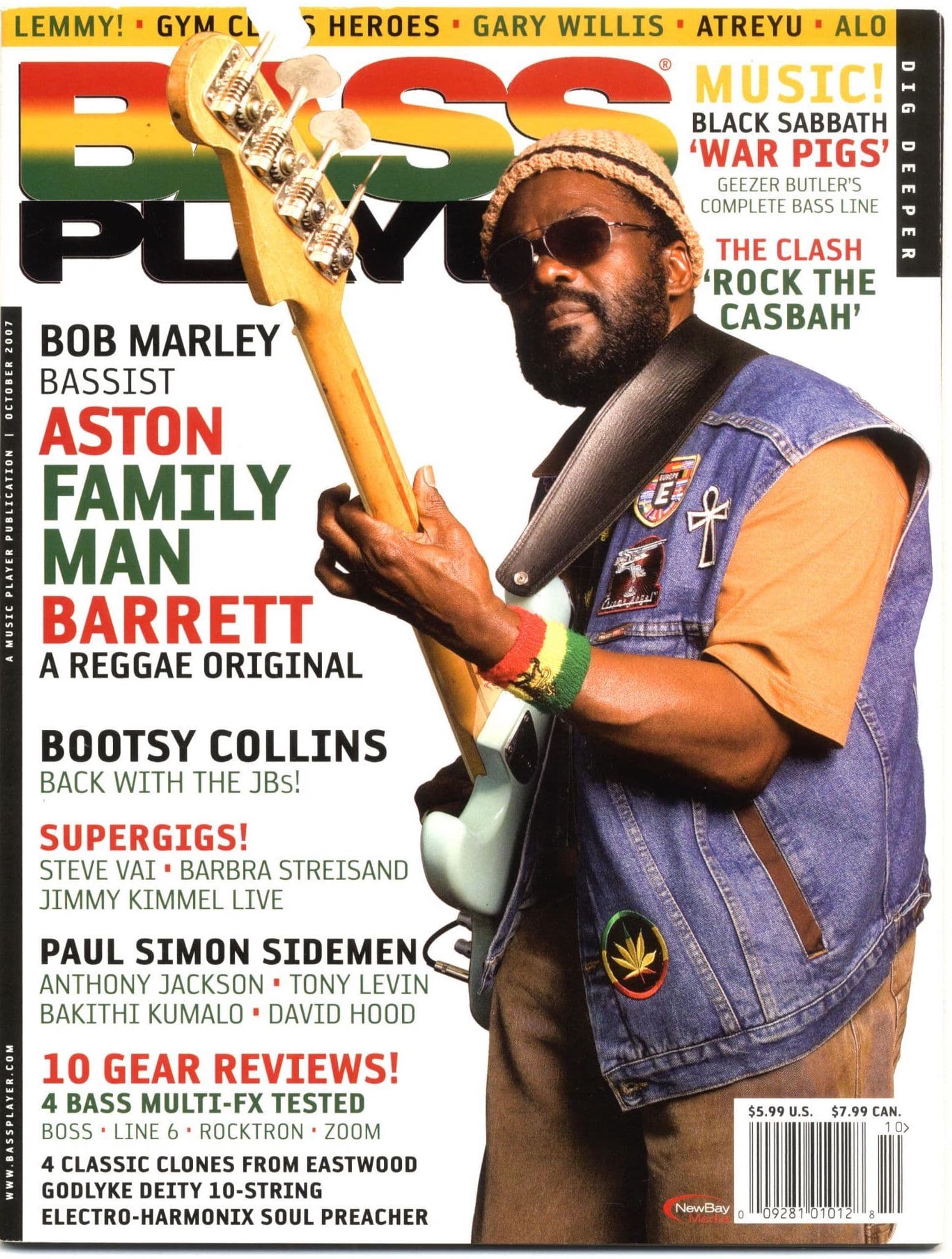

“Reggae carries that heavy message of roots, culture, and reality. So the bass has to be heavy and the drums have to be steady”: An interview with Aston “Family Man” Barrett

How Aston “Family Man” Barrett brought reggae bass playing to the world with Bob Marley & The Wailers

“I call it the earth sound,” chuckles Aston “Family Man” Barrett warmly as he describes what drew him to the bass all those years ago. Back then he was a young bike mechanic and welder scratching out a living in Kingston, Jamaica.

