All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

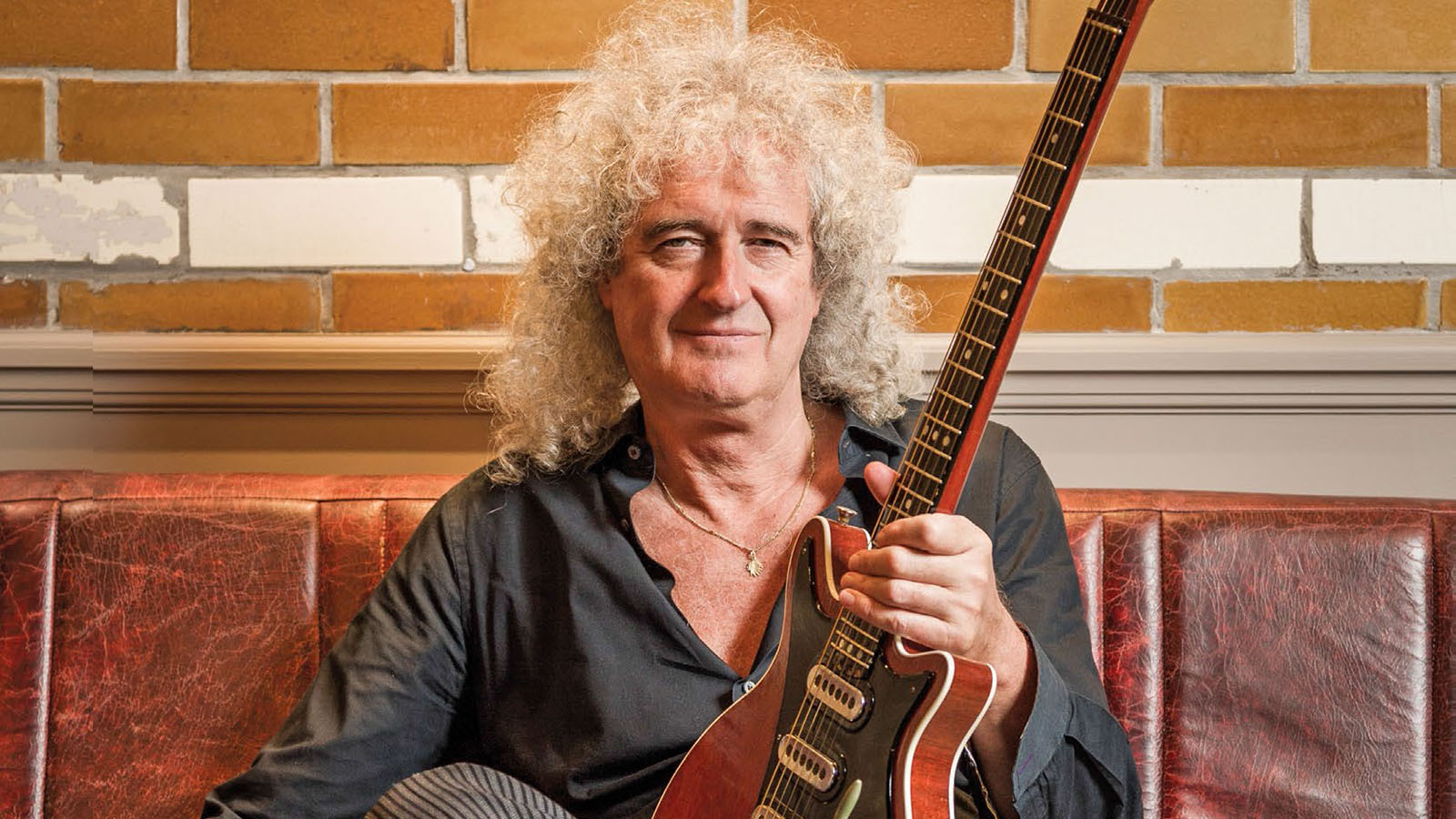

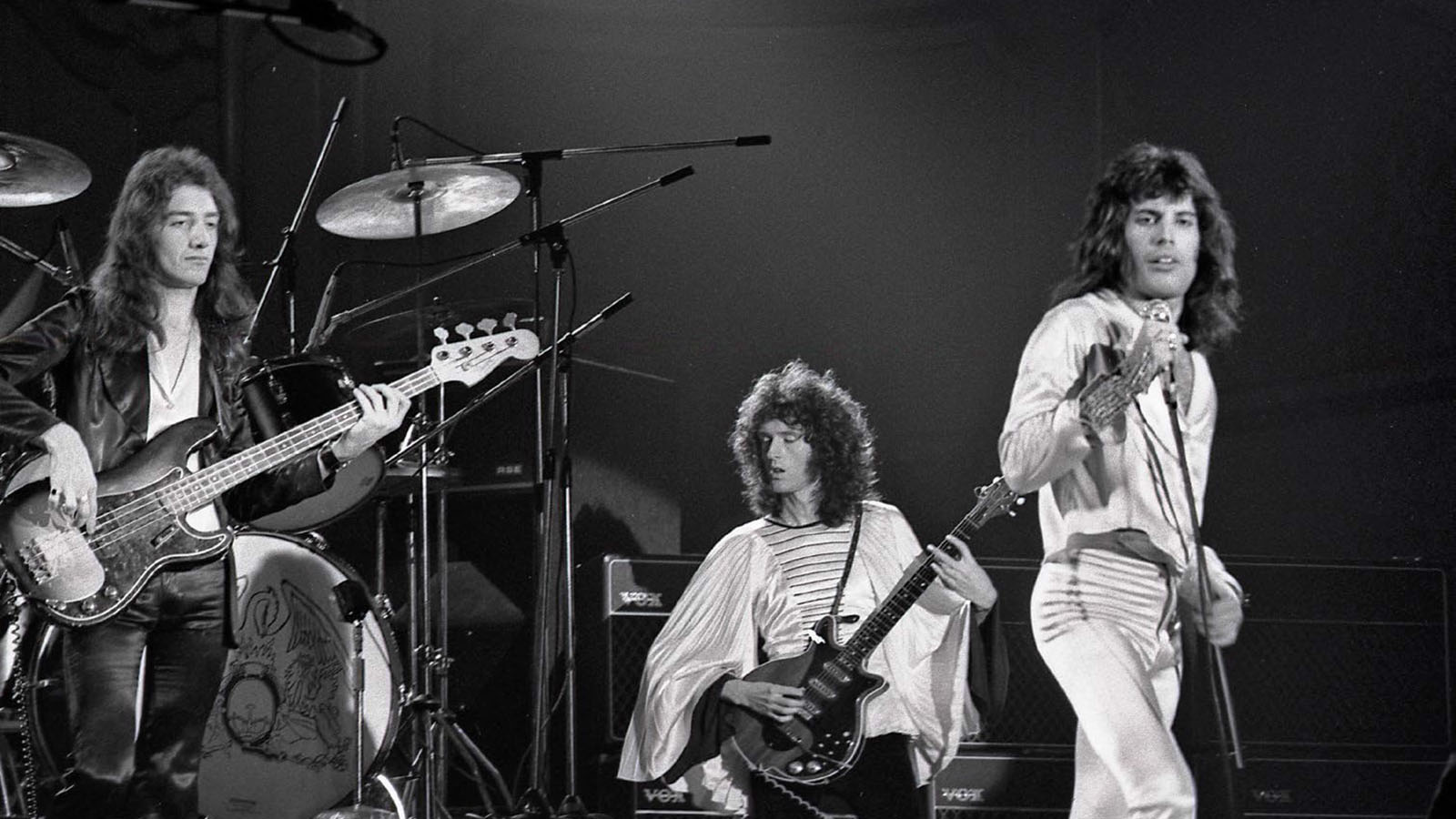

Best of 2019: Even by most multi-taskers’ standards, Brian May puts everybody to shame. He’s not only one of most distinctive guitarists on the planet, but he also co-founded and composed songs for one of the world’s top-selling bands, Queen. As if all that weren’t enough, May somehow found a little time in his schedule to become an astrophysicist, of all things, having received his Ph.D. from London’s Imperial College in 2007.

