Tom Petty: Tribute to an American Icon Who Made the Rock World a Better Place for 40 Years

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Musical artists who are huge in the heartlands tend not to do well with the critics. And vice versa. Critical faves rarely get their names and logos plastered on the bumpers and back windows of pickup trucks.

Tom Petty was the rare exception to that rule. When he left this life on October 2, felled by a heart attack at age 66, he left behind a body of work that distilled the raunchy, realist essence of rock itself—the urgent jangle and crackle of cranked-up guitars, the rebellious outsider attitude, the terse, laconic songcraft that encapsulated our dreams, despair, rage and moments of transcendent love. The music he made with his longtime band the Heartbreakers, with the rock superstar aggregate the Traveling Wilburys, on his own and with his reconstituted teenage bar band Mudcrutch, was universal in its appeal.

Everyone felt a kinship with Petty—alt rockers, metalheads, pop divas, rock icons, country artists, countless rank-and-file fans and, yes, rock critics. We all somehow felt like Petty was our guy—the one who spoke for us. That’s what it’s like when rock music is genuine.

“We were lucky,” Petty told me in 2002, referring to himself and the Heartbreakers. “We came up at a time where I always felt like I had some kind of relationship with the audience and the fans. They watched me grow up, and we have all been through different things together. And there was that third dimension of, ‘Well, I’m kinda interested in what’s on this guy’s mind right now. ’Cause I see him as my friend or someone that I know.’ I mean I felt like that about the Beatles and the Who. I was curious, ‘What’s Pete Townshend going to think about this?’ ”

While Petty’s music was rooted in the classic Sixties rock of the Beatles, Stones, Byrds, Who and Dylan, his fan base spanned every generation, from baby boomers to millennials. And he looked out for his fans, battling record companies to keep the price of his albums down in the Eighties, and forbidding concert promoters to offer elitistpriced “V.I.P. seating packages” at his concerts. At one venue, he personally carted away white-clothed V.I.P. tables from the area in front of the stage. He was more interested in donating money to charities and causes like Greenpeace, No Nukes, Fender Music Foundation and MusicCares than he was in overcharging his fans.

“We’re not Robin Hood,” he told me in ’02. “But so far we’ve been able to keep our ticket prices fairly reasonable.”

While Petty is gone, we’ll always have timeless songs like “Free Fallin’,” “American Girl,” “Refugee,” “I Won’t Back Down,” “Breakdown,” “Don’t Come Around Here No More,” “The Waiting,” “Don’t Do Me Like That,” “Runnin’ Down a Dream” and countless deep album cuts. There are plenty of the latter. It can truly be said of Tom Petty that he never put out a bad record.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

On one of those deep album cuts, “Dreamville” from 2002’s The Last DJ, Petty reminisced about his real-life home town, Gainesville, Florida, where he was born on October 20, 1950, and given the name Thomas Earl Petty. The song recounts the artist’s first life-changing encounter with rock and roll at age eight, at Glen Springs Pool in Gainesville. “That was the city pool,” he recalled. “They had one of the first outdoor jukeboxes I’d seen, with extension speakers. And it just rocked the place, and the music was really good. It’s one of the first times I really remember hearing rock and realizing I liked it.”

His next fateful encounter with rock took place in 1962, when Elvis Presley came to Gainesville to shoot scenes for his movie Follow That Dream. Twelve-year-old Tom was one of the onlookers. “Elvis really did mean a lot to me as a child,” Petty told me in 1999. “The whole idea that this person came from poverty like me, and he got out and made something of himself. And he did it by doing something pretty cool, rather than something that was devious, or being a crooked politician, or any of the normal Southern ways out of things.”

But it was the arrival of the Beatles and other British Invaders shortly thereafter that really lit the young Petty’s fuse. He started playing guitar and had joined his first band, the Sundowners, in the mid-Sixties. Around that time, he acquired his first 12-string guitar, something that would become a lifelong sonic signature for him. He was inspired by the Rickenbacker electric 12s played by the Beatles’ George Harrison and the Byrds’ Roger McGuinn, although it would take time for Petty to obtain one of his very own.

