AC/DC's Cliff Williams reflects on four decades at the top of rock's bottom-end

The long-serving Aussie bassist dishes the dirt on Rock Or Bust

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

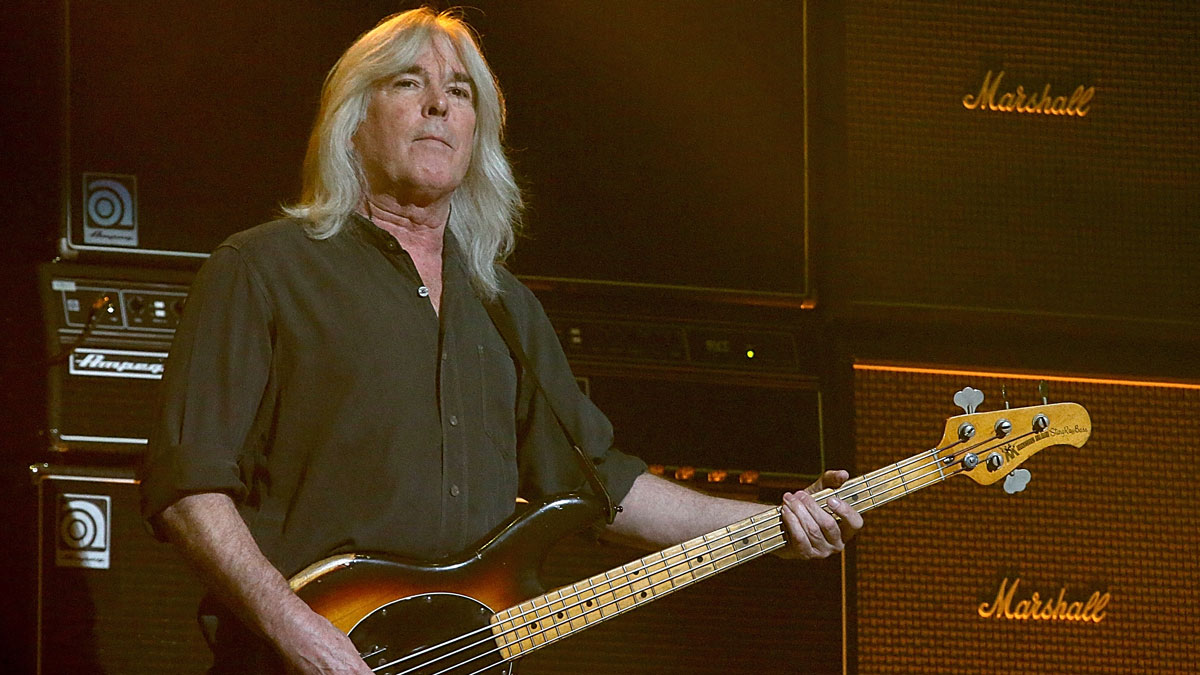

For a guy who’s been anchoring one of the biggest rock bands in the world for 37 years, Cliff Williams still manages to fly under many bass players’ radar. He is often dismissed as too simple or conservative to be considered among the greats, but his role in AC/DC provides quite possibly the loftiest example of what all rock bass players should aspire to.

Onstage, Williams cedes the spotlight to vocalist Brian Johnson and lead guitarist Angus Young, moving to the front only to when it’s time to sing his parts. His bass lines are refreshingly straightforward and to the point, never drawing too much attention, but always bolstering the song.

Because he fills this fundamental role so seamlessly, one might think that any bass player could do what he does. But there’s an art to his style: an abundance of subtleties, singular note choices, ideal note lengths, and deceptively simple but nasty grooves. AC/DC has been slamming audiences since the ’70s, and Cliff is a big reason this boogie train has rolled on so successfully for so long.

Late in 2014, AC/DC released Rock or Bust, its 12th album with Williams on bass, and 15th overall. The album was surrounded by controversy from the get-go. First, founding rhythm guitarist and primary songwriter Malcolm Young was diagnosed with dementia and had to retire from the band and the music business. He was replaced by his nephew, Stevie Young, for both the album and the tour.