All of which begs the question: Is there anything this guy’s crap at?

May lets out a chuckle and says, “Oh, sure. I suppose there’s some things.” After racking his brain for a second, he admits household chores aren’t his strong suit. “I’m rubbish at that stuff. Ask my wife. I’m always leaving cups of tea sitting in all of these hidden places, and they turn up months later all full of mildew. That’s my worst trait.”

Housework aside, May’s achievements continue to pile up. It’s indeed rare for any band to sustain its popularity decades after its last recorded work, but Queen are riding a wave of popularity that’s practically unheard of. Thanks in large part to the behemoth 2018 film Bohemian Rhapsody, now the most successful music biopic of all time (with worldwide box office receipts in excess of $1 billion — not to mention four Academy Awards), the band’s catalog has stormed back onto the charts. Shortly after the picture’s release last fall, Queen achieved a career first with not one, but two albums (the movie soundtrack and the band’s 1981 Greatest Hits collection) on the Billboard Top 10.

“I mean, who could have predicted it?” May asks rhetorically, almost sounding bewildered at the magnitude of the film’s reach. “We thought it would do well with the fans, but we didn’t imagine how fully it’s been embraced. People are going to see it five, six times. They’re singing along and crying. I met people in Asia who saw it 30 times. It’s extraordinary. We couldn’t be happier.”

Responding to critics who took issue with the movie’s reshuffling of chronological events, May says, “We weren’t making a documentary. It wasn’t supposed to be ‘This happened, and then this happened.’ This was an attempt to get inside Freddie Mercury and portray his inner-life — his drive, his passion, his fears and weaknesses. Also, we wanted to portray his relationship with us as a family, which was pretty much a part of what made him tick.” He pauses, then adds thoughtfully of the band’s late frontman, “And I think Freddie would love it, because it’s a good, honest representation of him as a person."

Bohemian Rhapsody had a long and sometimes troubled history before reaching the screen (before Rami Malek was cast in the role of Mercury, Sacha Baron Cohen was briefly attached), and for May, who along with drummer Roger Taylor served as a creative and musical consultant on the film, the process often proved difficult. “There were lots of battles we had to face,” he says. Even after the film wrapped, the guitarist had to fight execs at 20th Century Fox to be able to record his own version of the studio’s theme music that begins the picture. “They didn’t want me to do it because they thought it would open the door for lots of other things. But in the end, they let me do it, and they came through for us in every respect.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

One of May’s other roles on the film involved coaching actor Gwilym Lee, who portrays the guitarist, in the finer points of his unique style on the six-string, which even called for the actor to play with a British sixpence instead of a standard pick. Fortunately, Lee wasn’t a neophyte on the guitar, so he was already versed in the basics.

“Gwilym’s a good player, but he wanted to get into how I do stuff and observe me close-up,” May says. “We sat together with two guitars and played the songs he was going to do in the movie. He absorbed it all very rapidly. What I didn’t realize was that he was also observing all of my mannerisms and the tone of my voice. When my kids saw the first trailer of the film, they said, ‘Dad, did you overdub your voice?’ I said, ‘No, he’s an actor, and he’s absolutely nailed me!’ ”

Beyond Bohemian Rhapsody’s gargantuan box-office take, May attributes Queen’s sustained hold on the public’s consciousness to the durability of their songs. “The songs are the main pillar, but that’s a very complex area in itself,” he says. “Those songs were generated during periods of stress. We were very fortunate to have a strong combination of personalities, but I think we were always on the verge of breaking up. Oddly enough, that’s where we got our strength, because we were pulling in different directions. We had four varied talents between us.”

