear a fucking thing!’ I thought, ‘Oh shit, there’s been a breakdown, he’s lost his sound.’ But what he was talking about was the noise in the stadium before we went on.”

Much of the Brothers in Arms gear was sold in the charity guitar auction you held in 2024. Did it hurt to see it go?

“Yeah, of course, when you’re saying goodbye to that ’83 Les Paul and that Schecter Tele. But it’s fine. You’re not going to sit and play all those guitars. It’s time to thin it out a bit. Give them another home. Let them be played by other people.”

What are some of the real treasures still left in your collection?

In a lot of ways, I’d rather have a 330 than a 335 because the P-90s are such wonderful pickups

“Tony Joe White gave me his blonde Gibson 330 that he used for Rainy Night in Georgia. We’d become pals and Tony had switched to a Strat, and I was ’round at his house playing one day. I’d given him an acoustic guitar as a present. And he reached under the sofa and he pulled out this dusty old case. And he says, ‘Mark, I want you to have this guitar. I don’t play it anymore.’

“I opened up the case and the fingerboard is so sweat-pitted it’s got shell shapes between all the frets. And I said, ‘I can’t take this, Tony.’ And he said, ‘Hell, take it; I don’t want the damn thing.’ So I put a new fingerboard on it and I’m never without that on a recording session.

“If I was recording now, that 330 would be here. I love that guitar. And actually, in a lot of ways, I’d rather have a 330 than a 335 because the P-90s are such wonderful pickups.”

If you were tracking Brothers in Arms today, would you play the parts differently?

“I probably wouldn’t be able to play them so well now. But I’m hoping to put my head down and really get back into some proper playing in the near future. Covid slowed me down a lot. I’ve had it three times. And then, if you’re away from the guitar for a while, your pads get softer and you lose your facility a little bit. So I’m really looking forward to improving.

“I think what happens is, you develop lazy techniques. I’m forever doing that. You know, half-chords, these little semi-shapes. It wouldn’t make a teacher very happy. I mean, nothing I do would make a guitar teacher happy.”

Do you think guitarists can keep improving all the way through their lives?

“I don’t know about ‘improve.’ I think you just find new things to inspire you. Because there’s just no end to it. It’s really all there for you, if you just want to sit down and be bothered to learn it.”

If you were to look in a guitar shop window today, would you be as excited as when you were a young man?

“Absolutely. I’ll still walk across the road to look at motorbikes. And it’s the same with guitars. What’s wrong with me? I’m stuck in my childhood. But I think you need to have that semi-obsessional point of view. It doesn’t matter what it is.

“I mean, how could you succeed in football if you didn’t love the game, even if you were earning a quarter-of-a-million pounds a week? If you didn’t love the game, it would show. It has to border on obsession. And I think people like to be around that. Just to see these maniacs.”

Finally, do you think Brothers in Arms is Dire Straits’ best record?

“I never think in terms of ‘best.’ You absolutely can’t. You might as well be asking, ‘What’s your favorite cheese?’”

- Brothers in Arms (40th Anniversary Edition) is out now.

- This article first appeared in Guitarist. Subscribe and save.

Henry Yates is a freelance journalist who has written about music for titles including The Guardian, Telegraph, NME, Classic Rock, Guitarist, Total Guitar and Metal Hammer. He is the author of Walter Trout's official biography, Rescued From Reality, a talking head on Times Radio and an interviewer who has spoken to Brian May, Jimmy Page, Ozzy Osbourne, Ronnie Wood, Dave Grohl and many more. As a guitarist with three decades' experience, he mostly plays a Fender Telecaster and Gibson Les Paul.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.