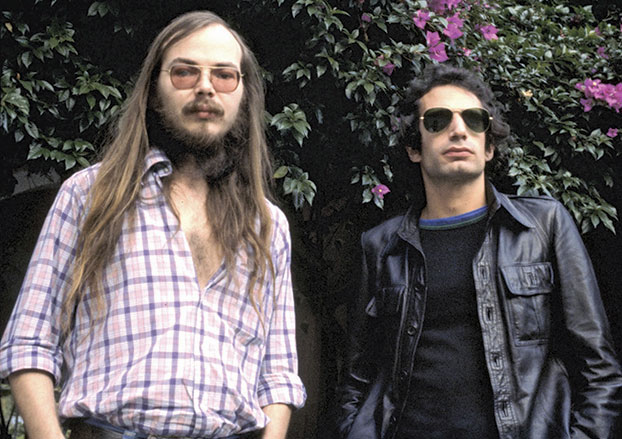

Walter Becker (1950-2017): Paying Tribute to the Steely Dan Legend and Reluctant Guitar Hero

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Reclusive, elusive and sardonically self-effacing, Walter Becker was not your typical guitar hero.

He often shunned the limelight and kept mum about the details of his enormous contributions to the game-changing music of Steely Dan, his own solo recordings and the records he produced for other artists, such as Rickie Lee Jones, China Crisis and his longtime musical partner Donald Fagen.

Becker died much as he had lived, slipping away quietly on the Sunday before Labor Day on the Hawaiian island of Maui, where he’d made his home for many years. He was 67 years old at the time of his passing.

The cause of his death was not given. But his die-hard fans knew something was amiss when Becker was unable to appear with Steely Dan for this summer’s Classic West and Classic East concerts, the blockbuster shows that teamed Steely Dan with fellow Seventies hitmakers the Eagles, Fleetwood Mac, the Doobie Brothers, Earth Wind & Fire and Journey. All that was said officially at that time was that Becker was recovering from “a procedure.”

If Becker was a guitar hero, he wasn’t the kind who said it all with his ax. He also contributed substantially to Steely Dan’s glib, evocative, sophisticated lyrics. An adept producer and arranger, he played a number of instruments besides the guitar. All of his musicality grew out of the innovative songcraft he forged with Steely Dan vocalist/keyboardist Donald Fagen.

The band was known for working with a legion of legendary session guitarists—Larry Carlton, Lee Ritenour, Dean Parks, Hugh McCracken, Paul Jackson Jr., Rick Derringer and others. But it was often Becker who was able to provide just the right rhythm or lead part to suit the complex mechanics of a Steely Dan arrangement.

His solo playing can be heard on key Steely Dan tracks such as “Josie,” “Hey Nineteen,” “Gaucho” and “Black Friday.” Not that he’d ever call your attention to that. Becker was the antithesis of the stereotypically egocentric guitar man. And much of his greatness lies in that very fact.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“It wouldn’t bother me at all not to play on my own album,” Becker told rock journalist Cameron Crowe in 1977.

The singer and songwriter Rickie Lee Jones first met Becker when he produced her 1989 album Flying Cowboys. In a statement issued after his death, she remembered Becker as being “rather delicate looking. And he had a soft energy, nothing like what I thought I saw in the pictures. A softy. A recovering addict. Hey, me, too. He knew more about music right off the bat than anyone I had met in a long time. He didn’t patronize, he didn’t condescend, not even a tiny bit, not for one moment.”

Becker was a New Yorker by birth, and there was plenty of New York attitude in his wiseguy wit. He started out playing saxophone but soon switched to guitar. Early on, he learned some blues licks from guitarist Randy Wolfe (a.k.a. Randy California) who would go on to found Spirit. But in 1974, Becker gave Rolling Stone magazine a different account of his early musical training:

“I learned music from a book on piano theory,” he said. “I was only interested in knowing about chords. From that, and from the Harvard Dictionary of Music, I learned everything I wanted to know.”