“My first Rickenbacker was a six-string,” he recalled. “The music store didn’t have a 12. That was around 1966 or 1967. And I got a Vox 12-string acoustic with a pickup, and that was actually a pretty good guitar. That’s where I kind of fell in love with the 12-string. The Byrds had a way of really featuring it, but the Beatles used it all the time too. I just thought it was a cool sound that it made along with a six-string. Then I got a Vox Phantom 12, because I couldn’t really afford a Rickenbacker at the time. So when I got a Rickenbacker 12 for the first time, it was probably in the Seventies somewhere. The Vox was pretty good, but not as sweetsounding as the Rick.”

Petty switched over to bass guitar in another one of his early bands, Mudcrutch, formed in 1970. The lineup included two musicians who would become lifelong Petty collaborators—guitarist Mike Campbell and keyboard player Benmont Tench. Mudcrutch built up a substantial following in Florida, then relocated to L.A. in the early Seventies, after scoring a contract with Shelter Records. Their one and only single, “Depot Street,” flopped. But Petty found a niche for himself in the L.A. music community as an apprentice songwriter working under producer Denny Cordell and artist/producer/tunesmith Leon Russell. While honing his own songcraft, Petty also received an education in the pitfalls of the music business.

“We really saw the bullshit firsthand,” he recalled. “Groups that show up and ride around in limos on their first album, and have huge industry parties. And they’re terrible, and everybody knows it’s not gonna happen. Everybody but them. And we saw people that got sold on a gimmick: ‘If y’all dress up this way and do that…’ We knew not to do it. Like, ‘I’m not getting in any suit of clothes. I’m not joining anybody’s club. We’re just gonna do our thing.’ ”

Shelter tried packaging Petty as a solo artist, pairing him with backing musicians. With his blond good looks, it might have worked. But Petty was determined to make music with his own band, like so many of his heroes. So he got Campbell and Tench back in the picture and formed the Heartbreakers in 1975, recruiting two other Gainesville musicians—drummer Stan Lynch and bassist Ron Blair—to complete the lineup. Blair had played in a Gainesville group called RGF, which Petty described as “Mudcrutch’s biggest competition.”