Then, shortly after the album was released, drummer Phil Rudd got caught up in well-documented legal problems in New Zealand and was replaced by former Firm drummer Chris Slade. Both Stevie and Slade have played with AC/DC before, so the band was able to chug along.

Rock or Bust, produced by Brendan O’Brien (who also produced 2008’s Black Ice), is proof that AC/DC’s singular brand of rock & roll is as incendiary as ever. Williams throttles his now-signature eighth-note grooves with an arena-like authority that could only come from years and years of experience dominating the world’s biggest stages.

Songs like “Play Ball” and “Rock or Bust” are classic AC/DC anthems, while the grooves in “Got Some Rock & Roll Thunder” and “Emission Control” exude a downright sexiness— another essential component of the AC/DC sound generated by Williams and Rudd. Lots of folks predicted that Malcolm’s absence would spell the end of the band, but with brother Angus at the helm, it’s simply rock or bust.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

What’s the difference between playing with Chris Slade and Phil Rudd?

Obviously, they are two different players. Chris has a slightly different style of drumming. Phil could be described as a little looser, but Chris does a fine job. It doesn’t affect how I play; I just do what I do, and it fits in fine with Chris.

What impact did Malcolm’s absence have on the writing and recording process?

Angus had all of the material together prior to us getting anywhere near the studio. A lot of the ideas that he drew from were riffs he and Malcolm had. They have reels and reels of tapes of ideas from over the years that they haven’t touched.

Everything was pretty well together by the time we got to the studio. And Stevie had been spending time with Angus before we got together as a unit, so that sped up the process. Personality-wise, Stevie is very similar to Malcolm, and that spills into his playing, as well—he plays just like Malcolm. So that side of it was no different. It’s as solid as it was with Malcolm.

Stevie has played with you before, too.

It was a similar setup in the ’80s; Malcolm was out and Phil was out. Stevie was in and then, at that time, we had a fellow by the name of Simon Wright on drums. So, we’ve had this kind of scenario before.

Did you get material to work on before going into the studio?

No. We just showed up. This is our second go-around with Brendan O’Brien, in the same studio in Vancouver where we did the Black Ice album.

We like working with Brendan; he’s a musician first and foremost. He’s got great ears and knows how to put songs together. We’ve got a lot of respect for him. And with respect to many other producers, he’s not just a guy who directs his guys to twiddle knobs. He’s very hands-on—it makes a difference for us. We were in every day of the week, and he kept it rolling by keeping everyone involved all of the time.

Consequently, the bed tracks for this album were done, for the most part, in a month, which is fantastic because it’s fresh. We’ve had situations where we’ve gone in the studio and it took months and months and we just ended up playing the thing into the ground. So, it was a good fresh go-around. We’re proud of it.

Your playing really stands out. “Got Some Rock & Roll Thunder,” in particular, has an almost Andy Fraser-like vibe to it.

I don’t take too much credit for that. Ang played on the demo for that song and played bass all over it. Brendan got hold of the song and chopped together the bass line out of all the bits Angus played. I just put my stink on it and played it the best I could.

You seem to have an innate ability to outline the guitar riff but not follow it exactly, leaving more space.

It just happens; I just do what feels right to me. It’s also something that has developed over a long period of time playing with these guys—I just listen and play with the others, really.

You use flatwound strings in the studio. What about live?

For decades, I’ve used flatwounds everywhere— studio and live. I prefer the punch and the fatness of a flatwound string. I played wires when I was younger, but they have too much clatter for what I want.

Are you still playing StingRay basses?

Yeah. They’re really good workhorses, and I just love them. The ones I use are all from the ’70s. They just seem to fit the bill. Funnily enough, I’ve got five on the road with me, which I don’t need [laughs]. They’re all sunburst and they all sound pretty close, which is amazing.

Have you ever experimented with a different bass in AC/DC?

I played a Fender Precision for a little while, when I originally joined the band. Then—what is that little headless graphite bass that looks like a toothpick? Steinberger. Those were the first active pickups I ever used, and I really liked the sound, but I hated the bass.

I played it on the road for a while, but I just couldn’t stand the shape, so I pulled the guts out of it and dropped them into the P-Bass, which wasn’t bad. I’ve also fiddled around with a Fender Jazz over the years and a Gibson Thunderbird as well, but not for very long. I always seem to go back to the Music Man.