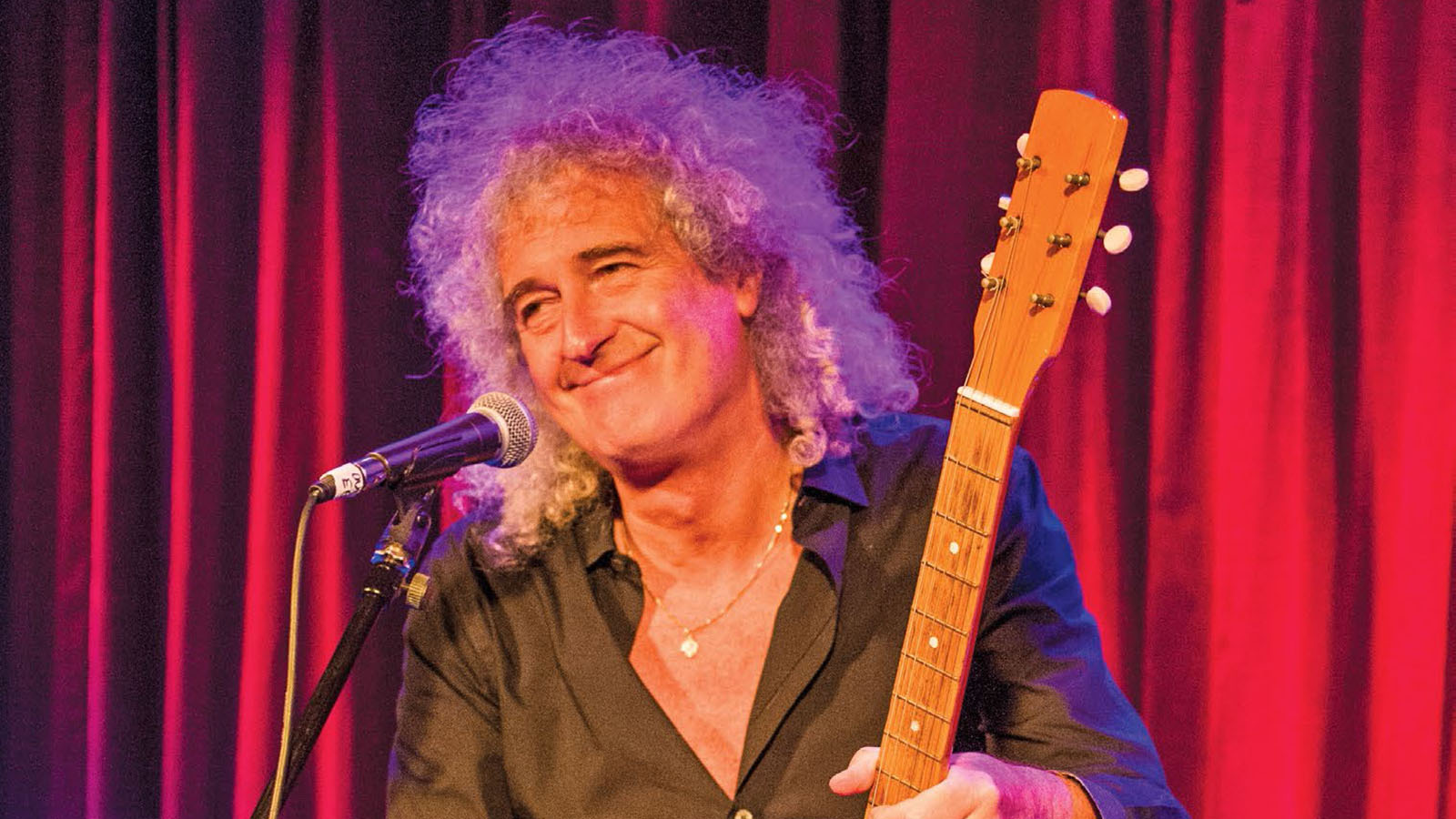

Queen stayed off the road for more than a decade following Mercury’s AIDS-related death in 1991, but in 2004, May and Taylor resumed touring with singer Paul Rodgers fronting a revamped version of the band (bassist John Deacon had retired). That configuration, Queen + Paul Rodgers, enjoyed a run of highly successful worldwide treks before splitting in 2009. Two years later, May and Taylor invited American Idol runner-up winner Adam Lambert to join the group, and — as Queen + Adam Lambert — they’ve gone down a smash.

This summer, the band will embark on a North American arena tour, and with Queen still basking in their Bohemian Rhapsody glow, the run just might feel like a victory lap. “I think performance is still a big part of our history,” May says. “We still go out there with Adam and do it at the top level. I don’t think anybody could have predicted that, either. What’s great is, Adam doesn’t feel like a replacement at all; in his own way, he’s an innovator on stage. He’s part of our new balance.”

Let’s go back to the beginning. In 1963, you were obviously a serious student in school, but at the same time you wanted to play guitar. Did those two pursuits conflict with each other?

They did conflict, and the policy of the school was that guitar playing was immoral and illegal — it was the work of the devil. We had to sneak guitars in and play in cycle sheds during lunchtime. We had to be rebels. All of those sorts of ways of formally learning to be a rock star didn’t exist in 1963. It was regarded by many as a big waste of time.

Your father helped you build your guitar, the Red Special. Was he was OK with the guitar taking time from your studies?

My dad’s a bit of an enigma. Yes, he did support me, and we made the guitar together, which was a wonderful bonding experience for the two of us. But when it came to me giving up my studies to go out and play guitar, he was violently against it. He was heartbroken I was considering giving up everything he thought that was going to secure my future — and everything that he felt he had made sacrifices to enable me to do. It was a very emotional thing, and we hardly spoke for about a year and a half.

If the guitar you built didn’t pan out, what would you have wound up playing?