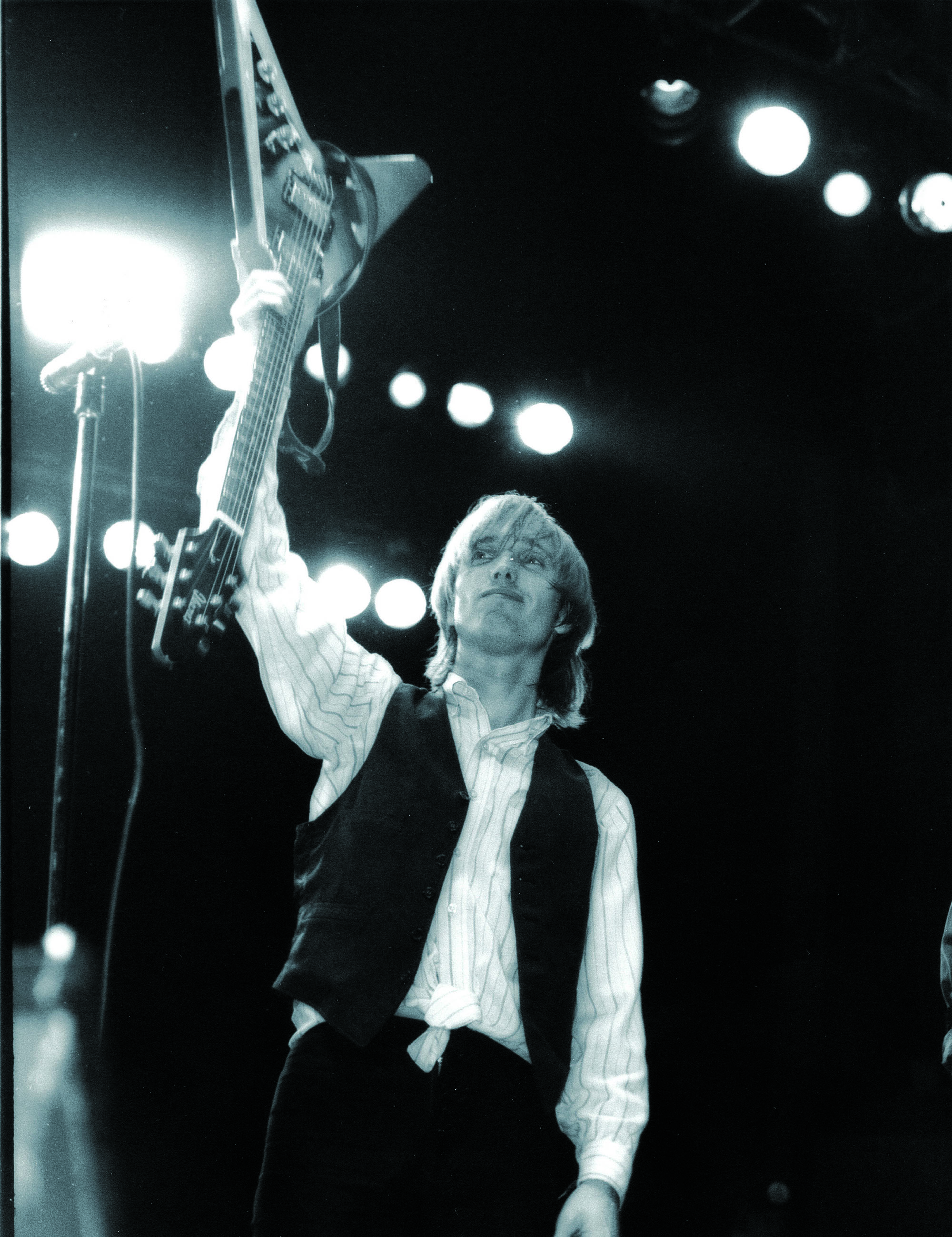

Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers’ self-titled 1976 debut LP was everything a rock and roll album should be—10 punchy, well-built tunes delivered by a band that was super tight from playing countless bars and clubs, yet still fired up with the hunger and energy of youth. The 12-string clangor of the disc’s second single, “American Girl,” caused the Byrds’ Roger McGuinn to remark, “Now when did I record that?” when the record was first released.

But the song is pure Petty. Throughout his career, he forged a unique way of writing about female characters. The typical Petty heroine is a young woman itching to break free of the confines of her small town. The theme is reflective of Petty’s own ambitions to bust out of Gainesville, but the feminine angle added a new dimension.

“I always just thought that was really romantic when I was younger,” he told me in ’99. “I’ve always loved girls, and I found they were interesting characters to write about—maybe more so than men. It comes easier for me to write about female characters. And when we were starting out, you didn’t hear many positive songs about girls. There were a lot of songs about girls, but a lot of times they kind of put them down. They didn’t come off too strong. And somewhere along the line, around the first or second album, I started to write songs that kind of gave them a positive image.”

The album’s first single, “Breakdown,” made it to the bottom of the Top 40 in the U.S. But the release of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers coincided with the outbreak of punk and new wave in the latter half of the Seventies. Like many new wavers, Petty and his band were drawing inspiration from rock and roll’s mid-Sixties golden era. Their concise songcraft and no-frills, two-guitar aesthetic also seemed to be coming from the same place as punk and new wave’s rebellion against the bloated, self-indulgent excesses of Seventies corporate rock. So at first, Petty and his band were often lumped in with the new wave, which actually gave the fledgling Heartbreakers’ career a lift. This is where they found many of their early listeners.

“It was unusual being lumped in,” Petty later said. “But it felt better than being lumped in with the other side! We agreed with [the new wave bands] in spirit. Music had gotten really bad in our view, and we hated seeing stuff we believed in watered down and crassly commercialized. But we never thought we were [new wave]. And we never tried to embrace it. But it felt pretty cool to be alternative, you know? And it kind of hurt when we got really popular and it felt like, ‘They see us as rich people now.’ But really, we hadn’t changed.”

