How 1970's 'Workingman’s Dead' Changed the Grateful Dead Forever

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What a difference a year makes. In February 1969, the Grateful Dead recorded a series of shows at San Francisco’s Avalon Ballroom and Fillmore West in the hope of finally capturing on tape the psychedelic alchemy of their already legendary onstage interplay.

The double album Live Dead, released in November that year, showcased the Dead at their adventurous and exploratory acid-peak best and cemented their reputation as the premier jamming band of the era. Yet exactly one year later, in February 1970, the group ambled into a recording studio and, in a single week, cut an album that was Live Dead’s polar opposite.

With its concise songs, bright harmonies and folk and country trimmings, Workingman’s Dead felt almost like the work of a completely different band—a stylistic shift as radical as when the Beatles followed Rubber Soul with Revolver. It was made with little overt commercial intent, but Workingman’s Dead instantly became the best-selling album of the Dead’s five-year career, and it set the band on a course that would eventually make it one of the most popular acts America ever produced, with a devoted fan base second to none.

Until Workingman’s Dead, the Grateful Dead’s studio output had been largely ignored by the record-buying public. That album’s immediate predecessor, Aoxomoxoa, released in June 1969, was a carefully crafted effort full of intricately arranged songs brimming with playful, colorful and at times impenetrable lyrics dense with hallucinatory imagery.

The recording sessions were long and expensive, and though the album contained a few future Dead classics—most notably “St. Stephen” and “China Cat Sunflower”—in the end it never really found a wide audience. Compared to the group’s live performances, it felt stiff and mannered. Live Dead addressed that dilemma beautifully and was still picking up steam in the winter and spring of 1970, winning new converts to the Dead’s uniquely trippy mélange, when suddenly a completely different-sounding Grateful Dead started popping out of a million radios.

The song was “Uncle John’s Band,” and instead of molten electric guitars and bass in epic flight over the crashing and cracking drums and cymbals of two percussion powerhouses, the song had a warm and intimate acoustic glow. The voices of guitarists Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir and bassist Phil Lesh rose in bright harmony, and lyricist Robert Hunter’s words exuded a gentle homespun wisdom: “Well, the first days are the hardest days/Don’t you worry any more/’Cause when life looks like easy street/There is danger at your door…”

Could this really be the notoriously off-key-singing and lyrically opaque Grateful Dead? It was, and much of the rest of the album that “Uncle John’s Band” kicked off, Workingman’s Dead, reinforced the group’s apparent transformation from blazing psychedelic astronauts to rootsy troubadours steeped in folk and country music. The infectious country-rock anthem “Casey Jones”— famous for its daring chorus: “Driving that train, high on cocaine, Casey Jones you better watch your speed”—would follow “Uncle John’s Band” as an FM radio hit that year, and both the rollicking country-bluegrass-rock fusion “Cumberland Blues” and the simmering rocker “New Speedway Boogie” were also popular radio numbers.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

After years of fringe success, the Dead had truly entered the rock mainstream. It was not, however, an overnight change in direction for the band. For one thing, the Dead already had strong roots in folk and country. In his pre-Dead days, Garcia had been in a succession of acoustic groups that played old-time country, bluegrass and traditional folk music, and Weir had been a fan of the popular folkies of the early Sixties, like the Kingston Trio and Joan Baez, and also learned to play some country blues.

Their first group together, in 1964, Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions, drew from those worlds and added a dash of acoustic rock and roll, while Ron “Pigpen” McKernan brought in a cool blues sensibility. When those three started an electric band, the Warlocks, in the spring of 1965—adding Bill Kreutzmann on drums and, fairly quickly, Lesh on bass—some of the old folk/country repertoire came with them, including “Cold Rain and Snow,” “I Know You Rider,” “Stealin’ ” and “Don’t Ease Me In.”