Oh, well, we would have made it work; we wouldn’t have given up. [Laughs] We were absolutely determined, and we did a lot of experimental stuff as we went along. Having said that, it could have been much less of a success than it turned out to be, and then history would have been different. But I don’t know how because I couldn’t afford to buy a guitar for all those years. It would have been much later before I was able to buy a Fender or a Gibson or anything of that class.

You’ve played the Red Special throughout your career. Given all the technological changes that are available now, if you could go back in time, is there anything you wish you could change about it?

I wouldn’t change anything. No, it all worked out very well. [Laughs] It’s really part of my body, and everything about it is right for me. Now, how that happened is a bit of a mystery. I think some of it was intuition and good planning, but some of it was luck. One of the big unknowns was having those acoustic pockets in it. I had this idea that the guitar should feedback a certain way — not the scream-y kind of feedback that happens through pickups. I didn’t have any theory behind that; I was just lucky it worked out right.

Your style of playing is almost impossible to dissect. It’s hard to detect your influences. Who did you listen to as a kid?

There wasn’t much to listen to at that time, so kids like me would listen to everything they could lay their hands on. You wouldn’t call Django Reinhardt, Charlie Byrd or Chet Atkins rock guitar players, but they were all big influences on me. We were all Shadows fans, so Hank Marvin was a massive influence.

I just seized upon anything I could find. I didn’t know who James Burton was in those days, but he was a big influence. The way he bent strings, it sounded like a vocal. That’s what fired me up. And there was Buddy Holly, not so much for string bending, but his incisive rhythm playing was a big influence on me. And those harmonies! I started to appreciate what could be done with the vocal harmonies. Those things chill me to the bone still — “Oh, Boy!” and “Maybe Baby.” I still put them on and marvel at where they came from.

Queen also seemed to occupy their own lane. You weren’t doing the blues thing like Free, and you weren’t aggressively prog like Yes and Emerson, Lake & Palmer. Were you guys trying to stay away from what everybody else was doing?