It took a little while longer for them to get really popular, however. Petty was battling with Shelter Records for a better financial deal around the time of the Heartbreakers’ second album, You’re Gonna Get It! This wouldn’t be the last time he went head-to-head with the music-biz money men. Beneath his laid-back exterior, there was a tough inner-core—an unwavering dedication to fair play and basic human decency. Further contractual hassles delayed the release of the album that became Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers’ commercial breakthrough in 1979, Damn the Torpedoes. Two singles, “Don’t Do Me Like That” and “Refugee,” climbed to the top of the charts.

Petty was no longer just an artist for new wave sophisticates. He now belonged to everyone. “Refugee,” in particular, is a distillation of everything great in rock history up to that point. Dylan-esque verses tumble out with declamatory urgency, leading to a defiant, yowling, chorus redolent of outsider anthems like the Kinks’ “I’m Not Like Everybody Else” or the Animals’ “It’s My Life.”

By posing with a solidbody Rickenbacker 625 12-string guitar on the Torpedoes cover, Petty—along with R.E.M.’s Peter Buck and the Jam’s Paul Weller—sparked renewed interest in Rickenbackers and the electric 12-string sound in general. He’d become that influential. But success brought more battles. Petty’s record company wanted to jack up the price of his next album, Hard Promises, from $8.98 to the label’s “superstar price” of $9.98. He dug in his heels and told them “hell no,” threatening to title the disc The $8.98 Album. In the end, MCA Records (Shelter’s parent label) relented. They were one of several corporate entities who discovered that, for Petty, “I Won’t Back Down” wasn’t just a song. It was a way of life.

Throughout the Eighties Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers continued to evolve without losing their edge. 1985 found them working for the first time with producer Dave Stewart, who’d risen to fame as one half of Eurythmics. The result was Southern Accents, originally conceived as a concept album ruminating on Petty’s Southern roots. But the way forward wasn’t always clear, as is often the case when an artist casts about for a new direction. At one point during the tortuous creative process, Petty famously punched a recording studio wall in frustration, fracturing his left hand.

“At that time, the Heartbreakers were looking for something new,” he later said. “We felt like we’d taken the Big Jangle as far as we could. I liked Dave [Stewart] because he just had no reverence for anything, which helped shake me out of what I was doing and go somewhere else.”

Stewart was Petty’s neighbor at the time in the L.A. suburb of Encino in the San Fernando Valley. The two men co-wrote Southern Accents’ biggest hit and one of Petty’s most iconic songs, “Don’t Come Around Here No More.” The track’s trippy, somnambulant electric sitar, played by Stewart, contrasted effectively with the lyric’s “Positively 4th Street” vitriol. It was something new, but still unmistakably Petty.

High-powered collaborations would loom large in Petty’s career from this point onward. He had known Bob Dylan since the late Seventies. But in 1986, Petty and the Heartbreakers began touring with Dylan as his backing band.

“I think I really understood what Bob wanted to do at the time,” Petty later said, “and I got off on it a lot. Like, ‘Hey, we’re Bob Dylan’s band and we’re gonna lay it down tonight.’ ”

George Harrison was another musical legend that Petty had known since the Seventies. His longstanding friendships with Harrison and Dylan led to his inclusion in the Traveling Wilburys, the supergroup that also included mid-Sixties icon Roy Orbison and producer/Electric Light Orchestra (ELO) mastermind Jeff Lynne. The billion-dollar quintet recorded its self-titled debut album, Traveling Wilburys Vol. 1, in 1988. Orbison died shortly thereafter. But the four remaining icons released a second LP, whimsically titled Traveling Wilburys Vol. 3, in 1990.

Petty’s membership in the Wilburys confirmed his role as keeper of the flame—the younger artist carrying on the great rock tradition that giants like the Beatles and Bob Dylan had forged in the Sixties. The torch had officially been passed.

“They treated me equally, which was nice,” Petty said of his time as a Wilbury. “But I always felt like I was the kid in the band. I was the one who was lucky to be there. But they never treated me that way.”

Harrison would remain a close friend and occasional Petty collaborator for the remainder of his life. “Me and George have something somewhere where we’re connected,” Petty said. “Some past life or something.”