Those types of songs stayed in the Dead’s repertoire during the group’s halcyon days in the San Francisco ballrooms. But as they developed their songwriting chops during the second half of 1967 and through 1968, their sound increasingly moved away from their original influences and toward more complex structures, unusual time signatures and open-ended jamming that drew more from Indian music (partly the influence of drummer Mickey Hart, who joined in the fall of 1967) and jazz. Short songs were few and far between as the Dead developed and perfected their uncanny ability to stitch songs and jams together with what sometimes seemed to be magic Day-Glo thread.

The fall of 1968 through the spring of 1969 marks the Dead’s fiercest, most confident and accomplished psychedelic playing, reaching its apex around the time that Live Dead was recorded at the Avalon Ballroom and the Fillmore West. But changes were on the way. Perhaps the harbinger of the future direction was a song on Aoxomoxoa called “Dupree’s Diamond Blues,” Hunter and Garcia’s clever recasting of a popular story-song that originated in the early Twenties.

It’s a relatively straight narrative song with roots in blues and early 20th century pop tunes, driven by acoustic guitars. “Hunter and I always had this thing where we liked to muddy the folk tradition by adding our versions of songs to the tradition,” Garcia told me in 1989. “We had our ‘Casey Jones’ song [on Workingman’s Dead]. We had our ‘Stagger Lee’ song [on Shakedown Street, 1978]. ‘Dupree’s Diamond Blues’ is another of those. It’s the thing of taking a well-founded tradition and putting in something that’s totally looped.” Musically, he added, “it has a kind of carnival or medicine show kind of feel, and also a ragtime feel.”

By February 1969, Garcia and Weir occasionally broke out acoustic guitars onstage to perform “Dupree’s,” followed by another Aoxomoxoa tune based around acoustic guitar, “Mountain of the Moon.” But leave it to Garcia and the Dead to then figure a way to segue that second acoustic number right into the trans-galactic flow of that era’s grandest improvisational piece, “Dark Star.”

For his part, Hunter, who also had a deep background in older folk music styles, found himself being increasingly drawn to the Band. Their brilliant first two albums, 1968’s Music from Big Pink and 1969’s The Band (a.k.a. The Brown Album) had drawn from a multitude of early American music styles and fused them into an utterly distinctive and original rock amalgamation.

As Hunter noted in an interview I did with him in 1988, “The direction [leader/songwriter Robbie Robertson] went with the Band was one of the things that made me think of conceiving Workingman’s Dead. I was very much impressed with the area Robertson was working in. I took it and moved it to the West, which is an area I’m familiar with…regional but not the South, because everyone was going back to the South for inspiration at that time.”

It’s unclear to what degree the Dead’s turn in a country direction might have been influenced by their move out of San Francisco’s crumbling Haight-Ashbury district in mid 1968 to more rustic Marin County, north across the Golden Gate Bridge. Mickey Hart settled on a Novato ranch that had a barn and horses, and the others spread out in nearby towns. Hunter and Garcia (with his lady love, Mountain Girl) rented a large but modest house in the southern Marin town of Larkspur, and over the course of about a year, churned out one fantastic song after another.

Hunter often typed lyrics day and night and fed them to Garcia, who would quickly set them to music, sometimes within hours of their delivery. This is where the songs for Workingman’s Dead were born—“glorious days,” as Hunter said. Country flavors had been creeping into rock and roll in general for quite some time. Buffalo Springfield had a strong country and folk undercurrent in some of their material, as did the Byrds, Moby Grape and, by 1968, the Rolling Stones on Beggar’s Banquet.

That same year, Dylan went back to acoustic music on John Wesley Harding, followed in 1969 by the more overtly country Nashville Skyline. Meanwhile, the Flying Burrito Brothers and Poco had helped put country-rock on the map. Even though the Dead were playing some of their most challenging and adventurous psychedelic music during this period, offstage Garcia and Weir were listening to country music mostly. Garcia was increasingly being influenced by guitarists from the “Bakersfield school” of country music, such as Roy Nichols (of Merle Haggard’s group, the Strangers) and Don Rich (of Buck Owens’ Buckaroos), both tasteful and soulful string-benders.