I think the real influence is from all of those things. A couple of songs in our early days were very much modeled on the way Free wrote. By that time I’d been exposed to Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix, and that was life-changing. To us, Hendrix was the great god. I still can’t understand where that stuff came from. It’s like he came from another planet.

I mentioned harmonies — I came from Buddy Holly and the Crickets, the Everly Brothers, the Beatles. The Beatles built our bible as far as musical composition, arrangement and production went. The White Album is a complete catalog of how you should use a studio to build songs. “Happiness Is a Warm Gun” and “Dear Prudence” are blinding examples of how music can be like painting a picture on a canvas. In a sense, the Beatles were unburdened because they didn’t have to play the songs live. We became passionate about building stuff in the studio but also making it come to life on a stage.

In the early days, when you didn’t have full control over your show, was it hard to get your guitar sound to your liking on stage?

As soon as I found a Vox AC30 and a treble booster, which was given to me in concept by Rory Gallagher, I had my sound and I never had a problem. It was always the way I wanted it to be. It was my voice, and I was happy. I’m always looking to improve it, but that’s the basis and it hasn’t changed. Those Class A valves give you the smooth spectrum from clean to incredibly limited and saturated. Combined with my guitar, I got all the variations in tone I was looking for.

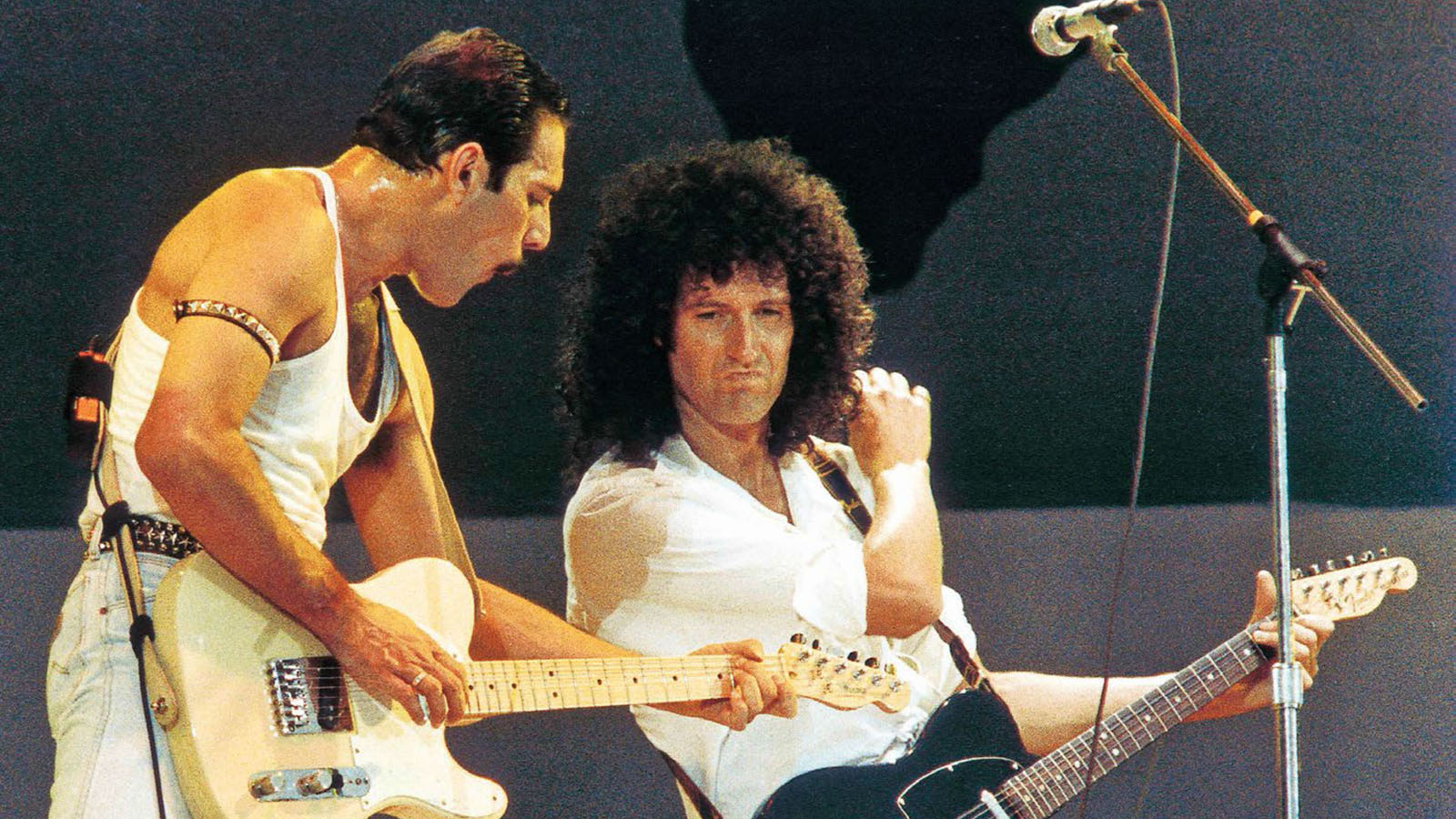

People often think of Freddie as a pianist, but he occasionally played guitar, and he would write with one, too. What kind of guitarist was he?

He was very good on the guitar, very unorthodox — all downstrokes. He wrote the riff for “Ogre Battle” [from 1974’s Queen II]. I used to play it with up- and downstrokes, but he was all downstrokes. Imagine how fast his right hand was moving! He had a frenetic energy on the guitar, which came across very well in that song. He played the rhythm on “Crazy Little Thing Called Love.” I wanted to sound as good as Freddie did on that record, which was damn good. He kind of left the guitar after a while and concentrated more on the piano. In the latter days, he even left the piano behind. He just wanted to be a performer who ran around and had the freedom to be a frontman.