It was most likely the blues guitar thing, however, that caught the ear of Donald Fagen in 1967, when he and Becker were students at Bard College, an arty enclave just north of Manhattan, on the Hudson River. “I hear this guy practicing,” Fagen said of Becker, “and it sounded very professional and contemporary. It sounded like, you know, like a black person, really.”

The two students became close friends and almost immediately started writing songs together. In a tribute to Becker issued shortly after his passing, Fagen offered some details: “We started writing nutty little tunes on an upright piano in a small sitting room in the lobby of Ward Manor, a moldering old mansion on the Hudson River that the college used as a dorm. We liked a lot of the same things: jazz (from the Twenties through the mid-Sixties), W.C. Fields, the Marx Brothers, science fiction, Nabokov, Kurt Vonnegut, Thomas Berger and Robert Altman films come to mind. Also soul music and Chicago blues.”

Becker left Bard in 1969, without taking a degree, and joined Fagen in New York with an eye toward getting into the music business. They served as backing musicians for vocal group Jay and the Americans, wrote the soundtrack for Richard Pryor’s 1971 film You Gotta Walk It Like You Talk It or You’ll Lose that Beat, and landed one of their songs, “I Mean to Shine,” on a Barbra Streisand album.

A gig as staff songwriters for ABC Records brought them out to L.A. at the dawn of the Seventies. But they soon realized that much of their music was too complex for most other artists to record.

So they decided to put together their own band, appropriating the name Steely Dan from the fictitious brand name of a dildo “Steely Dan III from Yokahama” in the William Burroughs novel Naked Lunch. Becker was on bass in the original lineup, with Jeff “Skunk” Baxter and Denny Dias sharing guitar duties.

Steely Dan’s 1972 debut album, Can’t Buy a Thrill, captivated FM album rock radio instantly, with the standout tracks “Do It Again,” “Reelin’ in the Years” and “Dirty Work.” It was soon followed by Countdown to Ecstasy (1973) and Pretzel Logic (1974), which yielded further album rock radio staples such as “Bodhisattva” and “Rikki Don’t Lose that Number.”

These recordings brought a new sound and style to early Seventies pop and rock music. Steely Dan’s first album essentially marked the debut of “adult rock.” The chord progressions and arrangements had an aura of jazz sophistication, while the lyrics had a literary quality—allusive and cryptic, peopled by outsiders, losers, criminals, gamblers, party girls and other characters that might have stepped out of a 20th-century American novel.

This kind of lyric writing had hitherto been more associated with songsmiths, such as Bob Dylan or Paul Simon, rooted in the less harmonically complex folk tradition. Either that or the three-chord rock and roll of working class poets like Bruce Springsteen. Steely Dan’s juxtaposition of musical and lyrical sophistication was something else again.

“The ‘anarchists,’ or people who are interested in more interesting lyrics, are, generally speaking, not interested in jazz harmonies,” Becker said in an interview. “They want something more raw and what they perceive to be subversive-sounding, which usually means clanging guitars. We thought superimposing jazz harmonies on pop songs was subversive.”

Becker plays his Hahn Guitars Model 229 at the 2015 Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival in Indio, California (photo: Chelsea Lauren/Getty Images)

In her own tribute to Becker, Rickie Lee Jones wrote that Steely Dan “introduced a new idea into the musical conversation of the time. It was the idea that intelligent music was cool. In a year where drum solos lasted minutes, quarter hours even, and singers screamed—a lot—Steely Dan made it cool to be educated. It is safe to say that they are the beginning of college rock.”

At the same time, though, Becker was quick to distance himself and his band from the jazz-rock-fusion scene also ascendant in the early Seventies through the work of guitarists such as John McLaughlin and Al Di Meola.

“I’m not interested in a rock-jazz fusion,” Becker said in 1974. “That kind of marriage has so far only come up with ponderous results. We play rock and roll, but we swing when we play. We want that ongoing flow, that lightness, that forward rush of jazz.”