“Lloyd Brevett was one of my favorite bass players from Jamaica, and he played upright bass. I always tried to grab that sound, even when I am playing the electric bass. I decided to find out what key the earth tunes into. After a while, I realized the whole planet is tuned to Eb,” laughs Barrett. “When you play in that key, it makes you come to the center of the fretboard — you get a nice feel there, for sure.”

Even Barrett’s voice resonates with an earthen timbre. His smooth baritone sounds just as round and full, one can imagine, as the vintage Fender Jazz he first plugged in with Bob Marley & the Wailers in 1971, right at the moment when Jamaican reggae was poised to go outernational.

Marley gradually became the undisputed king — the scion of the Lion of Judah, as his loyal Rastafarian brethren might describe him — of the reggae style, swagger, and mentality. Meanwhile Family Man, along with his brother Carlton “Carly” Barrett on drums, helped to shape the Wailers’ modern sound. With an easy-handed and uncannily melodic approach to the instrument that reflects his love of upright bass as well as his ear for vocal harmonies, Family Man embodies the spirit and personality of reggae bass, as well as its staying power.

“I’ve been on the road from 1969,” Barrett observes almost matter-of-factly. When I spoke to him in 2007, Family Man was in the middle of yet another tour with the latest incarnation of the Wailers — a band that has continued to perform through all manner of adversity, including Marley’s death from cancer in 1981 and Carly Barrett’s murder in 1987.

“I’ve played before Bob, with Bob, and after Bob,” he says, “and along the way I create a whole new concept of bass playing. That’s just my thing. That’s my destiny.”

That destiny has its roots in Jamaica’s ska and rocksteady era—a time, in the mid 1960s, when the Supersonics’ Jackie Jackson, the Skatalites’ Lloyd Brevett, and the Heptones’ Leroy Sibbles were among the island’s bass rulers. Even so, for Family Man (a nickname he chose for himself as a youngster to signify his intent to “keep everyone in the band together”), the bass was not necessarily his first point of entry into becoming a musician.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I loved singing,” he says, citing the classic soul of James Brown, Stevie Wonder, and Curtis Mayfield that drifted over from the U.S. to Jamaican radio, “but I never practiced to be a professional when it came to my vocals. When I’m playing the bass, it’s like I’m singing. I compose a melodic line and see myself like I’m singing baritone.

“And when I decide to listen deep into the music — to all the different sections and instruments playing — I realized that the bass is the backbone, and the drum is the heartbeat of the music. So in our early years, my younger brother Carlton took onto himself the drums, and I took on the bass and decided I’m gonna construct it much better the other way. So first I made my own bass.”

It wasn’t as if Fams had a choice. Musical instruments weren’t cheap or easy to come by in the hardscrabble streets of Kingston. Like so many others with a creative urge, but without the materials to express it, the two brothers relied on their ingenuity: Family Man fashioned a makeshift upright bass out of a length of 2-by-4, a cut piece of plywood, and a curtain rod (with an old wooden ashtray for the bridge), while Carly built a drum kit out of different-size paint tins.

“We begin to practice drum and bass,” Family Man remembers, “what we call dub. When I rest my bass on the floor, I get that bass effect—boom, boom, boom, you know? That’s where I begin to create a new concept of time and melody.” They didn’t know it then, but the Barrett brothers were on their way to becoming one of the premier rhythm sections in reggae history.

When Family Man finally got his hands on a Hofner 500/1 “Beatle” bass, he and his brother formed their first band, the Hippy Boys, with singer Max Romeo. It wasn’t long before other groups and producers came calling. Fams’ very first recording as a session bassist was for one of Bunny “Striker” Lee’s groups, the Uniques, on a song called Watch This Sound – a cover of Buffalo Springfield’s For What It’s Worth, which had been a hit the year before in 1967.

With a sinewy, infectious bass line that seemed to leap out of the mix, the song attracted the attention of an up-and-coming producer named Lee “Scratch” Perry.

“Lee Perry get a hold of me by hearing of my new concept of bass playing,” Family Man says proudly. “He was turning into a record producer, leaving from the old stable of Coxsone Dodd at Studio One. The first thing we actually did together was the drum-and-bass track called Clint Eastwood, and that’s where dub was born. It was the first dub release not only in Jamaica but globally.”