Speaking of performing, you and Freddie pioneered some of the rock star poses people use today.

Did we? [laughs]

I think so. Sure.

I don’t know where it all came from. We had our influences, but we were never choreographed. We did it all instinctively, but there was an awareness of energy flow on stage. I think Japan changed us. We went to Japan and were treated like we were the Beatles. Every move we made was greeted by some kind of response from the audience, so we learned very quickly, instinctively, to use that. I think I wasn’t a very physical guitar player in the beginning, but experiencing the Budokan and that wall of appreciation molded us into people who are much more physical and responsive to what the audience felt.

We could take days to go through your catalog, but I did want to touch on a few songs. It’s been said that that “Stone Cold Crazy” [from 1974’s Sheer Heart Attack] is a precursor to thrash metal. What were you guys thinking when you wrote it?

I can tell you exactly. Freddie wrote the lyric, and he already had a riff that he had played with his old band. I said, “That’s a great lyric and concept, but you need a better riff.” Freddie said, “OK, what do you got?” I started doing this frenetic riff to match the lyrics, and he really liked it. The whole band got into it, particularly Roger, because it’s very much based on the way he plays. It clicked quite quickly.

For some reason, we didn’t put it on the first album. We liked it, but we stuck it in a drawer thinking it would go on the second album. But that record was very highly arranged because we were consciously trying to push our music into a new place. Some people were pleased, but others weren’t. I remember getting a review in Australia saying, “Queen have abandoned their rock roots on Queen II.” I was shocked.

But that kind of response was an influence on Sheer Heart Attack, which was a deliberate attempt to recapture our original energy. We laid down “Stone Cold Crazy” very quickly, and we played it quickly. It’s one of the fastest tempos we’ve ever played. These days, if we play it on stage, we have fun with it. Sometimes we try to prove to ourselves that we can still flex our muscles at that rate, so it tends to get very fast. That’s when you have to pull it back, because it gets to the point where it loses its thump.