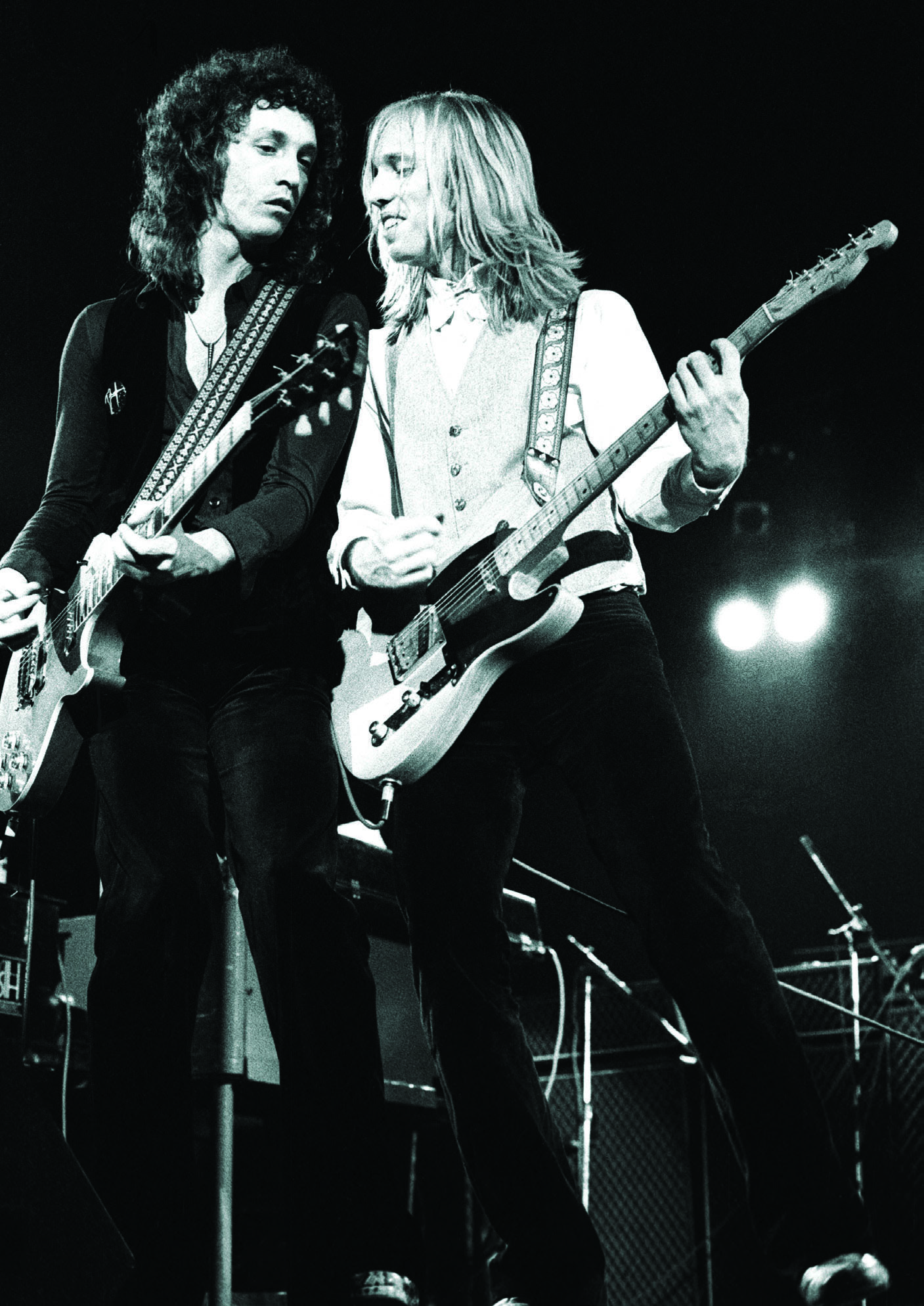

Petty selected Jeff Lynne to co-produce his debut solo album, 1989’s Full Moon Fever. While nominally a solo album, it also includes input from several Heartbreakers, including Benmont Tench and bassist Howie Epstein, who had replaced Ron Blair in 1982. But the Heartbreaker who played the most prominent role on the disc was Mike Campbell, who served as co-producer, lead guitarist and multi-instrumentalist.