The “new concept” that had attracted Perry’s attention was essentially the earliest example of a true reggae bass style — a melodic line that was locked into the downbeat. “I was improvising from the rocksteady feel,” Fams explains, “with a little tempo from the rocksteady and slowing it down from the ska — so the rhythm is in between the lines.”

As for what became known as the “dub style,” the echo-drenched, almost psychedelic mode of mixing invented by Perry and fellow producer King Tubby, it wouldn’t emerge until 1972 — but Clint Eastwood is notable for Perry’s reverberating vocal intro and a stripped-down melodic arrangement driven entirely by the bass, much as later dub mixes would be. The track cemented the Barrett brothers’ relationship with Perry, who made them a permanent part of his house band, the Upsetters. In late 1969, he took the Upsetters and another group, the Pioneers, with him for a tour of England. It was Family Man’s first time outside his native digs and into the spotlight.

By this time, a local singer who was looking to update his sound turned up on Perry’s doorstep. “When Bob [Marley] and Scratch meet,” he says, “I would say it was a mental, spiritual, and physical connection. And the first track we do with the Wailers— with Bob, Bunny [Livingston], Peter [Tosh], and the Upsetters — was called My Cup. It was the first time the Wailers get a real updated rhythm. It highlight them differently when everybody hear that beat.”

Again, the bass leaps out of the mix on My Cup, with Fams playing a buoyant, two-fingered stroke in the higher registers that offers a steady, insistent counterpoint to Marley’s soaring lead vocal. The chemistry between the Upsetters and the Wailers was so immediate, in fact, that the Barrett brothers decided to leave Perry’s stable and join the Wailers full time — a turn of events that rankled Perry for years afterward.

The move, of course, proved to be life-changing. The Wailers were soon signed by Chris Blackwell to Island Records, and in late 1972 they began recording Catch a Fire, quickly followed in mid-1973 by Burnin’. In fall ’73, the Wailers embarked on an American tour that paired them for nearly 20 dates with Sly & the Family Stone (earlier that summer, they had opened for Bruce Springsteen on a four-night stand at Max’s Kansas City club in New York) — but they were dropped from the bill after four shows because, according to former Island PR head Rob Partridge, they were blowing Sly off the stage.

“That year was our first time in the United States performing,” Fams recalls, “and the Family Stone had that rock groove style. It was a thriller.”

One performance from this period captures how inspiring the Wailers were as a live unit. Recorded in 1973 on Halloween night for a small audience at the Record Plant in Sausalito, California, the music on Talking Blues [Island, 1991] features supremely funky versions of Get Up, Stand Up, Slave Driver, Kinky Reggae, and Burnin’ and Lootin’ — the latter a death-dealing skank that mirrors Marley’s urgency by pushing the tempo to the breaking point. Throughout the set, Family Man lopes ahead, within and behind the beat, always conscious of what meshes with the song’s mood.

A clash of wills emerged among the three Wailers singers. By the end of the band’s first American tour, Bunny Livingston had quit; he was soon followed by Peter Tosh, prompting Marley to wonder aloud to Family Man what the group’s future would be. “Bob said to me, ‘What are we gonna do now? There’s only three of us left.’ And I said, ‘That’s the power of the trinity.’”

The year was 1974, and Marley and the Barrett brothers, according to Fams, solidified their working relationship in the form of a contract before heading again into the studio — this time to record Natty Dread. Almost immediately, Family Man began applying new discoveries he’d made about folding his bass into the fabric — the message — of the song.

“The message and the music come together,” he insists. “It’s all in the expression. We have this mission to accomplish, and we know thy will must be done by all means. So when we sing a song like Revolution — well, that’s a commanding, militant sound [sings the bass line]. You have to be as commanding as the lyrics, to let the lyrics stand out in the crowd.”

By this time, Family Man had fully committed to the Fender Jazz Bass (and sometimes a Precision, as seen in the photos that accompany the original Natty Dread LP); later he’d even remark with approval on how the Jazz was the preferred bass of Jaco Pastorius.

“I was using Acoustic amplifiers with the Fender. I had two 18” cabinets and two 4x15 cabinets. You need them that big to get that sound, because reggae music is the heartbeat of the people. It’s the universal language what carry that heavy message of roots, culture, and reality. So the bass have to be heavy and the drums have to be steady.”