In March 1969, at the end of a tour, Garcia bought a Zane Beck pedal-steel guitar at a music store in Colorado, and it wasn’t long before he brought the pedal steel onto the stage. At first, Garcia backed a country music–loving singer and songwriter named John “Marmaduke” Dawson in a tiny club south of San Francisco. Then, the fearless Garcia played it occasionally with the Dead on a range of country songs.

A few months later, Marmaduke and Garcia formed the country-rock New Riders of the Purple Sage, with Garcia on steel for the first year-plus. (Incidentally, with the Dead in this era, Garcia mostly played a mid-Sixties red Gibson SG—that’s his Live Dead ax—through his trusty Fender Twin Reverb amps, but also occasionally employed a sunburst Stratocaster. Weir favored a Gibson 335 or 345 through a pair of Twins.) In June ’69, the first three Hunter-Garcia songs that would eventually find a home on Workingman’s Dead were introduced.

“Dire Wolf” came first, a dark but whimsical tale about a man who invites a wolf into his desolate cabin in the woods for a game of cards, possibly to determine whether the wolf will eat him or not. “Don’t murder me,” the storyteller begs, but the cards are clearly not falling his way. Musically, it’s a simple folk song, and some of the early live versions were sung by Weir, with Garcia adding steel accompaniment.

Soon, though, Garcia reclaimed it, and on occasion in 1969 he would suggest that the crowd sing along on the chorus. “Casey Jones” was the next new tune to emerge from the Larkspur songwriting sessions, and though Garcia’s original acoustic guitar-voice demo from early June is strikingly similar to the way it ended up on Workingman’s Dead, the first several Grateful Dead versions in early summer ’69 have a different vibe.

The main rhythm has an almost Motown feel to it (think “I Second That Emotion”), and there are a couple of fairly lengthy guitar extrapolations. It wouldn’t be too long, however, before the song found its finished form. A day after the debut of “Casey Jones” came “High Time,” a gorgeous bittersweet ballad that easily could have come from George Jones, Merle Haggard or any number of other country greats. Garcia once complained that he felt could never quite do the song justice as a singer, but from mid 1969 through mid 1970, it became an important cornerstone of the band’s repertoire, often serving as a nice, grounding contrast to spacey songs such “Dark Star” and “That’s It for the Other One,” or the spunky combo of “China Cat Sunflower” and “I Know You Rider.”

The Pigpen-sung “Easy Wind,” written by Hunter alone, started turning up in August 1969. Pig is convincing as a hard-workin’, hard-drinkin’ road laborer “chippin’ them rocks from dawn ’til doom/While my rider hide my bottle in the other room.” From the outset, the song featured slashing guitar counterpoint lines from Weir and Garcia and a funky R&B feel. It’s a perfect vehicle for Pig, who during this period mostly sang cover tunes, from Otis Redding’s “Hard to Handle” to the Olympics’ “Good Lovin’ ” to “Lovelight.”

The final burst of new Workingman’s Dead songs arrived in November and December 1969, ironically, right after the release of Live Dead, which had virtually no overt country and folk textures. Musically, Garcia described the spry and speedy “Cumberland Blues” (which he co-wrote with Phil Lesh) as a blend of Bakersfield country and up-tempo bluegrass.

Lyrically, Hunter paints a picture of a coal miner’s woes in and out of the mines. Like the other new songs, it took the Dead’s fans to some completely new places that, miraculously, fit in with all the other, stranger spaces their earlier material occupied.

“Black Peter” was a dire Hunter-Garcia folk blues about a man on his deathbed, while “Uncle John’s Band” was an upbeat anthem that became an instant favorite of everyone who heard it. The influence of Crosby, Stills & Nash—friends of the Dead’s whose harmony-filled first album had been ubiquitous since the summer of 1969—was obvious, and though the Dead weren’t at that level as singers, they had an undeniable vocal chemistry, and that song, in particular, had a reassuring glow that drew listeners in, made them feel that they too were maybe part of “Uncle John’s Band.”