“The Prophet’s Song” appeared on 1975’s A Night at the Opera, but you were working on it at the time of Queen II.

I was. It was an obsession, and I’d been struggling with it. It did come from a dream — that isn’t a made-up thing. But I was trying to realize that dream, and I was having lots of problems with it. There were too many different bits, and it became a jumble.

I remember listening to Freddie playing “Bohemian Rhapsody” in Rockfield. He had a piano outside at one point, and I thought, “My God, he’s got this thing organized so perfectly, and here I am struggling with these different bits.” Eventually, I did pull it together, but I don’t know if it came to the optimum point, even in the end. Of course, it was never as successful as “Bohemian Rhapsody,” which became the prodigal child that has gone on to become immortal in so many ways. “The Prophet’s Song” is something Queen fans like, but it never conquered the world in the same way.

You mentioned James Burton, whom you emulate on “Crazy Little Thing Called Love.”

Oh, yes.

And there’s “Another One Bites the Dust.”

Yes, but the rhythm guitar isn’t me. John played the rhythm on that one. He obviously wrote the bassline and the whole thing. He was very insistent on getting his own touch with the rhythm, so that’s him on a Strat. I played all the heavy stuff, which wasn’t all that much. It just punctuates it. I have to tell you, getting that chunky rhythm feel is one of the hardest things I have to play live.

It’s very Nile Rodgers.

It’s very Nile Rodgers, and John absolutely adored him — we all do. John was very influenced by him, without a doubt. What an amazing guy Nile Rodgers is. He’s got his own vocabulary, his own world.

After Freddie’s passing, it took some time for Queen to tour again. How would you describe the differences between Paul Rodgers and how you now work with Adam Lambert?

It’s a good question. They’re both great, of course. We had a fantastic time with Paul. He has his own style, which we integrated into the band. But what happened was, there was a meeting point where we wanted to go deeply into his music — we were influenced by it in the first place. For me, it was a joy to play “All Right Now,” “Can’t Get Enough of Your Love” and all those things.

It became difficult as time went on, though. We would play South America, where people didn’t know that music, so we played more Queen songs. Paul dealt with it well, but I think it was hard for him to abandon a lot of his material. We really enjoyed it as an experiment, but as an experiment it had… limits. Eventually, we thought, “It’s probably gone as far as it can. Paul needs to get back to his own career.” Because he couldn’t just go on being the frontman of Queen. By mutual agreement, we thought, “That’s it.”

Now, with Adam, it’s a different story, because Adam can do all the stuff that Freddie did and more. It doesn’t matter what you throw at Adam — he can do it. He can do “Good Old-Fashioned Lover Boy” [from 1976’s A Day at the Races], which we wouldn’t dream of throwing at Paul Rodgers, because it just wouldn’t work. With Adam, it’s a different kettle of fish. He’s a born exhibitionist. He’s not Freddie, and he’s not pretending to be him, but he has a parallel set of equipment. He knows how to deal with an audience. He teases and taunts an audience quite naturally, without thinking about it. He loves to dress up. Although Paul did dress up a bit for us. We got a lot of sequins on him. [Laughs]

A little bit.

Adam lives and breathes that stuff. Adam is style, and that’s not to say he’s not content as well. He’s a born rock star and frontman, so it’s a very vibrant relationship we have with him. We treat Adam exactly the same as we treated Freddie in almost every way.

We talked about how you worked with Gwilym Lee, but what can we say about Rami Malek’s Oscar-winning performance as Freddie?

Ahh, Rami is such a phenomenon. He’s incredible. Rami became so Freddie-like in everyday life that we started to assume he was Freddie. It’s a really odd thing. That’s still the case. I mean, I think all the boys are great. The four of them, plus Lucy [Boynton, who portrayed Mercury’s longtime companion, Mary Austin] have become our extended family. We continue to spend a lot of time with them. It’s great.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.