The aforementioned Pretzel Logic was the first album to feature Becker on guitar. He’d entrusted the bass role to a top L.A. session musician, saying, “Once I met Chuck Rainey, I felt that there was really no need for me to be bringing my bass guitar to the studio any more.” Becker can be heard soloing on Steely Dan’s interpretation of the Duke Ellington/Bubber Miley jazz composition “East St. Louis Toodle-Oo” from Pretzel Logic, using a talk box on his guitar to get a trombone like-timbre.

From this point onward, Steely Dan would enter a new career phase. All members but Becker and Fagen eventually left the fold, touring was suspended indefinitely and Steely Dan became solely a recording entity. Becker and Fagen forged a role as studio auteurs, crafting intricate musical arrangements and directing a cadre of L.A.’s top session musicians in the realization of pristine, highly polished album tracks.

This approach led to the creation of 1976’s The Royal Scam and 1977’s Aja. The latter album, in particular, represents the apotheosis of Steely Dan’s studio artistry. It was the group’s best-selling album and their first LP to go Platinum. Album tracks like “Aja,” “Deacon Blues” and “Josie” are still revered by guitarists and other musicians today.

But Steely Dan also had their critics as the Seventies drew to a close. Their perfectionist studio approach was derided as being too slick. Steely Dan got lumped in with L.A. “Mellow Mafia” acts such as the Eagles and Jackson Browne, and that was not a flattering comparison at the time. For some, their music came to personify the worst aspects of L.A.’s laid-back, materialistic “hot tub” culture. Their plush, loungy aesthetic was dismissed as a prime example of the “818 Area Code Sound”—a somewhat contemptuous reference to the telephone exchange for L.A.’s sheltered, suburban San Fernando Valley. Punk rock had arrived, causing a seismic shift in the valuation of rock song-craft and performance.

And all this coincided with a series of professional and personal crises for Steely Dan, and Becker in particular. Work on Aja’s follow-up album, Gaucho, was hampered by technical difficulties, record company hassles and Becker’s escalating heroin addiction.

On January 30, 1978, Becker’s girlfriend, Karen Roberta Stanley, died of a drug overdose in his Manhattan apartment. This led to a $17 million wrongful death lawsuit against the guitarist, which was settled out of court. Shortly after this, Becker was hit by a New York taxicab, which fractured his right leg in several places. In the face of all this adversity, Fagen and Becker pulled the plug on Steely Dan not long after the release of Gaucho in 1980. Becker retired to the Hawaiian island of Maui where he turned his attention to avocado farming and acting as what he called “a self-styled critic of the contemporary scene.”

During these years of recovery and recharging, he was a bit less prolific than Fagen, but hardly a hermit. Becker released two well-received solo albums, 1994’s 11 Tracks of Whack (which has 12 songs) and 2008’s Circus Money. He also emerged as a record producer in his own right, attaining significant chart success with his work for the British group China Crisis. But it was his production work on Fagen’s 1993 solo disc Kamakiriad that would lead to the reformation of Steely Dan.

This time, the duo embraced live performance wholeheartedly, touring with a new lineup in support of the 1993 career retrospecive box set Citizen Steely Dan. These dates would produce the 1995 live set Alive in America.

Becker and Fagen released a new Steely Dan studio album, the Grammy-winning Two Against Nature, in 2000. It had been two decades since the last Steely Dan studio disc, and the album was enthusiastically embraced by a new generation of fans, as well as the group’s original fan base.

A second studio disc, Everything Must Go, appeared in 2003. These recordings, combined with Becker’s solo recordings and live work with Steely Dan, shed fresh light on his guitar playing and overall musical mastery. In his eulogy to his musical comrade, Fagen summed up Becker’s contribution to popular music succinctly and accurately, stating, “he was smart as a whip, an excellent guitarist and a great songwriter.”

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.