The last Workingman’s song to be born was “New Speedway Boogie,” Hunter’s somewhat enigmatic commentary on the early December 1969 Altamont Speedway Free Festival. The event—a West Coast version of Woodstock—was marred by violence, including the death of concertgoer Meredith Hunter by a member of the Hells Angels, who were there to provide security. “New Speedway Boogie” rumbles along ominously—a modified shuffle/boogie—as Garcia sings in broad metaphorical terms about harsh realities, lessons learned (or not) and the broader takeaway: “One way or another, this darkness got to give…”

By the time “Speedway” was introduced, the Dead had already decided to make an album in the winter of 1970, cutting at Pacific High Recording, a relatively new addition to the San Francisco recording landscape. They had spent many months and more than $100,000 of Warner Bros.’ money making Aoxomoxoa, so this time they were determined to take their relatively simple and straightforward new songs and record them as live as possible in the studio.

“Workingman’s Dead was done very quickly,” producer/engineer Bob Matthews told me in 2004. (Matthews’ familiarity with the band extended all the way back to the Mother McCree’s days with Garcia, Weir and Pigpen.)

“We went into the studio first and spent a couple of days rehearsing—performing—all the tunes, recording them onto two-track. When that was done, I sat down and spliced together the tunes—beginning of side one to end of side one, beginning of side two to end of side two. I got that idea from [the Beatles’] Sgt Pepper’s: ‘Before we even start, let’s have a concept of what the end product is going to feel like, sequencing-wise.’ They rehearsed some more in their rehearsal studio, and then they came in and recorded [on one of Ampex’s new 16-track machines]. But at all times there was the perspective of where we were in the album.”

The Dead had further honed their chops by playing a series of acoustic sets during the winter of 1969–1970, mixing versions of their new songs among folk and country covers. The entire album was recorded and mixed in about 10 days. Overdubs included Garcia’s pedal-steel parts, Pigpen’s harmonica, various acoustic and electric guitar parts and, of course, the vocals, which were certainly at a level the Dead had never achieved before.

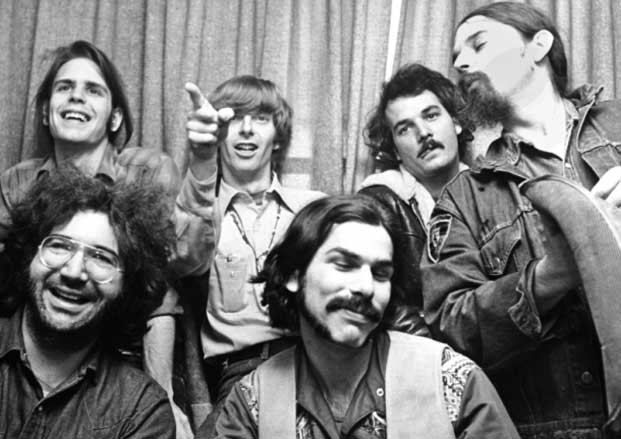

The noted San Francisco poster artist Stanley Mouse and his partner Alton Kelley conceived of the now-iconic front cover: the band and Hunter in workingman’s duds standing on a nondescript street corner.

When Warner Bros. boss Joe Smith first heard the finished record, he announced to all within earshot that, unbelievable as it might seem, the Dead had made a hit record. Smith was right. The album immediately took the Dead to a new level of popularity, and when they followed up Workingman’s Dead with the tonally similar and equally momentous American Beauty (“Ripple,” “Brokedown Palace,” “Sugar Magnolia,” “Truckin’ ”) just a few months later, they solidified their place among the great bands to survive the Sixties.

The Dead never stopped playing long, jamming tunes, even as they continued to carve out one slice of distinctive Americana after another through the early Seventies.

But Workingman’s Dead turned the Dead into a song band, and it was the launch pad for everything that came after it. It was a big gamble, a radical change in direction, but it paid off like a royal flush.