“Mike’s so much better than me on lead guitar,” Petty said of his longtime collaborator. “I kind of specialize in rhythm. And over the years, I’ve kind of gotten used to singing and playing rhythm. If I have to play a specific line, it’s better that I’m not singing, so I can actually put my mind on what I’m going to play. But most of the time, I play rhythm, although they let me play more and more solos as time goes on.”

Full Moon Fever yielded two more of Petty’s landmark tracks, “Runnin’ Down a Dream” and “Free Fallin.’ ” The latter song, wistful and acoustic guitar-driven, is quintessential Petty—another female protagonist, this time an Eighties L.A. “valley girl,” and a narrative that name checks locations around Petty’s home in the San Fernando Valley. Like a number of Petty songs, “Free Fallin’ ” employs essentially the same chord progression for the verses as the choruses. He doesn’t need different or extra chords to drive home the song’s anthemic chorus. All he has to do is shift his voice into its spine-chilling upper register.

Petty’s genius as a songwriter resided in his ability to pack a wealth of both ambivalence and resonant meaning into a simple four-word, three-chord chorus: “And I’m free, free-fallin’.” Is it a declaration of freedom, or a cry of outsider despair? Maybe both. Like all great songs, it leaves space for you to find your own way inside.

Petty went through a rough patch in the Nineties. Following his 1996 divorce from Jane Benyo, to whom he’d been married since 1974, he fell into a deep depression and heroin addiction. He’d eventually recover from both, but the despair of this dark period is eloquently captured on his 1999 album Echo. It marked his return to the Heartbreakers after a pair of solo discs and a film soundtrack disc that he later regretted, Songs and Music from “She’s the One.”

By the dawn of the 21st century, Petty was back in fighting form, having kicked heroin and married Dana York—a union that would last until the end of his life. And “fighting form” is an apt term for the mood of his and the Heartbreakers’ masterful 2002 album The Last DJ. The record takes on the predatory greed that had decimated both the music businesses and American society at large in the early years of the new century.

Lines from the title track such as “they can’t turn him into a company man, they can’t turn him into a whore,” are as applicable to Petty himself as they are to the album’s protagonist, an independent-minded radio disc jockey who gets fired because he “says what he wants to say” and “plays what he wants to play.” In the wake of Petty’s passing, the song’s chorus tag line seems particularly poignant: “there goes the last human voice.”

His final decade was productive. In 2007 he re-convened his old band from the Gainesville days, Mudcrutch. Original members Tom Leadon and Randall Marsh were brought out of retirement to join forces with Petty, Campbell and Tench for two albums, Mudcrutch 1 and Mudcrutch 2, in 2008 and 2016 respectively. In this period, Petty also hosted his own Sirius radio programming—another way of connecting his fans with the classic rock music he loved. There was one more solo album, Highway Companion (2006) and two more Heartbreakers discs, Mojo (2010) and Hypnotic Eye (2014), not to mention a full touring schedule, which generated a substantial body of live albums.

Anyone fortunate enough to have seen Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers in concert knows that they never failed to deliver—performing with the precision that comes from decades of playing together, yet infusing each note with a lifetime’s worth of passion and dedication. Just a week before his passing, Petty completed the last date of what he said would be his final major tour. It was a triumphant hometown gig at the Hollywood Bowl. The night ended with “American Girl.”

For a rock performer to obtain Petty’s level of success yet still manage to keep it real for four decades is a signal achievement. In 1999, Petty told me his secret for doing so:

“I never have surrounded myself with very much posse,” he said. “I’ve seen artists go really wrong by having a lot of people around that keep the myth inflated. I’ve tried to stay with people who treat me fairly normally. It’s a drag not to be treated normally. I guess there’s people who love that, and really come to life in those kinds of situations. I don’t. I shrink from it. It makes me uncomfortable. I mean, I’m really glad for the success I’ve had. I think I would have been very disappointed if it didn’t happen, and thought, Shit, I shoulda been famous. But it really is a double-edged sword.”

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.