I’ve seen you play fingerstyle on occasion, but you’re mostly associated with a pick.

I very rarely play with my fingers anymore. Again, with the flatwounds, the pick gives me a really nice solid punch.

Downstrokes or a combination?

Mostly downstrokes until the hand feels like it’s going to fall off [laughs].

How did you first get into music?

Because of my father’s job, the family moved a lot. I was born in London, but we moved to Liverpool because the company that he worked for transferred him. I was about 11 then, and there was the whole Mersey sound going on. That was 1961. The Beatles and the Stones were just starting to pop up, and everyone in school wanted to be in a group, particularly in Liverpool, and I was just the same as the rest of them. So, I joined a little school band, started playing guitar for a while, and by then, there was an opening for a bass player, so I picked up the bass. I’ve pretty much done that ever since.

Who were some of your early influences?

Paul McCartney, and Pete Quaife from the Kinks. I listened to a lot of Stax and Tamla/Motown stuff, as well—not that I could play that. I was pretty much playing rock & roll and following all the ’60s rock bands that were running around in the day.

Many of our readers might not realize that you had a career with the bands Home and Bandit before joining AC/DC.

Laurie Wisefield and I started Home in 1967 in London. I left school and went back to London to try to do music full time. Laurie was with Wishbone Ash after that, and he’s played guitar with just about everybody under the sun as a session player since then. That lasted until the early ’70s. Bandit was a short-lived affair. I only ever did one album with that group.

I was intrigued by your playing on Home’s “Dreamer.” It’s so different from what we’re used to hearing in AC/DC.

It seemed to be the right thing for the song. It’s usually just a question of playing the best part for the song and playing it as good as possible—that’s about it, really.

How did you get the AC/DC gig?

I got a call from a guitar-player buddy of mine. My name had been put forward, and I was invited to audition, which I did. It was as simple as that.

Were you familiar with them?

I was. I’d seen them on Top of the Pops, on TV, and I’d heard about them. They had a good buzz going in London at the time.

What did you play?

The very first song we tried was a track called “Live Wire,” which, in fact, we opened the set with in those days. I was given some albums to learn after that first audition.

Were there any expectations or guidelines, or was it just like, be yourself?

No, I just played the way I do. There was another fellow, Colin Pattenden, who was Manfred Mann’s bass player, who they liked, as well. So I was fortunate that they chose me.

The first AC/DC record you did was Powerage, but original bassist Mark Evans claims he played on some of that record. In The Youngs: The Brothers Who Built AC/DC, Jesse Fink claims that producer George Young played on some of it.

Not at all, and Mark was long gone at that point. The Australian embassy in London was crapping me around something cruel. I had an interview, I would go along, and they would put me off.

This happened four or five times, and the guys were already in the studio in Australia. I said to the guy behind the embassy desk, “Look, I’m going to lose this job.” He said, “Well, I don’t see why an Australian shouldn’t have it anyway.” They just wanted to be bastards. I finally got my visa, it was all good, and we did the album.

Besides Brendan O’Brien, you’ve worked with other producers, including Mutt Lange and Rick Rubin. What do they bring to a band that already has such an established, identifiable sound?

The guys had success with the first AC/DC albums in Europe and Australia, but the band had never really been to America.

The first album we did with Mutt was Highway to Hell, and he was still young in his career at that time. He’s another guy with a great set of ears and a musical background. He was a bass player and singer in South Africa before moving into production.

We did two more albums with Mutt: Back in Black and For Those About to Rock. During that time, he was working with a lot of other bands, like Def Leppard, and he was starting to develop his sound.

I think part of the reason why Mal and Angus decided to move on from Mutt is he did have a signature sound that was becoming more prevalent than the band’s sound. It was getting that way. But we had tremendous success with him.

Speaking of tremendous success, does the rock & roll lifestyle ever get old?

Playing doesn’t ever get old. Travel and hotel life gets old, but playing is what keeps us going.

Do you have any advice for our readers?

Just listen to who you’re playing with—listen to the others. Too often, it seems younger players are just blasting away on their own. Be part of a unit and listen to your other players and what’s going on around you. And persistence is a wonderful thing.