Throughout the ’70s until Marley’s last sessions and live shows in late 1980, Family Man’s warm, full-bodied tone became a signature part of the Wailers sound. He would normally plug in with his tone controls set flat and the amps set at low gain; with the large cabinets he used onstage, his approach to bass was more about asserting a deep, low-frequency presence rather than in-your-face volume.

“In the studio,” Fams explains, “sometimes we used more of a miked bass to get the real rhythm and the tone, and sometimes we used a DI. I listen to the drumbeat, and I listen to where the singer’s melody was going, and I take it from there. I use both my thumb and my two fingers — it depend on the track and the feel of the rhythm. In the early years, I used my thumb most of the time.”

Of course, locked-up grooves came naturally to the Barrett brothers. An enduring example is the classic Marley anthem Exodus, which throbs along on a deceptively simple two-finger riff that swings hard with subtle grace-notes and accents — yet another facet of Family Man’s grasp of the bass from a singer’s perspective.

“The bass is pushing, like the way Bob sings, ‘Movement of Jah people.’ It’s a very commanding pattern — exactly like you say, hypnotic. And I play in about two or three different style [variations] within that one concept.”

Another highlight is Natural Mystic — the opening track on Exodus — which offers a vintage taste of the “one-drop” style that the Barretts helped invent (beginning with Duppy Conqueror in 1970). “Most of the beats were like an upbeat,” Fams explains, “so we decide to come on the downbeat, and feel it on the one-drop [where the bass drops out on a bar’s downbeat], which is the heartbeat of the people—the reggae music. It’s a feel within the Jamaican concept of calypso, niyabinghi, kumina, samba, and soca, with soul and funk inside. Reggae music has all of those.”

As basses go, the Hofner “Beatle” bass is not a widely recognized part of reggae’s roots — that spot being reserved primarily for the Fender Jazz and Precision Basses — but it did figure prominently in Family Man Barrett’s early years, as well as those of another bass prodigy out of Jamaica. “I gave Robbie Shakespeare his first Hofner bass,” Fams recalls. “That was the one I had, and when I give it to him, I tell him that when I’m out of Jamaica on the road with Bob and the Wailers, he must dominate the place with bass. And he did.”

Robbie himself remembers the exchange, as well as the importance of Barrett’s mentoring influence. “That’s who I get my teaching from,” he says. “Family Man, him say, ‘This the original bass Paul McCartney used to play.’ But the neck on it would bend, so it kind of hard to stay in tune, and the strings were pretty high off it. Over the years, if I play a regular bass, it would feel funny because I get used to that big bow [laughs]. But I had it for a long time because I love the sound. It just have a bass and treble [control] — my bass was always on and the treble always off.”

Shakespeare thinks he might have played the Hofner on the Wailers’ Concrete Jungle — one of the only tracks, over the course of eight years and nine studio albums, that didn’t feature Family Man on bass (although he did record a version, which is included on Island’s 2001 deluxe edition of Catch a Fire).

“After I bring up Robbie as a bass player,” Fams explains, “I take him on sessions with me every time. I wanted to keep him away from the hot-stepper business. I didn’t want him to walk on the wild side [laughs]. When you’re young, there’s a lot of things to take you away. So I take him on the session and I tell Bob, this is the bass player I’m bringing up, and he’s good—let him play. And him play on some for Bunny and some for Peter, too. He was the first bass player for Peter Tosh’s band.”

In fact, when Shakespeare joined Peter Tosh and Word, Sound & Power, the Hofner was his main bass—he can be seen playing it in the photos that accompany Equal Rights [Columbia, 1977]. “Peter was supposed to go on tour for Legalize It,” Robbie recalls, “and we—Sly [Dunbar] and I—asked him to come out and see us, and we hooked up from there.”

In 2012, Aston "Family Man" Barrett received a Lifetime Achievement award from Bass Player. He retired in 2019. This interview originally appeared in the October 2007 edition of Bass Player.

Based in New York City, Bill Murphy has contributed features, profiles and reviews to Rolling Stone, Time Out New York, Guitar World, Guitar Player, Bass Player, The Wire, Relix magazine and many more. He has also written liner notes for numerous album releases, including the lead essay for the Grammy-nominated Wingless Angels box set, produced by Keith Richards. Read more by him here.